Neil Leifer knows all the angles

January 6, 2008

NEW YORK -- For a guy who’s a regular at Elaine’s and has a standing reservation at Rao’s and his own gallery in Vegas and a new book out selling for $400, and now a short doc on Oscar’s short list, Neil Leifer still acts like he has something to prove.

Some of it’s the plight of the news or sports photographer, even if you’re the best. Leifer recalls how even Sports Illustrated sometimes sent him out with a snot-nosed reporter who’d introduce him by saying “This is my photographer.”

He tells too how one Time magazine writer would identify himself, even to natives in Africa, as “Joe Dokes” -- we’re changing the name -- “Harvard.” After which our hero would introduce himself as “Neil Leifer -- Seward Park High School.”

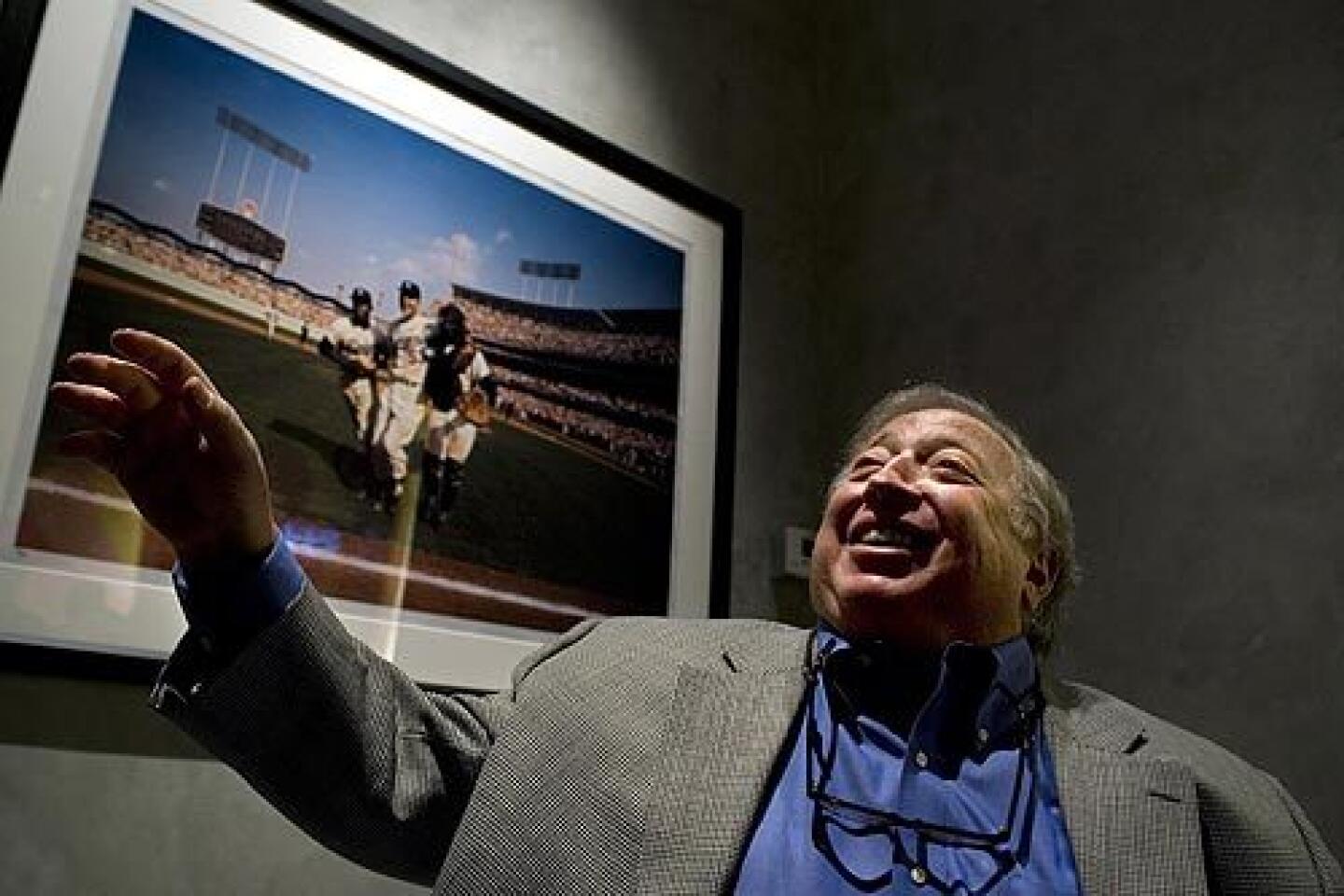

He embraces the persona of the guy from the streets who had to hustle his way to the top, the little guy -- 5-foot-6 at most -- who couldn’t rely on innate genius to get his famous shots. He had luck too, of course, as when he was in the perfect spot at ringside in Lewiston, Maine, May 25, 1965, to capture Muhammad Ali looming over a fallen Sonny Liston, a picture you can buy from him now for a mere $10,000. But he had to plot to get other landmark pictures, as when he dug a camera into the ground below second base at Dodger Stadium to snap Willie Davis sliding in, curving tiers of the ballpark looming behind him.

“What separates a really good photographer from the ordinary is, when things happen --when you get lucky -- you don’t miss,” Leifer says. “I didn’t miss.”

If he has an ego, it’s earned. But that record of not missing makes more frustrating what happened when he was primed to trade in his still camera for a moving one three decades ago, with dreams of being Francis Ford Coppola. Unfortunately, no “Godfather” has fallen his way since, leaving him to settle for self-financed shorts on a gossipy Korean nail salon or an arrogant baseball player who won’t sign autographs for anyone but babes with big boobs.

“My film career has not been the same success,” he sums it up one night in Elaine’s.

It’s not enough that he gets great tables there, or that he’s become one of New York’s classic characters at 65. There’s something else Neil Leifer wants now that will make everything right:

A nomination.

There’s one painting in his living room, a serigraph by LeRoy Neiman of the horse-racing themed 21 Club, with a personalized touch -- Neiman agreed to paint him into the scene.

Leifer naturally wanted “something dignified,” him in the back of a Rolls out front, being chauffeured by a nitwit editor of his. Neiman envisioned something less exalted: “He wanted to put him as one of the jockeys,” notes Leifer’s fiancée, Randye Stein, “because he’s short.”

Only one of Leifer’s own photos is in the room -- his shot from high up in the Astrodome looking down on Ali and an opponent, both with arms raised, except Ali is standing and Cleveland Williams is flat on the canvas. It’s a stunning visual, but also can serve as a Rorschach test, like his shot of Ali hovering over Liston: Is the lingering appeal the powerful man triumphant, or the one crushed to the ground?

“I would have to say vulnerability,” Leifer says. But later, out on the town, he tries again.

“It’s both,” he says then, triumph and defeat together.

MOST people have to wait for a near-death experience to see their lives flash before their eyes. He merely has to show up at Taschen bookstore in SoHo.

“You never sell books at these things,” he says at the party for “Ballet in the Dirt,” his oversized $400 volume of baseball photos. But no sooner does he sit at the signing table than the customers start coming up, credit cards in hand. “This is for my father, Al Silverman,” says the first, and Leifer says back: “He published the Ameche.”

Alan Ameche of the Baltimore Colts scored the winning touchdown against the New York Giants in the Dec. 28, 1958, NFL championship game that established football in the TV era. Leifer turned 16 that day and was on the field due to his typical . . . call it enterprise. The son of a postal worker and lingerie saleswoman, he grew up on the Lower East Side, where he took a photo class at a settlement house and learned how to sneak into Yankee Stadium, where the Giants played then. A group of wheelchair-bound veterans were allowed in free and if you waited at the right spot and volunteered to push ‘em in . . . and who was gonna check if you brought in a $75 Yashica-Mat camera?

The book buyer’s dad bought Leifer’s photo for a magazine previewing the next NFL season for about $100. Today it costs $4,000, that shot of Ameche pushing over the goal line with the Yankee Stadium stands behind him topped by flapping flags and gleaming lights, an archetypal warrior-in-the-arena image.

That was hardly the only time Leifer wrangled his way into a money shot. The cover of this book shows Dodger pitcher Don Drysdale celebrating a shutout in the ’63 World Series against the Yankees, the wrinkle being that Leifer -- then 20 and working for SI -- took the photo from the field, having hustled his then-skinny body (it sure ain’t today) out there while the last ball was in play. He insists he asked a guard, “ ‘If there’s an easy pop-up to the outfield, can I run out?’ But they tried to take my credentials away!”

Leifer says he didn’t see the capitalistic potential of such images until 10 years ago, when he convinced his brother, Howie, to quit teaching art in San Francisco and help market his photos through the tested formula of limited editions under which prices rise as more sell -- so buy now. Then the Neil Leifer Gallery opened at Caesars Palace in 2006, with the president of the Vegas hotel comparing his sports photography to “what Matthew Brady did for the Civil War era, and Ansel Adams did for the American landscape.”

Howie Leifer is at the signing too, unmistakably Neil’s brother, for not many people fit the description once affixed to a 1960s fullback, “Human Bowling Ball.” Also here is Pete Bonventre, Leifer’s best friend since Pete covered sports for Newsweek. In an evening of stories, Bonventre, now editor of Entertainment Weekly, offers the best, about “the line Coppola got from you,” as Leifer prods it out.

It seems Bonventre’s dad had as an uncle, Joe Bonanno, who headed a certain crime family. The story has Bonventre about to go to college, so Uncle Joe asks, “Do you mind if I give Peter some advice?”

The advice was a nugget Bonventre later passed to a friend before she saw Coppola as he was making his movie on the mob: “Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer.”

Bonventre adds, “Years later, someone said -- who wrote ‘The Art of War’? The Chinese guy -- that [Bonanno] may have stolen it from that.” But this is the Leifer saga, not the Corleone saga, so the relevant fact is that his buddy arranged for him to photograph Uncle Joe and then he landed at Bonanno’s 95th birthday in Tucson, sitting with Pete’s mom, by the dais.

It was Pete too who helped prompt his leap into the movies.

THIS tale comes out at Elaine’s, up on 2nd Avenue, where movie people hang, and the literary crowd, and Leifer. Indeed, he’s seated at the table where he put two characters in “God’s Gift,” the short about the arrogant ballplayer. This night’s crowd includes a fellow writing his next effort, about two old Red Sox fans who want their ashes scattered at Fenway Park.

Leifer got the movie bug when offered freelance jobs on sets -- people who made sports films would pay big to have a sports photog like him shoot their make-believe games. He was hired on 1974’s “The Longest Yard,” 1975’s “Rollerball” and some of Sly Stallone’s “Rocky” pictures, which got him thinking how photographers Stanley Kubrick and Gordon Parks had segued into directing films.

He and Bonventre were driving to a fight and Leifer said, “ ‘Haven’t you always wanted to write one?’ ” the magazine editor recalls. So Bonventre penned a script based on the Falco brothers, with whom Leifer had grown up, one a dancer, the other a cop killer. While that didn’t sell, Leifer, as if by magic, got a call from producer Elliott Kastner (1966’s “Harper”), who’d seen his photos and “decided I had a passion and gave me a Jackie Collins script.” The 1979 film “Yesterday’s Hero” was about an English soccer star who has become a drunk but dries out and leads his team to triumph with the inspiration of Suzanne Somers. Problem was, it was filmed in London and Leifer had a wife and two kids on Long Island. “My wife . . . thought I had lost my mind,” and that was the end of the marriage, “but I directed a feature.”

He saw himself destined for Hollywood, “and in my wildest dreams I would have liked to have been Sidney Lumet or Francis Coppola,” but the soccer film went nowhere, and he did not get another until “Trading Hearts,” a 1987 baseball romance with Raul Julia and Beverly D’Angelo. After that, there was no Offer 3.

That’s when “I started to do the short films,” he says, on which he, no one else, was the boss. The first, “A Neil Leifer Film,” was 1991’s “Rosebud,” featuring simultaneous gossip by Korean manicurists and their American customers -- about the same paramour, it turns out. Bonventre wrote another, “Small-Room Dancing,” inspired by his son’s society-style ballroom classes in suburban Bronxville. Leifer made “Scout’s Honor” too, in which Bill Murray and Alec Baldwin play basketball scouts at -- in another twist end -- a game among 10-year-olds.

Leifer learned he could get such stars -- for one day’s work, at least -- simply by asking, and “get ‘em to work for free.”

One geezer in his baseball short will be Dominic Chianese, “The Sopranos’ ” Uncle Junior. And at Elaine’s, he calls to the next table, “You’re going to be in the Red Sox film!” It’s crooner Steve Tyrell, at the moment garnering $130 covers playing Cafe Carlyle. “I draw the line,” says Tyrell, whose own fans include the Steinbrenner clan. “If I was a Sox fan I’d be banned from Yankee Stadium. George’d never let me in his box.”

Leifer’s photo sales enable him to finance his films, but it’s not all vanity -- in back of his mind is the hope that his shorts will be bought and expanded. That happened with “The Great White Hype,” a 1996 takeoff on boxing in which a pale challenger is built up only to be conked with one punch. Produced by sports movie auteur Ron Shelton (“Bull Durham” “White Men Can’t Jump”), it then was sold as a feature, just not with Leifer as director. “I wish they had let me,” he says. “They chose not to.”

But he pushes on, both for the fun of it and for something he experienced with his first short, about the nail salon. It got “shortlisted” for an Academy Award nomination in 1992. The category was obscure, live-action short film, and it never got a nomination, but the listing was enough.

“I said to myself, ‘By the time I’m 60, I’m going to have three or four Oscars.’ That hooked me. I keep making them thinking it would happen again.”

Walter Bernard, who had the idea that became Leifer’s “Portraits of a Lady,” has a nickname for him , “The Pest,” because he’ll call six times to confirm you’re meeting for dinner.

The former art director of Time, Bernard is among a group of portrait artists who meet in Manhattan. He thought it might be interesting to use a “prominent American” as a model to document how 25 sets of eyes see different things in a person.

The Pest “loved the idea,” Bernard says, and they soon had HBO intrigued with their proposed model, Bill Clinton, the only hitch being Clinton. When he said no, so did HBO.

Bernard rented out his home in the Hamptons to pay his share of filming the artists painting the model they did enlist, former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. Then they tried HBO again, sending over a “teaser.” Once more, no sale.

Another channel did offer “$50,000 less than the ultimate cost of the film,” Leifer says. “We said, ‘We’re not going to pay for the privilege of putting it on your network.’ ”

So they completed the thing on their own dime, sent it again to HBO, and this time got back an e-mail: “Come to a meeting.”

Sheila Nevins, HBO’s czar of documentaries, says she had no choice. “Neil would have hounded me to my grave.”

It was an odd fit, for Nevins is known to embrace dark visions and naked women, and this had neither. “Anything that’s tragic, I’m for,” she quips. “Sad is better than happy.” But she rationalizes that there was a “sweet sadness” to how O’Connor was out of a job now, and how some of the artists “don’t paint as well as they used to. There’s no human suffering, but one of them is going blind,” she notes, “and I made Neil suffer too.”

Her reward was dinner at Rao’s, the East Harlem hole in the wall. Owner Frankie Pellegrino is known as “Frankie No” because that’s what he says when people call for reservations. The tables are taken by regulars such as Sonny Grasso, the “French Connection” cop turned producer, and Bo Dietl, the private eye. And Leifer. Nevins joined him and his fiancée, an environmental lawyer, on the night Frankie announced monthly dates for the year to follow, “and there was a hushed silence,” Nevins says. “ ‘Are we going to get the third Tuesday?’ ”

Pellegrino has had a sideline as an actor since Martin Scorsese gave him a part in “GoodFellas.” He’s appeared in virtually all Leifer’s films too, and in the Red Sox short will be the friend who totes Uncle Junior’s ashes to Fenway. “Anything Neil wants,” he says.

Nevins can do a routine of one-liners on Leifer: He’s “someone you can’t get your arms around but you’d like to hug . . . . Your fingers can’t meet on the other side.” Or “he’s got get up and go -- I don’t know if he can get up, but he sure can go.” Oh, and “He’s really a right-winger -- he voted for Bush. Why did I buy his film? He told me afterward.”

Nevins does have one question, though. “Is Neil rich?”

HE says, “Yes,” in the sense that if he wakes up and wants to fly somewhere, he can afford to -- even with his restaurant tabs.

It’s another night at Elaine’s and he’s fretting about the Oscar nomination announcement on Jan. 22. He can guess “the kind of films they vote for and mine is not -- dark films.” He guesses too that “nobody cares about the short docs,” but he does, and that’s why he kept “Portraits of a Lady” to 40 minutes and arranged a qualifying theater run in L.A., no matter that “six to eight” people came to each viewing.

“I want to get nominated for an Academy Award,” he says. “That’s what I want.”

The list of eight contenders includes “Freeheld,” about a lesbian policewoman dying of cancer, desperate to get benefits for her partner; “Salim Baba,” about an Indian man who screens film scraps for kids; and “Sari’s Mother,” about an Iraqi seeking help for her 10-year-old with AIDS . . . all about humanity on the canvas, as in his legendary boxing photos.

He’s attended the Academy Awards a couple of times, with Bonventre and with a date, driving a rental Honda amid the limos. It was like a dream, marching along the red carpet with the beautiful people, “and as you approach the sea of photographers . . . they’re shouting, ‘Tom!’ ‘Arnold!’ ‘Nicole!’ And down the aisle come the nobodies like me.”

The twist that time was that he was hardly a nobody to those photographers. “I grew up with every one,” he says, “so they’re shouting, ‘That’s Leifer. Hey, Leifer! Leifer!’ ”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.