After 27 years in a warehouse, a once-censored mural rises in L.A.’s Union Station

Barbara Carrasco has waited 27 years for this moment. The artist stands in Union Station’s cavernous former ticket concourse and gazes up at her massive mural, “L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective,” as it’s being installed, her hazel eyes wet with emotion.

“This is amazing. My baby’s going up,” she says, one hand over her heart.

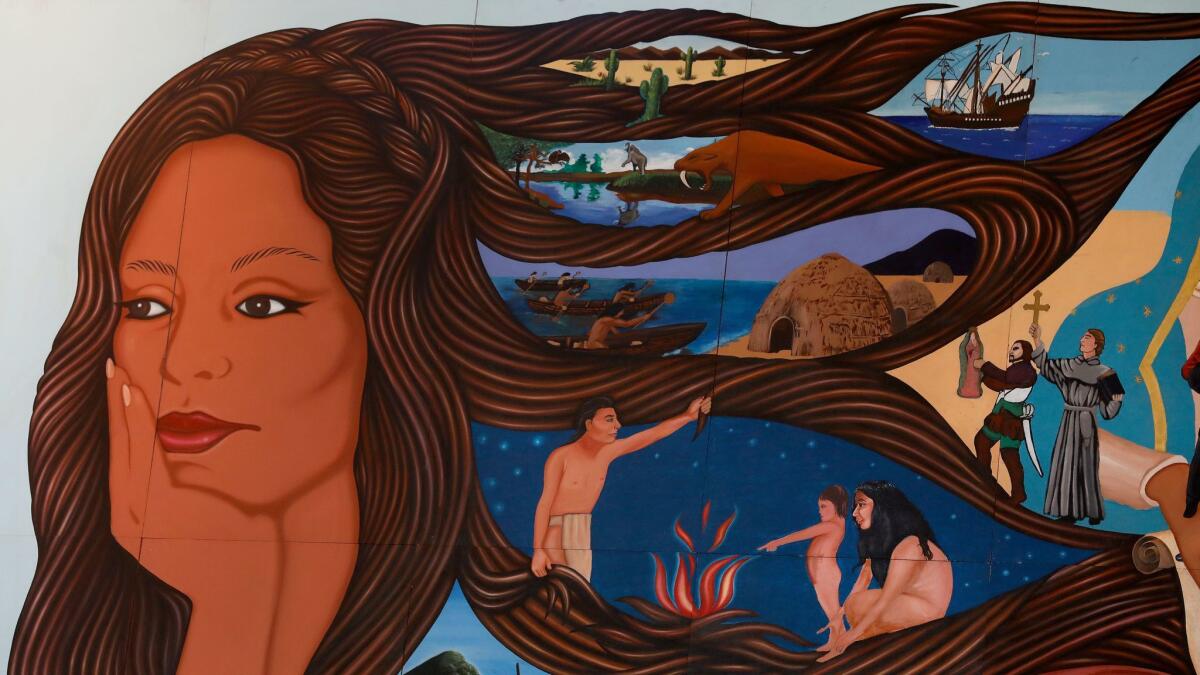

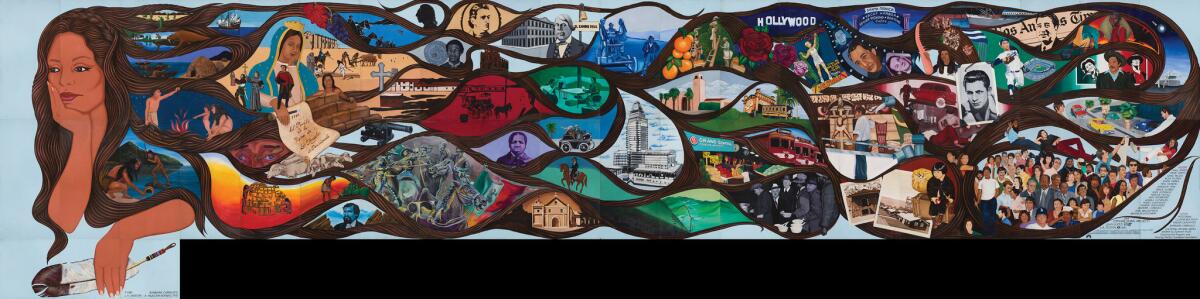

Carrasco painted the mural’s 43 panels — a chronological history of Los Angeles, from prehistoric times to the founding of the city in 1781 to the year she created the piece, 1981 — for Los Angeles’ bicentennial. She was a drafting artist for the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency, which commissioned the work. It was intended to hang on the exterior of a McDonald’s on Broadway in downtown L.A.

“I’m a Mexican, and I wanted to show a diverse reflection of Los Angeles,” Carrasco said. “This was my chance to show what I wish was in the history books.”

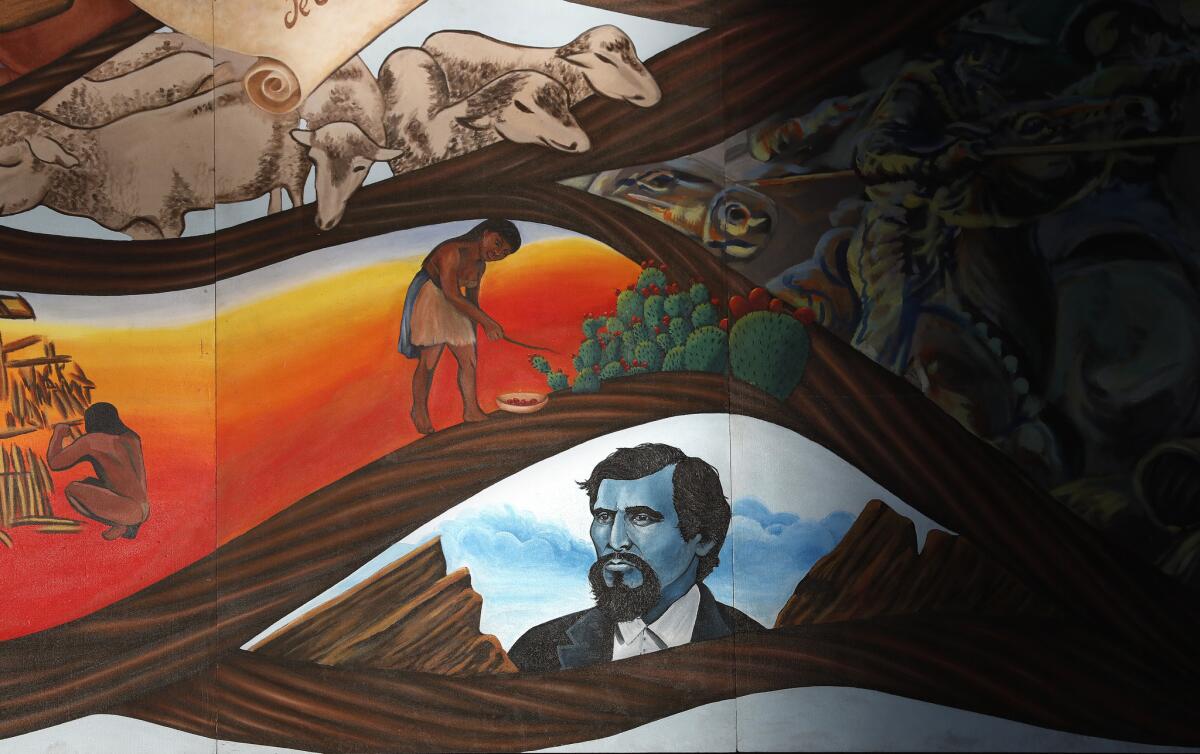

The city had approved Carrasco’s sketches of the mural, but while she was painting it, the agency asked her to remove 14 images from the work in progress. Although much of the imagery is pleasant, like the Hollywood sign and the construction of City Hall, other pictures depict ugly incidents experienced by communities of color. The CRA requested cuts of former African American slave-turned-entrepreneur and philanthropist Biddy Mason, the Japanese American internments during World War II and the 1943 Zoot Suit riots, in which Navy personnel attacked Mexican American youth.

Carrasco refused to paint over her work, and the mural project was canceled.

“They said, ‘Why do you wanna focus on negative images?’ ” said Carrasco, who had involved family members and other artists in the project as well as children from different neighborhoods who helped with the brushwork and also appear in the mural.

“I was very disappointed for everybody, all the artists who worked on it, the young people. It was unexpected. I got a little depressed over it, all this work and then nothing. It was a hold on my life, actually.”

Carrasco’s mural sat in storage for nearly a decade. In 1990, it was displayed for several weeks at Union Station — the only time the work had been shown in its entirety. When the exhibition was over, the work was packed up again and returned to storage, at Carrasco’s expense, in Pasadena.

The mural’s reinstallation at Union Station — an “un-censoring,” as it’s being called — is part of the exhibition “¡Murales Rebeldes! L.A. Chicana/o Murals Under Siege,” co-curated by LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes and the California Historical Society. It’s their offering for the Getty-led Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA.

The exhibition explores significant artists or collectives whose public murals were in some way censored, destroyed or neglected. (Featured artists include Willie Herrón III, Ernesto de la Loza, Alma López, Roberto Chavez, Sergio O’Cadiz Moctezuma, Yreina Cervántez and East Los Streetscapers.) Through documentary photographs and sketches, personal letters and city records, even concrete chunks of murals, the exhibition tells not only the stories of the art and the artists but also speaks to the assertion of — and reception to — Chicana/o identity in public art.

“Barbara’s mural is an amazing example of the themes of the show,” co-curator Jessica Hough said. “The broader issues around censorship are really important; and it speaks to the history of our entire city, but does so from a very specific and feminist perspective. [We wanted] to show that the kind of history being portrayed here, from the perspective of L.A.’s communities of color, is woven together, as it is visually in the piece, and that it matters.”

At a time when the veracity of the government is being called into question and historical monuments are being reconsidered, Carrasco’s mural is especially timely, co-curator Erin M. Curtis said.

“We’re at a moment when truth has become ever more subjective,” she said. “Historical narratives are being reframed. There’s an attempt to erase certain historical narratives — and it’s so important for us to have this kind of complete and inclusive history presented to the public.”

It’s needed more now, Carrasco said, than when she first painted the mural.

“It’s about preserving our history, our real history,” she said.

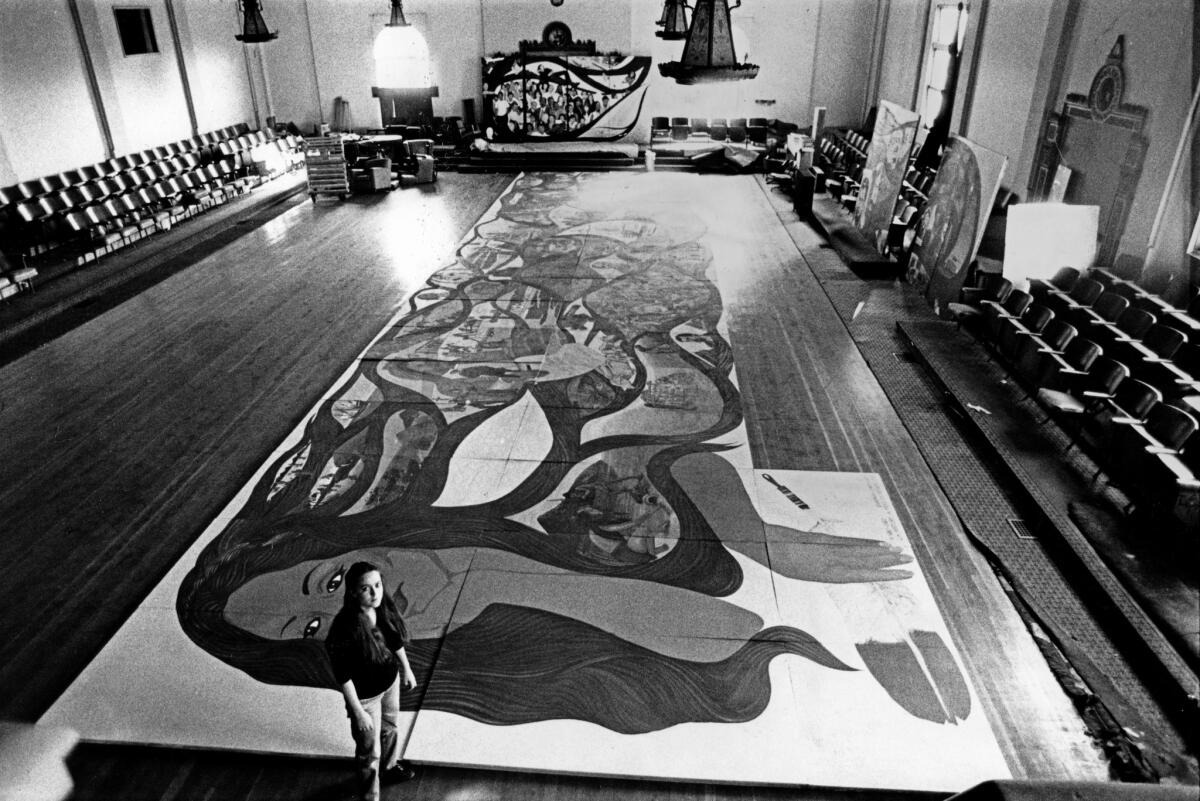

The installation of the mural is complicated. It can’t be hung directly on Union Station’s wall, as drilling into the historic building would damage it. Instead, the 43 panels, which are 8 feet tall and made of wood, are affixed to an armature structure that hangs from 30-foot-high scaffolding.

Carrasco watches crew members, who are scattered across the scaffolding, which spans nearly the length of the Union Station wall. Most of the panels are still wrapped in plastic and sit on carts, while others are laid out on the floor on packing blankets.

The artist hovers over some panels on the ground, taking in the imagery, while the sound of drilling cuts through the air. “Oh, my,” she said, smoothing her hair with her hand. “The colors are really preserved — as vibrant now as they were — because it was in the dark for so long.”

As she moves between the panels, Carrasco’s emotions swing between mellow nostalgia and childlike joy, with occasional bursts of maternal concern for the installation crew members, who balance themselves on wood planks 20 and 30 feet high.

“That looks so scary. I’m so scared for them,” she said.

Carrasco said she conducted months of research when first sketching the piece, poring over L.A. history books and speaking with historians as well as descendants of the Gabrielino-Tongva tribe. Painting the mural — first in her downtown Los Angeles studio, then on a vacant floor of City Hall East, where there was more space — took about eight months.

She leans over a panel depicting the construction of the San Gabriel Mission.

“That’s one of the kids who worked on the mural. He’s portrayed as one of the indigenous people. Yeah, that was fun putting him in there,” she said, before strolling to a panel representing the Mexican American War. “The Streetscapers painted it,” she said. “It’s their style, real loose.”

Then: “There she is, Biddy Mason!” She nods at the former slave’s face on the mural. “She’s an inspiration. She was a cool lady. She fought for her freedom.”

One panel depicts the 1932 painting — and the 1934 whitewashing — of David Alfaro Siqueiros’ famed Olvera Street mural, “América Tropical.”

“I’m a big fan of his,” Carrasco said. “And I thought it was important that a major Mexican muralist came to L.A. to do a mural, and the same thing — it was censored.”

The official unveiling of Carrasco’s mural was Friday, and the work will hang in Union Station through Oct. 22. Roundtable discussions and other public programs have been scheduled, and the “¡Murales Rebeldes!” curators have arranged for self-guided walking tours that will stop at three sites: Carrasco’s Union Station piece, the since-restored Siqueiros mural nearby and, finally, La Plaza, which has the exhibition.

Carrasco’s hope now is to find a permanent home for her mural. Union Station would be perfect, she says. “So many people come through here, and it’d be a welcoming kind of visual narrative of L.A. history.”

Carrasco’s eyes are still glassy with wonder as she stands in the concourse watching her work come to life, panel by panel.

“I’m 62. I just feel like it’s time to let go of it. So much blood sweat and tears went into this piece,” she said, noting again the collection of people who worked on the mural. “I just feel we were all let down when it went into storage. I’m just so happy now that people will have an opportunity to see it.”

You can find all of The Times’ feature articles and reviews on Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA at latimes.com/pst.

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

MORE ART NEWS AND REVIEWS:

A deeper look inside the “¡Murales Rebeldes!” book

'Radical Women' at the Hammer Museum is a startling show you need to see, maybe twice

Your invitation to dreamland awaits at Ad Minoliti's exhibition at Cherry and Martin gallery

The incomparable political art of Congolese choreographer Faustin Linyekula

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.