‘The Woman in Black’ review: Eerie doings in Victorian England

Doors creak, birds shriek and children are lured to terrible fates in “The Woman in Black,” a good, old-fashioned ghost yarn of the Victorian Gothic persuasion.

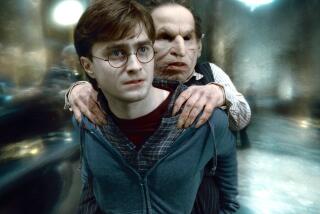

The handsome chiller, set in an atmospherically isolated Yorkshire village, is a production of England’s revived Hammer label and features Daniel Radcliffe in his first post-”Harry Potter” screen role. He plays a character who, not unlike Harry, takes a train to an otherworldly place where he faces down immense forces of evil — albeit without the wizardly magic, and with an occasional fortifying shot of whiskey.

Radcliffe’s limitations as an actor are suited to the role of mild-mannered attorney Arthur Kipps, a widower with a young boy. When we first see him, he’s a man between life and death, a fact that doesn’t change until the film’s poetic resolution. Even as Kipps becomes actively engaged in solving the story’s mystery, he’s a strangely somnambulant figure, less determined than fevered.

On a last-chance assignment to save his career, he’s dispatched from smoky 19th century London to the remote northern hamlet of Crythin Gifford (set in the no less lyrically named Halton Gill) to settle the estate of a deceased recluse.

In a place with nary a telephone and a surfeit of guarded villagers, Kipps pieces together a local history of devastating losses. The latest in a long line of children to die does so in his arms, and his own grief makes him particularly sensitive to a vengeful spirit in mourning black (Liz White) who appears to him at his client’s house.

Like an island unto itself, that house lies at the end of a causeway through marshes and is often separated from the village by high tides. A great symmetrical pile with its own graveyard, it’s the film’s most expressive character — as it should be — thanks to the outstanding production design by Kave Quinn and Tim Maurice-Jones’ fluent widescreen camera work.

It’s also the setting for a few too many manufactured shocks punctuating the early stretches. But though the film can work simply as a haunted-house thrill ride, director James Watkins (“Eden Lake”) is building a deeper unease and ultimately doesn’t cheat the morbid heart of the narrative for the sake of excitement.

If the story is laid out none too subtly, its straightforward purity is, finally, its greatest strength. Screenwriter Jane Goldman has adapted Susan Hill’s 1983 novel (which spawned a radio series, TV movie and long-running West End stage play) with economy, placing a premium on eeriness, not gore.

Setting the tone is the concise and doomy beauty of the opening scene, involving three young sisters. The unsettling images of childhood vulnerability have added resonance in the Victorian setting, given the period’s growing interest in the consciousness and welfare of children. Watkins’ visual vocabulary grows smaller as the film progresses, but even as the repetition feels self-conscious (especially in a nursery full of watchful toys), the foreboding mounts.

Late in the proceedings, a handprint on a window and the rapid rocking of an unoccupied chair deliver true jolts and chills, visions of the in-between world that the story, and its despondent protagonist, occupy.

The uncertainty of Radcliffe’s performance mostly serves the character well. He receives unerring support from Ciarán Hinds and Janet McTeer, as a well-to-do couple on opposite sides of the skepticism/belief divide. Hinds’ insistently rational Sam Daily dismisses his neighbors’ superstitions and warns Kipps not to chase shadows.

But Kipps is inescapably drawn to dark places, locked rooms and, in a remarkable sequence, straight into the black muck of the marsh. With that unspeakable plunge, he shakes off sleep to face his nightmare.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.