John Adams is feeling festive

What does a renowned, Harvard-educated, Pulitzer Prize-winning classical music composer say just after the standing-ovation world premiere of his new symphony at Walt Disney Concert Hall, performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic under the baton of its wildly celebrated new music director, Gustavo Dudamel?

“That was rockin’, wasn’t it?” says a beaming John Adams.

Yeah, that’s the way “we old boomers” talk, Los Angeles Philharmonic Assn. President Deborah Borda, 60, jokes of her longtime friend and colleague Adams, 62. It doesn’t seem to surprise her during a conversation at the gala party after the Oct. 8 premiere that Adams would use the phrase when talking about “City Noir,” a work inspired by Hollywood’s classic noir films of the 1940s and ‘50s.

Besides -- it was rockin’. The buzz at the Latin-themed post-premiere affair seemed to have less to do with the generously distributed “Pasión” cocktail created in honor of Dudamel’s first Disney Hall concert as Philharmonic music director -- an alarmingly sweet combo of rum, pineapple, coconut juice and grenadine -- than with the afterglow of the music.

The heady sensation made it clear that 28-year-old Dudamel isn’t the only new kid at the Phil: The other is Adams, in his inaugural season as the orchestra’s creative chair and curator of the Philharmonic’s first festival of Dudamel’s tenure: West Coast, Left Coast, a three-week event launching Saturday and exploring California music.

The multidisciplinary festival will feature composers and performers long associated with California’s classical music scene, including San Francisco’s Kronos Quartet, composer-musician Terry Riley and former L.A. Phil Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen, now the orchestra’s first conductor laureate; Salonen’s “L.A. Variations” will be on the program with “City Noir,” also conducted by Dudamel.

Also on the eclectic list are former Beach Boy Brian Wilson and “The Yellow Shark,” a contemporary composition by the late Frank Zappa that Adams will conduct and describes as “fiendishly difficult.” “Being the cantankerous person that he was, when he composed classical contemporary music, he made sure it was hard,” Adams says with obvious relish.

More stuff you might not expect: a “Night of the Beats,” blending jazz performance with poetry, and a symposium that includes Grateful Dead bass player Phil Lesh, film composer Thomas Newman and USC history professor and former California State Librarian Kevin Starr. Starr’s series of books on California history were a major inspiration for “City Noir.”

“He’s quite an Americanist,” says Starr of Adams. “John has a special ability, or developed ability, to hear the music of various American places. Look at his operas: ‘Dr. Atomic’ [about the first test of an atomic bomb in Los Alamos, N.M.]; ‘Nixon in China,’ with the breathtaking arrival of the plane onstage -- when Nixon gets out, he really gives us Nixon in the music. His music is abstract but not too abstract. Despite the incredibly intricate theory behind what he does, you can follow the story he’s telling you.”

Festival artists coming in from outside of the classical concert world seem to appreciate the opportunity Adams offers to work outside the walls of their commercial careers. Newman, whose film score credits include “Wall-E” and “American Beauty,” says his new piece, “It Got Dark,” commissioned by the Philharmonic and receiving its world premiere during the festival, uses as inspiration Newman’s 20-year collection of L.A.-area ephemera, postcards, photographs and the like.

“Many creative choices that you are making for a movie are determinations, because you are looking at an image that gives you so much information, and it really determines the tempo,” Newman says. “It’s obviously much less so in terms of a concert piece, because the ideas originate from me. It’s very exciting, in a very different way.”

Also during the festival, audiences will get another chance to hear “City Noir,” a jazz-influenced work that Times music critic Mark Swed called Adams’ “most demanding symphonic work.” Says Adams, “I wanted to write a piece that had a California sensibility to it. . . . We want to create a repertoire that speaks to our culture the way that Mahler’s repertoire speaks for living in Central Europe around the turn of the 20th century.”

‘Only in L.A.’

A few of days after the premiere, Adams offers a more detailed observation on the star-studded premiere concert via e-mail: “What a circus that was! . . . ‘City Noir’ felt right -- neither too long or too abbreviated. And my wife got to sit next to the very charming Tom Hanks and his very generous wife. Only in L.A.”

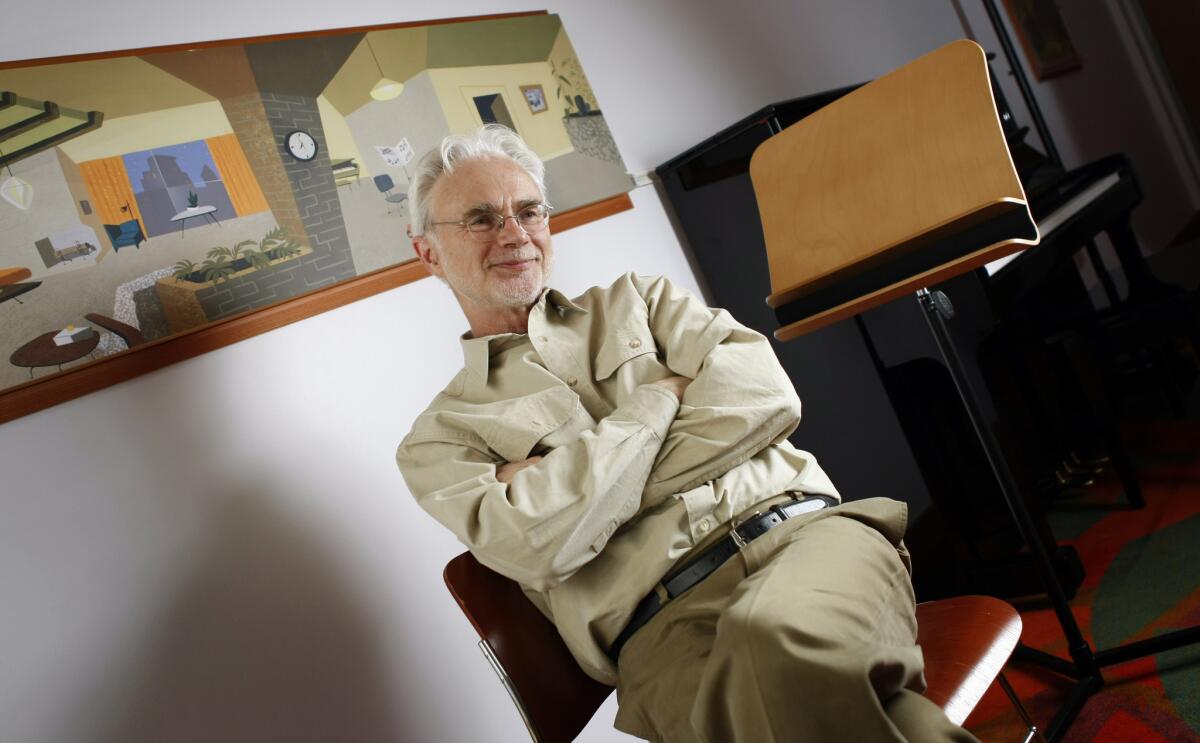

The white-haired “new kid” has a long history with the Phil: His “Dharma at Big Sur” was composed for the opening of Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2003, and Adams oversaw the Philharmonic’s Minimalist Jukebox festival in 2006.

Still, in a recent conversation with Adams -- a native New Englander who left and now lives and works in Berkeley -- the composer mirrors Dudamel’s boyishness as he talks about the festival and what “California music” means in 2009 -- although Adams’ boyishness is less Dudamel’s bouncy freshman than that of a popular college professor who still radiates the sort of youthful cool that makes students fight to sign up for his class.

Dudamel was not available for comment for this story but offered a few words on Adams to Andy Garcia for PBS’ “Great Performances” telecast of the gala concert. “For me, it’s an honor that John Adams wrote for my first concert with the orchestra,” Dudamel said. “I think he’s an amazing composer. He has Latin blood in his body.”

Adams’ 2008 autobiography, “Hallelujah Junction: Composing an American Life” -- named for his 2006 composition for two pianos and detailing his New England roots -- would not seem to concur with Dudamel’s blood-type analysis, but Adams has learned Spanish and traveled to Dudamel’s homeland when he was composing his 2006 opera “The Flowering Tree,” which involved Venezuelan artists; it was during that period that Adams became aware of Dudamel’s rising star. And Adams seems keen to absorb California’s multiethnic landscape, Latin and otherwise, into his music and his life.

“I feel very much like a Californian now,” says Adams, who was born in Worcester, Mass. “I grew up where everyone looked like me. . . . I don’t like looking around and seeing people of just one race or color.”

Even though the conversation took place on the stress-filled day before the “City Noir” premiere, Adams seemed eager to pause to reflect about “City Noir,” Dudamel, the festival and what it means to be a “creative chair.”

“I think they certainly could have a successful contemporary music program here without me, with or without a creative chair,” Adams says. “I’m not a conductor, although I do conduct -- but I’m basically a creative person, and this will be a chance to have a creative person as part of the extended Philharmonic family.”

He added that Dudamel, phenom that he is, can’t help being 28 -- or being new to Los Angeles. “Gustavo’s repertoire up to now has been largely the classics, and having not spent as much time in the United States and Europe, he’s not as plugged in as, say, Esa-Pekka Salonen. . . . We get along very well, I think he has a nice comfort quotient with me. His English is getting better than my Spanish.”

The Finnish Salonen, 51, who became music director of the Philharmonic at age 34, remembers what it was like to be the arriving wunderkind in a new place and thinks Adams is the perfect mentor to walk Dudamel through the process.

“It’s absolutely essential, of course, to have somebody to walk you through the various layers of historic sediment and the kind of cultural code that is so very different in different places,” says Salonen, whose own mentors include Steven Stucky, the Philharmonic’s longtime consulting composer for new music, and stage director Peter Sellars.

And a festival of California music? “The idea has been on the horizon for a long time, but I also think it makes perfect sense that it happens now during Gustavo’s first year, for him to establish himself in California,” Salonen adds. “It’s a great idea, and great timing.”

Like Borda, Salonen appreciates that Adams’ interests come from many spheres outside music. “There is an intense curiosity about him that I find very inspiring,” Salonen says.

Grant Gershon, director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale, is also a longtime associate of Adams and recently conducted the chorale in a performance of choruses from Adams’ controversial opera “The Death of Klinghoffer.” Gershon believes that Adams is the perfect composer to curate West Coast, Left Coast because he is so, well, not like a composer.

“He’s an extremely good listener, which is an unusual trait for a composer,” Gershon says. “He clearly enjoys human interaction. All composers have to be very attuned to the music in their heads; it’s hard to open up their ears to what’s happening outside. He’s genuinely interested in hearing other viewpoints and in real conversation.”

These days, Adams is taking a breather from composing, is lecturing and writing and has launched a new conversation with the public through his blog Hell Mouth, which can be found on his website www.earbox.com. A recent post: “Surviving a first rehearsal.”

Says Adams of West Coast, Left Coast: “It’s definitely a speculative experiment. The first festival I curated here, the Minimalist Jukebox, was more successful than anyone dreamed it was going to be, but there I had the ability to choose music from all over the world in a certain stylistic proclivity. The West Coast is not famous for having produced a great canonical body of classical pieces the way that France or Germany or, for that matter, New York has.

“But there are some interesting works that I do think reflect life out here,” he adds.

Will they open a new conversation with Los Angeles? Replies Adams: “Ask me after the festival. . . . Whether California has developed its own uniqueness, its own ‘flavor’ to constitute a truly identifiable style in music, literature, photography et cetera is still a question. Maybe we’ll be just a little bit more conscious of those questions after the West Coast, Left Coast festival has ended.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.