Modern dance pioneer Donald McKayle dies at 87

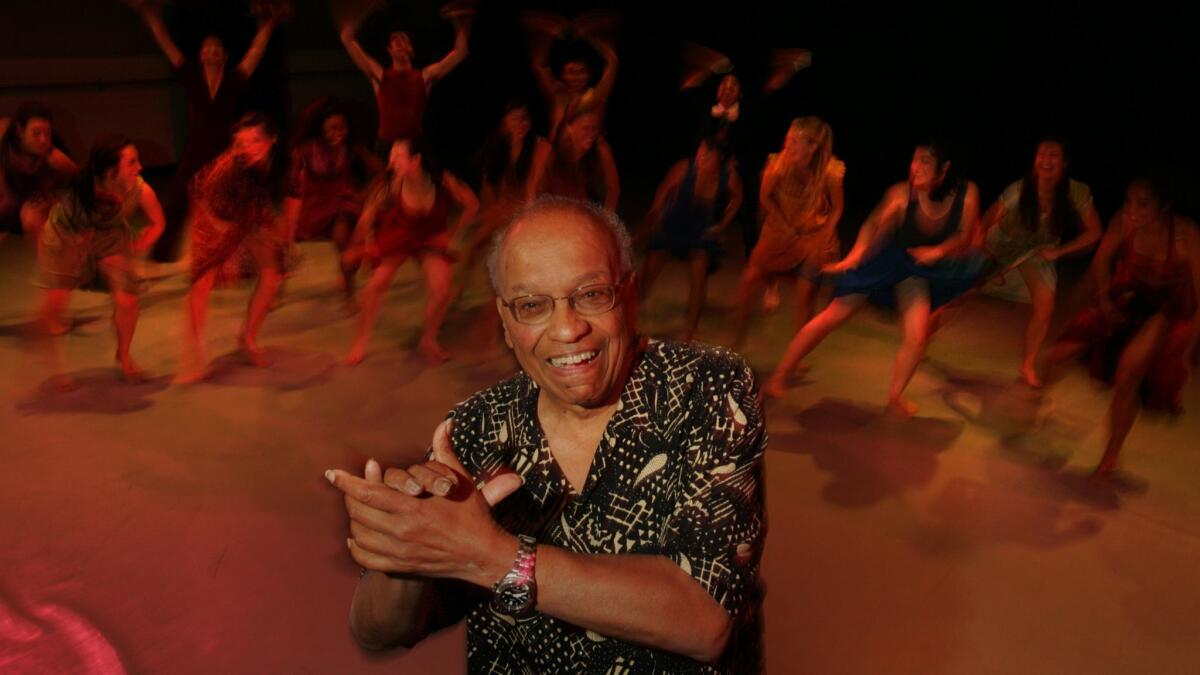

Donald McKayle, the pioneering dancer and choreographer whose seven decades in modern dance distinguished him as one of the art form’s leading lights and socially conscious practitioners, has died. He was 87.

He had complications due to pneumonia, his family said.

McKayle created hundreds of pieces for companies around the world, in addition to performing works by giants of choreography such as Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham. He was a five-time Tony Award nominee and one of the first African American men to both direct and choreograph major Broadway musicals, including “Raisin” (1973) and “Sophisticated Ladies” (1981).

In the 1950s and ’60s, he ran Donald McKayle and Company, a troupe whose distinguished alumni included Alvin Ailey, Eliot Feld, Lar Lubovitch and Arthur Mitchell. McKayle also choreographed for film and television and taught and administered dance programs across the country, including at Juilliard and UC Irvine. In 2000, the Dance Heritage Coalition and the Library of Congress named him to the list of “America's Irreplaceable Dance Treasures: The First 100.”

“He was an incredibly warm and thoughtful person with a truly original creativity,” said Stephen Barker, dean of UC Irvine’s Claire Trevor School of the Arts, where McKayle taught for nearly 30 years. “He was one of those people who was both a deeply trained dancer, and also a social commentator and social critic.”

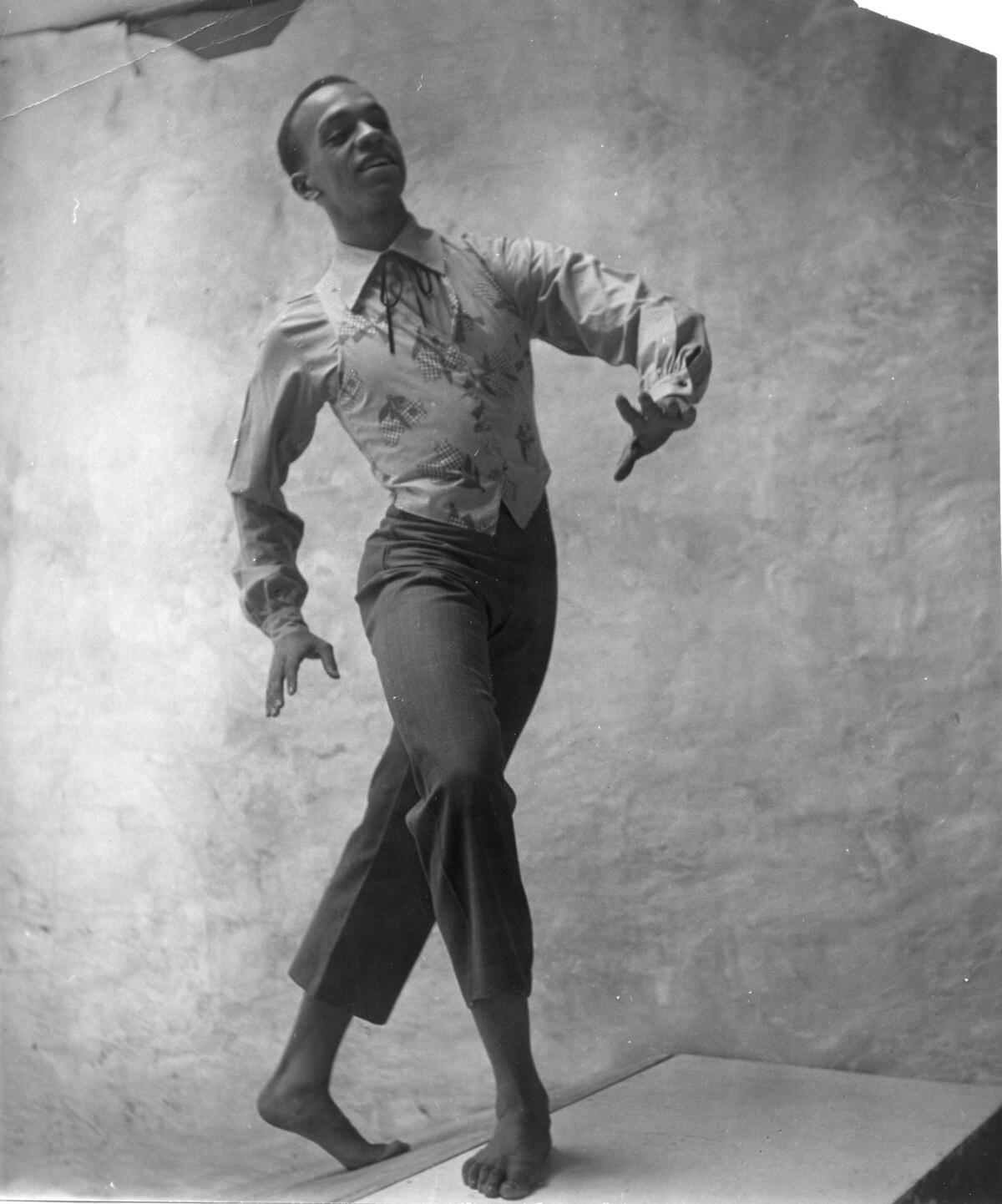

Standing a graceful 6 feet, 2 inches, McKayle was described by dance legend Carmen De Lavallade in a 1998 interview with The Times as having the “beauty of a big cat.” McKayle’s dances were known for their humanism as well as their eclectic mix of influences including tap, flamenco, folk and ballet, with an eye toward exploring distinctly African American themes.

“He created very important social work in terms of the racial divide,” his wife, Lea McKayle, said by phone from the couple’s home in Irvine. “His work was cutting to the heart, but not full of rage and anger.”

“Rainbow ’Round My Shoulder” (1959), which is among McKayle’s most celebrated pieces, is set to folk songs and chants from Southern chain gangs and plunges into the psyches of exhausted indentured laborers as they conjure a female muse who represents freedom and spiritual fulfillment. Another influential piece, “Games” (1951), uses children’s chanted songs and dialogue to present a tale of youthful street play interrupted by a police beating.

“He told stories from the personal perspective rather than the political perspective,” said his daughter Gabrielle McKayle, addressing her father’s reputation for leading with the heart and soul, and trusting that the mind will follow.

Donald McKayle was born in 1930 and grew up in Harlem. His father worked as a maintenance man at movie theaters and clubs, a job that afforded a young McKayle free access to the pop culture of the day. Those early influences stuck with him for life.

He became certain of dance as a career at age 15 after seeing the early modernist Pearl Primus perform. He got the opportunity to study with Primus two years later when he earned a scholarship to the New Dance Group, where his instructors included Graham, Cunningham and Anna Sokolow.

He premiered his first solo piece, “Saturday’s Child,” in 1948 at the age of 18, after which, by McKayle’s account, he was never out of work — a rarity in the fickle dance world.

His work was cutting to the heart, but not full of rage and anger.

— Lea McKayle, speaking of her late husband, Donald

His most notable movies are “Bedknobs and Broomsticks” (1971) and “The Great White Hope,” (1970) but the bulk of his screen work was done for TV. He created the choreography for the Oscars and the Grammys, as well as for network variety shows.

His first marriage to Esta Beck McKayle, one of the dancers in his company, ended in divorce after the couple had two children. In 1965 he married Lea Vivante, an Israeli flamenco dancer he met while working on a commission for Tel Aviv-based Batsheva Dance Company.

Daughter Gabrielle McKayle remembered her father as a busy man with a bottomless creativity. He had a beautiful voice and sang to the children constantly, she said. He loved to cook and made costumes for Lea’s dance performances. He once measured her in her sleep in order to finish a costume on time. Gabrielle remembered his keen eye for detail, applied to the miniature dolls he made for the Christmas tree every year out of pipe cleaners, cotton, crepe paper and paint.

“A flamenco dancer with crepe paper ruffles sewn onto each petticoat, and an Eskimo with fringed boots,” she said, describing the dolls. “A couple of times when he was out of town, he sent my sister and I books that he wrote … with stories about us, about what he imagined we were doing over the summer, and he painted them with watercolors.”

Donald McKayle’s career in academia included an appointment as dean of the CalArts dance department as well as artistic administrator of the Inner City Repertory Dance Company in Los Angeles. He served on the faculty at the Juilliard School, where he held an honorary doctor of fine arts degree, as well as at Bennington College, Sarah Lawrence and Bard College. He joined the faculty at UC Irvine in 1989, where he was a professor emeritus of dance and where he continued teaching until shortly before his death.

In 2001 McKayle published an autobiography, “Transcending Boundaries: My Dancing Life,” which was honored with the Society of Dance History Scholars’ de la Torre Bueno Prize. He was also the subject of a 2003 PBS documentary, “Heartbeats of a DanceMaker.” In 2005 he was honored by the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and presented with a medal as a master of African American choreography.

“I’m not a disciple who worships at one altar,” McKayle told The Times in 1998. “I have an ecumenical love for the field. I love differences and change.”

McKayle is survived by wife Lea, daughters Gabrielle and Liane McKayle, son Guy McKayle and two grandchildren.

MORE ARTS:

Kathleen Battle, Julia Bullock and the saga of opera singers of color

What does it mean to be of mixed race in America? A photographer shoots for an answer

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.