It occurs to you about 20 minutes into “The Big Short.” Actually, it probably occurred to most people 10 minutes in. But the Jets were losing and I’m a daydreamer. It’s a simple question, really: Should I root for these guys?

The characters in Adam McKay’s new film are, as those who read Michael Lewis’ source book know well, the adventuresome contrarians who foresaw the 2008 financial crash.

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

Over several years leading up to the crash, people such as Michael Burry (Christian Bale), Mark Baum (Steve Carell), Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt) and Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling), most of whom did not know one another, defy both conventional wisdom and their bosses with their unorthodox investments. With verve and style, McKay (“Talladega Nights” and its ilk) shows these characters making huge bets against the rising housing market, essentially gambling that the long-stable realm will all come crashing down and make their investments very lucrative.

The movie, which closed AFI Fest on Thursday, offers plenty of fodder for conversation. When it opens in December, it will certainly occasion a conversation about how we understand the 2008 economic crisis -- and whether, as a surprisingly ominous ending suggests, we could be heading right back to the precipice.

But cinematically speaking, the’re another interesting aspect involving just what kind of characters Baum and friends are. With the shorting-a-crisis premise, the movie is building to what we know will become one of the worst economic disasters in this country’s history. But that also of course leads to a big paradox; to arrive at the happy ending for the main characters is also to arrive at a cataclysm for everyone else.

1/78

Actor Christian Bale takes pictures and signs autographs with fans lining Hollywood Boulevard before walking the red carpet for the premiere of “The Big Short” on the closing night of AFI.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 2/78

Actors Lily Rabe, left, and Hamish Linklater giggle on the red carpet for the premiere of “The Big Short.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 3/78

Ryan Gosling, Christian Bale and other cast members leave the theater after director Adam McKay introduced the premiere of “The Big Short” on closing night of the AFI festival.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 4/78

Actor Steve Carell joins Melissa Leo on the red carpet for the premiere of “The Big Short” on closing night of the AFI Fest.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 5/78

Actress Karen Gillan does her thing on the red carpet for the premiere of “The Big Short” on the closing night of the festival.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 6/78

Actor Ryan Gosling is captured on the red carpet for the premiere of “The Big Short” on the closing night of the festival.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 7/78

From left, actors Ryan Gosling, Marisa Tomei and Steve Carell get chatty on the red carpet for the premiere of “The Big Short” on the closing night of the AFI festival.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 8/78

Actor Finn Wittrock is captured on the red carpet for the premiere of “The Big Short” on the closing night of the festival.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 9/78

Will Smith poses with fans near the TCL Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, where he’d arrived Tuesday for the AFI Fest premiere of his film “Concussion.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 10/78

Will Smith, with producer Giannina Facio and her partner, writer/producer/director Ridley Scott, have a laugh before the premiere of “Concussion” at AFI FEST 2015.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 11/78

Actor Will Smith poses for photos and signs autographs for fans lined up along Hollywood Boulevard on Tuesday.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 12/78

Dr. Julian Bailes, former team physician for the Pittsburgh Steelers, greets former NFL lineman Leonard Marshall, right, before the premiere of “Concussion.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 13/78

Actor Will Smith, right, with director Peter Landesman on the red carpet.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 14/78

Musician Leon Bridges, left, and actor Will Smith before the premiere of “Concussion.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 15/78

Actress Sara Lindsey on the red carpet for the premiere of “Concussion” at AFI Fest on Tuesday.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 16/78

Actress Gugu Mbatha-Raw in Hollywood for the premiere of “Concussion.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 17/78

Actors Mike O’Malley, left, and Will Smith on the red carpet for their film “Concussion.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 18/78

Actors Mike O’Malley, from left, David Morse, Sara Lindsey, Will Smith, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje and Albert Brooks pose before the premiere of their film “Concussion.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 19/78

Sports broadcaster Bob Costas, second from left, greets actor Will Smith, right, on the red carpet.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 20/78

Actresses Gugu Mbatha-Raw, left and Sara Lindsey attend the Sony after-party following the premiere of “Concussion” at AFI Fest 2015.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 21/78

Actor Will Smith and Dr. Bennet Omalu, whom Smith portrays in “Concussion,” attend the Sony after-party at the Hollywood Roosevelt hotel.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 22/78

Producer and director Ridley Scott borrows a camera to take a group photo at the “Concussion” after-party.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 23/78

Actor Ewan McGregor speaks to reporters before the film “Last Days in the Desert” at AFI Fest 2015 on Wednesday.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 24/78

Actor Ewan McGregor, left, and director Rodrigo Garcia pose for photos before showing their film “Last Days in the Desert” on Wednesday at AFI Fest.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 25/78

The cast and four of the Chilean miners whose stories are told in the “The 33” pose on the red carpet before the film’s premiere at AFI Fest.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 26/78

Mario Gomez, from left, Luis Urzua, Edison”’Elvis” Peña and Juan Carlos Aguilar at the Hollywood premiere of “The 33,” the film that tells their story of being trapped in a Chilean mine.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 27/78

Actress Juliette Binoche before the premiere of “The 33” at the TCL Chinese Theatre in Hollywood.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 28/78

Actor Jacob Vargas, right, poses with Edison “Elvis” Peña, the Chilean miner he portrayed in “The 33.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 29/78

A model of the rescue capsule used to save the Chilean miners is displayed at the premiere of “The 33.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 30/78

Actor Antonio Banderas, who stars in “The 33,” and Nicole Kimpel on the red carpet at AFI Fest in Hollywood.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 31/78

Juliette Binoche and Antonio Banderas before the premiere of “The 33.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 32/78

“The 33” actresses Kate Del Castillo, from left, Cote de Pablo and Juliette Binoche on the red carpet.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 33/78

Author and former Los Angeles Times reporter Hector Tobar on the red carpet for “The 33.” The film was adapted from Tobar’s book “Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine, and the Miracle That Set Them Free.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 34/78

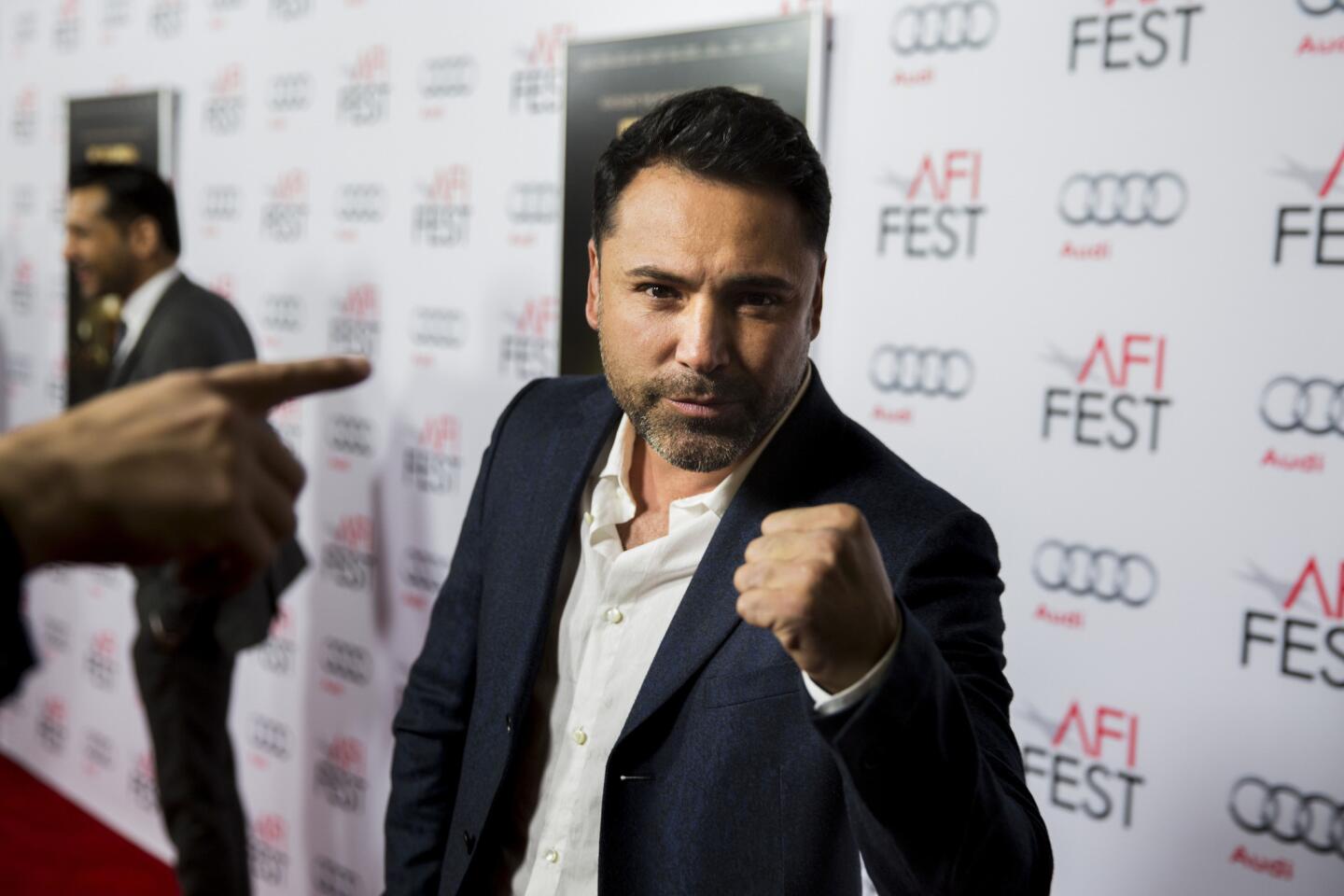

Oscar De La Hoya poses for photos before the premiere of “The 33” at AFI Fest.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 35/78

Sylvester Stallone and his wife, Jennifer Flavin, at “The 33” oremiere.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 36/78

Sylvester Stallone, right, gets a hug from Chilean miner Luis Urzua as actor Lou Diamond Phillips watches.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 37/78

Actress Cote de Pablo, center, poses with Chilean miners Luis Urzua, from left, Juan Carlos Aguilar, Mario Gomez and Edison “Elvis” Peña and producer Mike Medavoy before the premiere of “The 33.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 38/78

The cast of the film “Mustang” and director Deniz Gamze Ergüven, far right, arrive to be photographed at AFI Fest.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 39/78

Sony Pictures Classics’s copresidents and cofounders, Michael Barker, left and Tom Bernard, pose with Hungarian director László Nemes, center, before the showing of his film “Son of Saul” on Monday.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 40/78

Hungarian director László Nemes, left, and his lead actor Geza Ršhrig before the showing of their film, “Son of Saul,” at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 41/78

Director Michael Moore arrives Nov. 7 for the showing of his new film, “Where to Invade Next,” at AFI Fest 2015 at Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 42/78

Director Michael Moore walks the red carpet before showing his new film, “Where to Invade Next,” on Nov. 7 at Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 43/78

Actress Sally Kirkland poses on the red carpet before the showing of director Michael Moore’s “Where to Invade Next” on Nov. 7.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 44/78

Actor Richard Chamberlain poses for photographers on the red carpet before a showing of Michael Moore’s “Where to Invade Next” on Nov. 7.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 45/78

Actor Sam Waterston walks the red carpet before the showing of director Michael Moore’s “Where to Invade Next” on Nov. 7 in Hollywood.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 46/78

Director Michael Moore introduces “Where to Invade Next” at AFI Fest 2015.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 47/78

Producer Carl Dean, left, director Michael Moore and producer Tia Lessin introduce their new film, “Where to Invade Next,” at AFI Fest 2015 in Hollywood on Nov. 7.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 48/78

Movie fans line up along North McCadden Place in Hollywood for a showing of Michael Moore’s “Where to Invade Next” at AFI Fest 2015.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 49/78

Gr’mur Hakonarson, director of the Icelandic film “Rams,” is photographed before heading into the theatre to introduce his film at the TCL Chinese 6 Theatres on the second night of AFI Fest 2015. There are 127 films from 45 countries showing in this year’s festival.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 50/78

Grimur Hakonarson, director of the Icelandic film “Rams,” does a brief interview with AFI Fest staff before introducing his film at the TCL Chinese 6 Theatres on the second night of the AFI Fest 2015 in Hollywood.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 51/78

Rafaella Biscayn, left, Sarah Bigle and Andrew Godoski have fun in a photobooth at an AFI alumni party at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel on the second night of the AFI Fest 2015.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 52/78

Director Nicholas Hytner, left, and actor Alex Jennings arrive to introduce “The Lady in the Van.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 53/78

Movie fans wait -- some seemingly a little longer than others -- for director Nicholas Hytner and actor Alex Jennings to arrive and introduce their film, “The Lady in the Van.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 54/78

Director Nicholas Hytner, left, and actor Alex Jennings introduce “The Lady in the Van.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 55/78

The room was full for an AFI alumni party at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel on the second night of AFI Fest 2015 in Hollywood.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 56/78

Attendees of the AFI alumni reception at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel mix and mingle.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 57/78

A couple of attendees of the filmmaker AFI alumni reception share a moment away from the crowd.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 58/78

A person checks her phone outside the penthouse suite of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel during a filmmaker welcome party that also previewed virtual-reality technologies.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 59/78

The scene outside the penthouse suite of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel during a filmmaker welcome party.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 60/78

Volunteer Cecilia Martin watches virtual-reality content, including content created by Google, during a filmmaker welcome party in the penthouse suite of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 61/78

People watch virtual-reality content during a filmmaker welcome party.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 62/78

People watch virtual-reality content produced by Vrse.Works.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 63/78

HOLLYWOOD, CA--NOVEMBER 05, 2015--Actress, writer, producer and director Angelina Jolie Pitt and her husband, actor Brad Pitt, pose on the red carpet for the opening night premiere of their new film, “By The Sea,” at AFI FEST 2015, presented by Audi, at TCL Chinese 6 Theatres, in Hollywood, CA, November 05, 2015. (Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 64/78

Actors Melvil Poupaud and Melanie Laurent, left, pose alongside actress-writer-producer and director Angelina Jolie Pitt and her husband, actor Brad Pitt, on the red carpet for the premiere of “By the Sea” in Hollywood.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 65/78

Angelina Jolie Pitt and Brad Pitt walk the red carpet.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 66/78

Angelina Jolie Pitt answers questions.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 67/78

Festival director Jacqueline Lyanga poses on the red carpet before the premiere of “By the Sea.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 68/78

Angelina Jolie Pitt and Brad Pitt draw a crowd, as usual.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 69/78

Actress Melanie Laurent of “By the Sea.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 70/78

Melanie Laurent, left, and Angelina Jolie Pitt talk backstage at the premiere of “By the Sea.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 71/78

An iPhone shows director Angelina Jolie Pitt speaking on the red carpet.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 72/78

Brad Pitt greets Donna Langley, chairman of Universal Pictures, on the red carpet for the premiere of “By the Sea.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 73/78

Brad Pitt greets fans at the AFI Fest.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 74/78

Fans hope to get autographs from Angelina Jolie Pitt and Brad Pitt.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 75/78

Angelina Jolie Pitt greets fans.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 76/78

Jacqueline Lyanga, AFI Fest director, introduces Angelina Jolie Pitt, right.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 77/78

Angelina Jolie Pitt waits alongside Brad Pitt, before introducing her film, “By the Sea,” at AFI Fest.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 78/78

Angelina Jolie Pitt walks up to introduce “By the Sea.”

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) “The Big Short” is set up with the movie screen-size challenges of a sports film and the gleeful abandon of a buddy comedy. Yet to root for its protagonists is to root for a disaster -- even more, it’s to root for people who exploit a disaster.

There have been plenty of comparisons to other films about Masters of the Universe, but it’s this last point that makes me think “The Big Short” is offering a different proposition from that of most movies about making money. Whatever the moral shadings of a “Wall Street” or a “Wolf of Wall Street,” whatever narcissism and vacuousness afflict the characters, their wealth is not really built on the suffering of millions of people.

Some of this tension is of course built into “The Big Short,” via a climactic conflict for one character and, earlier, a speech from Rickert in which he asks that colleagues curb their enthusiasm about their activities. But for much of the film, the issue just kind of hovers in the background, leaving audiences to puzzle out exactly how to feel about it. And that makes watching the film a wonderfully challenging and complex experience.

At the after-party at AFI Fest, Carell told me how he sees the characters’ actions: “I think you are supposed to be rooting for them and at the same time see the conflict inside of them.” He also said, tellingly, when asked where he came down on Baum, “I think he saw himself as a hero,” leaving viewers to possibly take a different view.

When I volleyed the question to McKay a few minutes later, he offered his own elaboration. “That’s my favorite thing about this movie,” he said. I’m a big believer in not using cartoon heroes. Julian Assange is kind of a creep, but he did some good things. I’m sure if you went back and met Hercules you may find he’s kind of a [jerk].”

McKay might be selling himself, well, short. Flawed heroes are one thing. A movie that actively pulls against itself like this -- that deliberately clouds the question of heroism, that asks us to contemplate the very reasons we root for characters -- is another. There are heroes, there are antiheroes, and there are even heroes who become antiheroes. But it’s far rarer to see people whose ambiguity is so baked in from the start.

One hardly needs an advanced understanding of derivatives to understand the challenge this presents. As delicious as it is to contemplate, this paradox could well make some viewers uncomfortable and might make the movie a tricky sell to mainstream viewers. As an audience, we’re well past the point of needing sympathy and likability from our main characters. But even in the post-”Dark Knight” era, there are still some clear battle lines when it comes to flawed characters. And this movie tangles them up in all kinds of new ways.

Few films out there are able to conjure up such conflicting emotions simultaneously. “The Big Short” has us unsure not only of the characters but of ourselves. It evokes an enthusiastic cheer and then makes us feel uncomfortable for that enthusiasm. Like so much having to do with the financial crisis, it leaves us feeling passionate and angry, but also raw and conflicted.

Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

ALSO:

Why Michael Lewis says Adam McKay gets the Wall Street meltdown right in ‘The Big Short’

What ‘Spotlight’ respects about the church-scandal-breaking journalists and the actors who play them

Will ‘Concussion’ bring Will Smith his third Oscar nomination?