Charles Manson’s life as a failed musician, Beach Boys hanger-on and mediocre songwriter

- Share via

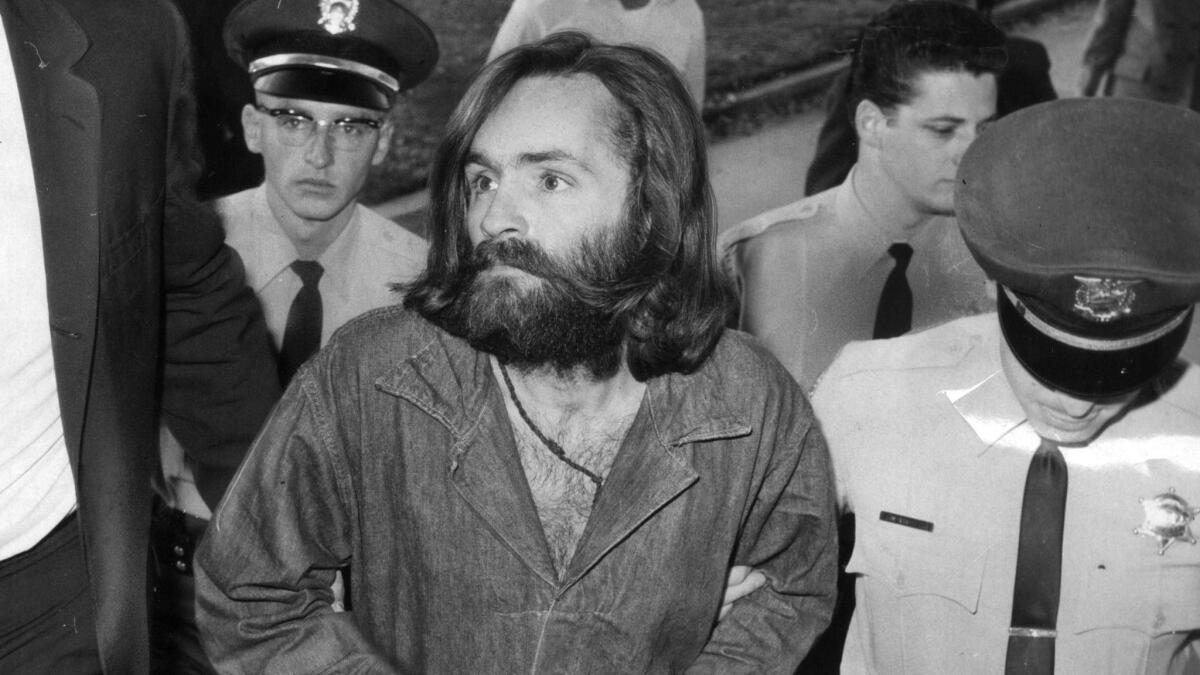

Starting in the 1970s, not long after Charles Manson directed his followers to murder seven people over two bloody nights in Los Angeles, the convicted killer’s music and notoriety fueled a small underground industry.

The allure was centered on Manson’s only album, recorded in Los Angeles in 1967 and ’68 and issued a year after the 1969 murders. Manson, it turns out, was a failed folk rock artist who desperately sought the attention of a Los Angeles music scene then thriving in the studios, labels and clubs along Sunset Boulevard.

He didn’t get it, and that rejection by insiders including the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson and record producer (and Doris Day’s son) Terry Melcher helped ignite Manson’s rage.

Called “Lie: The Love and Terror Cult,” Manson’s album was issued on an imprint branded Awareness and featured 14 Manson originals, including “Garbage Dump,” “Sick City” and “Look at Your Game, Girl.”

Songs from it have been covered by bands including Guns N’ Roses and the Lemonheads, and punk singer-writer-DJ Henry Rollins produced some Manson jailhouse recordings that have never been officially released.

Most notably, “Lie” features a Manson-penned song titled “Cease to Exist,” which became the center of a dispute between him and the Beach Boys after the band reworked the song, changing lyrics, the tone and renaming it “Never Learn Not to Love.”

Manson had barged his way into the world of Beach Boy Dennis Wilson after the musician picked up two women hitchhikers from Manson’s posse. For a while he and members of the so-called family lived at Wilson’s Sunset Boulevard home (which was formerly Will Rogers’ hunting lodge). Manson even lobbied to be on the Beach Boys’ imprint, Brother Records.

During a 2016 interview with the Wall Street Journal, the Beach Boys’ Mike Love recalled going to a dinner party with bandmate Bruce Johnston at Dennis Wilson’s house. The Manson family was there and after dinner, he said, most took LSD.

“We were the only ones with clothes on,” Love, who declined the drug, said of his and Johnston’s arrival. “It was quite unusual.”

The Beach Boys issued “Never Learn Not to Love” as the B-side to “Bluebirds on the Mountain” in early December 1968. Manson was said to be furious that the Beach Boys hadn’t credited him for his work, and that they’d changed some of his precious words. “Submission is a gift,” Manson’s version goes. “Go on, give it to your brother / Love and understanding / Is for one another.”

Within months of the release, Manson’s family had stolen some of Dennis Wilson’s gold records, totaled his Mercedes and cost him a reported $100,000.

The murders of victims including Sharon Tate, Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca occurred in the summer of 1969. The No. 1 record at the time was Zager & Evans’ one-hit wonder “In the Year 2525.”

Manson and many family members were arrested in October of that year. Jury selection into his role in the murders began in June 1970.

It was around then that the owner of Awareness, Phil Kaufman, pressed Manson’s album. Kaufman was a famous tour manager, perhaps best known for absconding with the body of the late country rocker Gram Parsons after he died at the Joshua Tree Inn — and then lighting fire to the artist and his coffin in the desert.

We made a deal. [Manson] said, ‘Put out my record and you can have all the rights to my music.’ So I did.

— Producer and road manager Phil Kaufman

Kaufman came to put out “Lie” after meeting Manson in the mid-1960s at the Terminal Island federal correctional facility near the L.A. harbor. Kaufman was in prison for a felony marijuana conviction, and Manson was jailed for crimes including forgery and pimping.

After Manson was arrested in the murders but before being convicted for his part of them, recalled Kaufman in a 2013 interview, “we made a deal. [Manson] said, ‘Put out my record and you can have all the rights to my music.’ So I did.”

Kaufman remembered pressing a few thousand copies — but said that “half of those were stolen by the family when they broke into my house. They tried three more times, and the last time I chased them off with a gun, so I never saw them again.”

A year later a Spanish label called Movieplay issued a European version titled “12 Canciones Compuestas y Cantadas por Charles Manson.” The noted avant-garde label ESP-Disk put out an edition in the early 1970s, and the notorious imprint Come Organization issued a version in 1981. During the compact disc era, the record is said to have sold thousands of copies.

The mid-1980s saw the release of a record of songs by Manson’s followers called “The Manson Family Sings the Songs of Charles Manson.” Recorded in 1970 and featuring home-recorded renditions of Manson’s unpublished songs, the album features contributions from family members including Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, Sandra Good and Steve “Clem” Grogan.

By law, Manson wasn’t allowed to collect royalties — those are supposed to go to victims’ families — but a number of well-known and respected artists have used Manson’s music and image for shock value, ensuring his songs are not totally forgotten.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, the Manson family’s mystique fueled a mythology that inspired art by Sonic Youth, Front Line Assembly, the punk artist Raymond Pettibon and his brother Greg Ginn’s band Black Flag.

“Cease to Exist” has been covered by artists including Redd Kross, the Lemonheads and G.G. Allin. Guns N’ Roses recorded “Look at Your Game, Girl” for its record “The Spaghetti Incident?”

Trent Reznor made his classic album “The Downward Spiral” at the Benedict Canyon home where Manson’s followers murdered Tate, who was eight months pregnant at the time.

Reznor’s seeming glorification ended during a random encounter with Tate’s sister. According to Reznor in a 1997 interview with Rolling Stone, she said, “’Are you exploiting my sister’s death by living in her house?’ For the first time the whole thing kind of slapped me in the face,” Reznor said, adding that “I don’t want to be looked at as a guy who supports serial-killer bull ….”

And long removed from teenage rebellion, Redd Kross member Jeff McDonald expressed regret for covering Manson to MTV in 2012. The band’s take on “Cease to Exist” appears on 1982’s “Born Innocent,” and McDonald said the move was largely done to annoy the band members’ parents.

“It was more just the aesthetic and we did it and dropped it after a while. But we’re associated with it, which is kind of a bummer,” McDonald told MTV, adding, that he eventually concluded that “we can’t perpetuate this thing.”

Manson’s “Lie: The Love and Terror Cult” is currently available on all the major streaming services through a deal with ESP-Disk, which was approached by Awareness Records’ Kaufman for better distribution and has since reissued it on CD and vinyl.

This reporter’s opinion: The record’s not very good, filled with drug-addled, period-piece rants about loss of ego, the comfort of home (“And as long as you got love in your heart / You’ll never be alone”) and eating food from trash cans (“I don’t even care who wins the war / I’ll be in them cans behind my favorite store”).

But then, serial killer John Wayne Gacy’s clown paintings were bad too. That didn’t stop weirdo collectors from snatching them up.

In the ‘90s when I worked in a St. Louis record store, we couldn’t keep “Lie” in stock. Young, impressionable punks — dudes, mostly — lapped it up. They also bought records by hardcore band Ed Gein’s Car and songs about the New York killer known as the Son of Sam and Utah murderer Gary Gilmore.

Minus Manson’s background, all evidence suggests the cult leader didn’t have the talent to make it in the business.

“Mechanical Man” features this god-awful series of couplets:

I had a little monkey / And I sent him to the country / And I fed him ginger bread / Along came a choo choo/And knocked my monkey koo koo / And now my monkey’s dead.

When it comes to Manson and the murders, silver linings are hard to come by. But at least his decades in prison had one positive: his chance to release more music ceased to exist.

For tips, records, snapshots and stories on Los Angeles music culture, follow Randall Roberts on Twitter and Instagram: @liledit. Email: randall.roberts@latimes.com.

ALSO

Charles Manson, mastermind of 1969 murders, dies at 83

Where are they now? Charles Manson’s ‘family,’ decades after horrific murders

Quentin Tarantino movie about Manson era set to receive an $18-million California tax credit

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.