Writing ‘BlacKkKlansman’ was an exploration of ‘twoness’

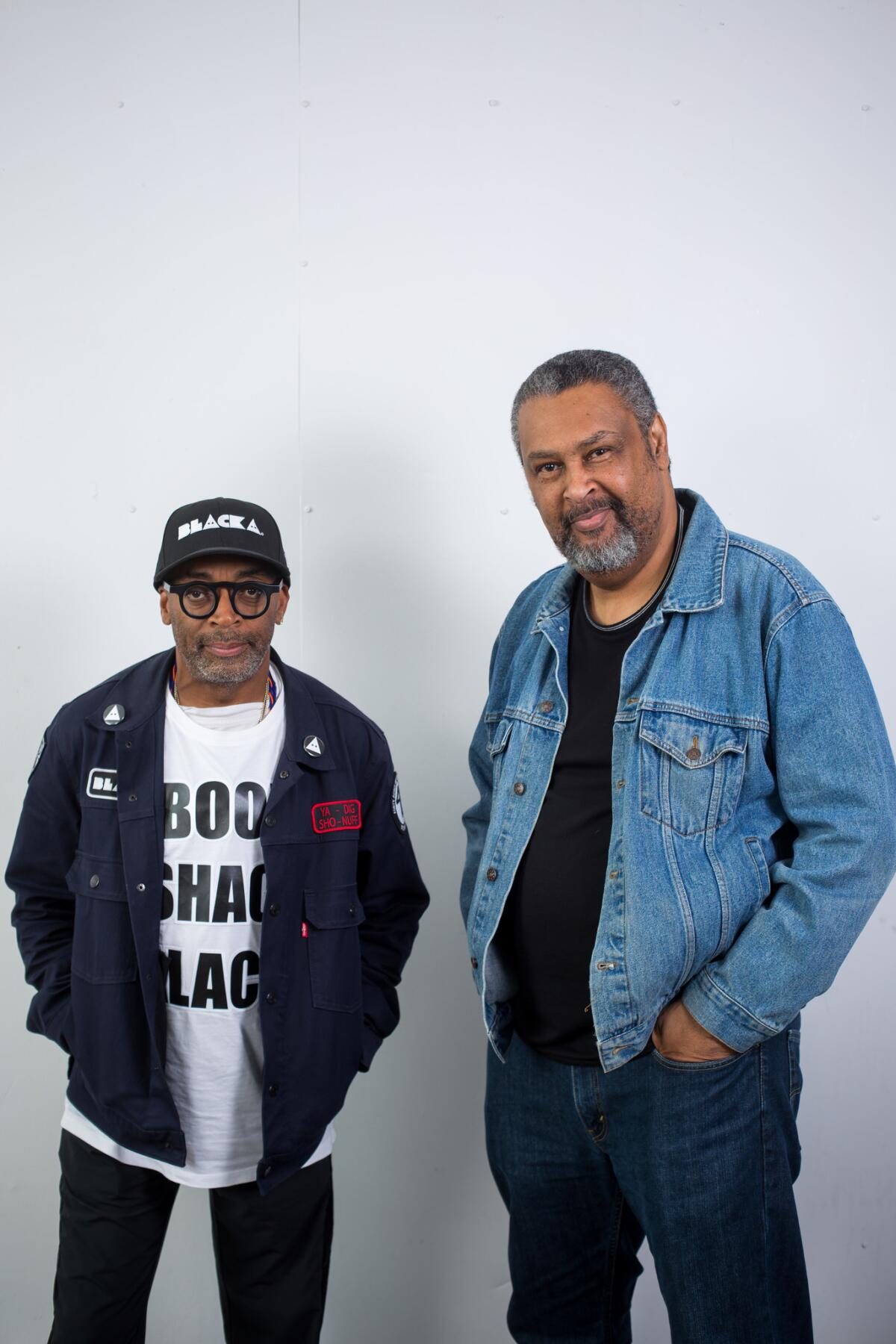

When Jordan Peele hired Spike Lee and me for this project, the only note he gave us was “make it funny.” We knew exactly what Jordan meant. He wasn’t speaking about broad comedy or jokes; he was instructing us to reveal the irrationality of racism. The more you expose the normality of hate, how it works historically, the more you locate the tentacles that touch us today. That is how you make dangerous subjects humorous. You don’t pull punches, you don’t censor words, you don’t make it acceptable; instead you get as close to the ugliness as you can and identify its absurdity. However, we did need one governing idea, a hook, to make the story cohesive.

We found that hook in a quote from W.E.B. Du Bois: “One ever feels his twoness — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength keeps it from being torn asunder.” Ron Stallworth’s book, “Black Klansman,” takes us into the procedural world of his investigation of the Klan in the 1970s. The rookie mistake that Ron, played by John David Washington, made of using his actual name over the phone with the KKK and subsequently having to create a “white Ron Stallworth” is the perfect illustration and metaphor of twoness. This became the major theme in “BlacKkKlansman.”

Spike wanted the film to resonate with the urgency of now. The past had to connect to today. We located in Ron’s book the current connection to our racial divide. Spike and I wanted our choices to not only speak to the political realities of the time but also the struggle of twoness in the characters. Ron’s relationship with Patrice, played by Laura Harrier, is complicated by her being a strong female activist patterned after human rights legends Angela Davis and Kathleen Cleaver.

When Ron hears the speech of Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), he finds himself connecting to his fiery rhetoric. Twoness is a condition that many black police officers voice today as a source of consternation. Ron’s issues with racism on the force was an opportunity to show how police need to police themselves. The ongoing deaths of unarmed young black men at the hands of police officers is a national tragedy. I have been in numerous screenings of the film where Landers, the racist cop, is arrested and the audience breaks out in applause because, unfortunately, this action remains a fantasy in American life.

We incorporated the issue of twoness into the narrative in numerous other ways: mistaken identity, the debate over imagery in “blaxploitation” films and the phone relationship Ron creates with David Duke. A surprising element of the film was discovering the twoness of being Jewish. Flip Zimmerman, a Jewish detective played by Adam Driver, is confronted by Ron and accused of “passing.” Flip has to go undercover as the “white Ron Stallworth” posing as a WASP. But in reality, Flip has been posing as a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant in real life.

Growing up in Kansas, I was often offered “honorary whiteness” by my white friends. A common occurrence when you are a person of color and “liked” is that you are offered assimilation into the majority group. Flip’s acceptance of “honorary whiteness” has disconnected him from his Jewish heritage. It is through going undercover as a Klan member and experiencing their barrage of anti-Semitic poison that he realizes he has lost an important part of himself.

Ron’s memoir gave us the launching pad to create a film about the past that exposes our present fight against the purveyors of hate. Jerome Turner, played by the legendary Harry Belafonte, tells the true story of Jesse Washington, who was tortured and lynched in 1915 in Waco, Texas. Washington’s lynching was fueled by the film “The Birth of a Nation.” Now, 102 years later, Spike uses the footage of Heather Heyer’s tragic murder in Charlottesville, Va., as a reminder of our present American nightmare. It is a call to end the hate that is currently being sold daily in the White House and from extremists throughout the country.

Our hope is that “BlacKkKlansman” is part of the prescription to heal the bitter divisions that continue to plague this nation.

ALSO

Review: Spike Lee at his peak, ‘BlacKkKlansman’ uses the past to explain where we are today

‘BlacKkKlansman’: Spike Lee’s urgent message about terrorism, truth and Donald Trump

What the star of ‘BlacKkKlansman’ learned from the real black cop who infiltrated the KKK

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.