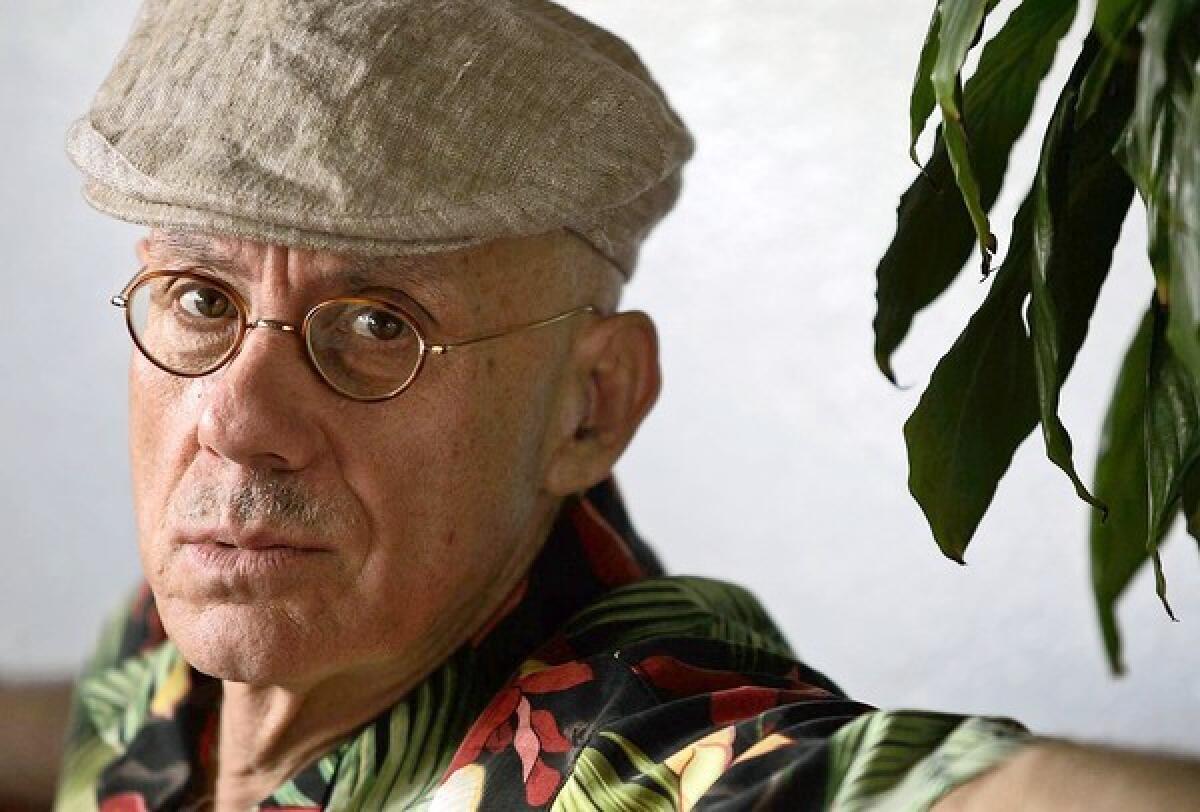

Book review: ‘The Hilliker Curse: My Pursuit of Women’ by James Ellroy

At some point, many bookish people find themselves struck by the first stanza of Philip Larkin’s mordant, post-therapy poem “This Be The Verse”:

They … you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

Now, most readers of a certain maturity get over it and move on to discover Larkin’s true masterpieces: “The Explosion” or those unflinchingly disappointed wonders “Maturity,” “Marriage” and “Under a splendid chestnut tree.” Some, however, never do and remain transfixed by childhood’s trauma, their original pain preserved like some ancient insect in emotional amber. Among the latter is the now 62-year-old James Ellroy, whose first volume of memoirs, “My Dark Places,” now is joined by a second, “The Hilliker Curse: My Pursuit of Women.”

Ellroy is one of the most compelling of our contemporary crime fiction writers. His L.A. Quartet (“The Black Dahlia”, “The Big Nowhere,” “L.A. Confidential” and “White Jazz”) and his Underworld USA Trilogy (“American Tabloid,” “The Cold Six Thousand” and “Blood’s a Rover”) are masterful explorations of the noir genre that cross the boundary dividing mere entertainment from literature. They’re books that owe something to Ellroy’s expressed admiration for Hammett and Chandler and, stylistically, far more to the unacknowledged influence of Kerouac’s bop prosody. Fans of his fiction and, particularly, of his first volume of memoirs will know that the animating events of his life and writing career are childhood tragedy and a sleazy adolescence on L.A.’s streets that included drug and alcohol abuse, petty crime, jail time and voyeurism.

The tragedy occurred at age 10. Ellroy’s parents — a nurse and accountant — were divorced and he was living with his alcoholic mother in an El Monte apartment. One day she asked him whether he wanted to go on living with her or his father:

“I said, My dad.

“She hit me.

“I fell off the couch and gouged my head on a glass coffee table. Blood burst out of the cut. I called her a drunk and a whore. She knelt down and hit me again. A shutter stop blinked for her. She covered her mouth and pulled away from it all.

“Blood trickled into my mouth.... I issued The Curse, I summoned her dead. She was murdered three months later. She died at the apex of my hatred and equally burning lust.”

Ellroy has been drinking from that cup of Oedipal guilt, rage and obsession ever since. It’s made for a fascinating body of fiction and compellingly written, but emotionally tedious, memoirs. In “My Dark Places,” he recounts his mother’s murder and his own subsequent attempts not only to come to terms with it, but also to solve it. “The Hilliker Curse” — the title incorporates her maiden name — is an account of her death’s influence on his relationships with women, including two marriages that ended in divorce and the feverishly described liaison in which he’s now engaged. What to make of it all is a bit of a muddle.

As a writer, Ellroy is never less than entertaining, even when his manic side is at its most grating. As a memoirist, he’s a complicated case. In the first instance, there’s the problem of his public persona, which is theatrical, exaggerated and — by his own admission — calculated to provoke with a whole variety of unfashionable political and social views. Where the consciously constructed James Ellroy and the real James Ellroy intersect is a location he sometimes finds hard to identify. Take, for example, this account of a 2004 reading in Sacramento that the author describes in “The Hilliker Curse” as “the six thousandth public performance of my dead mother act.” A standard introduction to one of his readings goes like this:

“Good evening peepers, prowlers, pederasts, panty-sniffers, punks and pimps. I’m James Ellroy, the demon dog, the foul owl with the death growl, the white knight of the far right.… I’m the author of 16 books. Masterpieces all; they precede all my future masterpieces. These books will leave you reamed, steamed and dry-cleaned, tie-dyed, swept to the side, true-blued, tattooed… These book are for the whole …family, if the name of your family is the Manson family.”

Very funny, a terrific riff and not informative in any fashion that makes for a trustworthy memoir. The standards for a novelist making material of their lives simply are different from those for a memoirist, and there’s no clear sign here that the author respects the difference — or anything, for that matter, but his own needs and impulse. The real problem has to do with what one suspects he’s being most sincere about — his attitudes toward women. Here, Ellroy resembles one of the people whom psychotherapists sometimes describe as those who collect “insights as excuse.” In other words, they fasten on reflective bits from their past as a way of explaining and excusing their current behavior and not as potentially transformational experiences. Everything is explained, and everything remains the same.

Ellroy’s attitudes toward women — whether the Sunset Boulevard hookers in whose rooms he wept or his wives — fall pretty firmly into that category. It may come tricked up in all sorts of jazzy language, but it’s all about mom. The best you can say is that there’s an irremediable confusion here between obsession and love. However he meets them and however rhapsodic the prose, whether prostitute, quick hit or spouse, the women in “The Hilliker Curse” exist mainly as emotional spackle to fill the cracks and holes in Ellroy’s ravaged but grandiose psyche.

Take, for example, this description of the beginnings of his current relationship: “We were attempting to merge into a symbiotic and non-codependent whole — whatever the parameters of our union.… It eclipsed sexual conjunction and anointed us with a solar system-high calling. We had to become the best parts of each other. I had to learn tolerance and greater humility. Erika required a transfusion of my determination and drive. I believed it because I knew it to be real beyond all manifestations of madness in my woman-mad life to date. Erika considered us cosmic.” Whatever can that mean?

He watches her emerge from the shower to dry her hair and is struck by her resemblance to the murdered Jean Hilliker.

It’s still all about mom.

timothy.rutten@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.