Hollywood legend Dick Zanuck: a princeling who earned his stripes

When Dick Zanuck and I had lunch last month, it would’ve been impossible to imagine that the veteran producer would be gone six weeks later. Zanuck, who was 77 when he died Friday at his home in Beverly Hills, looked at least a decade younger and had the energy of an Olympic marathoner. Long before everyone in showbiz became a fitness nut, Zanuck was doing serious workouts, lifting weights, taking long jogs and, in his later years, swimming laps.

Zanuck wasn’t especially vain. He wanted to be in good shape because it gave him more energy for his work, and for him work was life. At a time when most old pros were happy to be off playing golf, Zanuck was always busy, jetting back and forth to London, where many of his recent films were made. When I last saw him, he was making a low-budget thriller in Vancouver after spending much of the past decade producing a string of movies in London with Tim Burton.

As a producer, he had few peers. His career dated to the late 1950s, when he made “Compulsion,” a taut drama about the notorious Leopold and Loeb murder case. The film co-starred Orson Welles, so one of the young Zanuck’s thankless jobs was finding a way to get the night-loving Welles to bed at a decent hour so the actor would make his set call in the morning.

PHOTOS: Richard Zanuck | 1934 - 2012

Zanuck produced more hit movies than you could rattle off in one breath, from “Jaws,” “The Verdict” and “Cocoon” through “Driving Miss Daisy,” “Planet of the Apes” and “Alice in Wonderland.” His producing skills were legend. Even well into his 70s, he was always getting offers from studios to handle their most challenging productions, the studios knowing that if there was a fly in the ointment —a troubled star, a prima donna director — Zanuck would find a way to make the train run on time.

Zanuck was a Hollywood princeling, but no one can say he didn’t earn his stripes. He was the son of fabled 20th Century Fox mogul Darryl Zanuck, who belonged in the Hall of Fame of Difficult and Demanding Fathers. In 1962, when the younger Zanuck was 28, his father made him head of production at Fox, which was on the verge of bankruptcy after losing millions on the catastrophic “Cleopatra.”

One day, nearly a decade ago, Zanuck took me for a walk around the bustling Fox lot, trying to find the tiny bungalow where he’d had his office during the studio’s lowest ebb. It was a time when movie production had ground to a halt. The only money coming in was from the last episodes of “The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis,” the studio’s one hit TV show.

INTERACTIVE: Zanuck’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

“We closed the commissary, the executive office building, everything,” he recalled. “It was just me, a legal guy, a couple of janitors and a guard at the gate. You could literally see the tumbleweeds.”

The lesson Zanuck learned was that nothing lasts forever. He knew that having a famous name meant little unless you could deliver the goods. Even his famous father, the admiral of a fabled movie studio, had run aground. Zanuck spent years turning the place around.

Studios were different then, far more lean and informal than today’s corporate ivory towers. Zanuck told me that most of the decisions were made in a steam room that his father had built in the basement of Fox’s executive offices. Zanuck had only two production executives, a marketing man and someone who handled sales. The staff would stop by for a steam and a drink after work and make decisions.

OBITUARY: Richard Zanuck, Oscar-winning producers, dies at 77

One of the best films Zanuck ever made at Fox was “MASH.” An agent named Ingo Preminger gave Zanuck the book to read on the condition that if he liked it, Preminger could produce it. Zanuck read it that night and called Preminger the next day. “Sell the agency,” he told him. “You’ve got an office on the third floor. We’re making the picture.”

But as Zanuck often said, nothing lasts forever, especially in the capricious environs of Hollywood. Not long after “MASH” became a game-changing hit, Zanuck lost his job, fired by his own father. His mistake, as he later explained, was that when the studio needed to trim staff, Zanuck refused to make any personal exceptions and laid off his father’s girlfriend. It caused a rift that resulted in the younger Zanuck’s ouster.

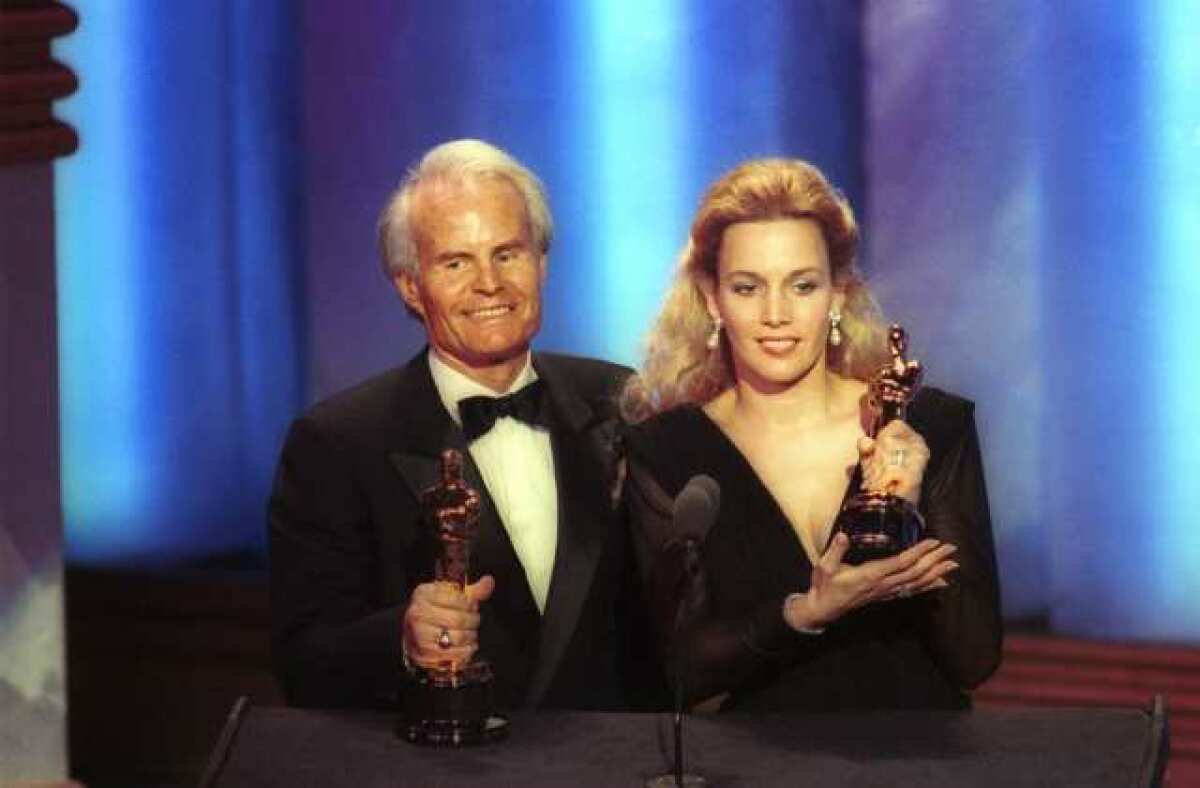

No matter. Zanuck put out his shingle as a producer, starting out as a partner with David Brown — one of their first successes was “The Sting,” for which they took a “presented by” credit. After a while, Zanuck struck up a new partnership with his wife, Lili Fini Zanuck, joined in later years by his son, Dean Zanuck.

He had a good eye for a story and an even better one for talent. In the early 1970s, he met a gawky young filmmaker named Steven Spielberg who desperately wanted to make a road picture called “The Sugarland Express” at Universal Pictures. The movie had been put into turnaround, but Zanuck, impressed by the kid’s moxie, went to see then-Universal chief Lew Wasserman and lobbied for the film.

In those days, if a producer had already pulled a few aces like “The Sting” out of the deck, he could persuade a studio head to take a chance on a risky bet. Still, Wasserman seemed to have little interest, predicting that the film would play to empty theaters. Talk moved on to other projects. Finally the meeting came to an end. Zanuck loved telling people what Wasserman said, because it perfectly illustrated how decision-making in Hollywood had changed from then to now.

“As I got up to leave, Lew said, ‘When do you think you could start?’ I said, ‘Start what?’ And he said, ‘Dick, I’m not making this deal with you because I think I know more about producing than you do. Go make the picture. Why would I hire you if I didn’t trust your judgment?’”

Wasserman was right — “Sugarland Express” didn’t make a dime. But Spielberg never forgot that the studio gave him a big break, so when it came time to make his next film, “Jaws,” he and Zanuck made it at Universal. It became one of the studio’s biggest all-time hits and the beginning of a decades-long relationship between Universal and the filmmaker.

Zanuck went on to work with all sorts of great directing talent, including Ron Howard, Bruce Beresford, Walter Hill, Sam Mendes and Burton. The filmmakers knew that when Zanuck was around, they’d be safe from unwanted interference. On their first film together, Spielberg asked Zanuck if he would really be his producer. Zanuck replied: “Think of me as your bodyguard.”

As a producer, Zanuck made Hollywood a safe place to do good work, which is perhaps why he never had to beg for a job. If you were going to make a costly, high-risk movie, Dick Zanuck was the man you wanted in the producer’s chair. It meant the movie was going to be in good hands.

RELATED

Is it time for Woody Allen to make a movie in Israel?

Is raunchy R-rated ‘Ted’ really America’s favorite family film?

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.