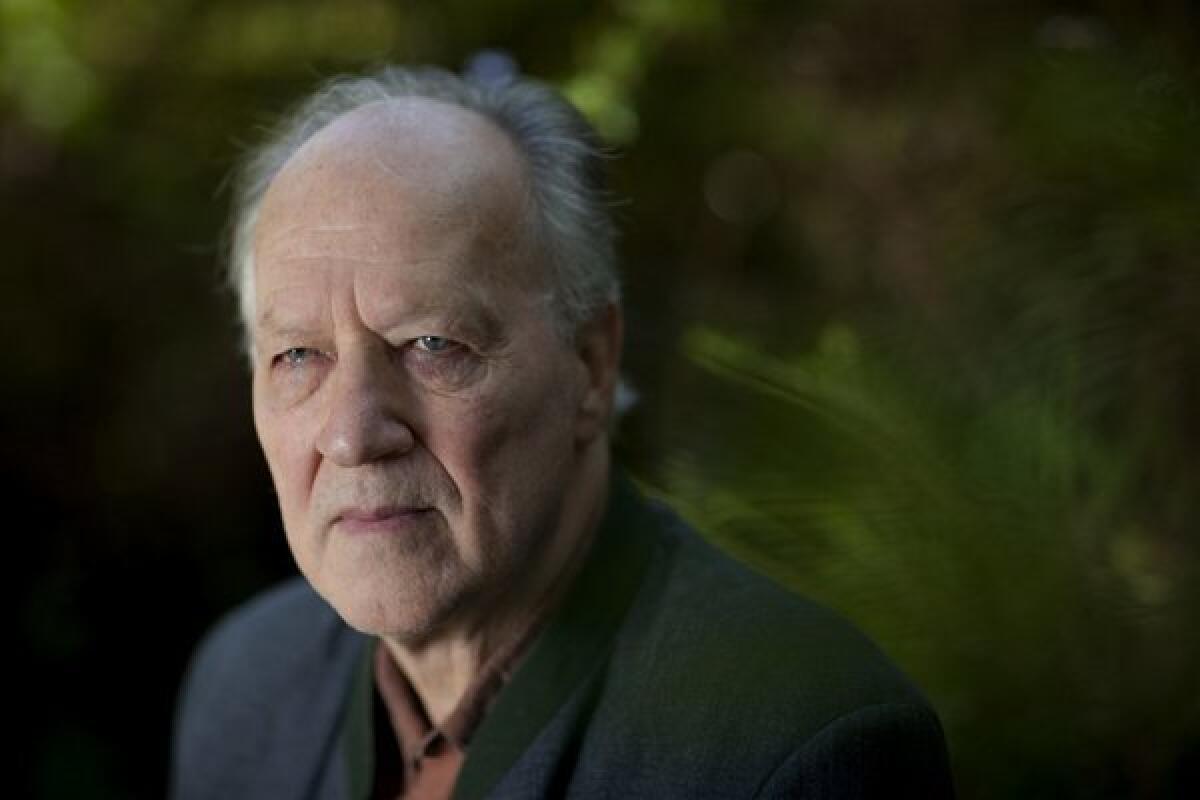

Werner Herzog’s cautionary tale for texters

“From One Second to the Next,” Werner Herzog’s new 35-minute documentary short about victims and perpetrators of catastrophic accidents caused by texting while driving, will be distributed to 40,000 high schools and can be viewed at ItCanWait.com.

How did you come to make “From One Second to the Next”?

I was invited [by AT&T], and it was immediately clear that I should do it and I would like to do it and I was competent to do it.

Why do you think they came to you, and why did you jump at the chance?

I do believe one of the reasons was my previous work “Into the Abyss” [about a murderer on death row], for example — moments of very deep raw emotion, cataclysmic events that came from one moment to the next into the lives of families and irrevocably changed everything.

Did “From One Second” start as an ad campaign before evolving into a 35-minute documentary?

There was always one thing clear — there had to be 30-second spots, and I had no problem to do that because I’m not very much into the life of consumerism — in this case, it’s not for selling a product. It’s a warning that there are dangers in the product. But then I immediately said it would be really good if there were a longer form of it. Everybody expected me to bring the same deep raw emotion into 30 seconds, and you can’t do that fully.

WATCH: Werner Herzog’s ‘From One Second to the Next’ documentary

The film is pretty hard to watch. How hard was it to make?

When I do a film like this and I’m confronted with this raw suffering, I have to perform. My set is a no-cry zone. But when I would stumble out to take a moment of fresh air and there were two vans out there — one for the AT&T people and one for the ad agency, and they had a video connection to what we were filming — and I stumble out and I see in both vans everyone is crying. I had given up smoking long ago, but I would smoke a cigarette just to hang on, then move back in and continue.

How did you choose your subjects?

There was a very, very short time, and we immediately started to look into a collection of cases. Some were immediately excluded because, for example, a young man was willing to talk to us, but he’s in prison right now and prison authorities would not give a permit to shoot in prison. Or some of the key persons in one of these accidents would not talk to us; they’d only allow a lawyer to talk to us. I wanted to do the cases that were most fascinating for me. All of them, due to a chain of coincidences, were in the heartland of America, which I like a lot, although I like the “margins.” I say it in quotes because otherwise I wouldn’t live in Los Angeles.

I was struck by the interviews with the two men whose texting and driving resulted in deaths. How did you get them to open up to you?

I somehow have it in me. I don’t know exactly what it is, but I do believe that doing something like this, you have to know the heart of men.

Did you make them feel as though you weren’t judging them?

No, I took them seriously as two young men who’d caused horrifying accidents with multiple deaths. I think the key was, let’s try to give some meaning to the catastrophe you’ve caused. If, with what you are telling us, one single accident is going to be prevented, everything from now on has a different meaning for you.

The piece on the tragedy in the Amish community was very interesting. Did you try to interview the survivors? Clearly they communicated, at least through the father’s letter of forgiveness.

Yes, and that was very, very remarkable. This reaching out is something of great enormity in my opinion, something wonderful about human beings. The Amish family said very clearly and very politely, we Amish do not appear on television. And I immediately said, “Fine. I respect that. Your lifestyle is just wonderful.” These hard-plowing, wonderful people, I really like them a lot, and you just don’t argue. But they would allow us to have the letter read to the camera, from the father of the three killed children, [sent] out to the perpetrator.

The film has such a clear focus, and it’s such a simple thing. Just don’t text and drive, that’s it. And if one single accident because of that film will be prevented, I can be proud. Maybe statistically the curve will not accelerate as vehemently as it is right now. When you look into the last three years, it starts nearly flat and then it skyrockets. I think it has become more dangerous than drinking and driving. And legislation will start to understand what’s going on, but of course the facts always come first.

You’ve done a number of projects in recent years that deal with death, not just this and “Into the Abyss” but “On Death Row,” “Grizzly Man,” “My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done?” Is death becoming a central concern for you in your work?

Well, I’ve always been very curious about looking very deep into the abysses of the human soul. And when I make films like the series on death row, it’s the real dark recesses. But sometimes it’s a look into a lighter world of our hearts, of our souls, like “Bad Lieutenant” or looking into the dark recesses of prehistory with a film like “The Cave of Forgotten Dreams.” I’ve remained very, very curious.

What happened to the documentary series you were making called “Hate in America”?

It never really got off the ground because everything I wanted to do became prohibitive. When you’re talking to Aryan supremacists, all of a sudden there are threats connected to what you might eventually do, you don’t do a film under the threat or control of people like that. Or in some other cases, prison authorities would not allow me to film.

So what else is coming up?

There are three, four feature film projects, some of them written, some of them not yet written, but I can do it very quickly. Sometimes it depends on how fast you get the finances together.

That’s harder these days, isn’t it?

I’m not in the culture of complaining. There are too many others who are always complaining. I just roll up the sleeves and I do it.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.