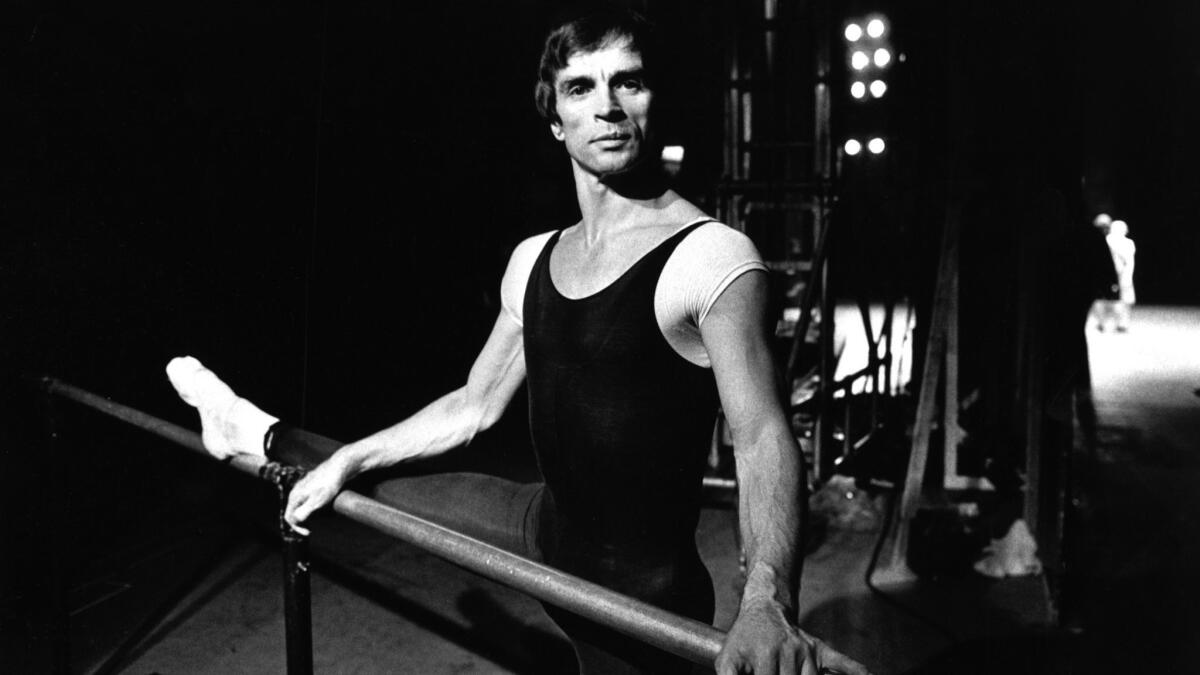

‘White Crow’ celebrates dancer Rudolf Nureyev’s life and legend

No one was quite prepared for what they saw when Rudolf Nureyev was unleashed.

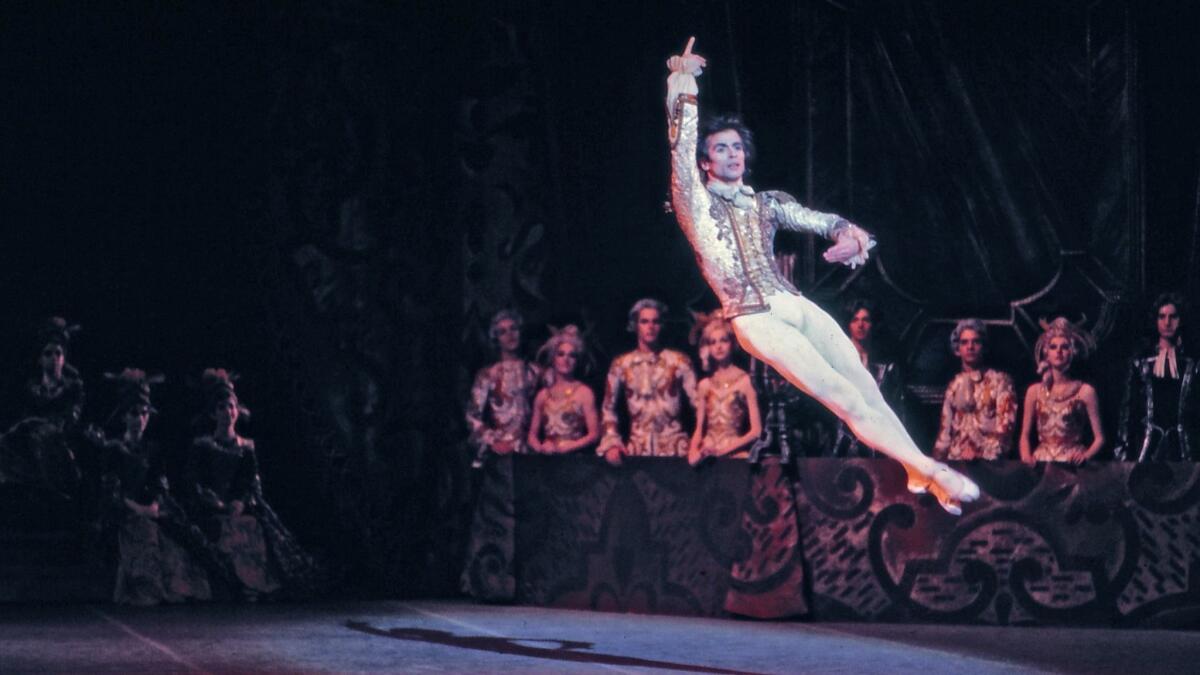

It wasn’t just the iconic dancer’s athletic abandon, though that was impressive enough. He turned faster than anyone and sprang higher, using just a slight plié (bend of the knees) to launch himself from the floor. His leap arced like a rainbow and he returned to earth easily, lightly.

His technique was never perfect, but that was part of the impetuous, wild quality that made him so alluring to audiences around the world.

His stage demeanor demanded attention: supremely confident and authoritative. He had a self-awareness that audiences could feel, and it dominated his most famous portrayals. This wasn’t “Swan Lake’s” run-of-the-mill Siegfried, it was Nureyev remaking Siegfried — and crowds went crazy.

Those who witnessed his genius will never forget it. But Nureyev is barely known to many 58 years after he defected from the Soviet Union at Paris’ Le Bourget Airport to begin a triumphant career in the West. A new movie from Sony Pictures Classic aims to correct that. Called “The White Crow” — the title comes from an expression describing someone different from the norm — it opens Friday in Los Angeles.

Directed by actor Ralph Fiennes (who also appears as the influential ballet master Alexander Pushkin) with a screenplay by David Hare, “The White Crow” ” jumps from Nureyev’s impoverished childhood in Ufa, a city near the former Soviet Union’s Asian border, to his training at St. Petersburg’s famed Vaganova Choreographic Institute, to the Kirov Ballet’s fateful 1961 tour to Paris.

At the Paris airport, the KGB was going to send him back to the Soviet Union even though the rest of the company was continuing on to London. In a fit of panic, the dancer bolted, fearing he’d never get out of the country again.

“It was not a ‘leap to freedom’ in the language of Western propaganda,” said Hare, who actually met Nureyev in the mid-1960s when the future playwright and screenwriter was a student at Cambridge. “He was going to pursue his talent. He was willing to make the absolute sacrifice at Le Bourget Airport, which is to leave his homeland and his family. He knows he can only develop his gift in the West.”

Nureyev was born to Tatar Muslim parents in March 1938 on a train journeying across Siberia. He became consumed with dancing as a young child, but there were few opportunities in Ufa. He knew he had to get to Leningrad (later St. Petersburg) to fulfill his outsized dreams.

At the late age of 17, he was admitted into the country’s most elite ballet academy. Even though his technique was raw, teachers recognized his exceptional talent. Studying with Pushkin — who later coached Mikhail Baryshnikov — Nureyev worked harder than anyone else, making up for lost time. An autodidact, he was known for his furious work ethic, never missing class or rehearsal and adhering to a punishing schedule of 250 performances annually throughout his 25-year career.

He was admitted into the Kirov Ballet (now the Mariinsky) in 1958, and at his debut performance partnered the company’s prima ballerina, Natalia Dudinskaya. Before his defection, rumors had already filtered to Western balletomanes about an exceptional young dancer there, so the company’s first tour to Paris had been highly charged.

One of his first stops as a free man was London, and he was paired with the Royal Ballet’s prima ballerina, Margot Fonteyn. She was renowned for her refinement and elegance; he was untamed fervor. She was twice his age, yet even that became an asset. Sir Frederick Ashton, dean of British ballet, made the romantic one-act “Marguerite and Armand” for them, based on the French novel about a courtesan and her lover. People who had never given ballet a second thought waited in long lines to see them.

On top of all that, he was beautiful, with penetrating eyes, full lips and flat cheekbones. He wore his hair long, like the Beatles did, bringing the era’s youth culture to a centuries-old art form.

The ballet boom was on.

Fiennes came to Nureyev’s story through Julie Kavanagh’s definitive biography, “Nureyev: The Life,” which he read almost 20 years ago. The man’s early years grabbed Fiennes, and he believed it would make a powerful movie.

“It’s only a few people who can transcend the technique of ballet to something that’s truly expressive,” he said in a phone interview from the set of the latest “Kingsman” movie, in which he has a role.

“I’ve sat through some traditional ballet productions where it was hard for me to engage until a dancer comes on that has something inside them,” Fiennes said. “It’s like Pushkin says in the film” to the young Nureyev: “What is your story? What are you exactly saying” with your dancing?

The director knew he wanted a dancer for the lead role, and following an exhaustive search of all the major Russian companies, scouts found Oleg Ivenko, a principal dancer with the Tartar State Ballet. Although he doesn’t duplicate Nureyev’s style — no one could, Fiennes and Hare acknowledge — Ivenko looks somewhat like the young “Rudik.”

Speaking through an interpreter, Ivenko said he didn’t know much about Nureyev before the film; his ballet teachers never discussed him. “I knew he was a famous dancer just like Baryshnikov, and I watched his movies, recordings of his dances,” Ivenko said. “But I didn’t know what kind of personality he had. I should have because that was the most interesting part.”

Indeed, Nureyev was a highly complex man, and not always for the good. He was tempestuous and often unkind. He was infamous for his temper, and he would turn on close friends. Hare said he believed Nureyev’s imperiousness came from the poverty of his youth and a sense of social grievance.

Dance and work were his salvation. He was one of the first ballet stars to branch out into modern dance (Martha Graham, Murray Louis). He restaged Russian masterworks on Western companies, such as “The Kingdom of the Shades” from “La Bayadere.” He acted in films (Ken Russell’s “Valentino”) and onstage (“The King and I”).

As artistic director of the Paris Opera Ballet, he staged a Hollywood version of “Cinderella” (seen in Orange County in 1988), added works by Paul Taylor, Merce Cunningham and Jerome Robbins to the repertory, and promoted a young and exciting slate of stars, among them Sylvie Guillem and Laurent Hilaire.

Still, a dancer’s glory years are short-lived. Nureyev’s lasted from the early 1960s through the early ’70s, but he kept going, much longer than he should have. His last performance was in 1992. He died in January 1993 from AIDS.

Those who saw Nureyev in his prime, especially, will tell you about his exalted presence. He has imprinted himself in their memories. And maybe that’s quite good enough, even for a legend.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.