And the winner actually is …

The final-act confusion over the best picture award that had movie moguls staggering out of the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood after Sunday’s Academy Awards was a fitting conclusion to a show that had been pulling off a more artful bait-and-switch all night.

The expectation was that Hollywood would slam President Trump as it had done throughout the awards season. The question on the minds of Oscar watchers going into the ceremony was who would be most likely to follow in Meryl Streep’s Golden Globes footsteps.

Would one of the acceptance speeches turn into a broadside? Would a presenter go rogue and exhort Americans to rise up and resist? Or would the political fervor be reserved for the stealth satire of host Jimmy Kimmel, who in his opening monologue joked that “this broadcast is being watched in 225 countries that now hate us.”

1/60

Presenter Warren Beatty and host Jimmy Kimmel try to explain to the audience how the wrong envelope for best picture was read on stage during the Academy Awards telecast on Feb. 26. In background are “Moonlight” writer/director Barry Jenkins, left and “La La Land” producer Jordan Horowitz embracing.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 2/60

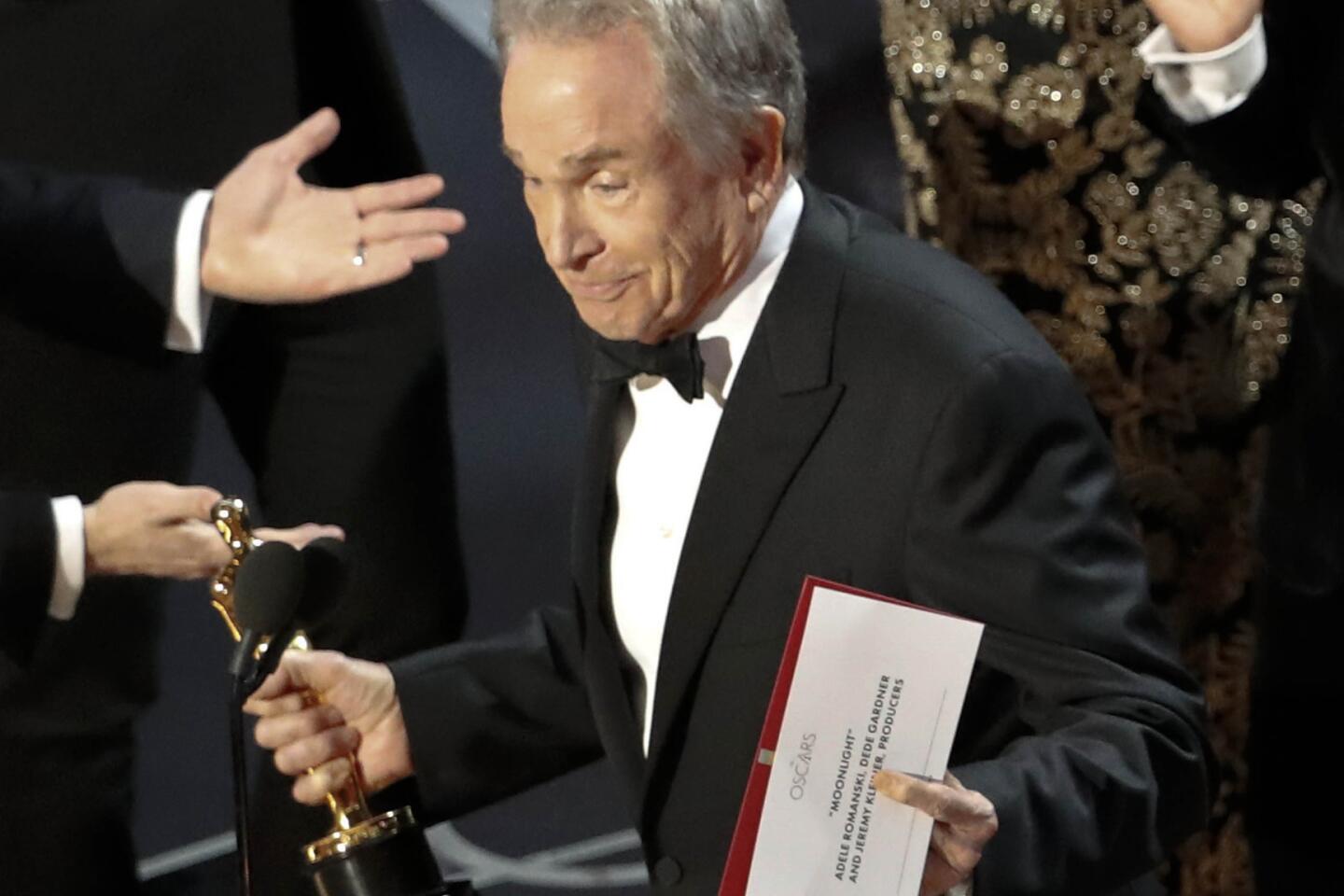

Presenter Warren Beatty tries to explain to the audience how the wrong envelope for best picture was read onstage during the Academy Awards telecast on Feb. 26.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 3/60

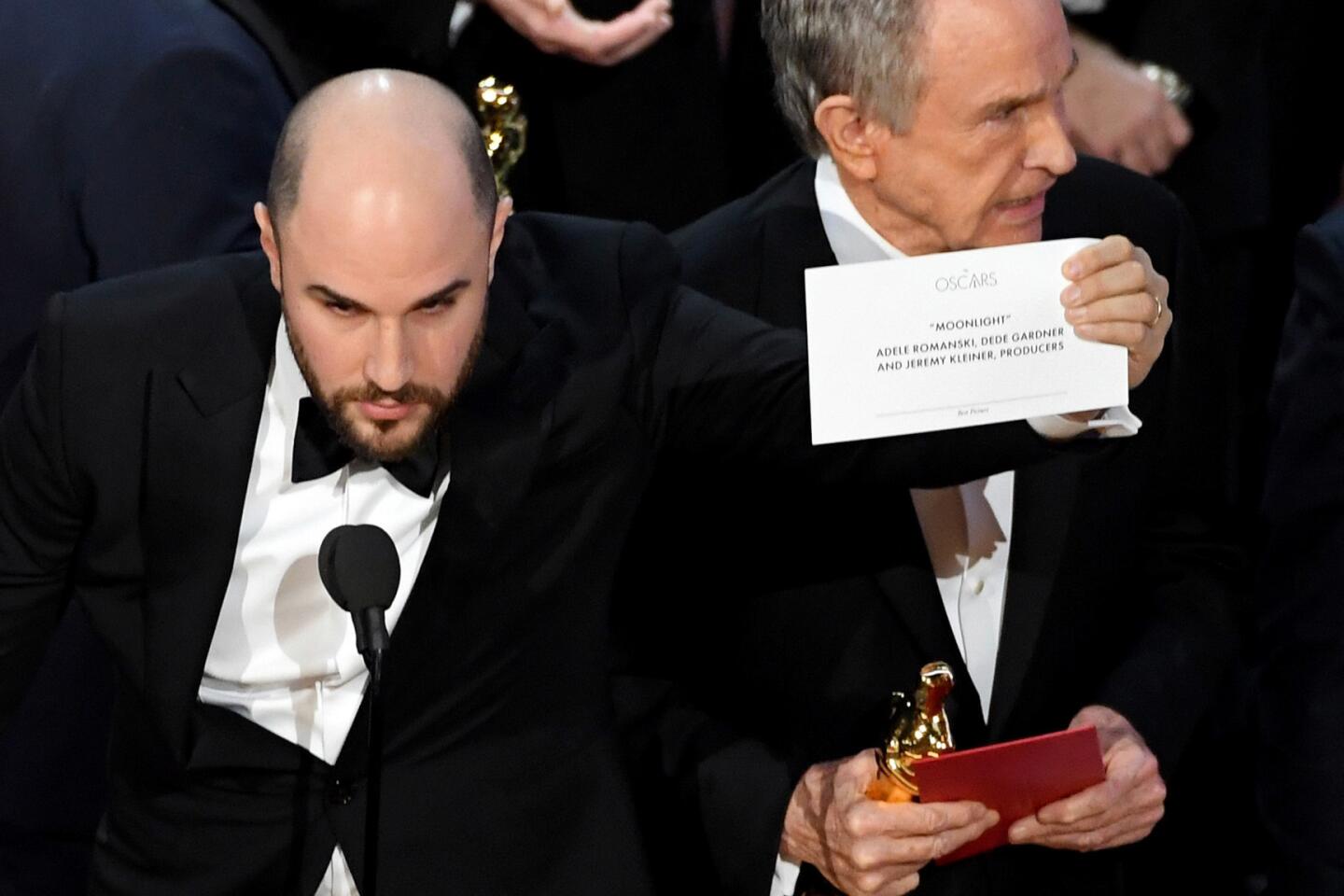

“La La Land” producer Jordan Horowitz holds up the winner card for best picture. His film had been read as the winner, but the actual winner was “Moonlight.”

(Kevin Winter / Getty Images) 4/60

The audience at the Dolby Theatre is stunned after the best picture award is mistakenly announced as “La La Land” instead of “Moonlight” during the 89th Academy Awards.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 5/60

Presenter Warren Beatty and host Jimmy Kimmel try to explain to the audience how the wrong envelope for best picture was read onstage during the Academy Awards telecast on Feb. 26. At right are “Moonlight” writer/director Barry Jenkins, left, and “La La Land” producer Jordan Horowitz embracing.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 6/60

Warren Beatty attempts to explain how “La La Land” was mistakenly announced as the best picture winner instead of “Moonlight.” (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

7/60

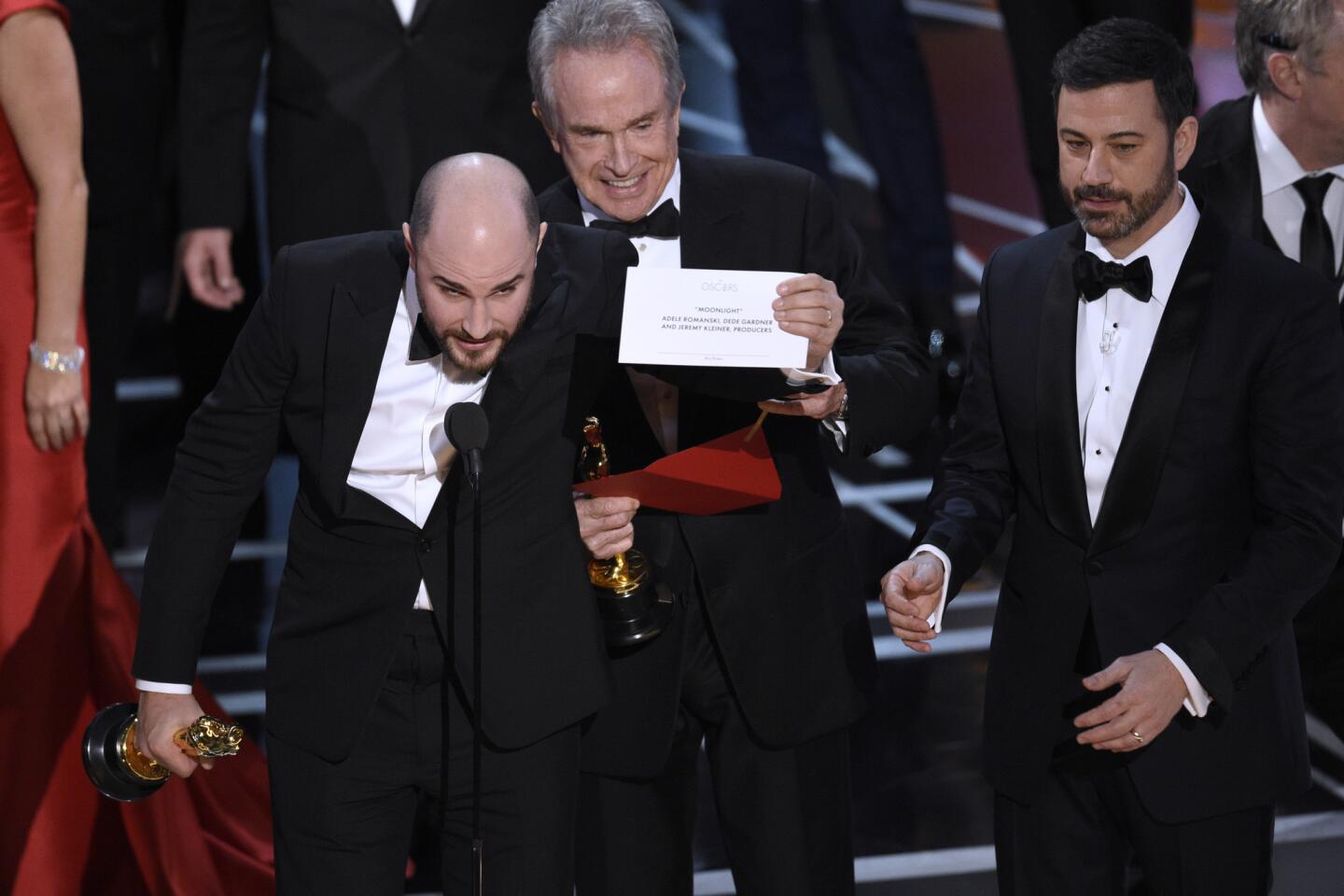

“La La Land” producer Jordan Horowitz, with Warren Beatty and host Jimmy Kimmel, after the mistaken annoucement that “La La Land” had won. “Moonlight” was the actual best picture winner.

(Kevin Winter / Getty Images) 8/60

Fred Berger, foreground center, and the cast of “La La Land” mistakenly accept the award for best picture at the Oscars.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 9/60

Accountants for Price Waterhouse Coopers take the correct envelope onto the stage after the best-picture mixup.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 10/60

Barry Jenkins holds up a best picture Oscar for “Moonlight.” (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

11/60

From left, “Moonlight” writer/director Barry Jenkins, and producers Adele Romanski and Jeremy Kleiner accept the Oscar for best picture during the Academy Awards telecast on Feb. 26.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 12/60

Janelle Monae reacts onstage after “Moonlight” won for best picture during the Academy Awards telecast on Feb. 26.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 13/60

“La La Land” producer Fred Berger, left, congratulates actor Mahershala Ali onstage after it was announced that “Moonlight” won for best picture.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 14/60

“Moonlight” actor Ashton Sanders is stunned after the movie won for best picture during the Academy Awards telecast on Feb. 26.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 15/60

“Moonlight” writer/director Barry Jenkins holds the Oscar for best picture during the Academy Awards telecast on Feb. 26.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 16/60

Mahershala Ali and Ryan Gosling backstage after it was announced that “Moonlight” won for best picture during the Academy Awards telecast on Feb. 26.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 17/60

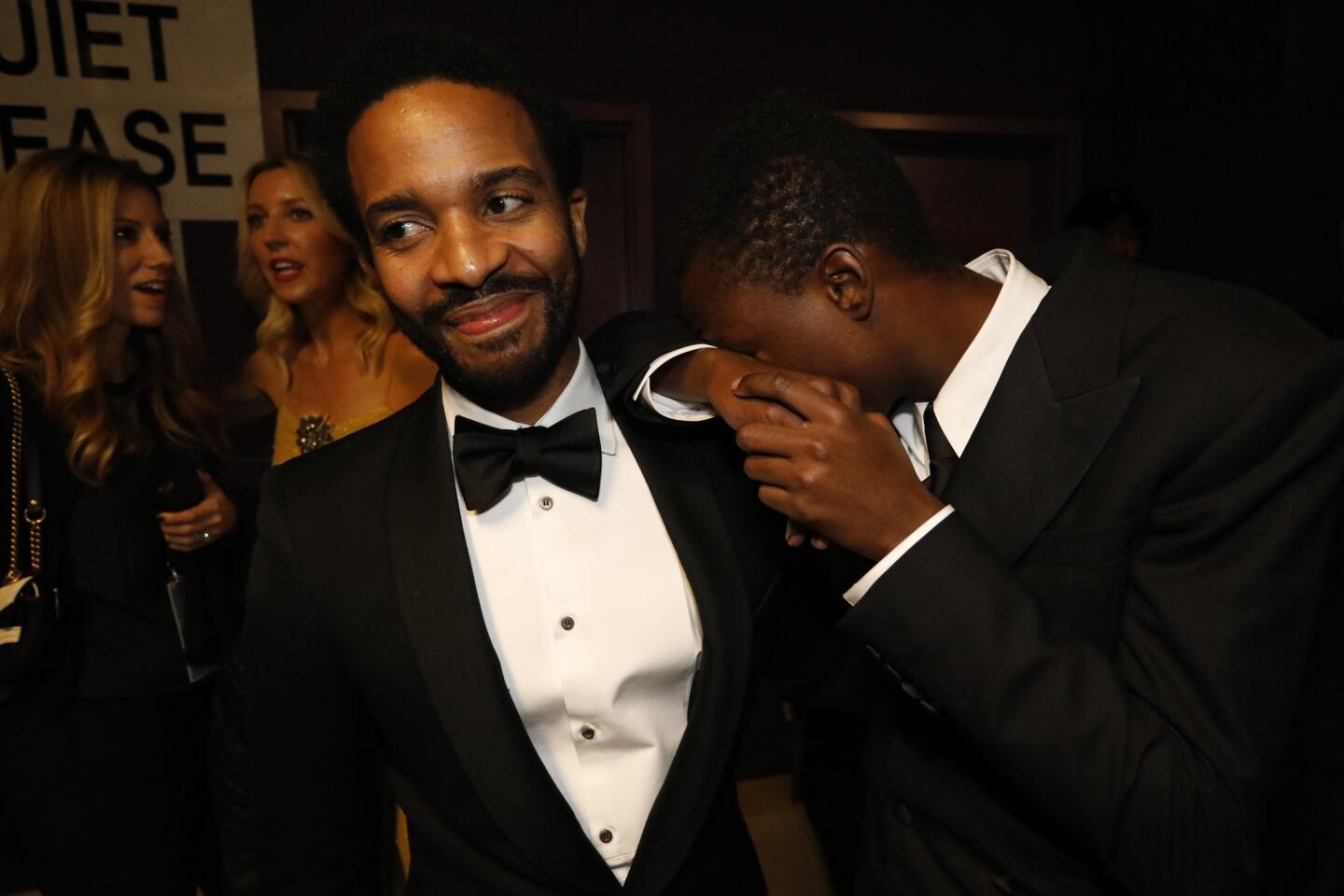

“Moonlight” actors Andre Holland, left, and Ashton Sanders backstage during the Academy Awards telecast on Feb. 26.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 18/60

“Moonlight” actors Andre Holland, left, and Ashton Sanders backstage during the Academy Awards telecast on Feb. 26.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 19/60

Barry Jenkins, center, and the cast and crew of “Moonlight,” which won the Oscar for best picture.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 20/60

Trevante Rhodes hugs Mahershala Ali after “Moonlight” was correctly identified as the winner of best picture.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 21/60

The cast and crew of “Moonlight” receives their best picture award after a chaotic mixup.

(Mark Ralston / AFP/Getty Images) 22/60

Presenter Faye Dunaway backstage at the Academy Awards.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 23/60

Ryan Gosling learns that his film, “La La Land,” did not win the best picture Oscar.

(Kevin Winter / Getty Images) 24/60

Producer Ezra Edelman takes a photo of his statue as it is being engraved after winning for his documentary, “OJ: Made in America.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 25/60

Presenters Michael J. Fox (left) and Seth Rogen (right) flank John Gilbert (center), who won a film editing Oscar for “Hacksaw Ridge.”

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 26/60

Adam Valdez, Andrew R. Jones, Dan Lemmon and Robert Legato pose with their visual effects Oscars for “The Jungle Book.”

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 27/60

Presenters Kate McKinnon (left) and Jason Bateman (right) flank Christopher Nelson, Giorgio Gregorian and Alessandro Bertolazzi, who won Oscars for makeup and hairstyling.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 28/60

“La La Land” star Emma Stone on stage with Leonardo DiCaprio after she won the Oscar for lead actress.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 29/60

Casey Affleck after he won lead actor for “Manchester by the Sea” during the telecast of the 89th Academy Awards.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 30/60

Damien Chazelle accepts the award for best director for “La La Land” from Halle Berry.

(Kevin Winter / Getty Images) 31/60

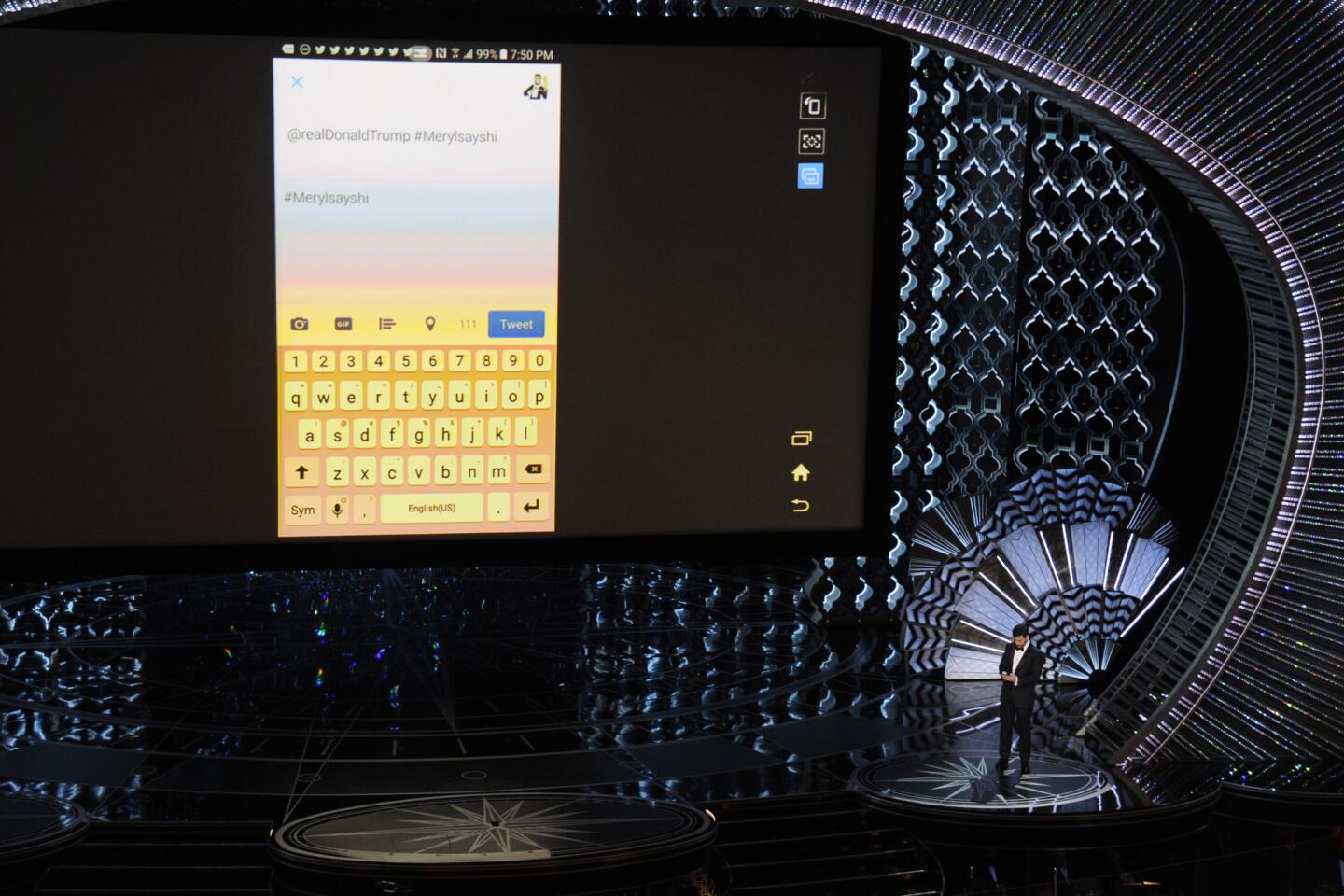

Host Jimmy Kimmel tweets that “#Merylsayshi” at President Trump.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 32/60

John Legend performs during the telecast of the 89th Academy Awards.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 33/60

Surprised tourists brought to the Oscars chat with celebrities in the front row.

(Mark Ralston / AFP/Getty Images) 34/60

Mahershala Ali, right, hands his Oscar to a tourist named Gary who was brought into the theater with others as a surprise.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 35/60

Denzel Washington, center right, “marries” an engaged couple during a surprise visit of a Hollywood tour bus group during the telecast of the 89th Academy Awards.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 36/60

Sting performs.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 37/60

Engineer and astronaut Anousheh Ansari, right, and former NASA scientist Firouz Naderi with the award for best foreign language film for “The Salesman.” They accepted on behalf of director Asghar Farhadi.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 38/60

Charlize Theron, left, and Shirley MacLaine.

(Kevin Winter / Getty Images) 39/60

Mahershala Ali, left, and Viola Davis, winners for best supporting actor and actress.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 40/60

Viola Davis accepts the Oscar for supporting actress during the telecast of the 89th Academy Awards.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 41/60

Viola Davis, winner of the award for best supporting actress, kisses Julius Tennon.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 42/60

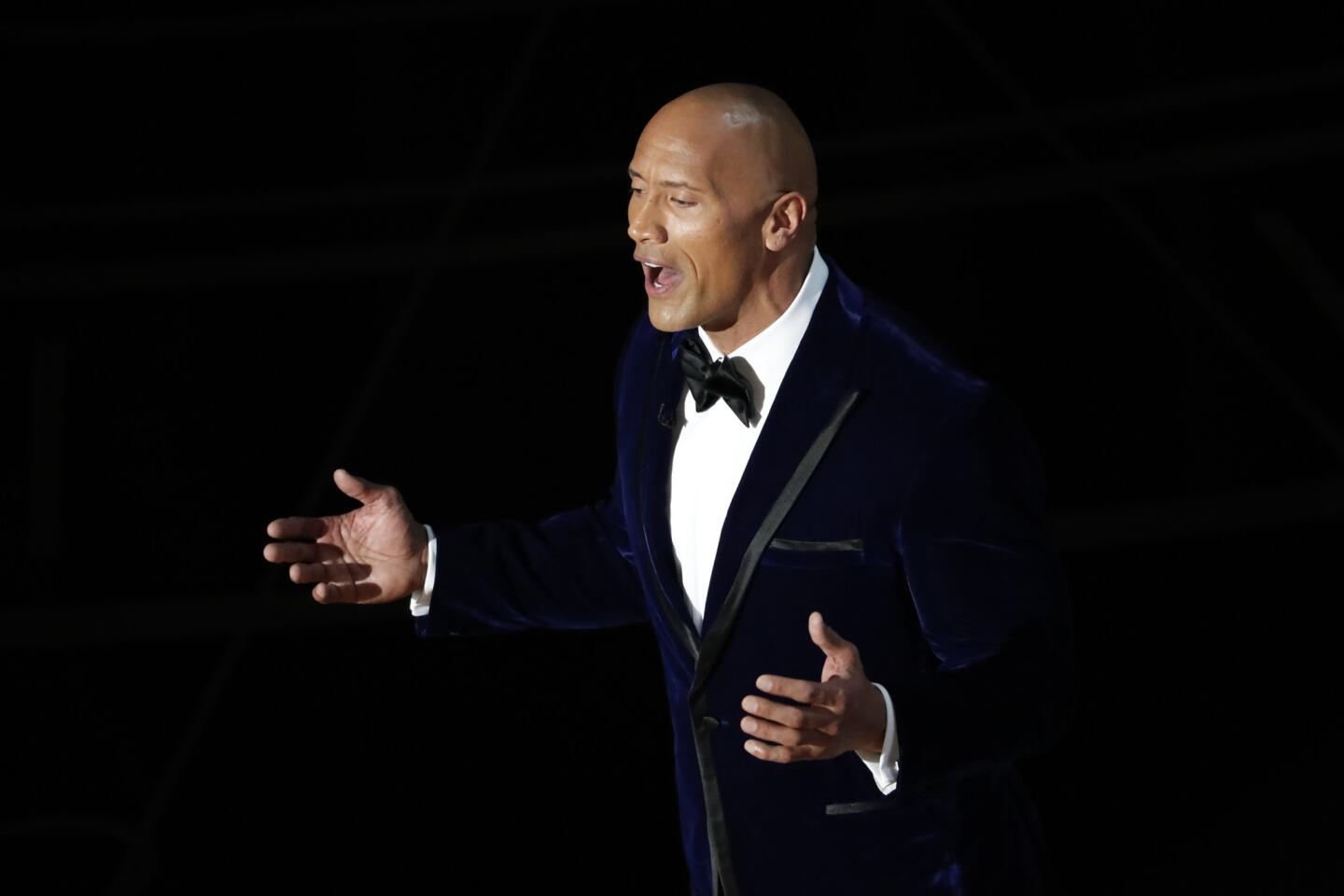

Dwayne Johnson sings a bit of “You’re Welcome” from “Moana” during the Oscars telecast.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 43/60

Kevin O’Connell, left, and Andy Wright accept the award for best sound mixing for “Hacksaw Ridge.”

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 44/60

Janelle Monae, Katherine Johnson, Taraji P. Henson and Octavia Spencer.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 45/60

Lin-Manuel Miranda raps during the telecast of the 89th Academy Awards.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 46/60

Auli’i Cravalho sings “How Far I’ll Go” from “Moana” during the telecast of the 89th Academy Awards.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 47/60

Producer Caroline Waterlow and director Ezra Edelman, winners for best documentary feature.

(Mark Ralston / AFP/Getty Images) 48/60

Mahershala Ali wins for best supporting actor.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 49/60

Alicia Vikander, left, presents Mahershala Ali with the award for best supporting actor.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 50/60

Host Jimmy Kimmel

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 51/60

Host Jimmy Kimmel

(Mark Ralston / AFP/Getty Images) 52/60

Justin Timberlake performs to open the show.

(Kevin Winter / Getty Images) 53/60

Justin Timberlake performs during the telecast of the 89th Academy Awards.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 54/60

Scarlett Johansson and date Joe Machota of CAA arrive at the 89th Academy Awards.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 55/60

Mayor Eric Garcetti makes an L.A. hand signal.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 56/60

Justin Timberalke and Jessica Biel arrive at the Oscars.

(Jordan Strauss / Associated Press) 57/60

Halle Berry on the red carpet.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 58/60

Sunny Pawar of “Lion” during the arrivals at the 89th Academy Awards.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 59/60

Chef Wolfgang Puck presents Oscars cuisine during the arrivals at the 89th Academy Awards.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 60/60

Chrissy Teigen and John Legend.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) Kimmel, whose demolition jobs are delivered with the smoothness of a barber giving an old-fashioned shave, had an irresistible target, and he certainly got in his share of presidential licks. But there was another famous figure in his crosshairs, Matt Damon, the good-sport target of a fake celebrity feud.

It wasn’t as if Kimmel lost sight of Trump during the ceremony. There was a hilarious bit late in which he tweeted the Tweeter-in-Chief to see if he might be secretly watching. (The absence of social media venom from the White House prompted the check-in.) But Damon served as a jocular safety valve, rescuing Kimmel from becoming too focused on the elephant not in the room.

The Oscars has many different audiences, not all of them natural couch-fellows. Experiencing the ceremony from inside the Dolby Theatre as a first-time attendee, I was fascinated by how the show managed the tightrope act of appealing to movie industry elites who dressed to the nines for the occasion and to the more casually attired viewers from all over the world who make up Hollywood’s maddeningly heterogeneous consumer base.

Producer Marc Platt, accepting the best picture award for “La La Land” (before it was discovered that, oops, the winner was really “Moonlight”), delivered an eloquent speech in which he made the distinction between “the Hollywood community” that he was so proud to be part of and “the Hollywood in the hearts and minds of people everywhere.” The show, acutely conscious of these two groups, found a way to speak simultaneously to them by appealing to what unites them — the basic human need to connect through storytelling.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

The word of the night was “empathy,” which liberals would be quick to read as an antonym of “Trump” and conservatives as code for Trump-bashing. But Viola Davis clarified the meaning in the context of the arts when she movingly accepted the supporting actress award for her performance in “Fences.”

Speaking with the intense emotional lucidity that is the hallmark of her acting, she immediately got down to brass tacks: “You know, there’s one place that all the people with the greatest potential are gathered. One place. And that’s the graveyard.”

Her mission as an actress, she said, is to exhume those bodies. Exhume those stories. The stories of the people who dreamed big, and never saw those dreams to fruition.” The kind of ordinary lives August Wilson, the author of “Fences,” devoted his exemplary career to resurrecting. “I became an artist and thank God I did because we are the only profession that celebrates what it means to live a life,” Davis said, transcending politics with the humanism of art.

There were speeches that editorialized more explicitly on Trump’s policies. Gael García Bernal took issue with the White House’s immigration plans, saying, “As a Mexican, as a Latin American, as a migrant worker, as a human being, I am against any form of wall that wants to separate us.” And a statement from Iranian director Asghar Farhadi, whose movie “The Salesman” received the foreign film award, explained that his absence was “out of respect for the people of my country and those of other six nations who have been disrespected by the inhumane law that bans entry of immigrants to the U.S.”

It was interesting to see up-close the mixed reaction to these political moments at the Dolby, where those not applauding were as conspicuous as those who were. Support for these positions clearly outweighed the silence, but “liberal Hollywood” isn’t the monolith imagined in conservative jeremiads. Some in the audience were simply not comfortable in expressing a political opinion, but a few others appeared to be wearing a look of weary forbearance.

No one, however, could argue with the basic thrust of the evening that dividing people into enemy camps isn’t the way to move forward or to stay sane. Opposition, as the brilliant Shakespearean actor Mark Rylance observed while presenting the supporting actress award, shouldn’t have to devolve into hatred. Even a liberal stalwart like Warren Beatty hewed to this message, prefacing his presentation of the night’s final award with the idea that “our goal in politics is the same as our goal in art. And that is to get to the truth.”

The truth that collected trophies on Sunday was more diverse than the previous year that gave us the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite. This was a cause of celebration. The academy had taken steps to respond to the outcry that it wasn’t doing enough to expand its tent. Hollywood still has entrenched structural problems, but the Oscars had reason to pat itself on the back, even if the bungling of the evening’s top prize cheated “Moonlight,” the first LGBT film to win for best picture, of its turn in the sun.

1/15

Presenters Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty are onstage and about to read the Oscar winner for best picture.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 2/15

“La La Land” producer Jordan Horowitz points to “Moonlight” as being the winner of the best picture Oscar.

(Kevin Winter / Getty Images) 3/15

Jordan Horowitz, producer of “La La Land,” shows the envelope revealing “Moonlight” as the true winner for best picture.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 4/15

“La La Land” producer Jordan Horowitz hands over the best picture award to “Moonlight” writer-director Barry Jenkins after a presentation error onstage.

(Kevin Winter / Getty Images) 5/15

“Moonlight” cast members Mahershala Ali and Trevante Rhodes hug after winning Best Picture for “Moonlight.”

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 6/15

Oscars telecast host Jimmy Kimmel, left, with Warren Beatty, who explains how “La La Land” was mistakenly announced as best picture winner instead of “Moonlight” at the 89th Academy Awards.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 7/15

Presenter Warren Beatty shows the envelope with the name of the actual winner for best picture as host Jimmy Kimmel, left, looks on.

(Chris Pizzello/Invision / Associated Press) 8/15

“Moonlight” actor Mahershala Ali, left, with Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone after it was discovered that “La La Land” was mistakenly announced as best picture onstage.

(Kevin Winter / Getty Images) 9/15

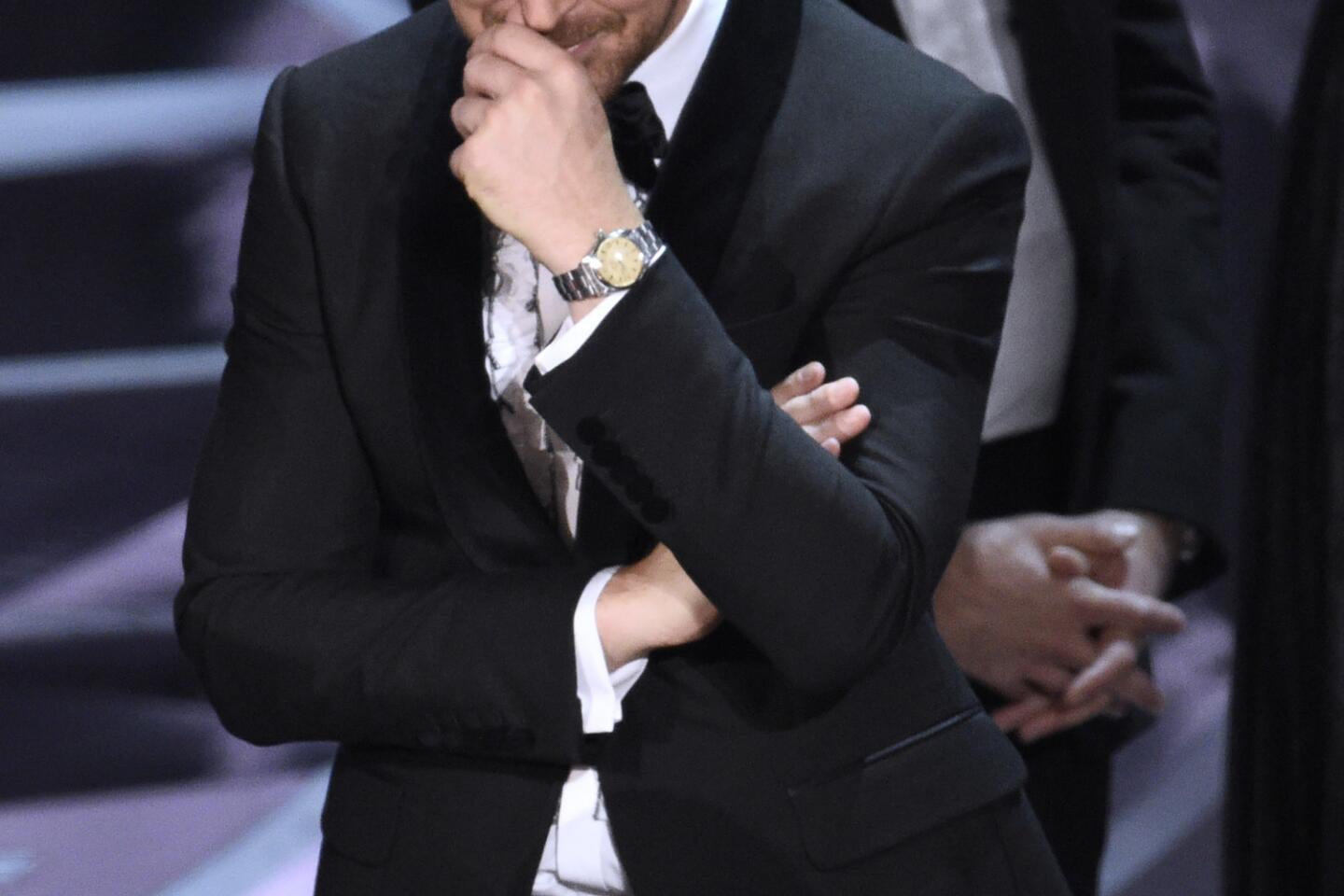

Ryan Gosling, right, stands with arms folded as Emma Stone congratulates Mahershala Ali of “Moonlight.”

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 10/15

Ryan Gosling of “La La Land” reacts as the true winner for best picture is announced.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 11/15

Janelle Monae, center, celebrates after coming onstage once the best picture mix-up was announced.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 12/15

Barry Jenkins, left, and producer Adele Romanski appear both stunned and celebratory after “Moonlight” won the Oscar for best picture.

(Mark Ralston / AFP / Getty Images) 13/15

Barry Jenkins, front left, and the cast accept the award for best picture for “Moonlight.”

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 14/15

Cast and crew of both “Moonlight” and “La La Land” are onstage.

(Mark Ralston / AFP/Getty Images) 15/15

“La La Land” producer Jordan Horowitz, left, speaks to a Oscars show producer, who is reading the winners card after “La La Land” mistakenly was announced as best picture winner instead of “Moonlight.”

(Mark Ralston / AFP / Getty Images) Audience members at the Dolby, many of whom were connected to particular films, didn’t know how to react when it was announced that “La La Land” had been mistakenly given the award. Some supporters of the film shook their heads in dismay while “Moonlight” champions, given an unexpected reprieve, seemed to distrust their joyous windfall. It was a surreal ending, but progress can be a slippery ride and there was happy amazement that a small-budget film about a young gay protagonist of color managed to pull off such a feat.

As a theater critic, I was heartened to see the way theater and film have become so entwined (an especially fetching sight on Tony-winning scenic designer Derek McLane’s gorgeous Hollywood Golden Age set). Picking up awards were playwrights (Kenneth Lonergan, the writer and director of “Manchester by the Sea,” and Tarell Alvin McCraney, whose play gave rise to “Moonlight”), Broadway songwriters (Benj Pasek and Justin Paul of the Broadway hit “Dear Evan Hansen,” who contributed to the songs of “La La Land”) and actors with deep theatrical roots (such as the Juilliard-trained Davis, a Tony and Obie winner, and NYU-trained Mahershala Ali, who thanked his illustrious acting teachers).

Lin-Manuel Miranda (the suddenly ubiquitous genius behind “Hamilton”) and Sara Bareilles (the stunningly talented singer-songwriter who wrote the score for the Broadway musical “Waitress”) added to the polished verve of the show through their musical performances. All of the numbers were executed with such Broadway precision that I kept forgetting that they were being televised worldwide.

As Hollywood seeks to widen its range of stories, it only makes sense that it would turn to the theater, which has traditionally been more welcoming of marginalized voices. Embracing diversity not as a political platform but as a human imperative is an effective way of rebutting the charge of elitism that has been leveled at the arts by conservative ideologues.

The one discordant note of the evening was the overextended segment in which Kimmel had tourists troop through the glamorous audience and intermingle with their favorite stars. In a show that was all about dissolving the line between us and them, this comedy routine inadvertently reinforced the old divisions while chasing after cheap laughs.

But this was the exception in a highly theatrical night that was brilliantly calibrated to remind us of the power artists have to unite us through cinematic storytelling. It is through this magical lens that the most distant and disparate lives are brought into close proximity and the strange suddenly become uncannily familiar.

charles.mcnulty@latimes.com

Follow me @charlesmcnulty