How artist Sandy Rodriguez tells today’s fraught immigration story with pre-Columbian painting tools

- Share via

Riffle through Sandy Rodriguez’s dense rack of painting supplies and you’ll turn up feathers, withered plants and a container of cochineal powder, the fiery red tint produced by the insect that feeds on the leaves of the prickly pear cactus. You might also find a jar of bulbs from the orchid Laelia autumnalis, known as flor de los muertos (flower of the dead) in Mexico, where it primarily grows.

“I found these at a nursery in Santa Barbara,” says Rodriguez, holding up a tiny bulb. “You take the bulb, remove the exterior layer with a potato peeler, then you boil it, slice it, dry it, then you grind it. It becomes a gum and it stabilizes color. A berry color mixed with this will last 500 years.”

Rodriguez’s Mar Vista studio is part painting studio, part scientific lab. Here, the artist crafts the natural tints and other materials used in the works now on display in “Codex Rodriguez-Mondragón,” her solo exhibition at the Riverside Art Museum, and in the group show “Here,” currently on view at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery.

For two years, Rodriguez has been studying natural sources of color — plants, flowers, insects and oxides — and has researched historical methods of preparing them, including indigenous techniques that predate European colonization. (Those orchid bulbs? She located them via a friend who studies medieval history and supplied her with a recipe for how to prepare them.) But it’s not just her materials that nod to the past. She has used these pigments in a series of paintings inspired by the elaborate codices of the Mexican colonial era.

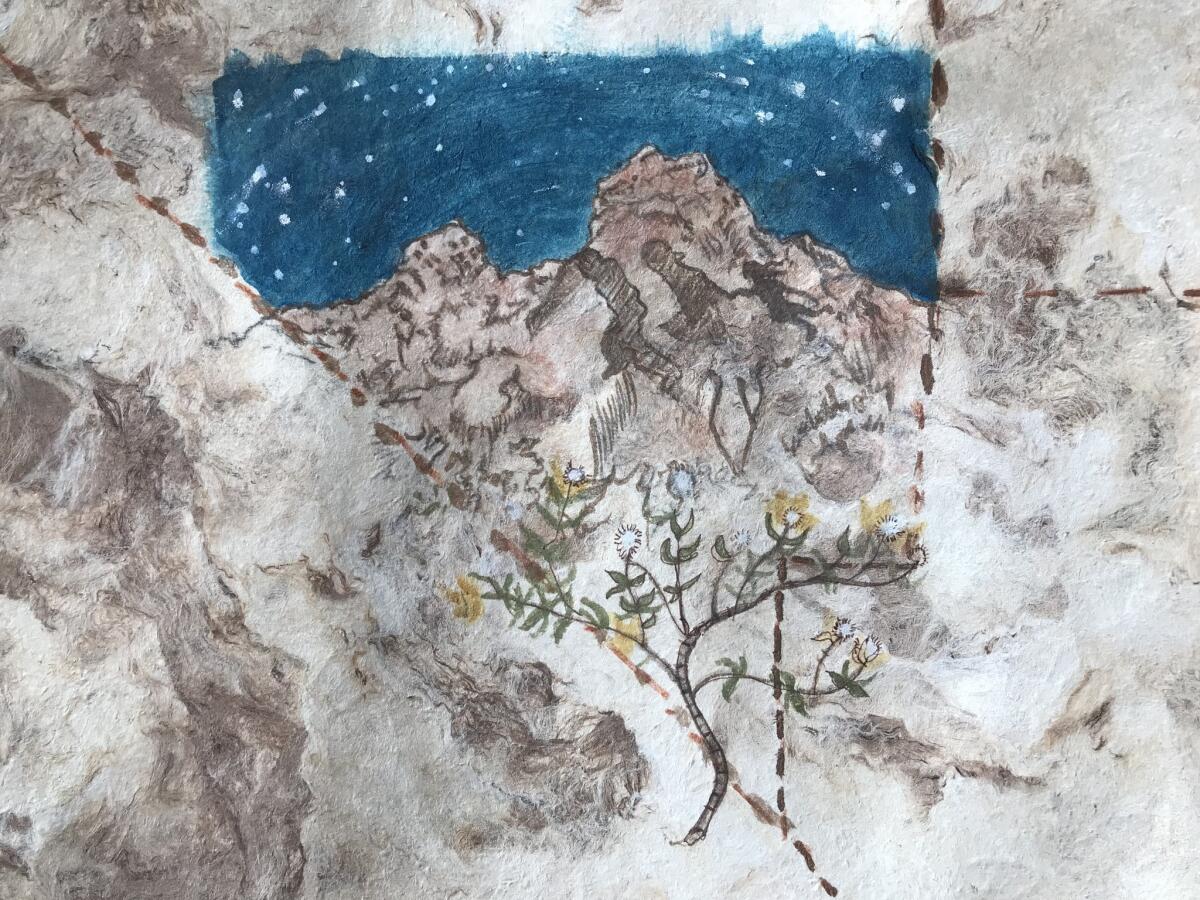

The series, titled “Codex Rodriguez-Mondragón,” after her father’s and mother’s surnames, serves as a curious record of our time. Like colonial codices, her paintings function as literal and cultural maps, delineating borders and capturing aspects of the landscape, including flora and fauna. But they also record the current political moment — in particular, issues of immigration. Look closely at one of Rodriguez’s large-scale map paintings and you will find images of protests, deportations and the tent city where migrant children, separated from their parents, are warehoused in Texas.

“At this moment, I feel like there is so much hostility and aggression towards Mexican and Central American and Latino communities,” Rodriguez says. “This is a way of presenting these cultures. It’s incredibly important to present this type of other rich, cultural production, historic, material — this wealth of civilization.”

Some of the richness lies in the materials themselves — the centuries-old techniques that produce her colors, as well as the paper on which she paints: amate, a type of paper from Mexico handmade from the bark of the mulberry tree and various species of ficus. Amate was once employed by indigenous cultures in spiritual practice and for the creation of codices before the conquest. During colonization, the Spanish often burned works produced on amate, since they represented potent symbols of indigenous knowledge and faith.

“It’s outlaw paper,” says Rodriguez. “It was illegal at the time of the conquest.”

Curator Todd Wingate, who organized the exhibition at the Riverside Art Museum, says that Rodriguez’s materials are often what first draws a viewer into her work. “But there’s this whole other element that is so timely,” he says of the politics, “and she does it with such devastating grace.”

Three generations of painters

Certainly, painting is something that runs in the artist’s blood.

Rodriguez was born in San Diego to a clan of Mexican artists for whom painting represented both pleasure and craft. “I grew up with paintings all around the house,” she says. “Grandma’s house smelled like caldo de pollo [chicken soup] and oil painting.”

Her maternal grandmother created works that she sold at the family’s curio shop in Tijuana. Her maternal grandfather, who’d been adopted by a Catholic monsignor as a child, created religious imagery — some of it adapted from the work of Spanish Baroque painters such as Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.

“Growing up, around the house, there were always these ascending Virgins and dark paintings,” she says. “I thought they were my grandfather’s paintings, and all of a sudden I go to LACMA and there’s Murillo and I’m like, ‘Hey, that’s like from my house!’”

Rodriguez releases an infectious laugh, reddish curls grazing her polka dot dress.

Her family’s artistic traditions have other curious chapters too — like the time she went to art school with her mom, Guadalupe Rodriguez, who is also a painter.

It was 1993 and Rodriguez had enrolled as an undergraduate at California Institute of the Arts. Intrigued by what she was learning, she suggested her mom apply to the program.

“I went my first year and I said, ‘It’s a feminist art program, Mom — you’d love it!’” she recalls. “So picture 19-year-old Sandy with crazy hair and crazy outfits, [performance artist] Coco Fusco up front, and my mom in the back, playing with my hair.”

Her classmates at the time included now prominent painters such as Mark Bradford and Henry Taylor. “And my mom would be making birria by the loading dock and having tequila parties,” says Rodriguez, containing more laughs. “We are three generations of painters.”

She emerged from her studies in the ’90s at a time “when painting was a bad word” in the art world, she notes. “But I painted anyway. Painting is something I’ve always come back to.”

The spark of color

It was a family trip to Oaxaca, the southern Mexican region known for its centuries-old art and textile traditions, that served as a tipping point. At a bookstore, Rodriguez acquired a bottle of cochineal (cochinilla in Spanish), the brilliant red pigment whose use as a color dates back to the pre-Columbian era. Intrigued, she took the powder back to her studio, then in Leimert Park. (From 2014 to ’15, she was an artist-in-residence at Art + Practice, co-founded by Bradford.) But at first, she was unsure what to do with it.

Then Mexico erupted in protests after it was revealed that 43 students at a rural teachers college in Ayotzinapa likely had been abducted by police, turned over to gangsters and killed. Tens of thousands took to the streets at the end of 2014 in Mexico City, where protesters set fire to the door of the presidential palace and to an effigy of President Enrique Peña Nieto. As she saw the protests play out in the media, Rodriguez realized that she now had a use for the cochineal.

“The light came on,” she says. “That’s when I realized that color could have as much meaning as what I showed in the painting. ... It could be this specifically loaded material that could reference a history, a culture … it could stand in for mexicanidad and ruptures and all these ideas.”

She used the cochineal to create a series of canvases that depicted the fires that raged during the Ayotzinapa protests, as well as the infernos that regularly devastate California’s hills. The intensity of the reds in these works is practically visceral — as if it cannot be contained by the canvas.

Cochineal was just the beginning, however. “It was,” she says with a smile, “the gateway colorant.”

A Chicana codex

Further research led her to a book by Diana Magaloni Kerpel, “Colors of the New World: Artists, Materials, and the Creation of the Florentine Codex,” published by the Getty Research Institute in 2014.

Most color history texts focus on Western European traditions. Magaloni’s book tracks the history and meanings of tones employed in the Florentine Codex, the encyclopedic 16th century ethnographic study of colonial Mexico put together by Franciscan missionary Bernardino de Sahagún — a key colonial text that was written with the aid of indigenous scribes in Spanish, Latin and Nahuatl, the Aztec tongue. In it and other works of the era, color was often used as a way of subtly communicating information about an event.

“If you used cochinilla, which is translucent, you use it to describe elements of the terrestrial,” Rodriguez says . “Then there’s the iron oxide red that’s opaque — that communicates the underworld. It’s this coded use of color.”

Rodriguez began to study the history of natural pigments in both Mexico and the U.S. She went on medicinal plant hikes in the California desert. She learned what was edible and what functioned as tint. She began to chronicle the flora and fauna she encountered on amate paper — albeit with contemporary twists: Her painting of a prickly pear cactus (Opuntia basilaris), for example, features the ghostly outline of a helicopter whose profile is also a skull.

As she progressed, Rodriguez began to settle on the idea of creating her own codex.

“It was having all of these sketches from this area, and thinking about what makes California and each bioregion so rich and so interesting, and wanting to identify and remember where those medicinal plants came from.”

Plus, “it was thinking about the border and these artificial boundaries that have been placed, and trying to layer these narratives — it’s historic, it’s contemporary, it’s this precise political moment all in one. … I wanted to create a mestizo Chicana codex.”

In many panels, the artist includes representations of herself as a tlacuila — a scribe.

Looking back 500 years, she feels a distant affinity with the scribes who labored to create the Florentine Codex.

“There is a massive plague that happens at the end of the book,” she notes. “And they’re all dying, so they can’t go out and get color, and so everything is black and white. … They end up sequestering themselves so they can tell their story.”

“It was the end of the world,” she says ruefully. “That’s what it feels like now: the end of the world.”

“Sandy Rodriguez: Codex Rodriguez-Mondragón”

Where: Riverside Art Museum, 3425 Mission Inn Ave., Riverside

When: Through Jan. 27

Info: riversideartmuseum.org

“Here”

Where: Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, 4800 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood

When: Through Jan. 6

Info: lamag.org

ALSO

The best of times, the worst of times: art in the age of rising white supremacy

In advance of the midterms, Barbara Kruger reprises MOCA mural that asks ‘Who is beyond the law?’

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

carolina.miranda@latimes.com | Twitter: @cmonstah

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.