Q&A: Director Nancy Buirski on the lessons of ‘The Rape of Recy Taylor’ and the courage it takes to speak out

On Recy Taylor’s way home from church one night in Abbeville, Ala., a group of white men accosted her on the street. They forced the 24-year-old wife and mother into their truck and six of them took turns raping her. This was in 1944 and though the incident was reported to police immediately, the assailants were never brought to justice.

Nearly 70 years later in 2011, the state of Alabama issued an apology to Taylor for not prosecuting her attackers. She was 91 years old.

"It is apparent that the system failed you...," said Henry County Probate Judge Jo Ann Smith to several of Taylor's relatives at a news conference at the county courthouse in March of that year.

This real-life miscarriage of justice, brought about by racism, is the foundational point of Nancy Buirski’s documentary “The Rape of Recy Taylor,” playing at Santa Monica’s Laemmle. She hopes the film, which will open in New York Dec. 15, will prompt “a total cultural and sociological change.”

“I hope it raises the consciousness of a lot of people and drives more of a reckoning beyond the apology,” she said.

Recy Taylor spoke up in 1944 when her life was in danger. Now, we really can appreciate how courageous that was...

— Nancy Buirski

Inspired by Danielle L. McGuire’s 2011 book “At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape and Resistance — A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power,” “The Rape of Recy Taylor” chronicles the fateful night of Taylor’s attack and the resulting investigation by authorities. Through interviews with members of Taylor’s family as well as academics, the film charts how Taylor’s story became national news and was a spark for the eventual Civil Rights Movement.

Ahead of the film’s opening, The Times spoke with Buirski — who’s also made docs on ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq and famed director Sidney Lumet — by phone about making a doc about Recy Taylor, how civil rights icon Rosa Parks got involved and what’s to be learned from the picture at a time when sexual assault and harassment occupy headlines.

How did you come to Recy Taylor’s story?

I was working on another project that fell through and a producer on that told me to check out Danielle McGuire’s book “At the Dark End of the Street” which [deals] in the very beginning with Recy Taylor’s story and the involvement of Rosa Parks. We often say in the industry that when bad things happen, good things often come from it. This is a perfect example of it… This was so much more interesting, and so much more important [than what I was working on]. I didn’t know about the staggering amount of rapes that had taken place during that period. I knew about lynching but I didn’t know this was taking place in the Deep South and women were constantly being molested. Obviously, very few women would speak up, but Recy Taylor did. There was something so substantial there. To be able to reveal this story on film, it just felt like something I had to do.

What surprised you most about it?

I realized very soon after discovering the story that I shouldn't have been surprised. The minute I connected the way African American women were treated during slavery on plantations — how they were owned as property and how I always knew that white masters felt entitled to sleep with or rape these women — with the fact that this continued as a mentality, I realized I shouldn’t have been surprised. I just didn’t have the evidence in front of me, so I was struck by the knowledge of what had happened.

The fact that Recy had the courage to speak up is mind-boggling given the danger she was in, that she was in fear for her life and her family’s safety, but she immediately spoke up.

I also realized, about the time period, that African American women had been talking about this happening in their families for generations. They know by looking at their skin colors that it’s a legacy they live with.

The film notes that this story only became national news because of the black press.

It was essential. If not for the black press, I’m not sure the story would’ve ever gotten out there. The white press just wasn’t paying attention to it, and rarely did. The black press felt a responsibility to portray black life as it was really being lived. The women who organized the Committee for Equal Justice for the Rights of Mrs. Recy Taylor understood that they needed to use this as a tool to get the story out. They could get as many people as possible to write letters to the governor and send telegrams and rally, but if it wasn’t in the press, there was, as a scholar says in our documentary, plausible deniability. If the press doesn’t write about it, then well maybe it didn’t happen. So the black press put pressure on the white press and once the white press starts to write about it, then the governor really has to do something.

While most know Rosa Parks as the woman who, too tired from a long day of work, refused to give up her seat on a bus, you reveal in the film her storied activism. Talk about that decision.

The fact that she was an activist for so many years [before the Montgomery Bus Boycott] is an important reveal in our film. I think it's also interesting to understand why this story has played out the way it has. Rosa Parks is an icon and considered the mother of the civil rights movement, but how did that happen? That’s not just by coincidence. There was a concerted effort to position her that way.

She was a respectable, relatively light-skinned black woman who gets arrested after refusing to get out of her seat. She wasn’t planted on the bus ... but she wasn’t afraid to be arrested. Once she refused to move her seat, people rallied around her and said, “This is the symbol we needed all along.”

There’s such a thing in scholarship around African American studies called “politics of respectability ...” She fit [that idea] so they rallied around her and called on Martin Luther King Jr. to be the spokesperson. It came together that way and they were careful … to create the proper showcase. That’s the legacy she took on. Whatever else she had done before they didn’t feel it was part of the story. It wasn’t as good a story. The story of a tired seamstress refusing to move her seat is a much better story than an activist taking advantage of a situation.

Rosa Parks fended off an attack herself when she was a teenager. She tried to register to vote three times and was turned down twice. She was actively involved in trying to change her people's story for quite a long time and then she goes to work for the NAACP as a secretary in 1943. By 1944 when Recy Taylor is raped, she’s taken on the role as investigator as well. She was an activist for at least 11 years before the bus boycott.

Why did you use scenes from what were then called “race films” from filmmakers like Oscar Micheaux to depict Taylor’s story?

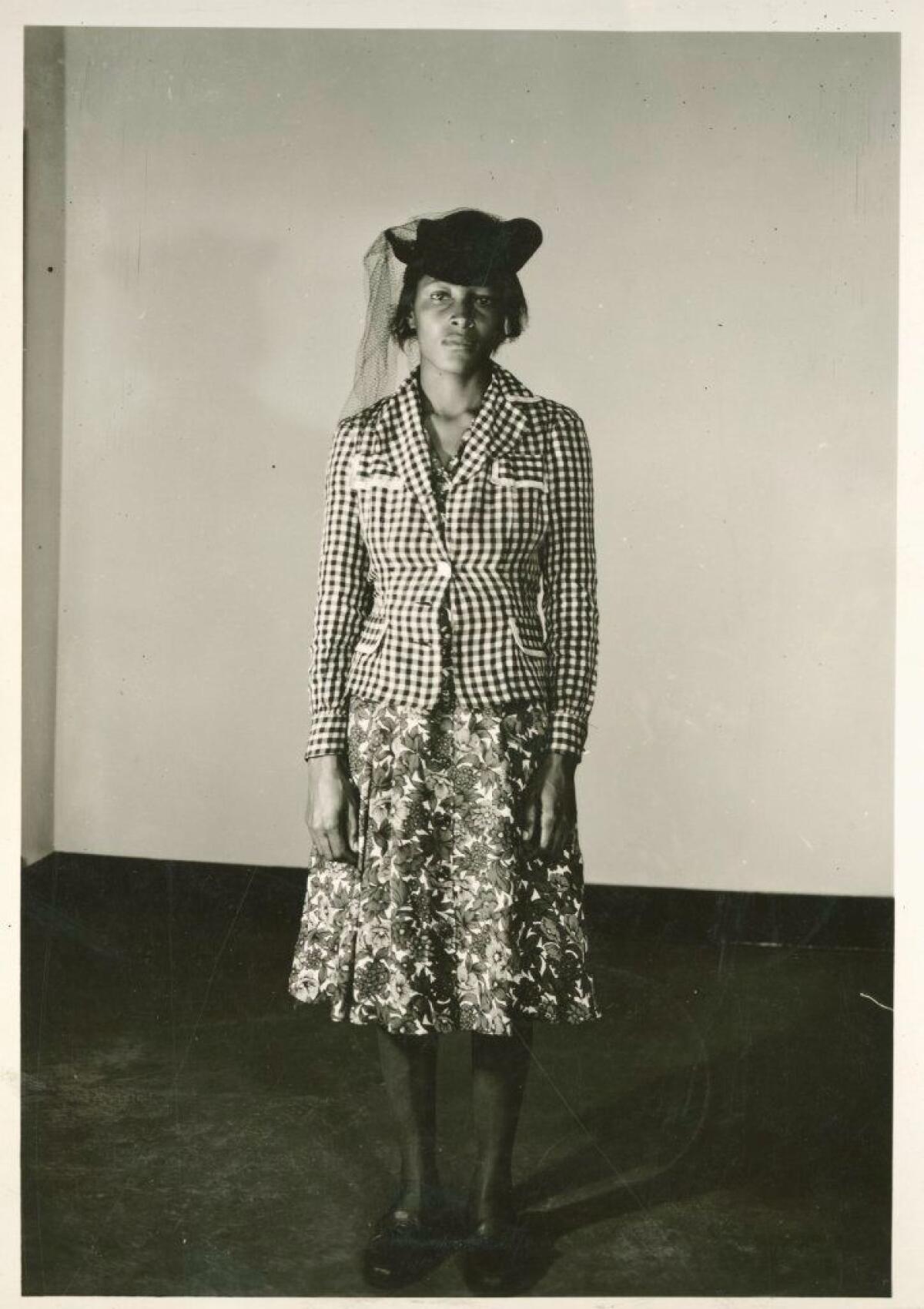

One of the challenges in making this movie was that I wanted to tell Recy Taylor’s story, to convey the emotion and drama and import of that story and make it as intimate as I could, but I also wanted to tell a bigger story and make it clear that what happened to Mrs. Taylor happened to many other black women during that period. Other than having a scholar say that, I felt that using these almost mythical-looking images of women from these films would make that point. There’s an aesthetic that goes with these movies that makes it feel classical, almost biblical. That’s just a gut creative feeling I had when I looked at them, that they could represent a population, a community, a group of women that'd be hard to represent any other way.

It’s an intellectually sound idea I thought, because these were also films that, even though they were fiction, were making an effort to represent black life in a non-stereotypical way unlike the mainstream movies that people were seeing those days where blacks were caricatured as mammies or jezebels or Stepin Fetchit-type characters. When blacks looked at these films, they saw things a little more realistic. I thought that was integral to the story I was trying to tell, which is how black people were represented in those days and why it was so hard for them to get justice.

You’re a white woman directing a movie about racism and the rape of a black woman. How do you think your identity impacted your approach to the film?

My first film, “The Loving Story,” deals with some of the very same issues we're dealing with here in “The Rape of Recy Taylor” and that was turned into “Loving,” which I produced. The question is a fair one and I’ve given it a lot of thought because of the responsibility when you take on a film about a community that isn’t yours. Number one, I feel like these stories are the American legacy and whites are responsible for what we often consider the American original sin which is slavery. So, I feel a responsibility as a filmmaker to deal with the issues most palpable to our times. It feels like this is as serious an issue our country has ever faced. I feel a responsibility and almost complicit if I were not to approach it in some way.

That said, I could never tell this story the way a black woman would tell it. I know that. I’ve never been in a black woman’s skin and I don’t try to represent myself that way. I’m hoping that by my putting this story out there — and it happens to be the first time it’s been told on film — more people will tell it, including black women, and they will tell it from their perspectives.

What do you think there is to be learned from the film as it relates to the current instances of sexual assault and harassment overtaking headlines?

The first one that comes to mind is that Recy Taylor spoke up in 1944 when her life was in danger. Now, we really can appreciate how courageous that was when we realize how hard it is for women of more privilege, mostly white women, who are speaking up now when what’s at risk is their careers. And I’m not trivializing that at all. It’s still courageous for them to speak up, but I think it shines a light on how brave Recy Taylor was.

I also think it tells us a lot about men and society and how so many men in those days protected their own. One of the reasons the boys weren't indicted is that so many of the people on those juries would’ve probably done the same thing.

But I think it’s a great time for a reckoning on all of this. Men have to come to understand what their instincts are and what their responsibilities are to control those instincts and women need to feel more empowered to speak up.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.