Q&A: Artist Jaime Hernandez reunites his ‘Love and Rockets’ women, but loves only one now

It is by now a piece of comic book lore: In 1981, a trio of brothers from Oxnard — Jaime, Gilbert and Mario Hernandez — self-published a slim black-and-white comic book they titled “Love and Rockets.” The volume, reprinted the following year by Fantagraphics, contained a riff on old monster flicks by Gilbert and a wild tale about a rocket mechanic named Maggie and her punk rock friend and sometime lover, Hopey, by his younger brother, Jaime.

Thirty-eight years have gone by, and Los Bros Hernandez, as they are known (principally Gilbert and Jaime), are now regarded as maestros of the comic book form. Some of the narratives they established in that first unlikely booklet are still going strong.

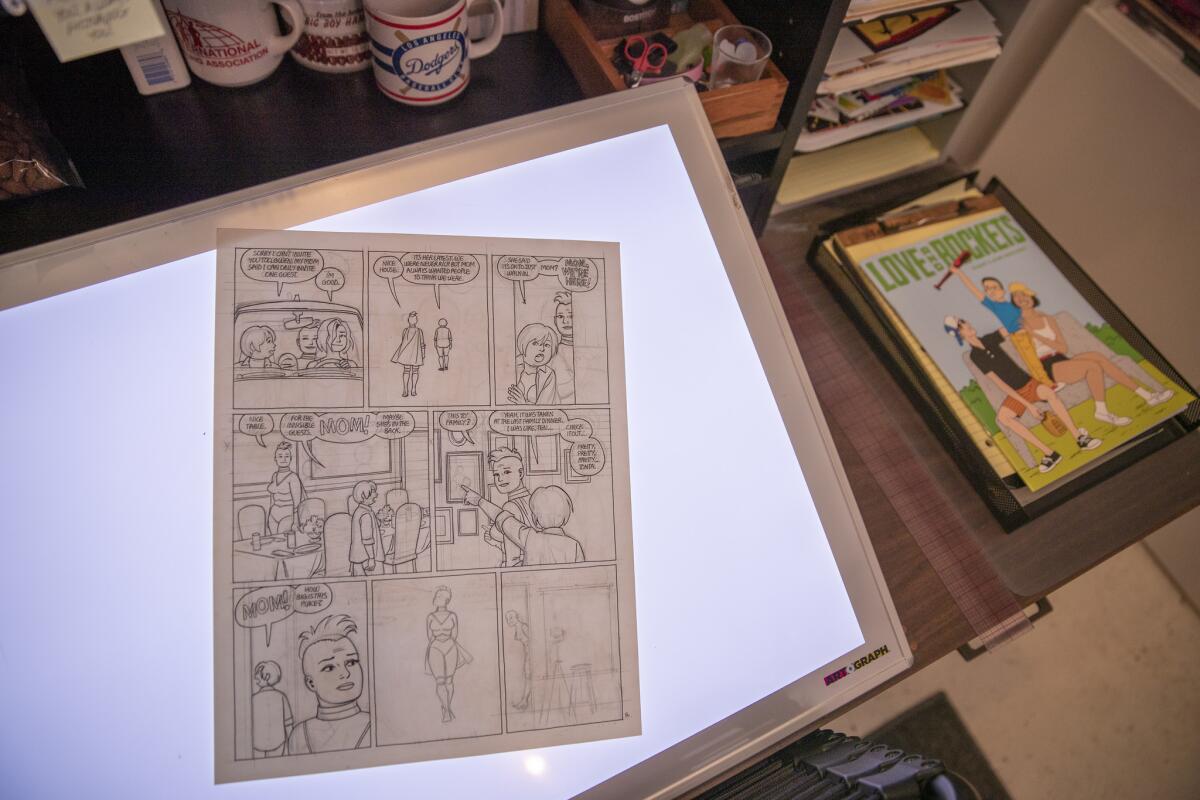

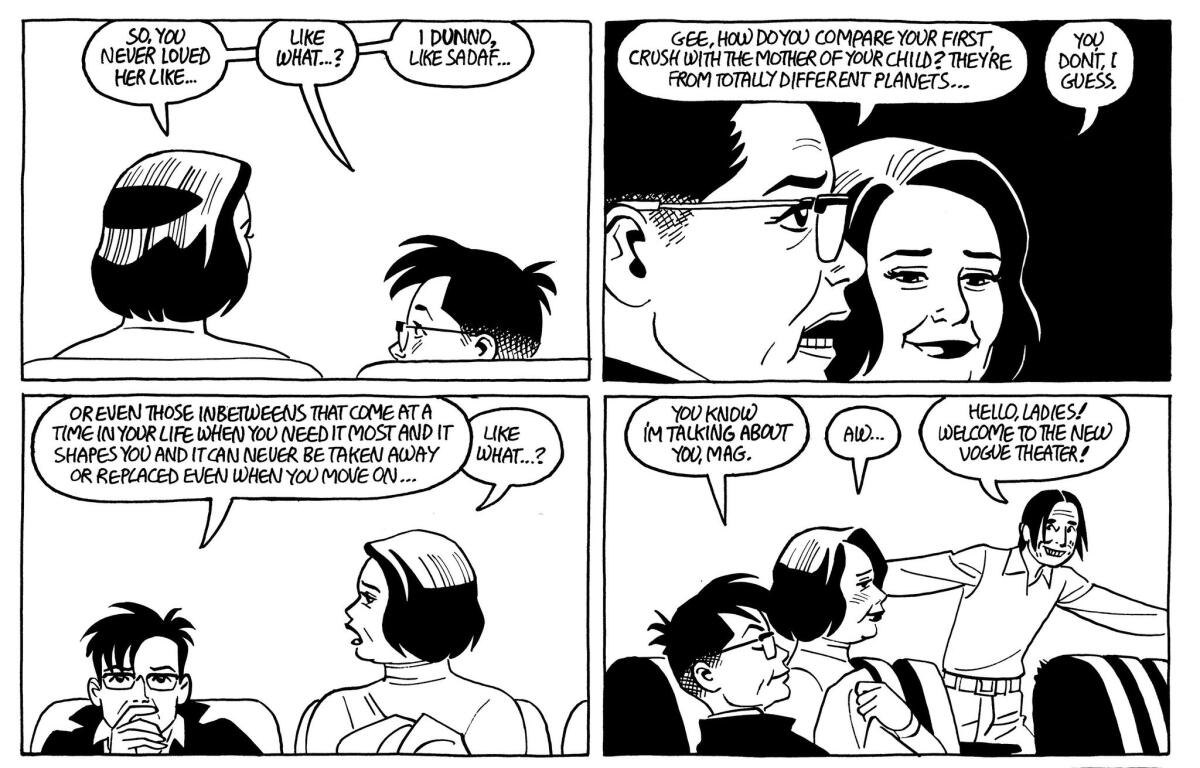

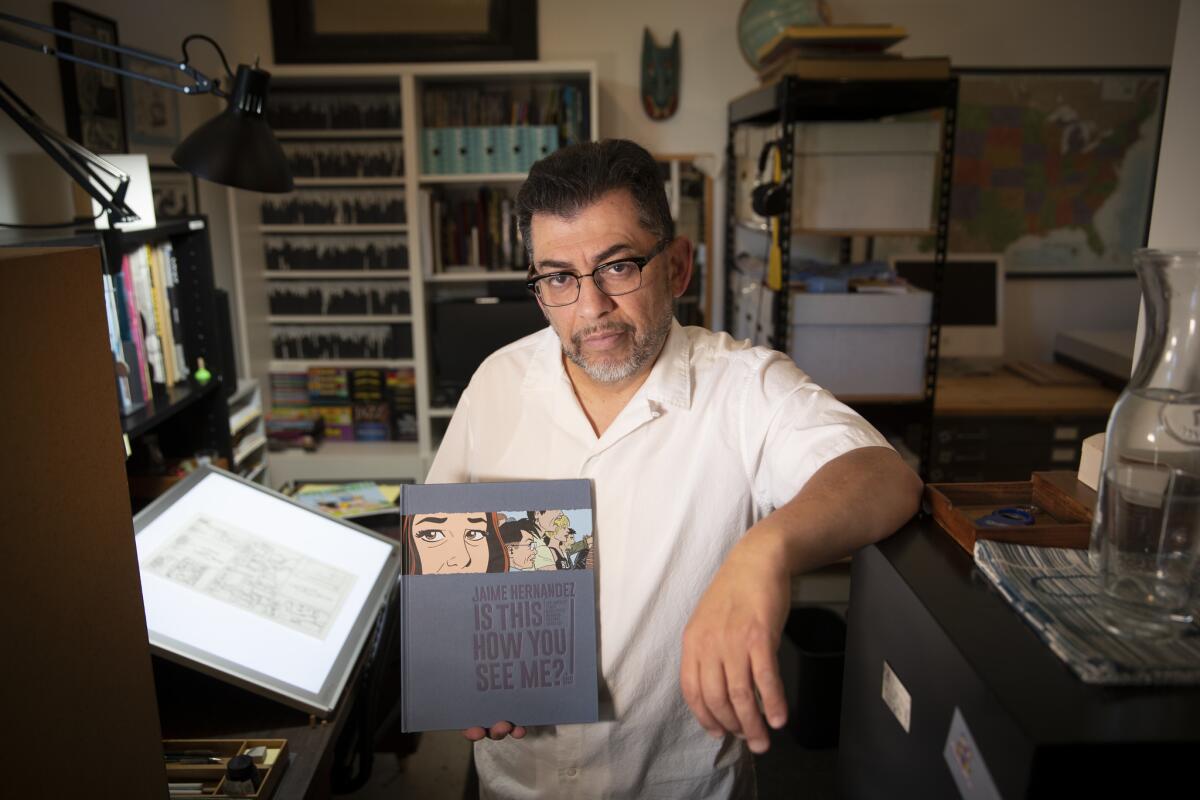

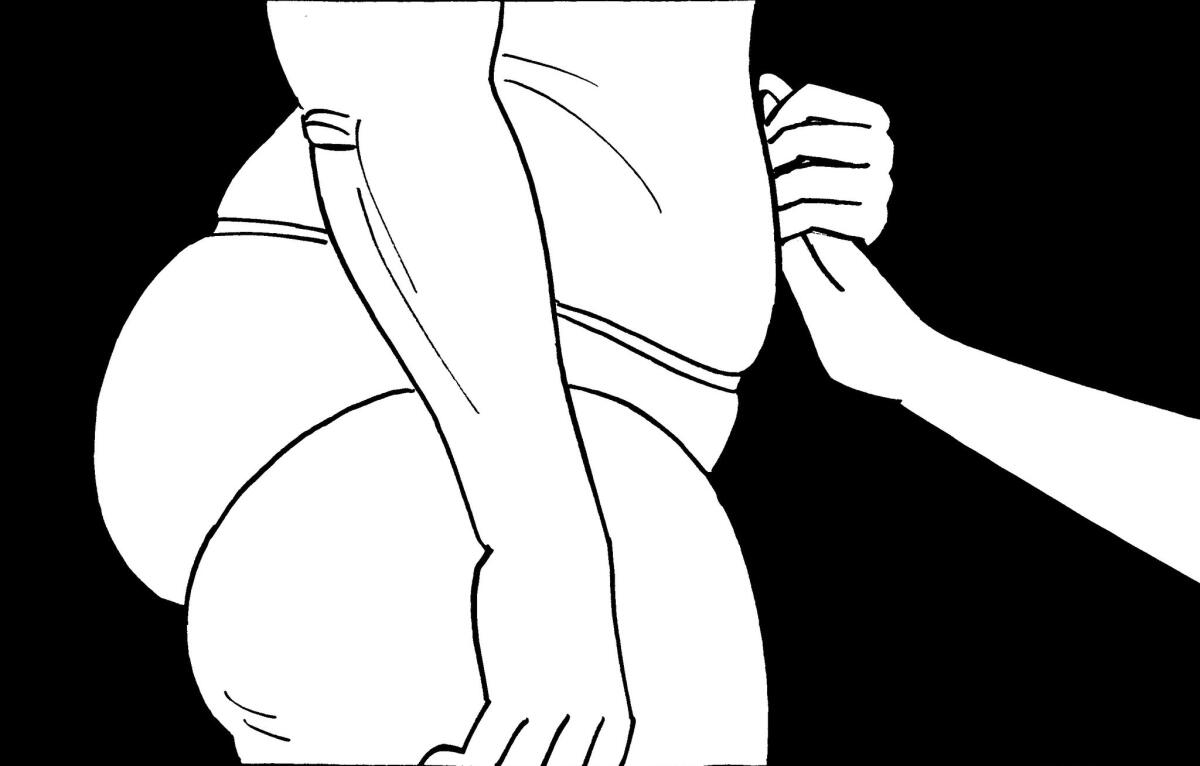

This month, Jaime is releasing “Is This How You See Me?” in hardback. It reunites Maggie and Hopey — now solidly in middle age — at a punk concert in fictional Hoppers (a stand-in for Oxnard). Almost four decades on, Maggie remains an impetuous romantic with a penchant for infatuation. Hopey, the take-no-prisoners punk, has sacrificed adventure for predictability. All these years later, the tangled relationship between these women still crackles.

“It’s been a while with them together,” Jaime Hernandez says. (Maggie and Hopey haven’t appeared in a comic together since 2014.) “I was happily surprised the way some of the characters were going in the story. I was happily surprised that some of them surprised me.”

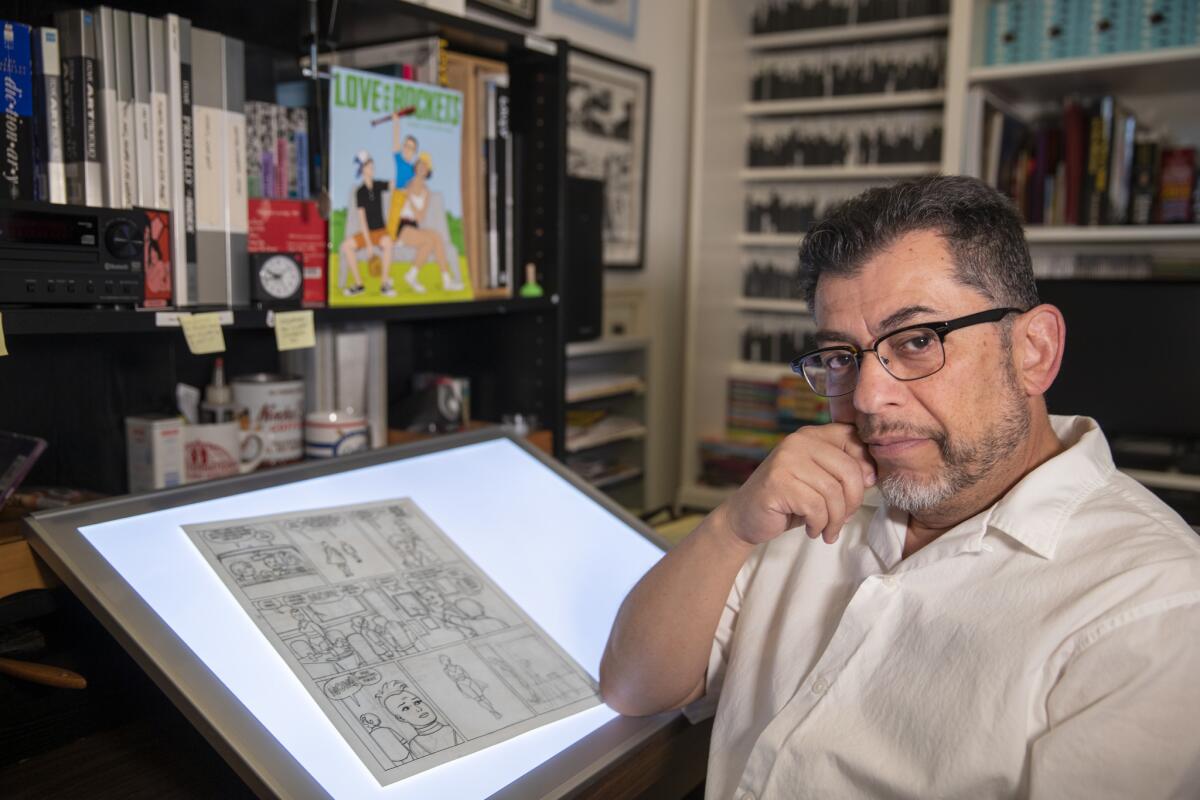

It’s not likely to surprise readers of “Love and Rockets,” however, who have grown accustomed to Hernandez’s elegant ink drawings (he still does everything by hand) and incisive psychological deconstructions of human emotion, be it love or enmity, ecstasy or pain.

This accomplishment is more remarkable given the fact that Hernandez’s characters are principally women. They are also principally Latina — making “Love and Rockets” the rare pop cultural artifact that renders Latinas not as archetypes, but as rich and profound human beings full of messy contradiction and ambivalence.

Over the years, Hernandez’s characters have aged and their hairstyles have become more sedate. Some of their faces have grown angular; their bodies, more doughy. In the new comic, in which a group of former punks attempt to relive their youth for a weekend, a group of women joke about menopause in refreshingly real ways.

Recently, Hernandez took time to chat in his tidy — to the point of monastic — studio space in Pasadena. In this interview, condensed and edited for clarity, he discusses how he assembles his characters, why punk music is so vital to his narratives and what the movies get wrong about Latinos. (Hint: It involves a tortilla metaphor.)

What’s it like to check in with these characters every so often?

I have to admit that with Hopey changing so much, it was hard writing her into this new story. I didn’t really like her. I thought, I don’t like her as a person. I don’t like what she’s doing. I don’t like how her life turned out. She is one of those friends you’re disappointed in.

But I really like where Maggie goes. I like her because she screws up all the time. She wears her heart on her sleeve and I want you to know everything that she’s thinking. With Hopey, I don’t want you to know everything. There are certain characters, you don’t want to know what they’re thinking.

ALSO: Crafting ‘Love and Rockets’ with a punk attitude »

You’ve said that your characters are often based on people you know or stories you hear.

I base it on stories of people I know. Or their haircuts. Their personalities. I take different parts.

Like Frankenstein?

Yes. And Maggie is the most Frankenstein of all. I created a monster. [Laughs.] She swallows up a story.

I also really like the character of Daffy. She’s the one trying to keep the peace. She’s appeared a lot in the past. But here, I’m really happy she played a big role. I always liked the character, but she couldn’t compete with the other two — the big personalities.

What of yourself do you see in your characters?

I guess I see me more in Maggie. Just her decisions, the heartbreak, falling in love, yearning for someone, wanting to get along when the world doesn’t want you to. Though she’s gone and left me, in a way. I’m doing her from afar now.

What led you to create Maggie in the first place?

We had been drawing comics for ourselves since we were little kids. By the time I was in high school, I’d created Maggie, but she was a woman in outer space. I wanted a story about a woman I could put in any situation possible. As I grew up and evolved, she grew up and evolved. I got into punk. She got into punk. She came from the barrio. I came from the barrio. By the time “Love and Rockets” came around, she was who she was. And by that time we were in our early 20s, we didn’t want to do “The X-Men.” We were done with superheroes. I was like, I want to do my stories.

This was 1981 and there wasn’t an alternative market — not a big one. So, in a way, we were up against the two big superhero companies. But we didn’t care about that because we were two cocky punk rockers who were like, “Let’s do it.”

Punk music is really formative to the Maggie and Hopey story line. Why was it so significant to you?

I grew up with a cultural revolution. I was 4 years old when the Beatles invaded America. Pop music, soul — all of that was going on when I was growing up. In the early ’70s, my brothers got into glam. We were the only rock ’n’ rollers on the block. Everyone else was into Top 40 or soul or funk. It was the mid ’70s that I got into KISS. Then we discovered punk and never looked back. “You mean you can go see a band that’s right in front of you and you don’t have to be in a big stadium sitting a mile away?” I was like, “I’m here, man.”

Did you come to L.A. regularly to see concerts?

We tried to come once a week, but it was whoever had a car and who could afford gas. It was really fun. It was really diverse, all colors and genders — X, Black Flag, the Go-Go’s, the Bags, the Weirdos. There was the original base of the Hollywood punk scene, but I also grew up on New York and London punk. Then Oxnard got its scene and it’s like, oh, you don’t have to leave town anymore.

That’s how Maggie and Hopey came about. I’d go to these punk shows and I’d see women running the place and I loved their big mouths. They were doing something and they didn’t care. I wanted my Betty and Veronica, but with that mentality, with this real life kind of of thing going on. Gilbert and I were like, nobody’s doing this — let’s show the world that the world we come from is waaaay more interesting than a Marvel comic.

Why do women appeal to you so much as characters?

That’s always the hardest thing to answer. They just are. I like hanging out with women more than men most of the time. I remember early on in the mid-’70s, Gilbert was very feminist. I remember Gilbert being like, “Don’t call ’em broads,” and me being, “Oh, gee, I’m sorry.” I remember I hooked on to that — there’s gotta be this respect going on. I became very sensitive to it.

In many cases, women will talk about a farther range of emotions in a story. You’ll get five emotions from a woman and you’ll be lucky to get two from a guy because we’re so guarded. I’m a dude, but I listen very closely to the way my wife speaks about things, the way she talks about herself and her friends, what they go through. I just try to listen and put it in there.

Review: An engaging biography records the polemical life of architect Philip Johnson »

Your stories often include touches of the surreal. Where is that drawn from?

Mostly from stories about the old country. From my mom and my grandma and my tías — like ghost stories and odd stories about the neighbor and this and that. Down the street there was a house with a huge palm tree and there was a white owl that lived in the fronds and my mom — I think it was my mom — she said, “You see that white owl? That white owl lives there because the old lady there is crippled because some witch has put a curse on her.” So if a white owl lives in the neighborhood it’s because someone has a curse.

I always liked that quirkiness — that there were weird things going on next door and you just go about your life.

In a 2004 interview, you said there were parts of your work you weren’t sure would ever be accepted because “I don’t know if my culture will ever be accepted.” That was 15 years ago and ...

We’re still not accepted. There have been breakthroughs. They give us a movie, but at the same time, they want to put our children in cages.

Artist Harry Gamboa Jr. has said that there is a vacuum of representation when it comes to Mexican Americans — and that this vacuum is easily filled with misperception.

They’re still making movies wrong. You go to a movie about Latinos and the guy comes into the kitchen and his mom is cooking and she’s like, “Ay, m’hijo.” [Hernandez pretends to stir a pot beatifically.] Well, what about the guy like me who gets a tortilla and puts it on the burner and it chars and your mom yells at you? Or she’s like, “You’re eating now?” My brother and I for years have called [that phenomenon in the movies], “The tortillas are warm.”

Maggie and Hopey are getting older. Is there a future in which one of them might die?

Yeah, but I’m not sure when. I’m going to be 60 in October. I can see an end to this. My brain will go or my hand will go. My ideas will go. But so far it’s still working. I still got stories to tell.

“Is This How You See Me?”

Jaime Hernandez

Fantagraphics, 92 pp., $19.99

carolina.miranda@latimes.com | Twitter: @cmonstah

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.