Column: Why it matters that AFI’s Lifetime Achievement Award is going to ‘Star Wars’ composer John Williams

Hearing that John Williams would be given the American Film Institute’s 44th Life Achievement Award, I needed convincing that this was news. Isn’t he already the most honored composer, at least during his lifetime, in history? And who in Hollywood, for that matter, can match his acclaim? Williams’ shelves sag with five Oscars (out of 50 nominations!), 22 Grammys (plus more than three dozen additional nominations) and BAFTAs, Golden Globes and Emmys.

What is news, however, is that this is the first time AFI’s honor — which has gone to such film greats as Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock and celebrities of the level of Elizabeth Taylor and Tom Hanks — is being given to a composer. I didn’t realize the full significance of that until this week when I watched “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” and realized just how threatened symphonic film scores have become.

MORE: Rank your favorite John Williams scores

This seventh in the “Star Wars” series has everything you would expect from Williams, whose music played an incalculable role in creating the “Star Wars” phenomenon from the start. Thanks to Gustavo Dudamel conducting the opening and closing credits in this latest “Star Wars” movie, Williams’ music has never sounded better. But in everything about the film, and especially the sound design, music doesn’t much matter anymore.

Except that it does matter. The punch that Dudamel gets out of the first chord, and the opening music, so familiar but sounding so grand, surely primed crowds in a way nothing visual ever could.

Creating a sense of expectation has always been what Williams does best. “Jaws,” for instance, would not have had the same bite without its portentous score announcing not the presence of the shark as a telltale narrative score might be expected to do, but the simultaneous fear and thrill of the shark. The music is what the film can’t show or tell.

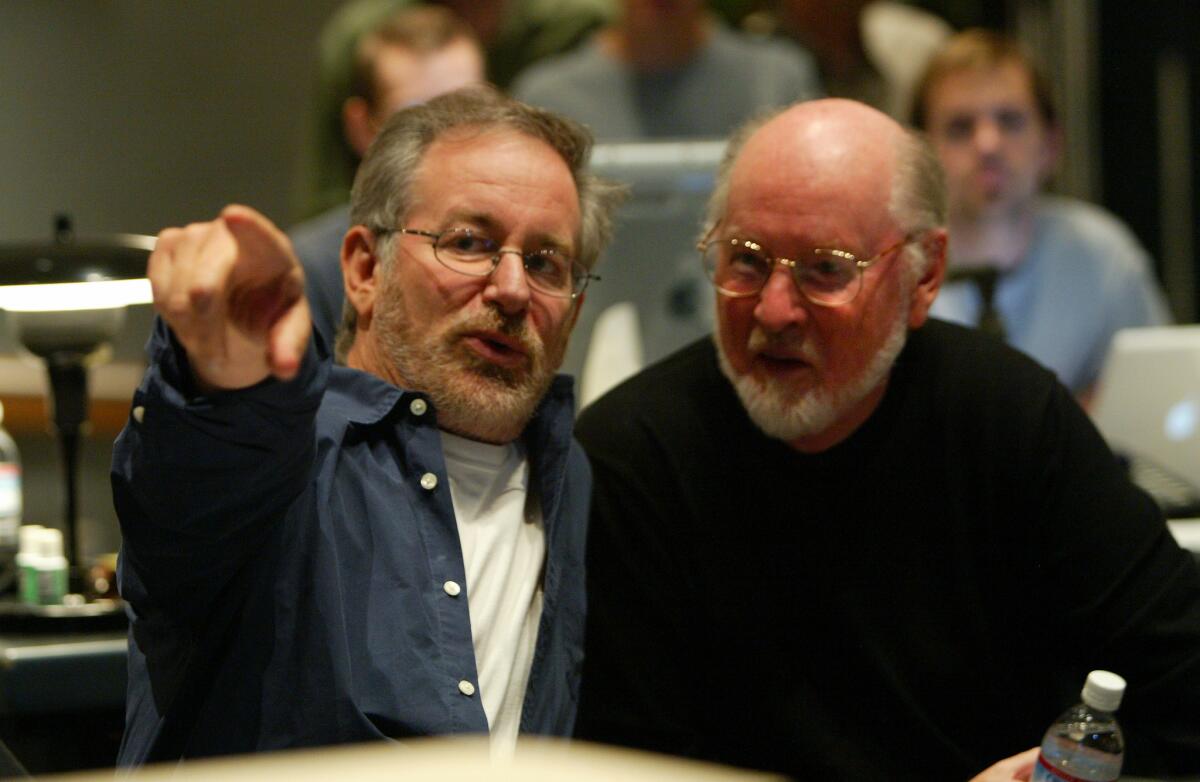

There is thus little question that without Williams’ music for “Jaws,” Steven Spielberg’s first hit would not have been so huge. From then on, picture after picture, the director’s storied career has been all but wedded to Williams’ music.

Same goes even more so for George Lucas. The original orchestral soundtrack from the first “Star Wars” film is said to be the highest-grossing recording of “nonpopular” music of all time.

“Nonpopular,” this music that has been heard in probably every corner of the globe? Dudamel grew up on it in Barquisimeto, Venezuela, and remains Williams’ greatest fan. But yes, nonpopular. The essence of Williams’ orchestral writing is symphonic. Classical music lovers have long enjoyed pointing out this and that source for Williams’ thematic ideas, such as a symphony by Erich Wolfgang Korngold that gave him some “Star Wars” material.

This is no more stealing than, say, Stravinsky, a famous musical theft, helping himself to Russian folk music while attempting to hide his tracks. Williams trusts music. That is the real power his scores have to offer.

I have found that when I like a movie Williams has scored, such as the original “Star Wars,” it is because of the music. When I don’t like a movie, say “Schindler’s List,” it is because I have a problem with the score. It boils down for each of us to our comfort level at emotional manipulation. The fact is, when Williams scores a film, the music is integral.

That is, until “Star Wars: The Force Awakens.” The orchestra is so artificially recorded as to sound as phony as CGI looks. It is so pummeled by generic sound effects — and the cheesiest electronic music I’ve heard in a long time — that the music has little to resonate one way or another. The only way to hear what Williams wrote is to listen to the soundtrack recording. The DVD and Blu-ray of the movie provide only a multichannel, orchestra-unfriendly mix (the two-channel mix has added “descriptive audio”).

Unlike most film scores these days, where the tedious closing credits are played out over a song you don’t feel like you need to stay for, Williams’ 10-minute symphonic movement is based on his “Star Wars” themes. If you do sit through it, you will see the names of hundreds of digital designers, of clerks and cashiers. But the only musicians I caught were Williams, conductor and orchestrator William Ross and Dudamel. The musicians are of less importance than assistants, apprentices, drivers or caterers.

Do the producers care? “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” broke box office records and made a couple of billion dollars. When it opened last year, the film became a pop culture moment (already barely remembered). But there would have been no “Star Wars” franchise without the first film, which had something far more lasting than a pop culture moment. What made it last was the music. Hollywood is not paying attention.

ALSO:

John Williams on 'Force Awakens' score: 'I felt a renewed energy, and a vitality'

'Star Wars' surprise: Gustavo Dudamel conducted parts of 'The Force Awakens' score

From the archives: John Williams and Steven Spielberg mark 40 years of collaboration

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.