Robert Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman’s on-screen alliance

The letter was two sentences long, addressed to “Dear Mr. Rossellini” and signed “Ingrid Bergman.” Like many moviegoers in the late 1940s, the actress was deeply affected by “Rome, Open City” and “Paisan,” Roberto Rossellini’s landmarks of neorealist cinema. Alone among the Italian director’s admirers, she offered her star power and talents, as “a Swedish actress who speaks English very well,” in hope of an on-screen collaboration.

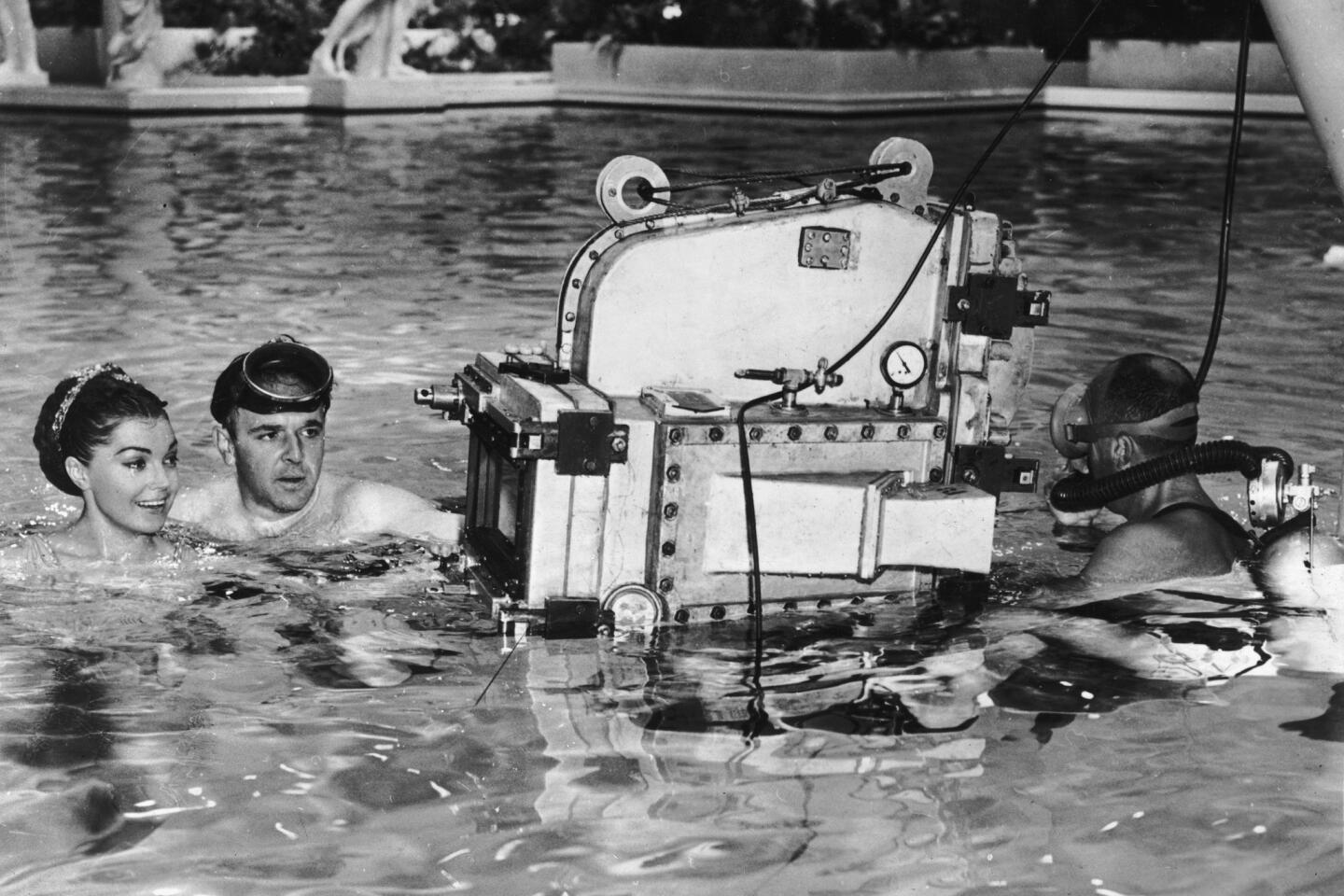

Rossellini accepted eagerly. But any expectation that Bergman’s high profile would heighten his clout at the box office were dashed. Together they would make five features and a short, none of which clicked with audiences or critics. The combination of Hollywood star and European auteur gave rise to unpredictable films that couldn’t be pigeonholed as neorealism or melodrama, though they contained elements of both.

Years later, after the scandal surrounding their adulterous love affair had subsided into yesterday’s news and with subjective directorial visions like Rossellini’s thriving on the art-house circuit, the work was reassessed with a newfound appreciation for its gutsiness and aesthetic power.

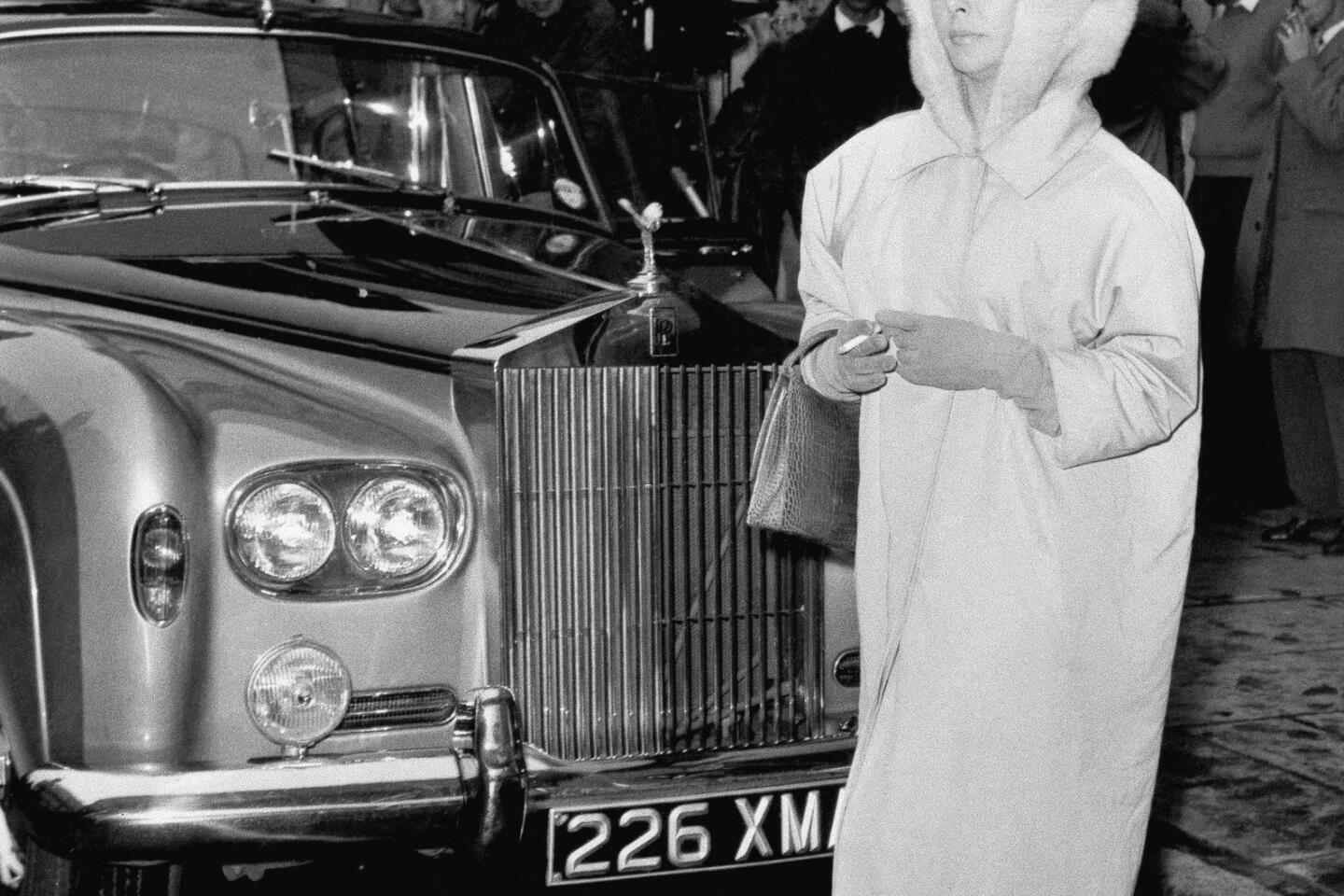

SNEAKS: Movie trailers, full coverage

The couple’s first three movies together — “Stromboli,” “Europe ‘51” and “Journey to Italy,” all of which revolve around a foreign woman in Italy and a difficult marriage — are daringly modern films, undimmed by time. They’ve been restored and compiled, with a rich array of extras, in a set from Criterion Collection released last week.

Turning his attention from the open wound of the war to the ways that life on the continent was resuming in its aftermath, Rossellini leapt into a new type of storytelling, one driven more by atmosphere and state of mind than by incident. Well before Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman would bring alienation to the forefront of international cinema, he used striking landscapes and cityscapes — an active volcano, dilapidated housing projects, the ruins of Pompeii — to explore troubled relationships.

Dissociating himself from the neorealist school wasn’t simple for a director regarded as one of its leading proponents. But for Rossellini, the label referred to a “moral stance,” one that didn’t depend on depictions of working-class life. Though he favored nonprofessional actors and location shooting, he now had Bergman’s glamour and fame as instruments in his creative arsenal, and he used them wisely. There’s a metafictional commentary at play in their collaborations: She’s the outsider playing the outsider, the northerner who’s not quite at ease in the south.

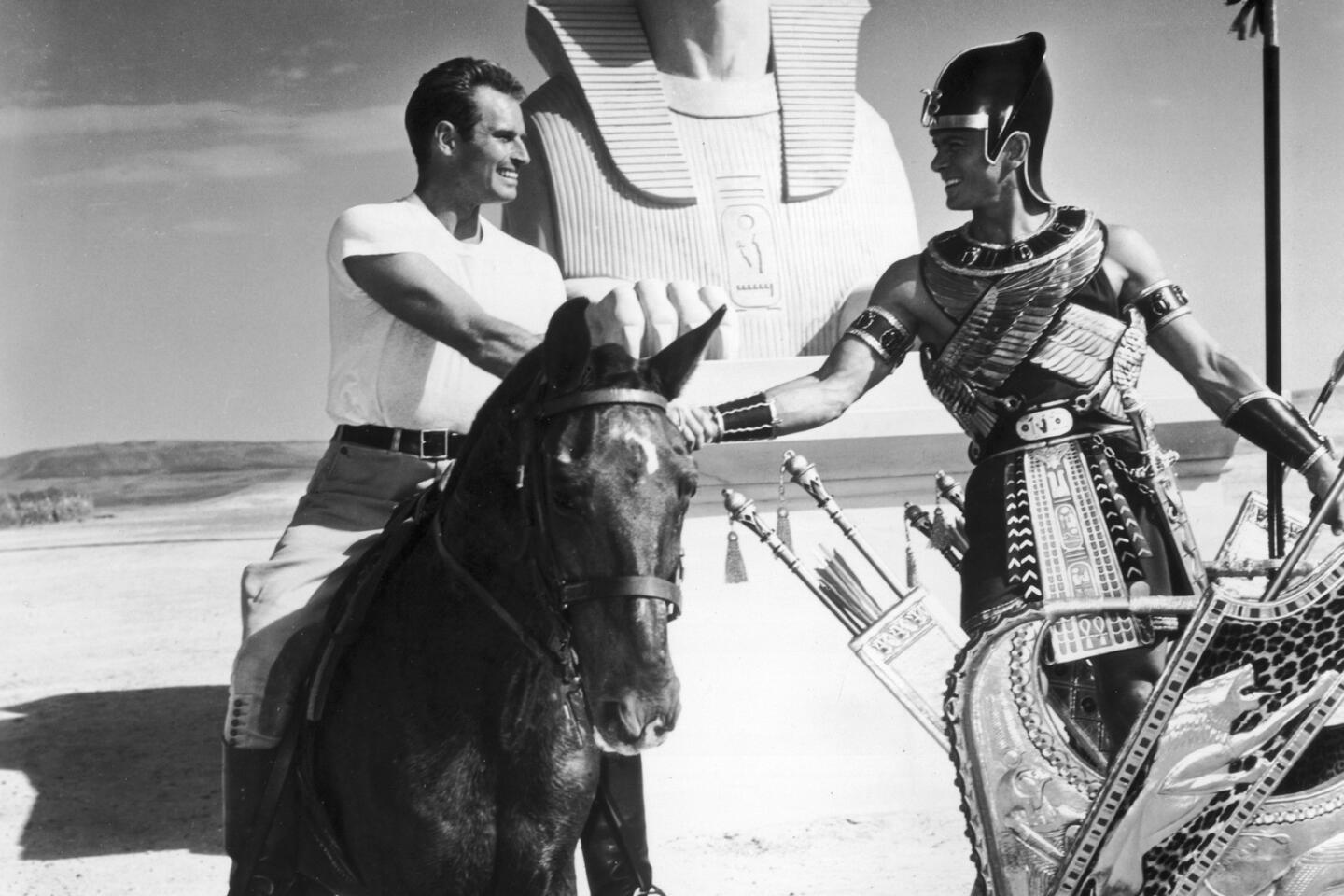

PHOTOS: Billion-dollar movie club

For “Stromboli” (1950), the project on which the director and star fell in love, Rossellini wrote Bergman’s pregnancy into the film, an act of affirmation. By the time they were making 1954’s “Journey to Italy,” with its scorching portrayal of an exhausted marriage, their own off-screen partnership was in trouble. (They divorced in 1957 but remained devoted friends.)

“Stromboli” is set on the Aeolian isle of the title, a sun-parched piece of rock off the coast of Sicily that hadn’t a hotel when the entertainment press headed there for scoops on the couple. Bergman plays Karin, a Latvian war refugee whose attempt at a new life leaves her in utter despair. After her other options fall through at a camp for displaced persons near Rome, she marries the soldier with whom she’s been flirting across the barbed wire. On his native Stromboli, towering over the elderly black-garbed women, she feels like a member of “a different race.”

Variously angry, imperious, despondent and outraged that “a woman like me” should be trapped in such a place, she’s not a sympathetic character. And yet through Bergman’s fearless performance and Rossellini’s astute visuals, Karin’s epiphany — on the slopes of the island’s far-from-dormant volcano, no less — is a stirring narrative feat with an unexpected spiritual component.

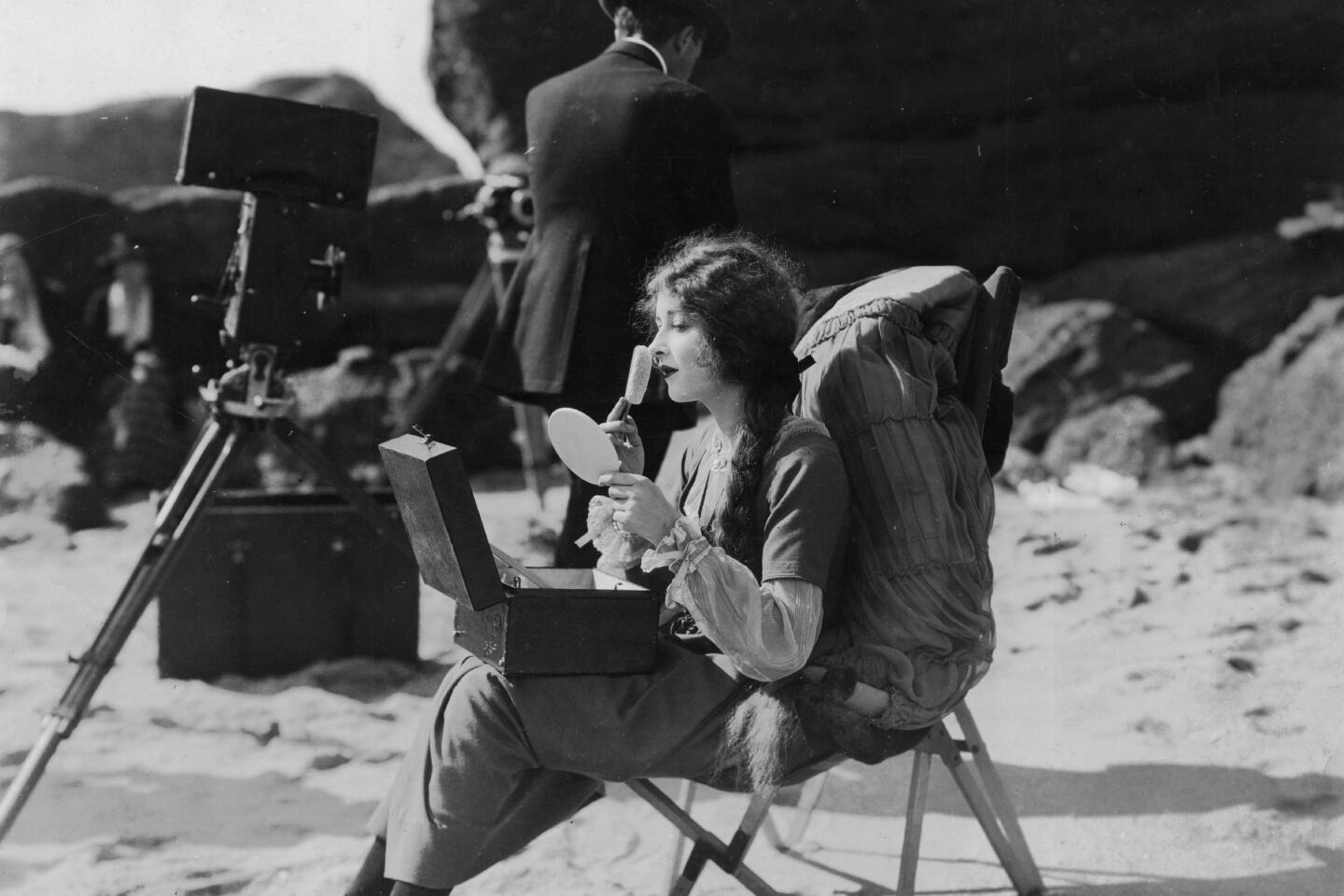

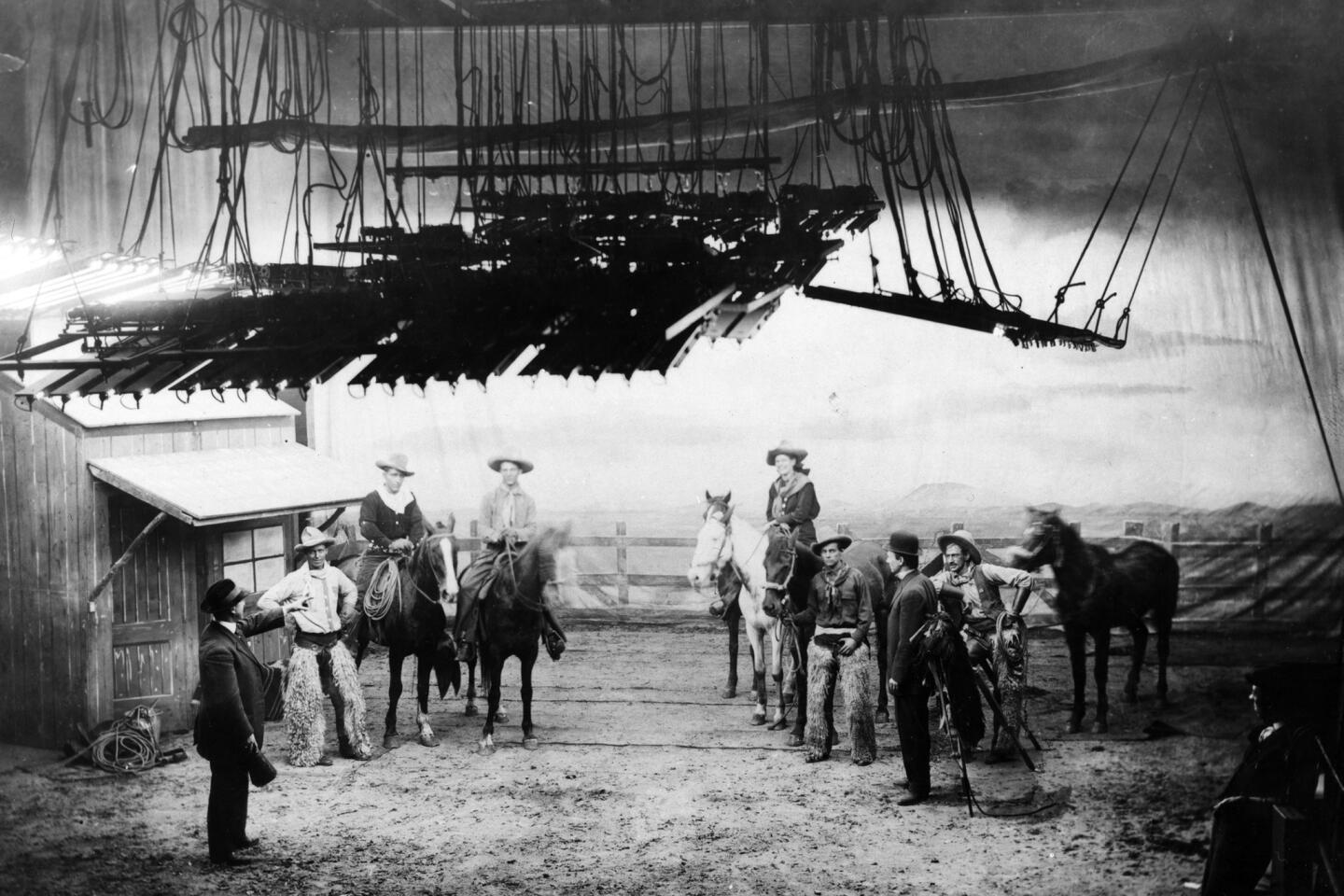

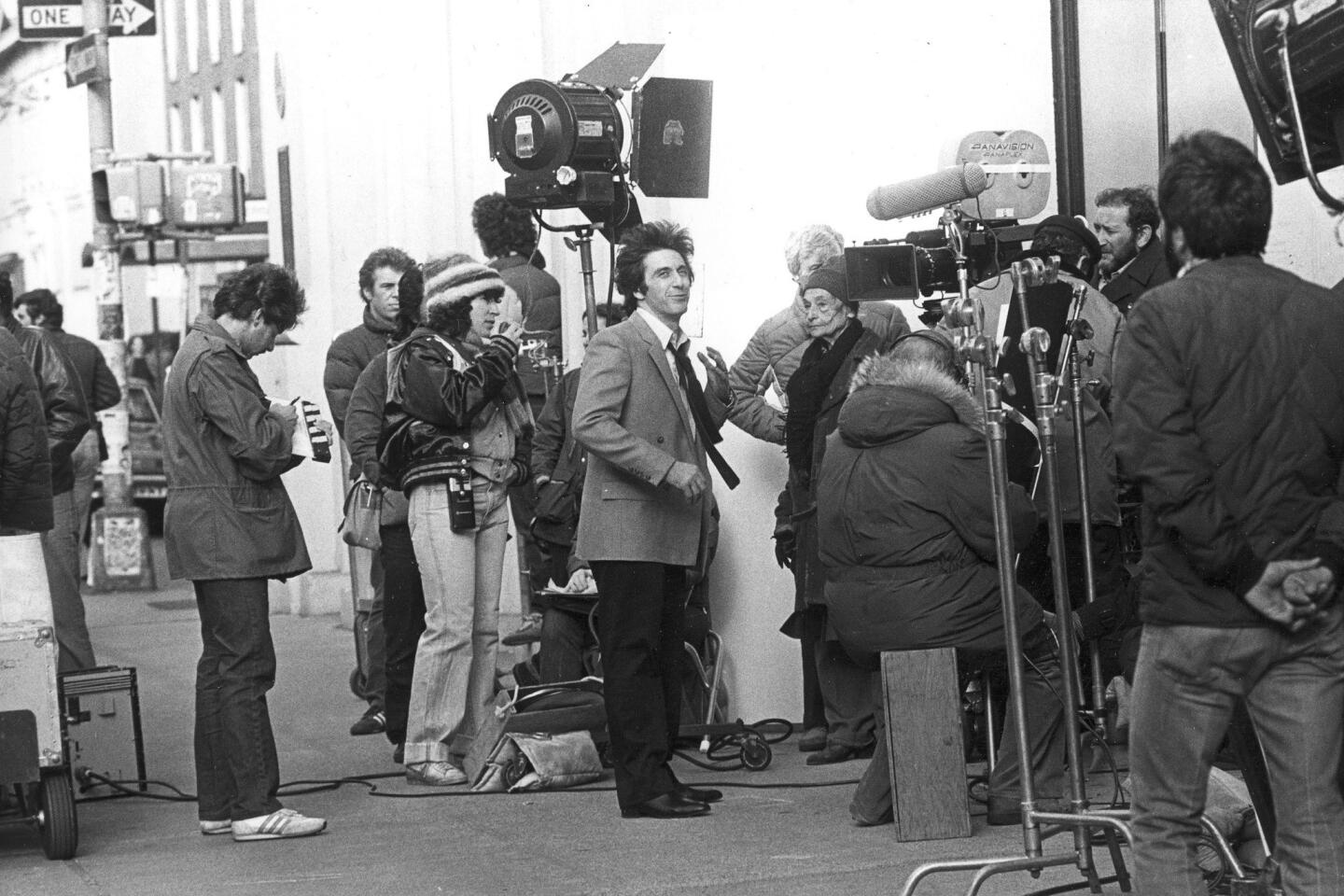

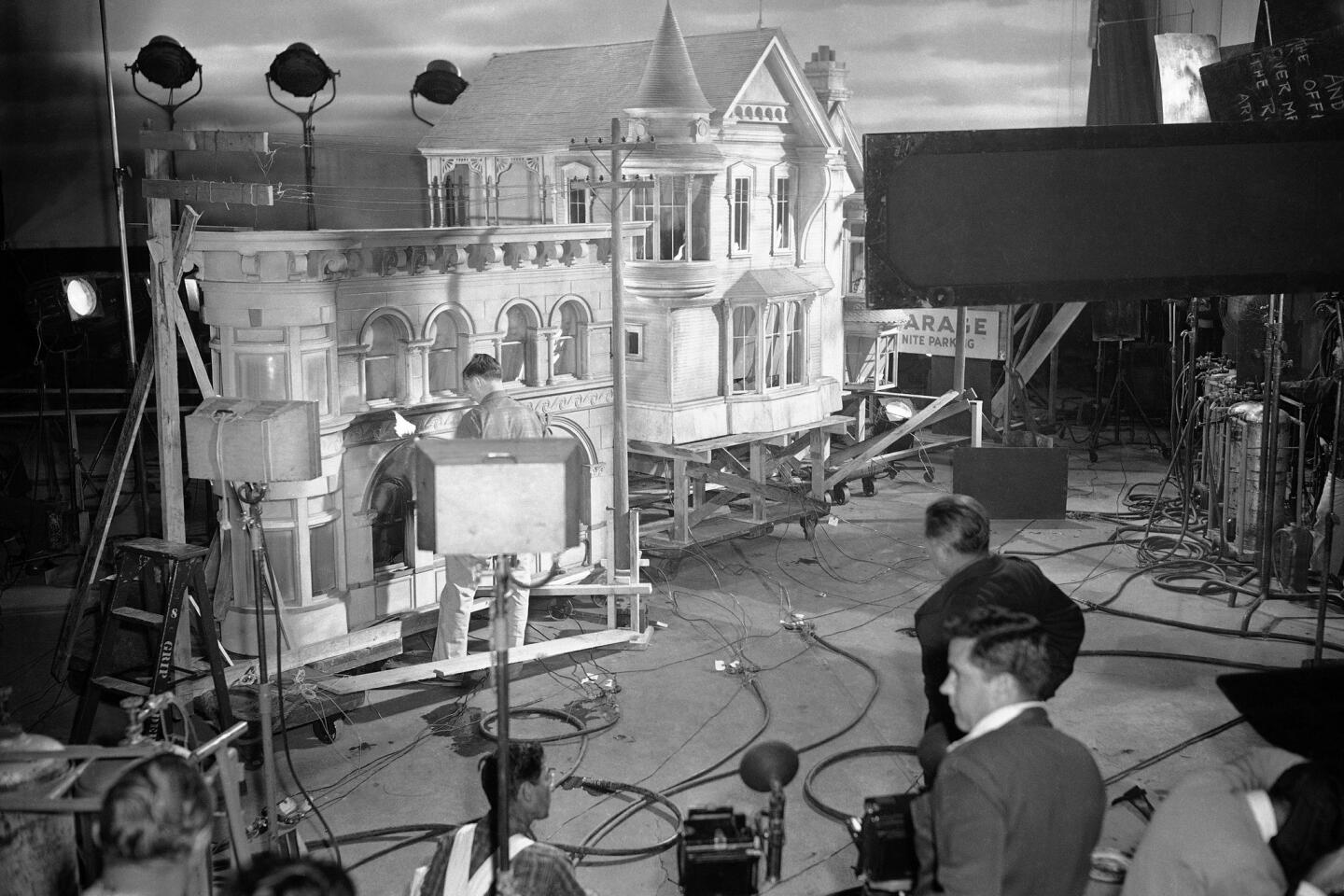

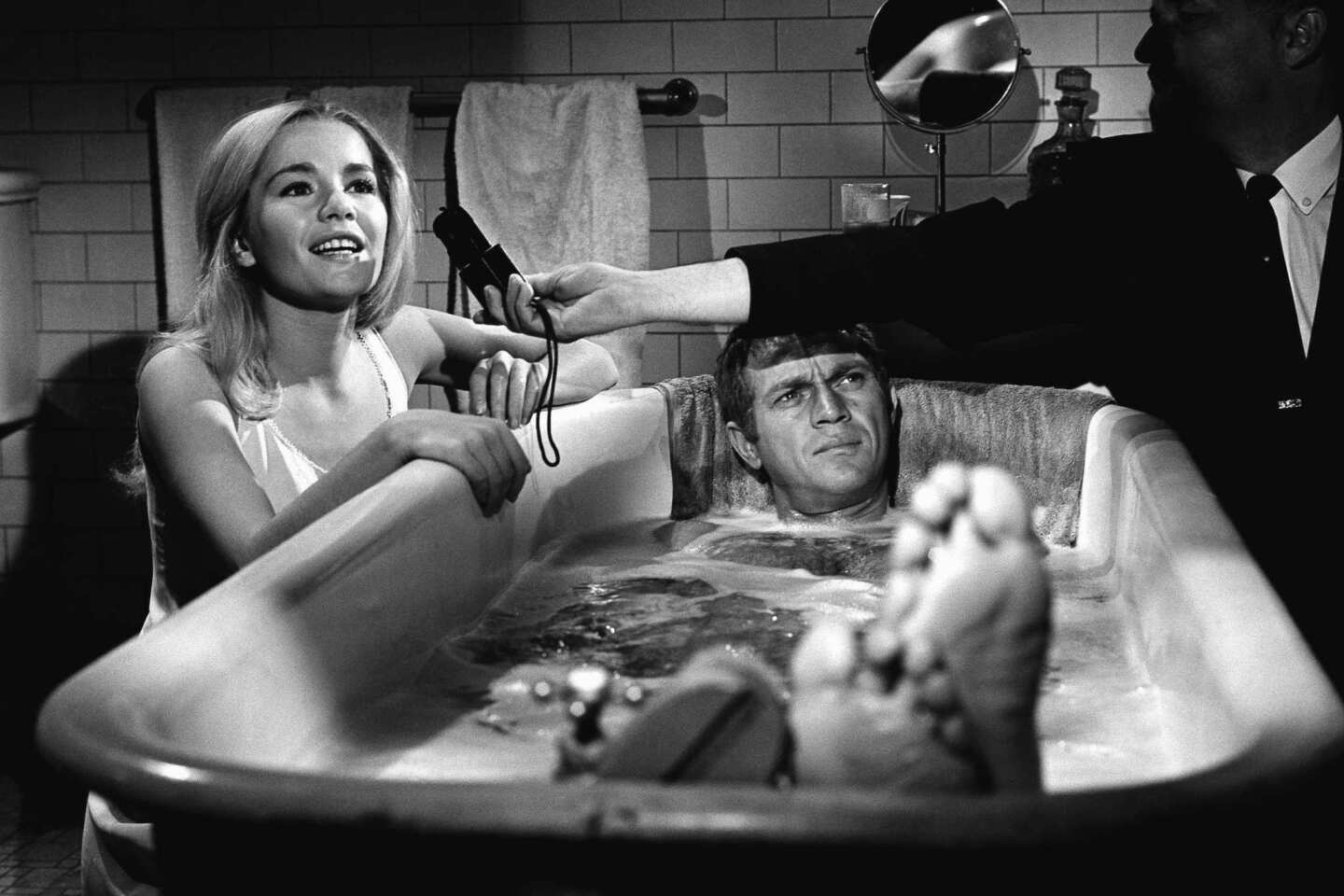

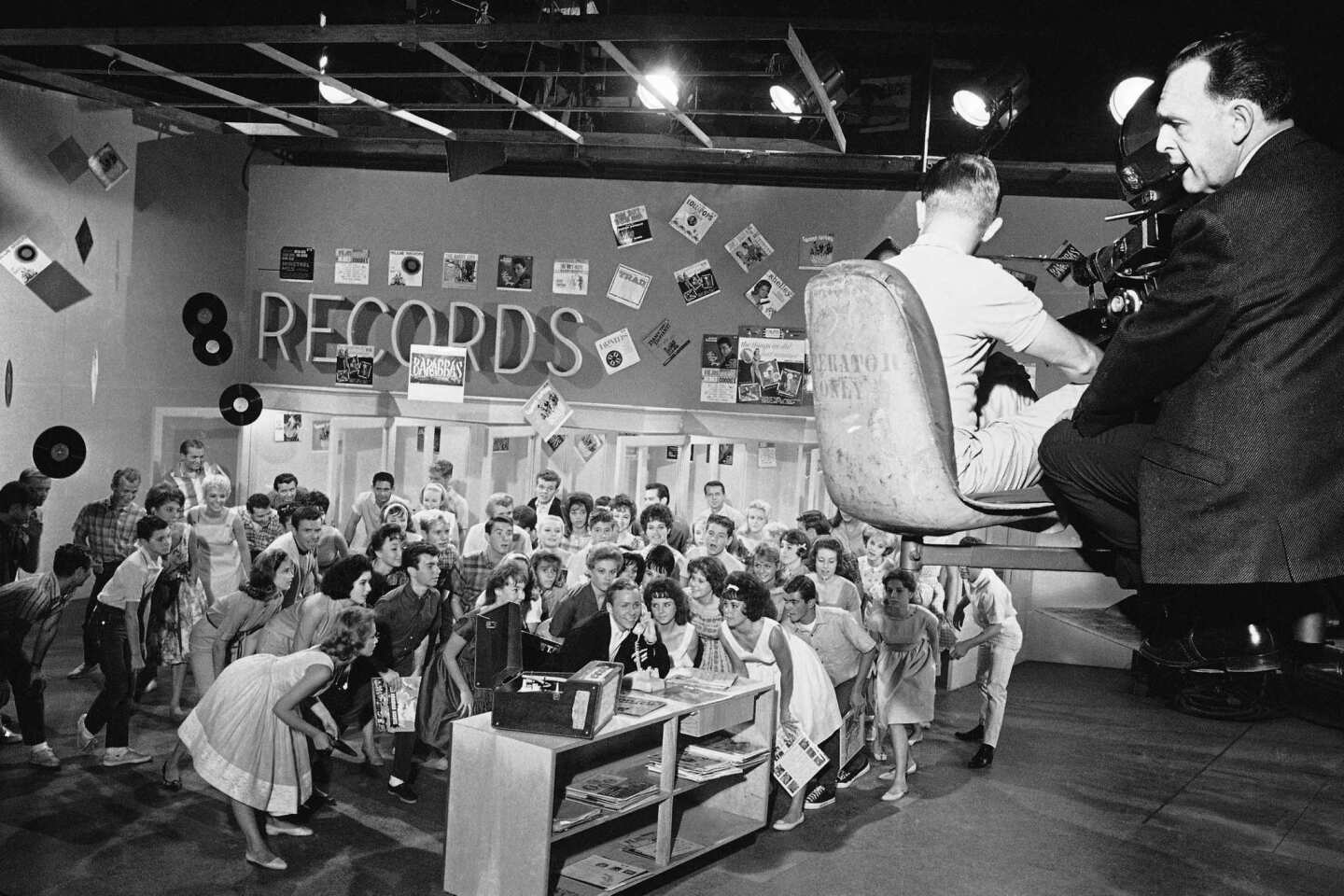

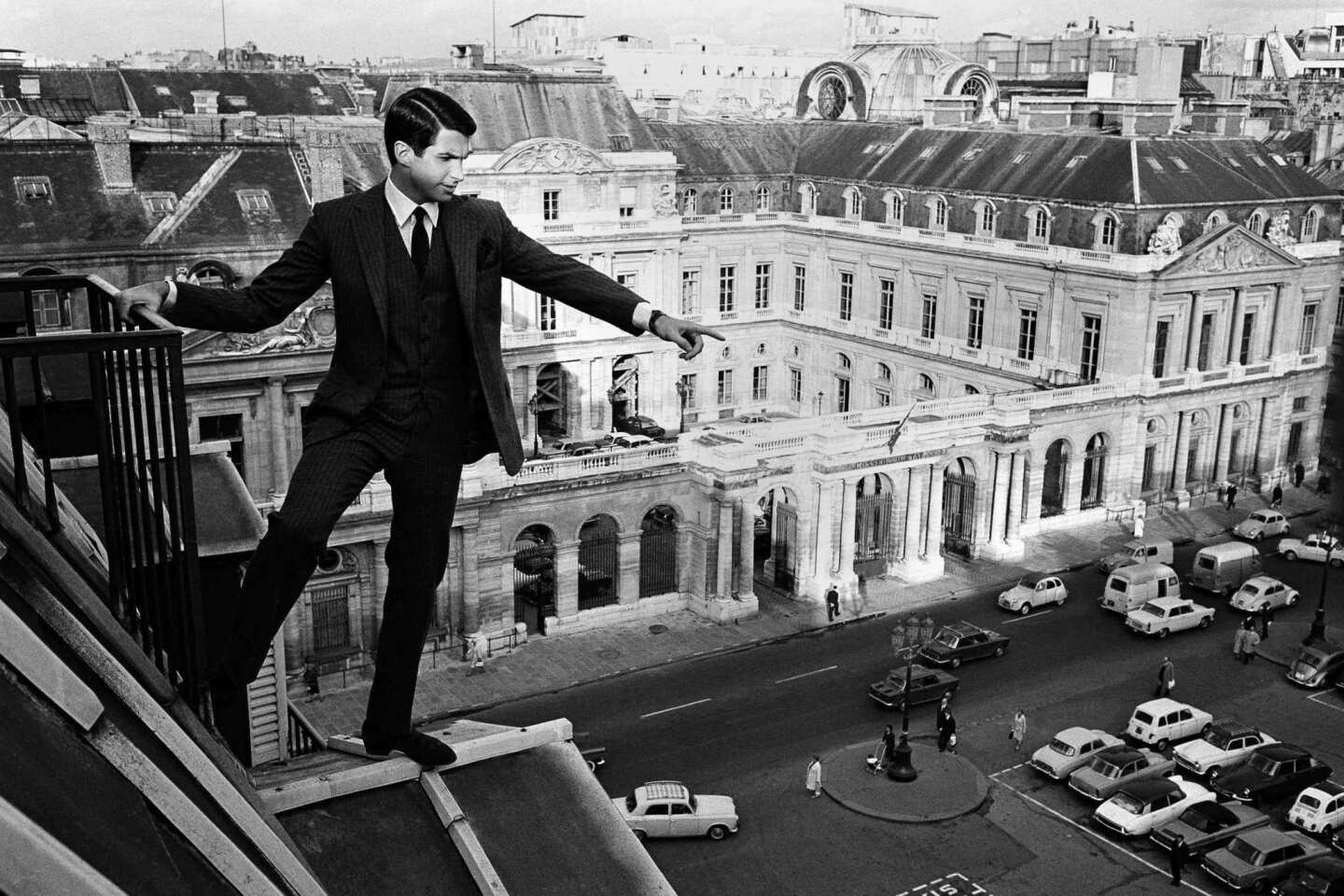

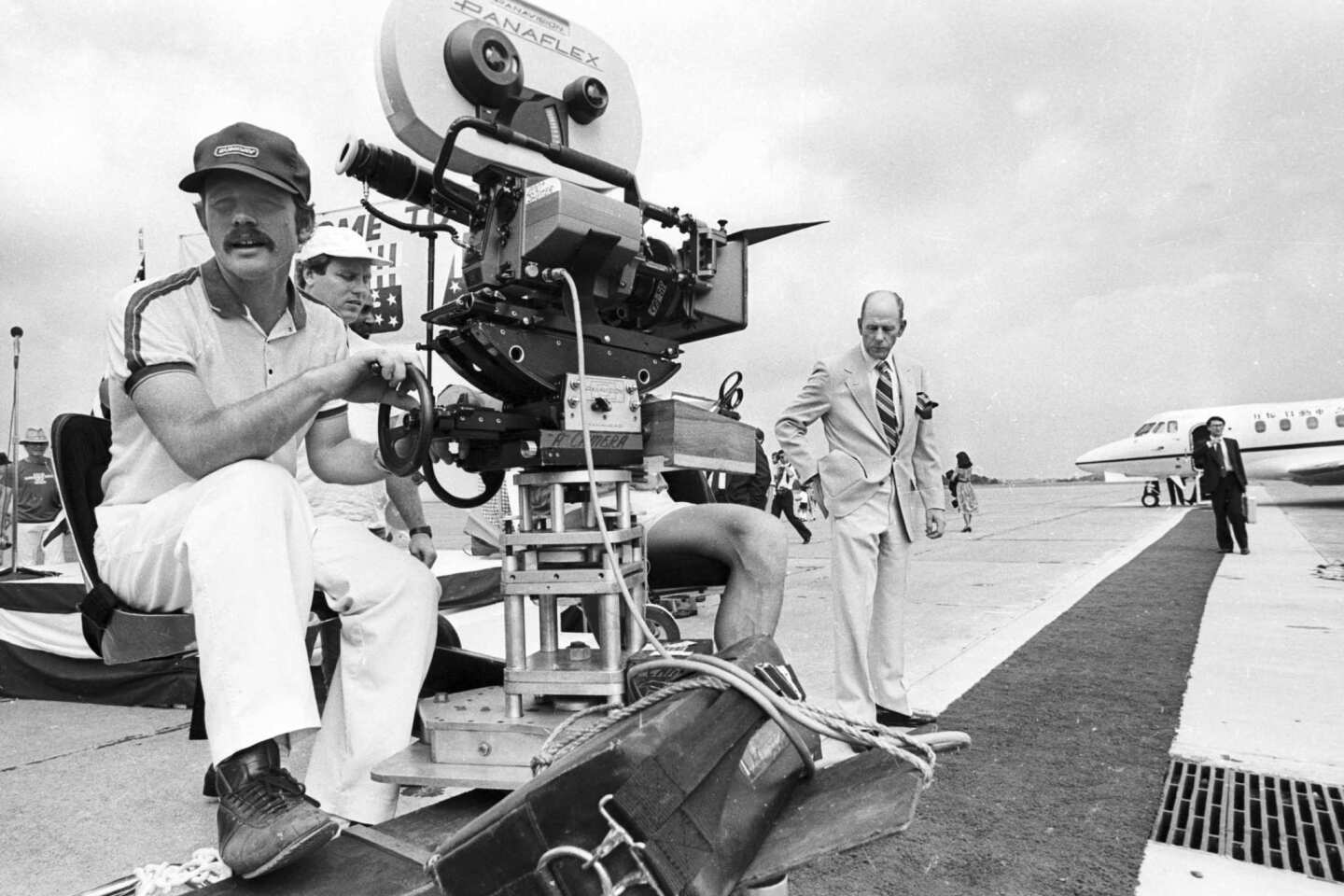

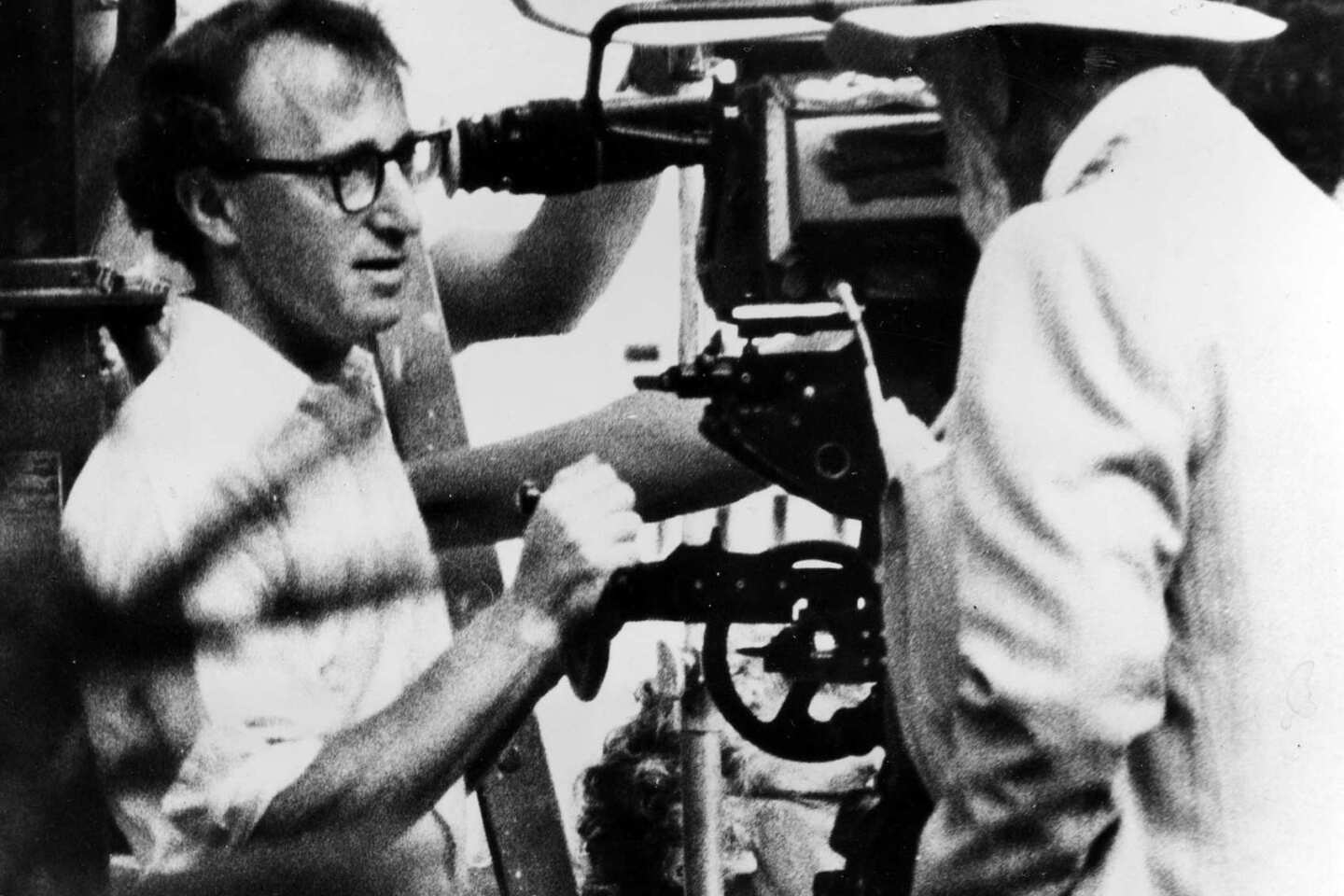

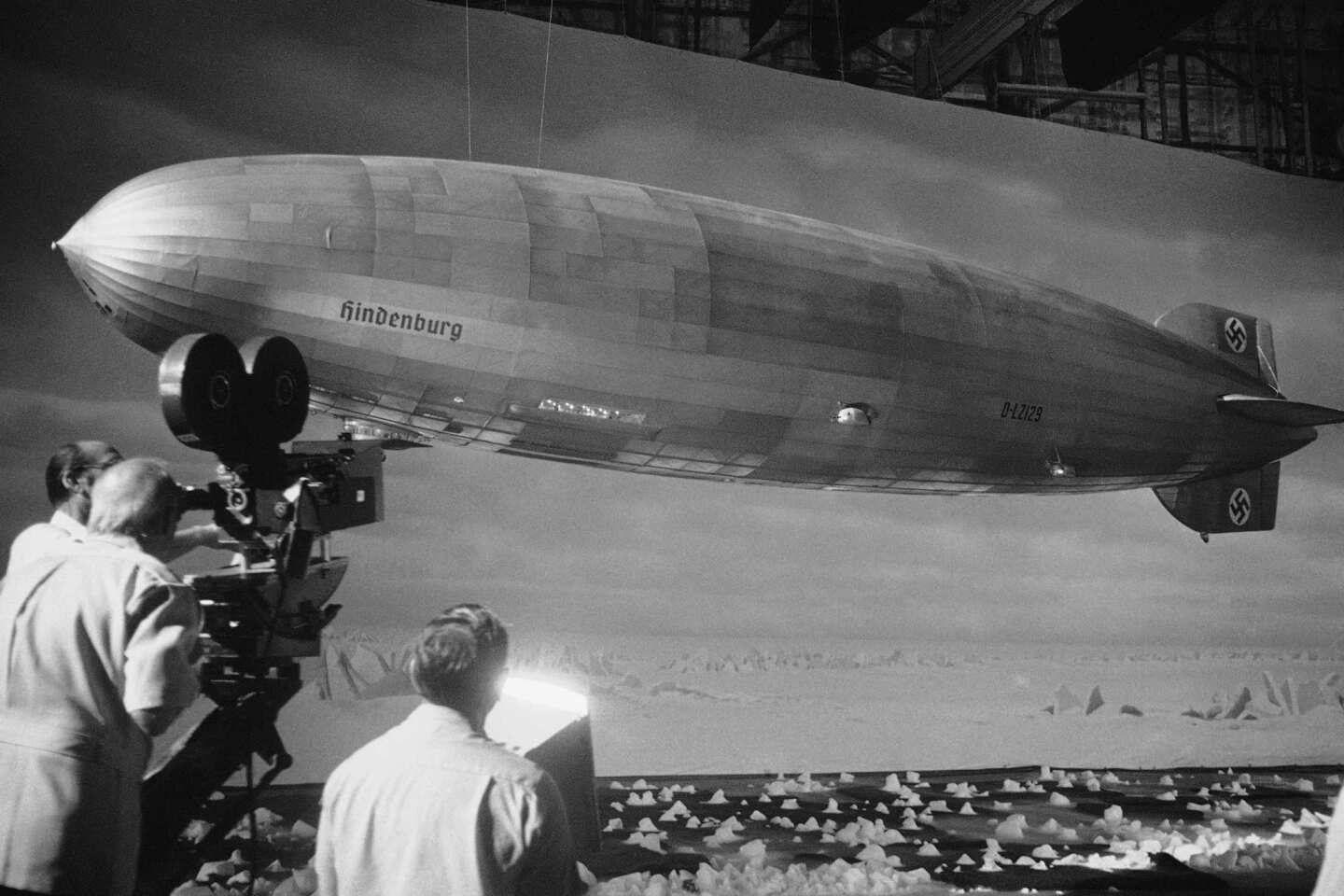

PHOTOS: Hollywood backlot moments

Spirituality is more overt in the couple’s next feature, “Europe ‘51,” and another volcano, Vesuvius, looms large in “Journey to Italy,” whose soul-baring use of tourism has become a template for films as recent as the September release “And While We Were Here.”

At once melodramatic and austere, “Europe ‘51” casts Bergman in a harsh light and then a beatific one as Irene, a character inspired by St. Francis of Assisi (the subject of an earlier film by Rossellini). A devastating loss inspires Irene to trade meaningless dinner-party chitchat for selfless pursuits.

Hers is a story of radicalization; her brief stint in a factory, where she’s dwarfed by machinery, is especially momentous. And yet “Europe ‘51” can be viewed as an argument against Cold War ideological divisions; Rossellini was courted and attacked by communists and Catholics alike. Openhearted and refusing to cast blame or take sides, Irene threatens the social order and therefore is deemed mad. As a priest tells her, “We must do good, but within limits.”

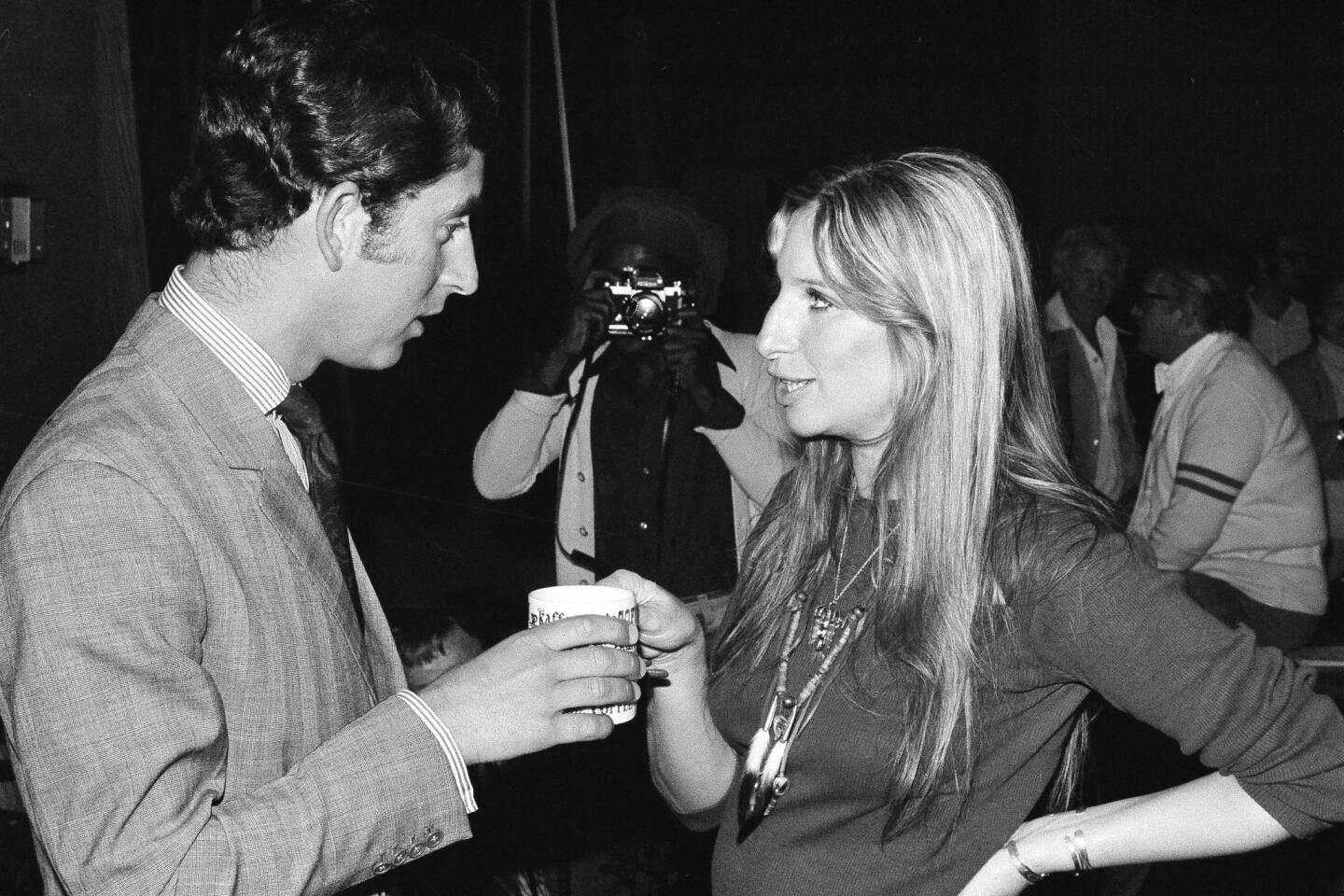

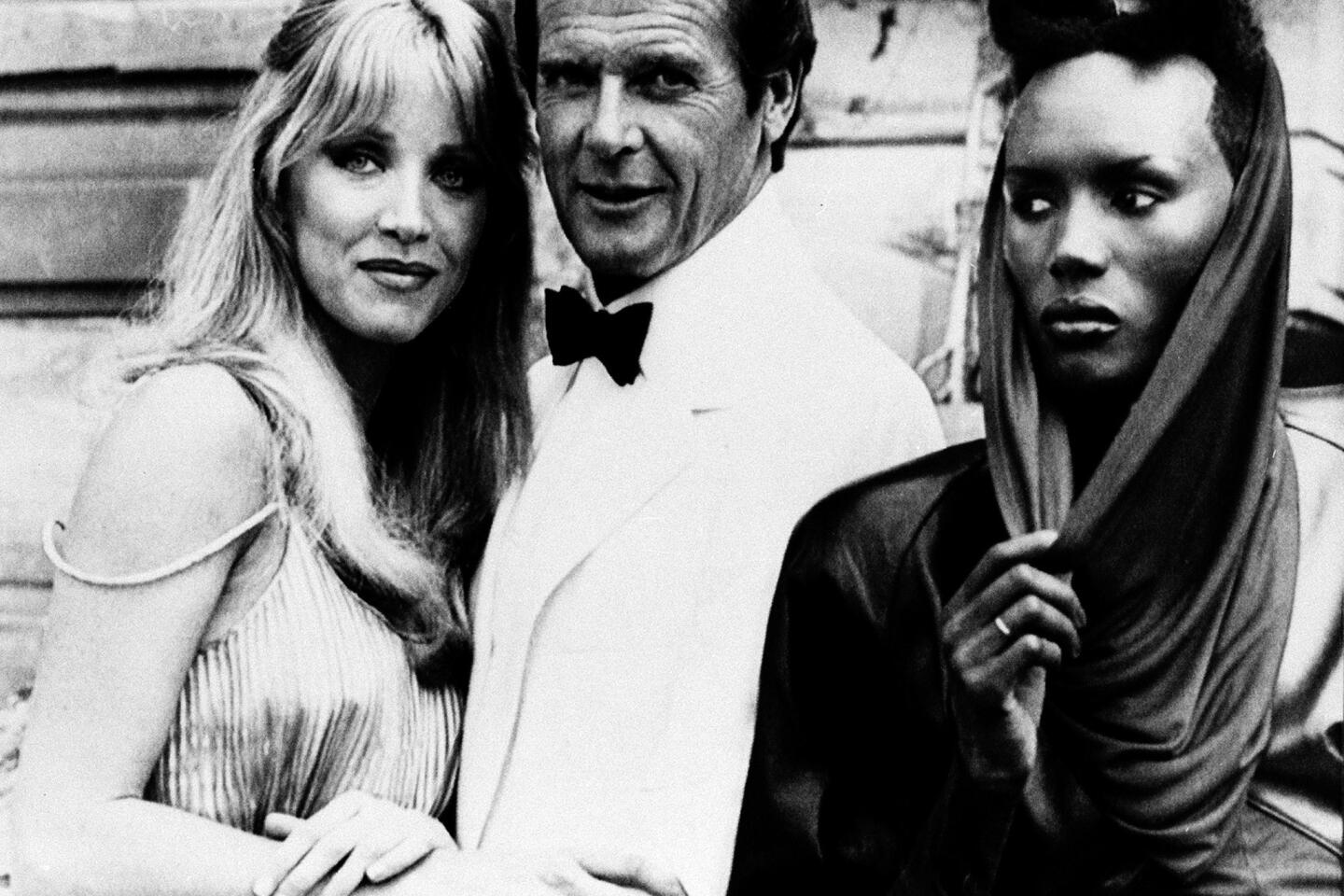

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

Openheartedness might as well be a quality from another planet for the married tourists in “Journey to Italy.” As a couple traveling from England to Naples in their Bentley, Bergman and George Sanders specifically locate the excoriating within the conversational. Beneath each lacerating complaint, though, lies a question, from one wary soul to the other.

Having made the trip to sell an inherited villa whose beauty they don’t appreciate, much as Karin doesn’t see the beauty of Stromboli, man and wife go their separate ways. He parties with a crowd of expats on Capri while she tours museums, lava fields, catacombs and sulfur pits. They wind up together at an excavation site at Pompeii that couldn’t be more resonant.

Sanders found Rossellini’s moment-to-moment methods exasperating. Whether Bergman, the unlikely muse who initially was drawn to his freedom, still felt free working with him is unclear. But there’s no doubt that the director knew how to use his stars’ beauty and misgivings to convey the moment-to-moment project of life. “My finales,” Rossellini said, “are turning points.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.