UCLA fest looks at writers and directors from TV’s golden age who transitioned to movies

It’s a time when television is all the rage, when what’s being done on the small screen is the envy of Hollywood. It’s a time like today, only it’s not.

That time was the 1950s, when anthology shows like “Playhouse 90,” “Studio One,” “The Elgin Hour” and “Goodyear Television Playhouse” ran original dramas that were broadcast live and offered adult-themed stories laced with reality, integrity and relevance.

For the record:

1:27 a.m. Nov. 25, 2024An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that actress Lee Remick appeared in the film “Tomorrow.” The second film in the series she stars in is “Baby the Rain Must Fall.”

But while today’s movie studios, owned by conglomerates and intoxicated by the lure of superhero tent poles, put their collective heads in the sand and allow network and cable to walk off with the adult audience, Hollywood back in the day was more proactive.

Simply put, the studios co-opted the cream of the small-screen talent, hiring top writers like Paddy Chayefsky, Reginald Rose, Rod Serling and Gore Vidal to create theatrical features. Producers even remade the best of these television dramas for theatrical distribution.

This fascinating turn of affairs, which led to any number of terrific films, many all but forgotten today, is detailed in the absorbing UCLA Film & Television Archive series “Golden Age Television Writers on the Big Screen,” starting on Friday with a screening of the prescient satire “Network,” written by Chayefsky and directed by Sidney Lumet.

Lumet (whose classic jury room drama “12 Angry Men,” scripted by Rose, screens on Aug. 20) was a golden age veteran, and the series also shines a spotlight on directors like himself and Delbert Mann (an Oscar winner for “Marty,” who has three films in the series), who were able to flourish on screens of all sizes.

As a side benefit, “Golden Age Television Writers” highlights splendid actors who have fallen out of the public conversation. Like Lee Remick, memorable in both “Days of Wine and Roses” and “Baby the Rain Must Fall,” and the underappreciated Don Murray, who will be present on July 28 for a double bill of “The Bachelor Party” and “Baby the Rain Must Fall.”

On view as well are two of John Cassavetes’ first big-screen appearances (“Crime in the Streets,” “Edge of the City”) and two films each for Robert Duvall (“Network” and “Tomorrow”) and Fredric March (“Seven Days in May” and “Middle of the Night”), productions that showcase the range of these men’s work.

The main emphasis of the series, however, remains on the writers, and the best of their work falls into two categories, both of which the studios now scorn: stories with broad political and societal themes, and small-scale intimate dramas that reveal the unsung poetry and humanity of ordinary lives.

The single writer able to convincingly do both was Chayefsky, the only individual to win three screenplay Oscars (for “Marty” and “Hospital” as well as “Network”) without a co-writer.

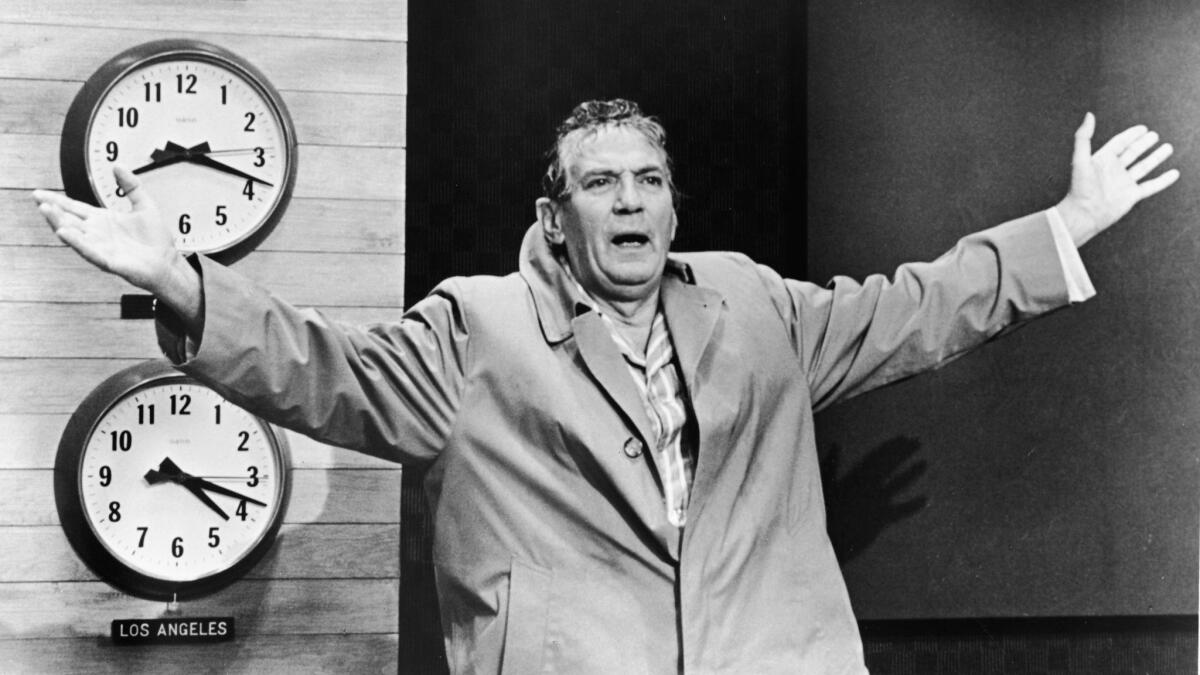

Though “Network” came out in 1976, that savage jeremiad, describing an amoral television world where literally anything, even the taking of human life, is allowable in the name of preserving ratings, feels more frighteningly contemporary now than when it came out.

For who can hear the words of Faye Dunaway’s television executive proclaiming “the American people are turning sullen” and “the American people want somebody to articulate their rage,” and not think of the 2016 presidential campaign. When Peter Finch’s network anchor screams, “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore,” his words echo as they never have before.

Also politically incisive are the Saturday 1964 double bill of “The Best Man,” adapted by Vidal from his play and directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, and “Seven Days in May,” adapted bySerling from a bestselling novel and directed by John Frankenheimer.

Vidal is very much in his element in his story of a bare-knuckles political battle for the Democratic presidential nomination between Henry Fonda’s patrician intellectual and Cliff Robertson as a conservative rabble-rouser who wants to simultaneously cut taxes and increase defense spending. Some ideas never die.

“Seven Days in May,” with its emphasis on public patriotism and private treason and what one character slams as “whispers we have somehow lost our greatness,” also has its contemporary relevance, but there is more here as well.

There is a crackerjack plot of a high-ranking group of officers planning a military coup and fine supporting work from Ava Gardner and March, but best of all there is the unbeatable duo of Burt Lancaster as chairman of the joint chiefs of staff and Kirk Douglas as his tip-top No. 2. Masculine presence doesn’t get any more masculine than this.

One of the stars of the series’ other thrust, the character-based drama, is Horton Foote whose screenplays for “Baby the Rain Must Fall” and “Tomorrow” were based on his own plays. Frequent star Duvall called him “the rural Chekov.”

Shot in Foote’s home town of Wharton, Texas, and directed by Robert Mulligan, “Baby the Rain Must Fall” is powered by a burning performance by Steve McQueen as a would-be rockabilly sensation whose troubled past won’t let him go.

Pride of place in the series, however, goes to Chayefsky, who died in 1981 at age 58. In addition to “Network,” three of his intimate dramas are featured, and taken together they are a revelation, highlighting a style of filmmaking that has close to disappeared.

Least known of the group is “Middle of the Night,” starring March and Kim Novak as age-inappropriate lovers, while the unlikeliest family grouping would have to be “The Catered Affair,” written by Vidal from a Chayefsky play. Bette Davis, Ernest Borgnine and Debbie Reynolds play a working-class Bronx family thrown into emotional chaos when the daughter declares she wants to marry without a fancy catered event.

The most affecting of the trio would have to be the Delbert Mann-directed “The Bachelor Party,” which depicts the strains an unexpected pregnancy puts on a young marriage, with Murray’s bookkeeper and his co-workers going through a long night of the soul during a rowdy bachelor event.

Some things have dated since Chayefsky’s heyday; phones are no longer dial-up and a $68 doctor bill for a house call is no longer considered extravagant. But even if storytelling like this has gone out of style, the emotions depicted can still tear you apart.

“Golden Age Television Writers on the Big Screen”

When: July 7-Aug. 20

Where: Billy Wilder Theater, Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

Tickets: General admission, $9

Info: (310) 206-8013, www.cinema.ucla.edu.

All screenings at 7:30 except as noted.

July 7: “Network”

July 8: “The Best Man,” “Seven Days in May”

July 14: “ Dear Heart,” “The Catered Affair”

July 16 at 7 p.m.: “Middle of the Night”

July 22: “Days of Wine and Roses,” “Crime in the Streets”

July 28: “The Bachelor Party,” “Baby the Rain Must Fall”

July 30 at 7 p.m.: “Up the Down Staircase”

Aug. 6 at 7 p.m.: “Tomorrow”

Aug. 11: “The Lost Man,” “Edge of the City”

Aug. 20 at 7 p.m.: “12 Angry Men”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.