In more than three decades as a reporter, I have been fortunate enough to witness more than my share of history, from elections to wars to most everything in between.

So I’m a little embarrassed to say I have almost no memory of my first brush with history — the night Bob Dylan, the 2016 recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature, went electric and shook up the music world.

It was July 25, 1965, and I was a 13-year-old kid at a summer camp in Sturbridge, Mass. The folk-music era was at its height and somehow a group of campers and counselors wound up at the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island.

Newport was the Woodstock of the pre-Woodstock years, a homing beacon for singers and fans who saw themselves as avatars of peace and change as Vietnam, civil rights and other social issues exploded around us.

We camped somewhere on the festival grounds, a green spit of land in a state park with gorgeous views of the ocean and fierce mosquitoes. Did we bring our guitars? Of course.

The bill that weekend offered an array of acoustic greats and not-so-greats. Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Lightnin’ Hopkins and others played, sang and held workshops. And Bob Dylan — then a “protest singer,” now a Nobel laureate — was the headliner.

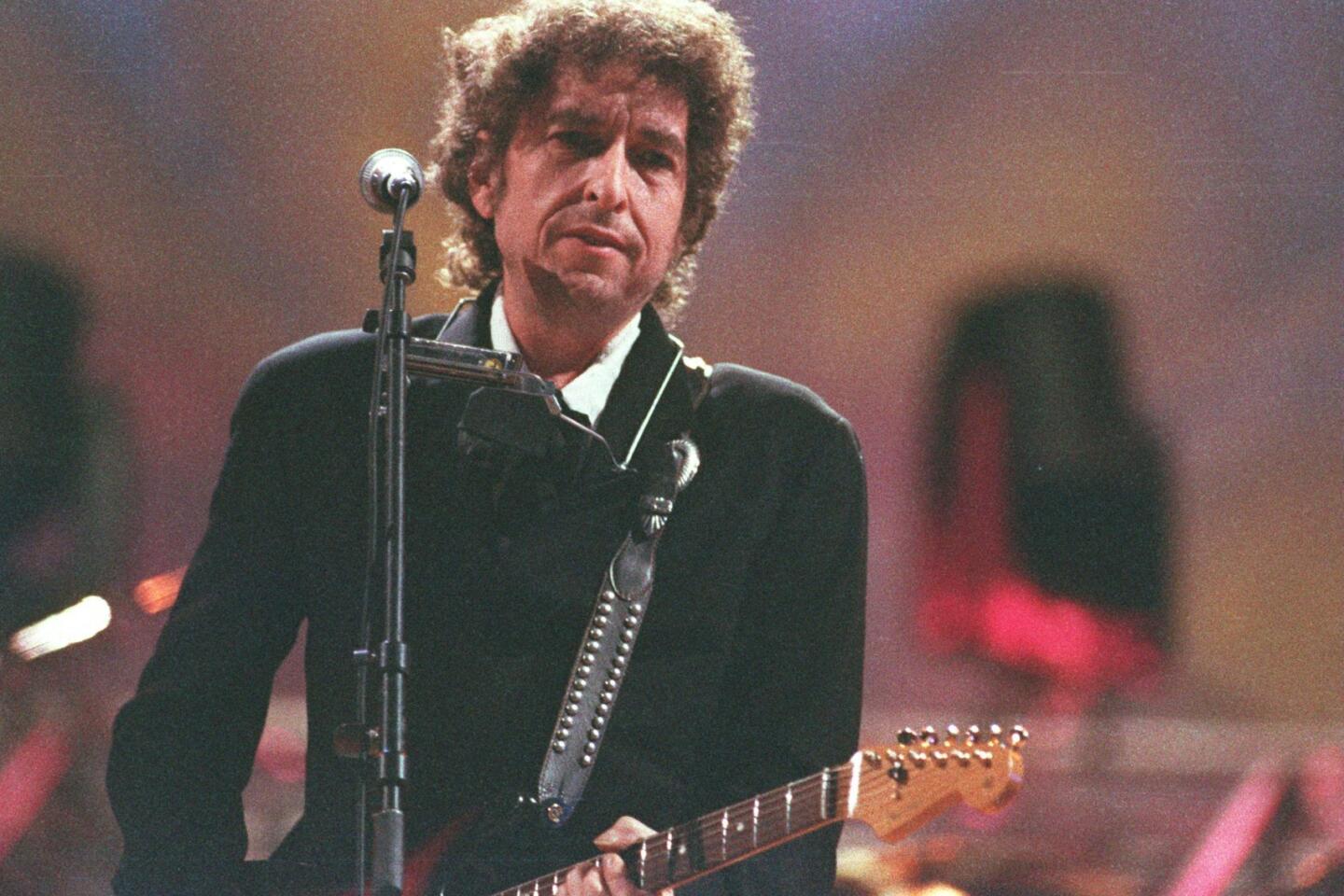

1/18

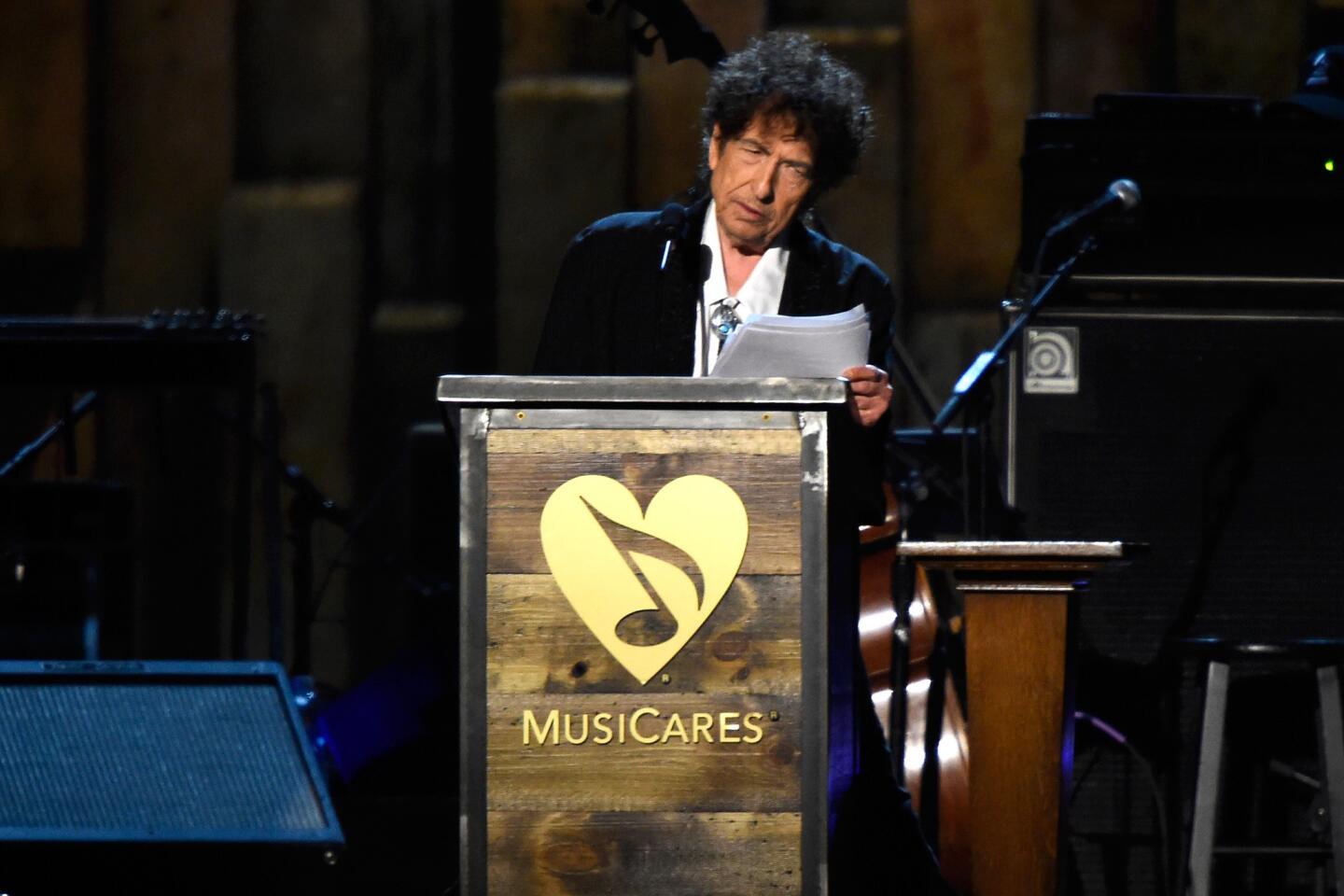

Bob Dylan’s lengthy career is difficult to sum up. The restless and prolific innovator has sold more than 100 million albums, won Grammys, Golden Globes and Oscars and is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Check out highlights of his legendary life. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

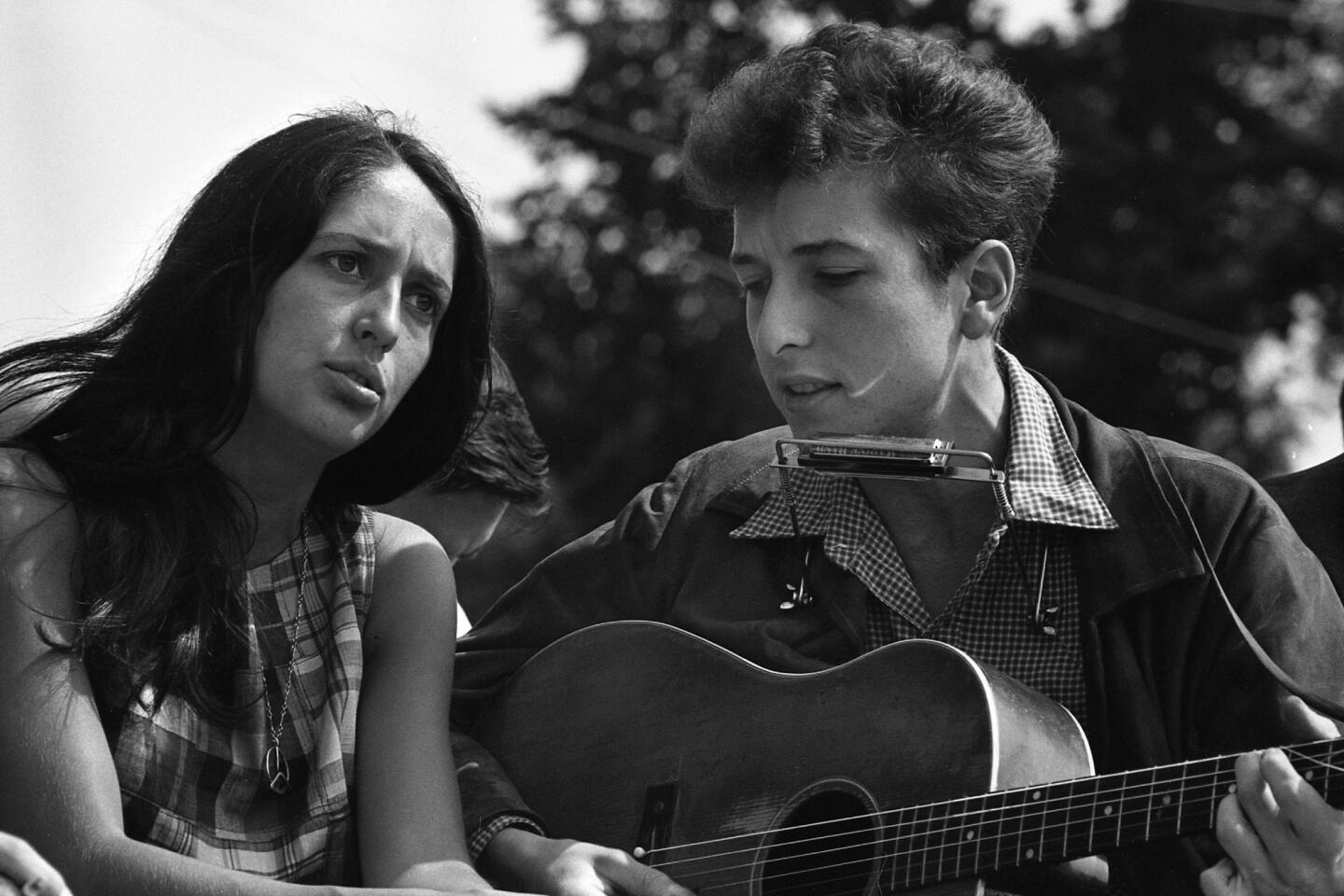

2/18

Political folk singer Joan Baez was a highly influential collaborator with Dylan in his early career. They’re pictured performing during the March on Washington civil rights rally on Aug. 28, 1963. (Rowland Scherman / Getty Images)

3/18

After recovering from a near-fatal 1966 motorcycle crash, Dylan regrouped, playing with a backing band soon to be known as the Band. Eschewing touring, they instead recorded dozens of songs in widely bootlegged sessions later known as “The Basement Tapes.” They are shown performing Jan. 20, 1968, in New York City’s Carnegie Hall. (Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images)

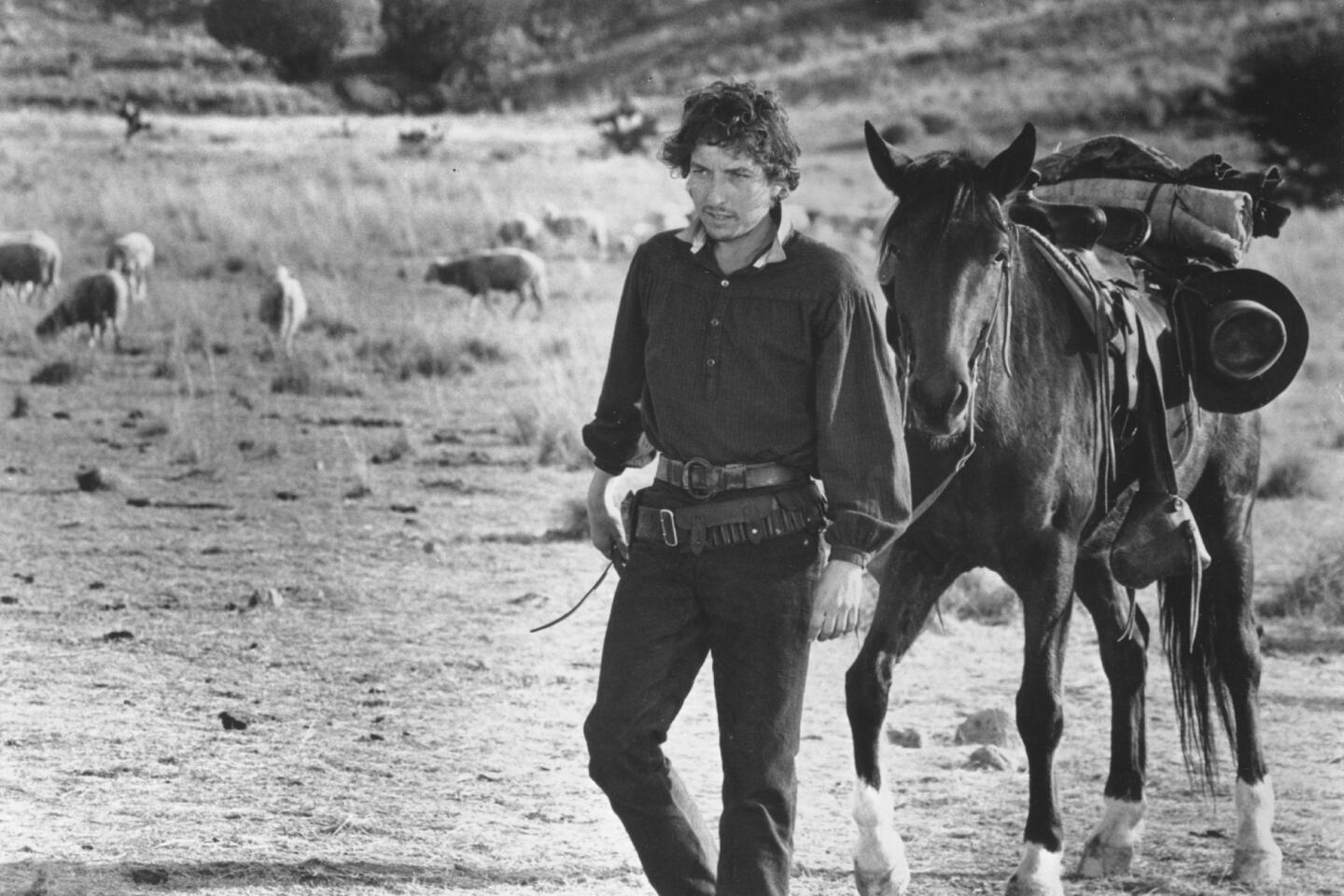

4/18

Bob Dylan appears in a film still for “Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid” (for which he also did the soundtrack) which was released in May 1973 and filmed in Durango, Mexico.

(Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images) 5/18

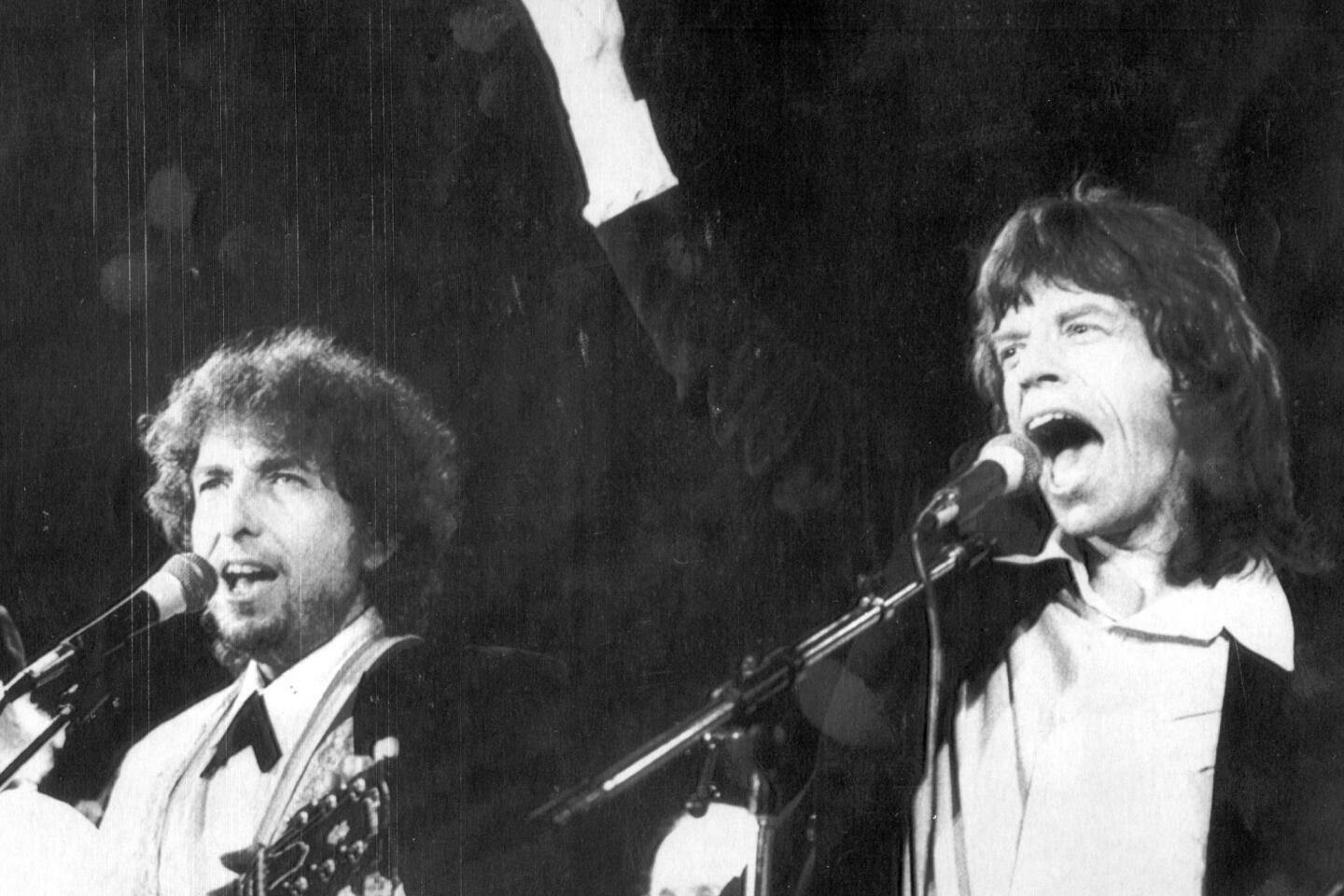

In 1988, Dylan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. After the ceremony, he performed with the Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger, right. (Vince Compagnone / Los Angeles Times)

6/18

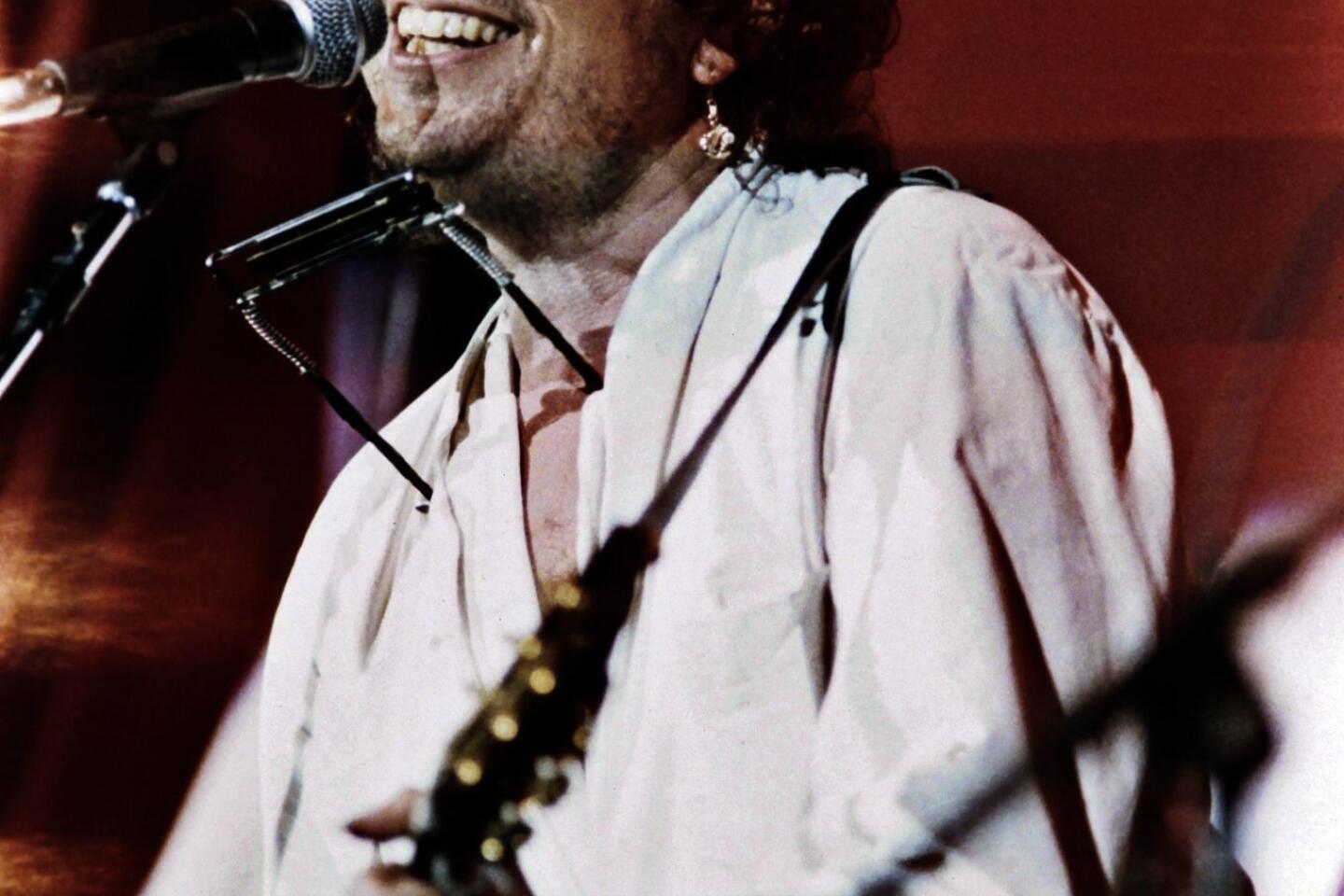

Bob Dylan performs at the John F Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia during the first international live aid concert against hunger in Africa on July 13, 1985.

(Micelotta Frank / AFP/Getty Images) 7/18

In 1994, Dylan performed at the 25th anniversary of Woodstock in upstate New York. He had rejected an invitation to play at the original 1969 fest, choosing instead to appear at the Isle of Wight festival in England on Aug. 31, 1969. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

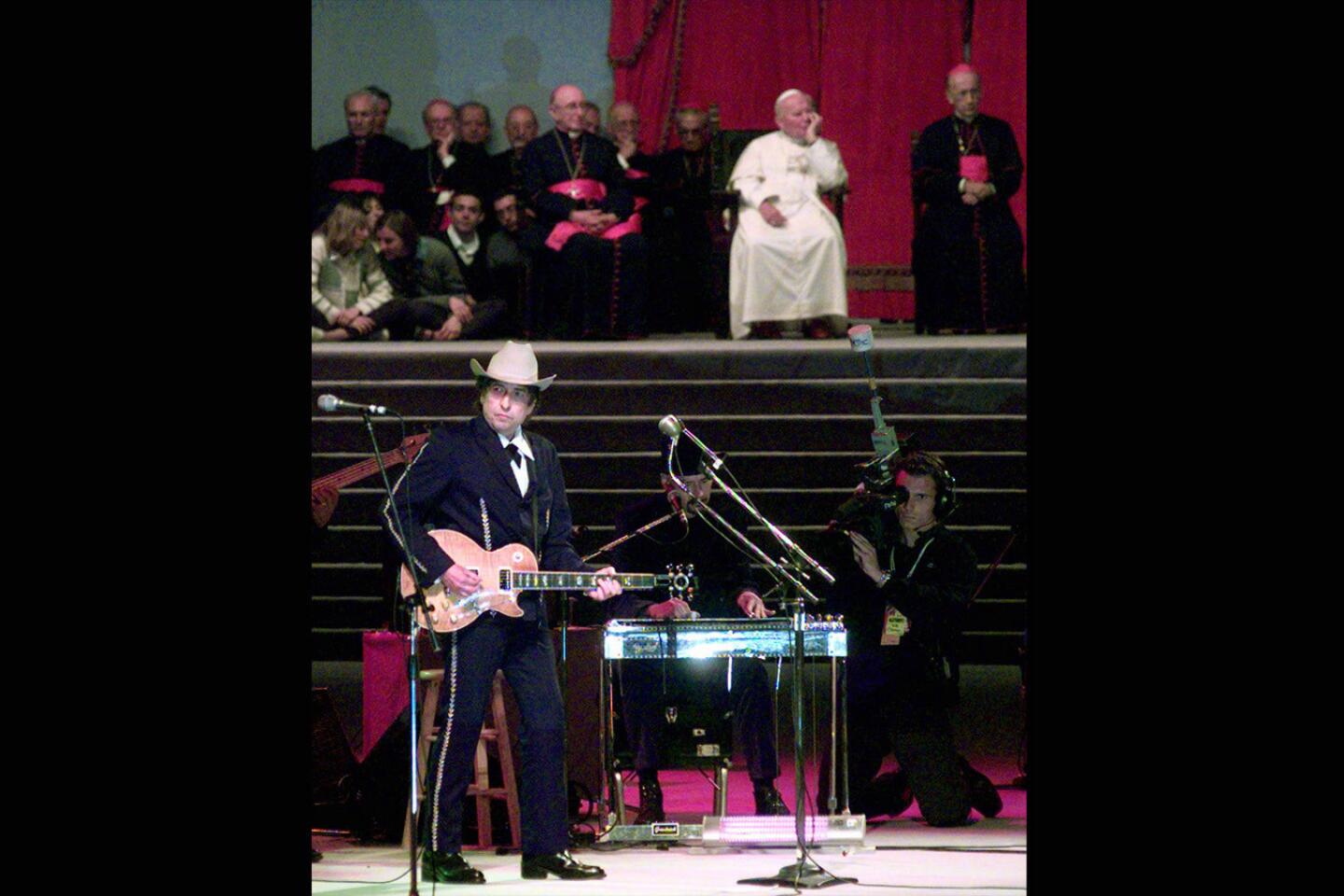

8/18

Dylan performed one of his best-known songs, “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” in front of Pope John Paul II in Bologna, Italy on Sept. 27, 1997, before an estimated crowd of 300,000 (Luca Bruno / AP)

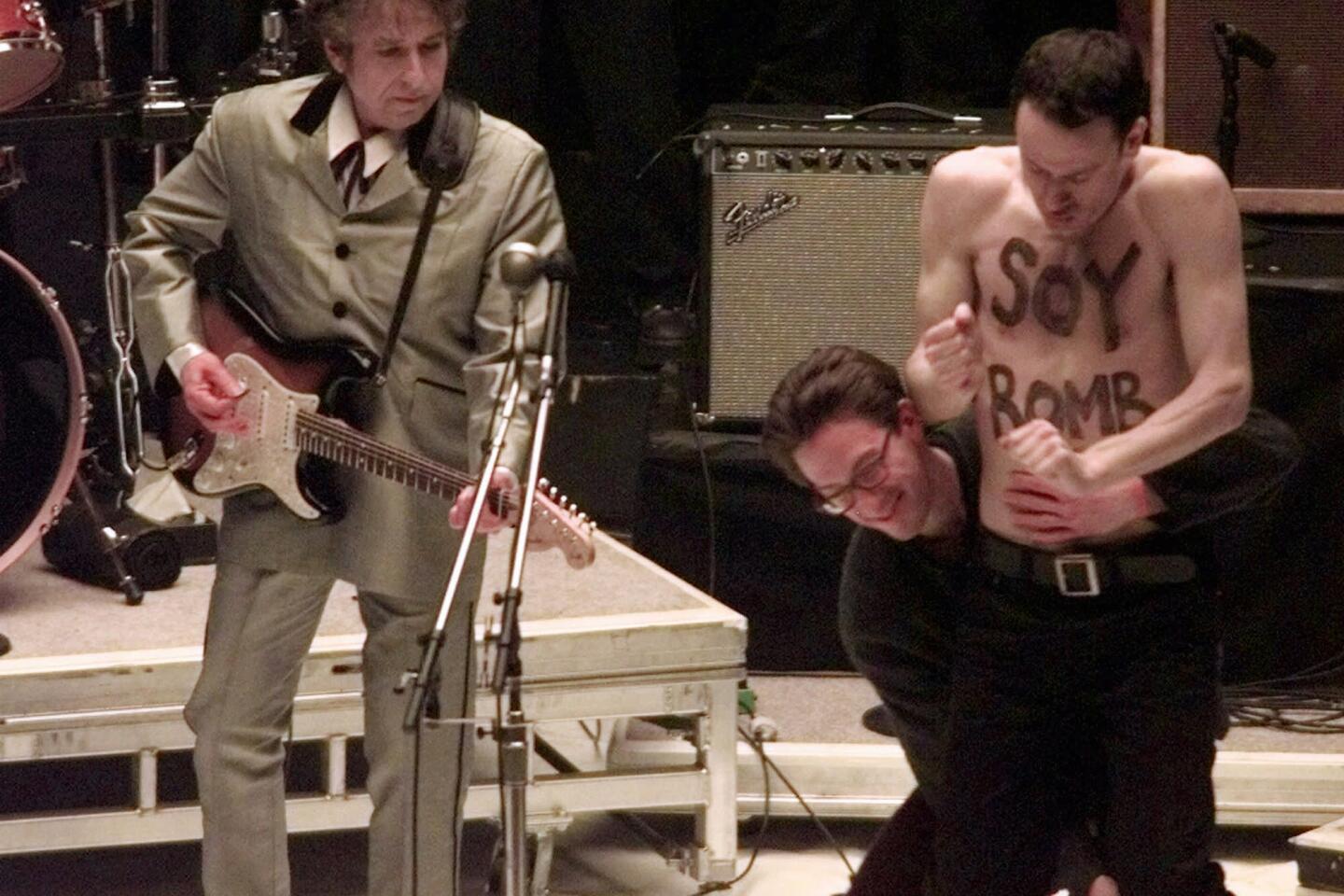

9/18

While performing the song “Love Sick” at the 1998 Grammys, Dylan was interrupted by performance artist Michael Portnoy, with the words “Soy Bomb” painted on his chest. (Mark Lennihan / AP)

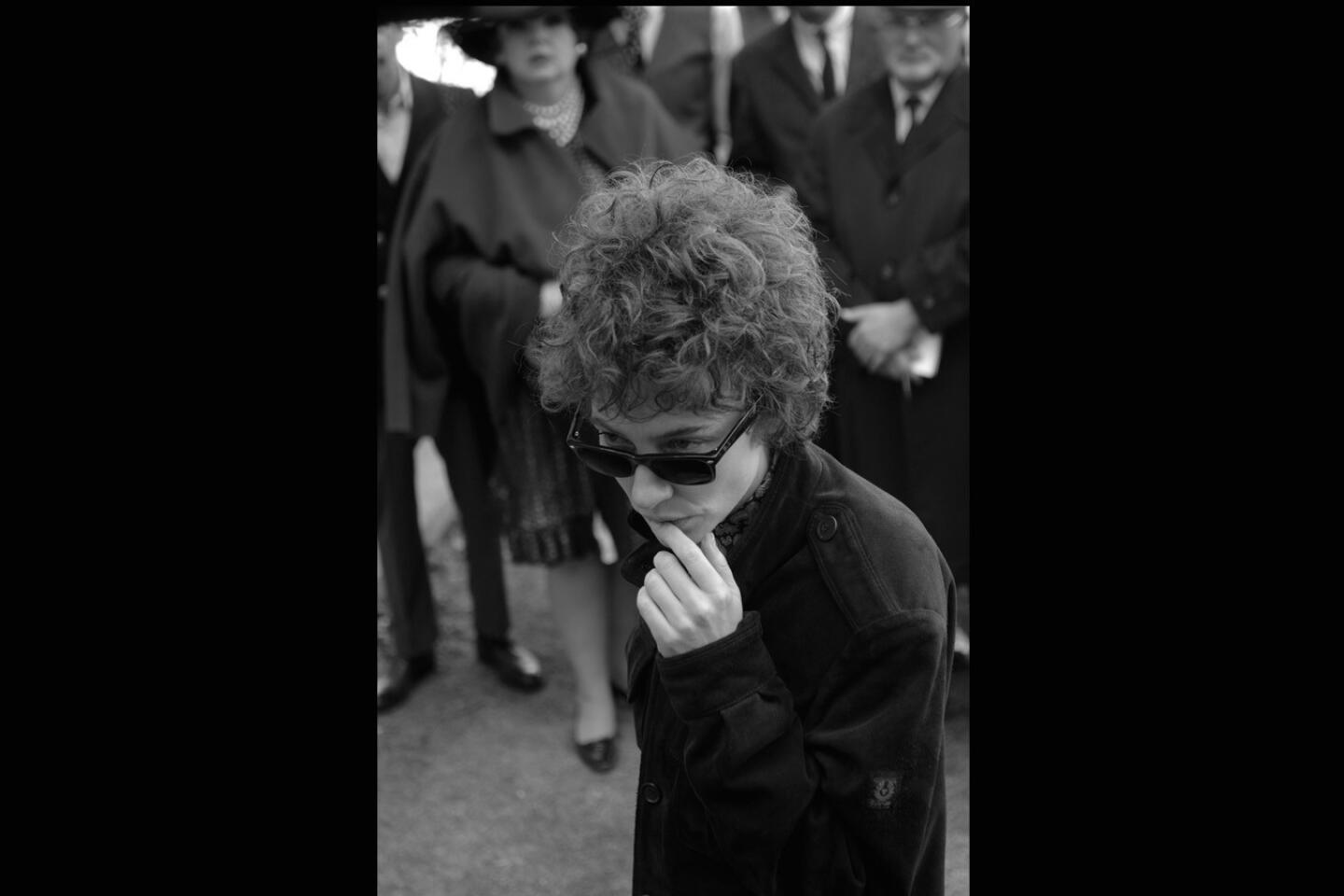

10/18

Dylan has been married twice and has six children. His son Jakob Dylan, center, is the lead singer for the rock band the Wallflowers and a solo artist. (Patrick Downs / Los Angeles Times)

11/18

In 2002, Dylan returned to the Newport Folk Festival for the first time since 1965, when he had famously shocked fans by strapping on an electric guitar. (Michael Dwyer / AP)

12/18

In 2006, director Todd Haynes released the film “I’m Not There,” in which different actors -- including Richard Gere, Heath Ledger, Christian Bale and Cate Blanchett, pictured -- play incarnations of Dylan at various phases of his public and private life. (Jonathan Wenk / AP)

13/18

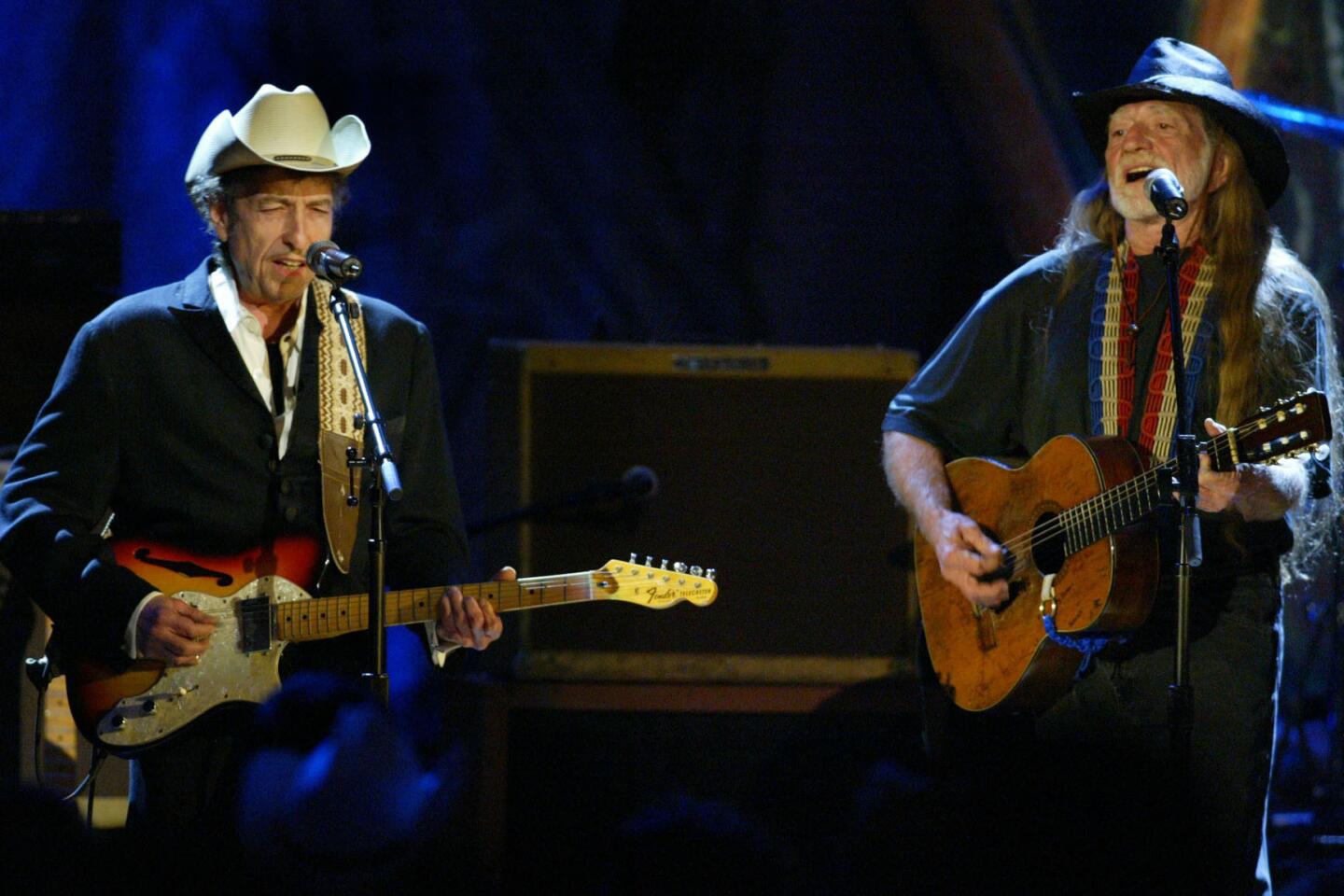

Willie Nelson, right, and Dylan performed together at Willie Nelson and Friends’ “Outlaws and Angels” concert at the Wiltern in Los Angeles on May 5, 2004. (Lori Shepler / Los Angeles Times)

14/18

President Barack Obama, background, presents the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Bob Dylan on May 29, 2012.

(Mandel Ngan / AFP/Getty Images) 15/18

Dylan -- seen at Les Vieilles Charrues Festival in Carhaix, France, in December 2013 -- continues to perform on what’s been dubbed “The Never Ending Tour.” (David Vincent / AP)

16/18

Among the many recent tributes inspired by Dylan was 2014’s album “Lost on the River: The New Basement Tapes.” Participants included Jim James, left, Rhiannon Giddens, Marcus Mumford, Taylor Goldsmith and Elvis Costello. (Drew Gurian / Invision / AP)

18/18

People look at books by Bob Dylan who was announced the laureate of the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature at the Swedish Academy in Stockholm, Sweden, on Oct. 13, 2016.

(Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP/Getty Images) His songs defied convention. So did his nasal voice and enigmatic verse. We knew “Blowing in the Wind” and “Masters of War” and “Mr. Tambourine Man.” We knew our parents didn’t understand him. So we pretended we did.

His half-electric “Bringing It All Back Home” album had been released that spring, and our tiny, tinny transistor radios were just starting to play his latest mesmerizing song, “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Dylan apparently appeared on the main stage after Cousin Emmy and the Sea Island Singers, whoever they were. It was already dark and we were probably tired, mosquito-bit and whining. Maybe we were still at the workshops or at another stage.

But I have no real memory of watching Dylan pick up his Fender Stratocaster, tune endlessly with guitarist Mike Bloomfield and keyboardist Al Kooper, and start bleating into the microphone.

I’ve read that he was introduced on the main stage by Peter Yarrow of Peter, Paul and Mary fame, and the performance was short, loud and brutish. Dylan and his band played only three electric songs: “Maggie’s Farm,” “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Phantom Engineer.”

Films have been shot and books written about whether the audience really booed Dylan for playing his first electric set in public and forever betraying the cause of folk music.

My guess, having heard Dylan play many times since, is they were booing the brief set and the crappy sound system. Seeger supposedly threatened to pull the plugs because it was so loud.

But if that was history, I missed it.

ALSO

Bob Dylan: ‘The Homer of our time’

Critics wonder if Bob Dylan really needs a Nobel Prize

Bob Dylan, interpreter: Seven of the artist’s greatest covers

Celebrating Dylan’s late career work, when he started getting obsessed with death

‘He’s a historical magician’: Two professors on why Bob Dylan deserves the Nobel Prize