Review: Getty exhibition makes a case for the enduring power of Theodore Rousseau

Is there a fate worse for a painter than being remembered primarily as a “precursor” to a later, very major development in the history of Western art?

Take Theodore Rousseau (1812-1867), the subject of a fine, newly opened survey exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Once he had been celebrated for textured landscape paintings of the French countryside, especially the fabled forest of Fontainebleau 40 miles southeast of Paris. Now he is mostly extolled for a leading role in opening the door on Impressionism, which blossomed after his death.

Precursor to Monet! And Cezanne!

More than Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, more than Charles-Francois Daubigny, both of whom also worked in Fontainebleau, Rousseau ranks as perhaps Western art history’s Precursor in Chief. The title doesn’t merely damn with faint praise, it misrepresents his achievement.

Yes, the implication is that the extravagantly talented painter was forward-looking — on to something fresh that escaped most of his colleagues. Better than being retrograde.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

But it also says that, in Rousseau’s own work, he (and the precursor business is always a he) didn’t quite make it to deep significance. Rather than bother looking hard at the paintings on which he labored, best to give them a once-over and move on to the watershed that he heralded.

Being a precursor might be better than not being remembered at all, but it’s also vexed. “Unruly Nature: The Landscapes of Theodore Rousseau,” co-organized by Getty curator Scott Allan and Edouard Kopp, drawings curator at Harvard Art Museums, does a good job of un-vexing it. The show refocuses on the artist’s own work.

There hasn’t been a Rousseau survey since the Louvre Museum marked the centennial of his death in 1967. These 71 paintings and works on paper constitute the first retrospective ever in North America. (The show’s only other stop will be in October at its co-sponsor, Copenhagen’s Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.) It’s engrossing, even if Rousseau doesn’t emerge as a painter of the first rank.

Rousseau was just 55 when he died, weakened by lung disease. Three tight galleries follow a loose chronology, while an anteroom assembles 13 small works on paper and canvas for a thumbnail overview of his career.

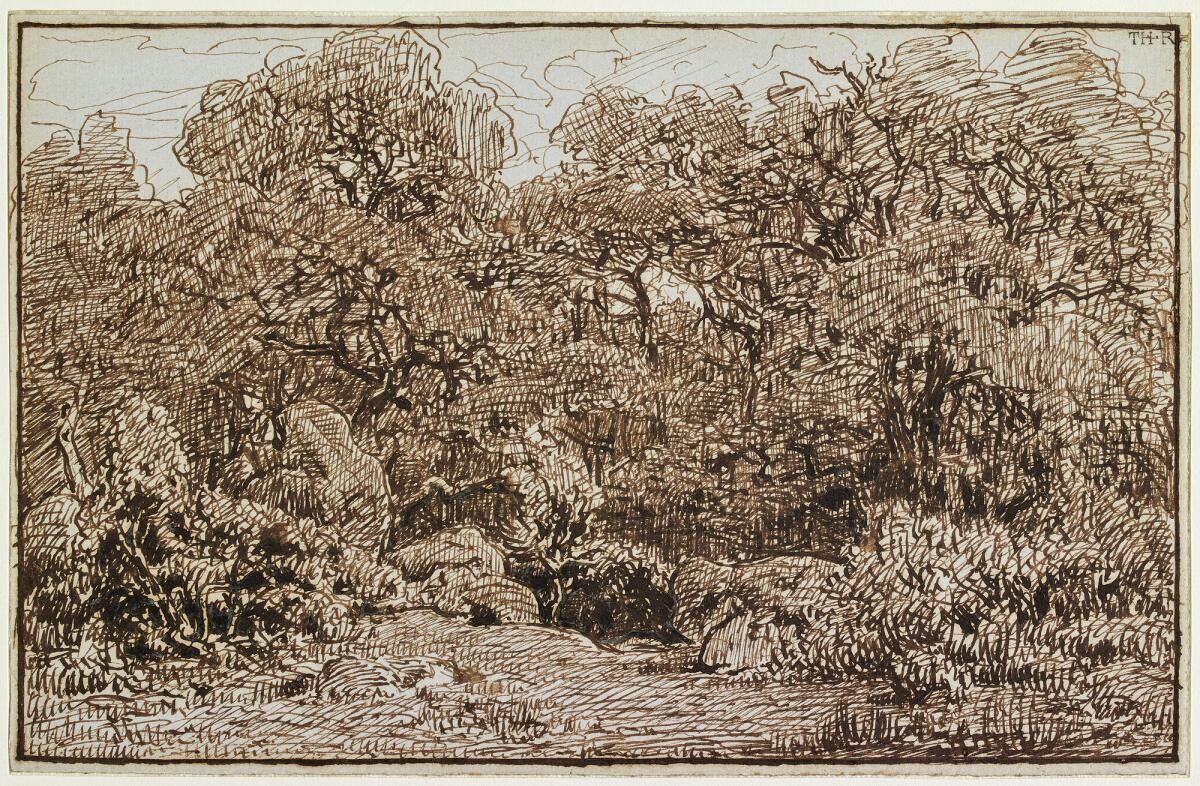

An agitated drawing in pen and ink of a rocky woodland, executed as a teenager, represents landscape as sense impression, a torrent of quick marks. Five or so short years later, “Alley of Chestnut Trees” shows an orderly, organized march through a deep, lush sequence of arching limbs.

His effortless skill as a draftsman is impressive. What he would do with that talent is revealing. From the first drawing to the second, Rousseau transformed the landscape of France from rowdy natural tumult to luminous, measured cathedral.

France was something of a mess in the decades after the revolution. The country ricocheted from monarchy to republic to empire. Europe (like North America) was busily birthing nation-states. For painters, the subject of the landscape, once minor, began to gain major traction.

John Constable in Britain, Jose Maria Velasco in Mexico, Albert Bierstadt in the United States, Caspar David Friedrich in Germany and many, many more — including Rousseau — invented a problematical vision of “the homeland.” The naturalism and specificity of the local landscape, whether monumental volcanoes in Mesoamerica or misty mountain tops in Central Europe, were infused with portentous meaning.

The old idea of the landscape as a historic place of grand events and literary myths gave way to a more objective chronicle of rocks, trees and light. Naturalism met nationalism, and identity fused with the land.

Rousseau did it in two principal ways, each implied in those two early drawings of a rocky woodland and a chestnut alley.

First, the forest primeval was his great subject. The chestnuts and ancient oaks of Fontainebleau replaced the elders of church and state as cultural symbols of enduring power, mystery and beauty.

And second, the showy, painterly mark of the artist’s vigorous brush identified Rousseau’s presence in the particular time and place recorded in the chosen landscape. Paint carried his distinctive, recognizable artistic fingerprint.

Luxurious painterly qualities always favor the surface of a canvas. Space flattens out. Depth is physically shallow. Looking out over distant fields or into dense forests punctured by clearings is suggested through a marvelous layering of light.

“A Swamp in Les Landes” is a cloud-covered, atmospheric view of marshland in the heaths of southwestern France. It is stabbed with bright white pigment at the bottom foreground, as well as in what appears to be a middle-ground coastal edge and, through backlighted clouds at the top, in the far distance. Darker sky and earth recede as Rousseau’s daubed light breathes air into the clotted, gloomy swampland.

It’s a landscape of hope and possibility.

These paintings are of course fabrications. After sketching trips into the Fontainebleau forest and elsewhere, most were painted in the artist’s studio in Paris or the rustic little town of Barbizon. None is more exemplary than the histrionic thunderstorm that roils “Mont Blanc Seen From La Faucille, Storm Effect,” his largest canvas and one of his most famous.

The vista was inspired by a youthful visit to the Jura Mountains in a high alpine pass near the Swiss border, but it unfurled in Rousseau’s studio. Landscape becomes spectacle, a painted drama of snowy peaks beneath flashing white lights and angry black clouds, the fields below interrupted by rocky outcroppings and dense brambles of vegetation.

The artist kept the big painting in his studio for three decades, presumably adjusting its effects over time. This masterpiece of Romantic bravura pointedly tangles up artistic conception with natural creation.

“Mont Blanc” embodies Rousseau’s powers of invention, even though it is finally unlike anything else he ever did. He returned to the subject at the end of his life, producing a painfully awful picture — an acutely detailed, this time sunny panorama of inert, airless little color patches. (Think mosaic tabletop from a tourist gift shop.) It’s in the show’s last room, a gallery that ends his relatively short career with more of a whimper than a bang.

The chief exception is the magnificent “The Rock Oak” (circa 1860-67), painted with a thick, dark impasto that infuses its benign forest-subject with a fearsome quality. The canvas shows a gnarled oak rising up from a craggy terrain. (Fontainebleau is noted for its rock formations.) A taut pinwheel arrangement of branches crowns the tree.

The closer one gets to the opaque, densely painted picture, the more abstract and illegible it becomes. The concentrated greens and burnt umber of its edge-to-edge woods approach a fossilized carbon-black, peppered here and there with flecks of light. The deep forest is a wondrous place, vaguely threatening yet capable of igniting astonishment.

It’s worth remembering that city folks were the chief audience for Rousseau’s rural landscape musings. The narrow, medieval streets of Paris were teeming with people, the city’s population having doubled between 1815 and 1850. Rousseau was showing France whence it had come.

Soon, grand boulevards would cut a swath through the civic fabric, as the Paris we know today was built. Impressionism was handmaiden to this vibrant new city. Rather than a precursor, Rousseau’s landscapes, often melancholic, represent something marvelous, remote and slowly disappearing from consciousness.

------------

“Unruly Nature: The Landscapes of Theodore Rousseau,” J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood, through Sept. 11. Closed Monday. www.getty.edu

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.