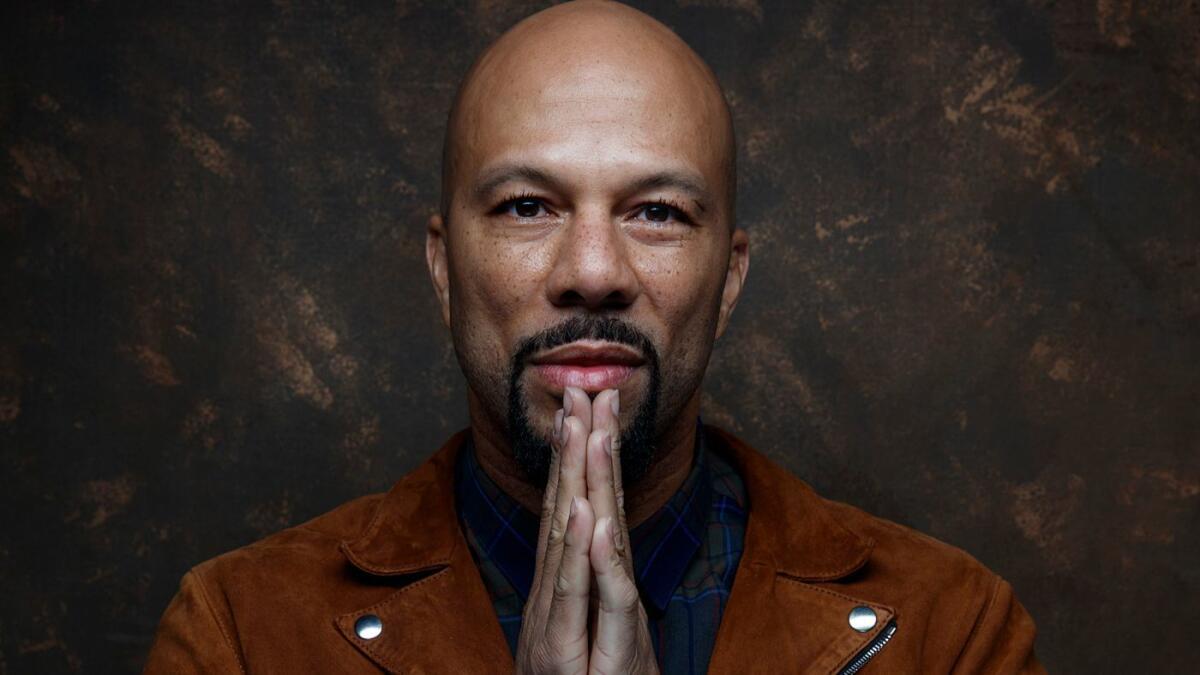

Hip-hop gamechanger Common, rap’s unofficial ambassador

Common and hip-hop have always had a symbiotic relationship.

As a young rapper from the Southside of Chicago, hip-hop provided him with a path toward notoriety, success and empowerment. In return, Common elevated the style that elevated him with an eloquence, soul and activism seemingly channeled from an earlier era.

Today, the artist and hip-hop have reached heights no one could have imagined back in the early 1990s when the artist then known as Common Sense first stepped up to a mic.

Hip-hop at 45 is no longer a subculture, but a cultural driver, influencing what we watch, what we wear and how we speak (blame Jay-Z for your insufferable uncle’s overuse of the word “chill”).

Common at 45 is an internationally recognized figure who’s one Tony Award away from becoming an EGOT — Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, Tony winner — and that’s not counting his Golden Globe. He’s renowned for his roles in films such as “Selma,” “Barbershop” and “Suicide Squad”; his lasting influence on hip-hop culture, and most recently his recurring role in the new Showtime series he and Lena Waithe executive produce, “The Chi.”

With Common as hip-hop’s unofficial ambassador, its influence has been present in a White House poetry reading, a Gap “holiday in the hood” commercial, childhood reading programs and indelible Oscar and Golden Globes speeches.

At the 2015 Academy Awards when the rapper and singer John Legend accepted the award for “Glory,” the original song they wrote and performed for “Selma,” Common followed up his show-stopping Golden Globes “I am” speech with a heartfelt message, rooted in poetic wordplay, that brought the room of jaded Hollywood types to tears (and their feet).

“Recently, John and I got to go to Selma and perform ‘Glory’ on the same bridge that Dr. King and the people of the civil rights movement marched on 50 years ago,” Common told the packed venue.

“This bridge was once a landmark of a divided nation, but now is a symbol for change. The spirit of this bridge transcends race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, and social status. The spirit of this bridge connects the kid from the Southside of Chicago, dreaming of a better life, to those in France standing up for their freedom of expression to the people in Hong Kong protesting for democracy. This bridge was built on hope. Welded with compassion. And elevated by love for all human beings.”

Common, born Lonnie Rashid Lynn Jr., touched nearly everyone in the audience, from Chris Pine to Oprah Winfrey and countless others watching at home.

And now he’s the one making the films.

Common founded his own Freedom Road Productions after the Oscars to promote more diverse narratives on the small and big screen.

Today that means “The Chi,” a Showtime series about life, love and yes, tragedy, on the Southside of Chicago. Tomorrow it’s the Starz series adaptation of the African American comic book hero, “Black Samurai,” that he’s co-producing with RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan.

If you could point to one aspect or culture that has changed the world, I pick hip-hop.

— Common

“If you could point to one aspect or culture that has changed the world, I pick hip-hop,” said Common while on set in Chicago for “The Chi.” “It’s elevated the voices of those who are unheard and overlooked and looked down upon. And it has given us a lot of voices… Now the world connects with us in so many different ways.”

On Sunday, the three-time Grammy winner could pick up a fourth Recording Academy award — the visual media honor for “Stand Up for Something,” written for “Marshall,” the Reginald Hudlin-directed film about Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Supreme Court justice. It will be a night in which the top prize categories are for the first time dominated by rap artists.

Jay-Z is up for eight awards, including album, record and song of the year; Kendrick Lamar has seven nominations, and Childish Gambino, Khalid, No I.D. and SZA each have five.

While the Recording Academy added a rap album category in 1995, it’s been a holdout when it comes to reflecting generational shifts and tastes in its top prizes. Millennials, after all, were raised as much on Tupac Shakur and Eminem as they were Britney Spears and ’N Sync.

Common was more thoughtful and eclectic in his music career than blockbuster crossovers like Ludacris; still, he’s one of a select club of hip-hop artists who survived the fickle turns of the rap and music industries with his self-respect — and the respect of the public — intact.

And like any urban artist who’s crossed over, he’s also weathered the fear and scathing criticism that come with getting, as the saying goes, “white famous.”

And like any urban artist who’s crossed over, he’s also weathered the fear and scathing criticism that come with getting, as the saying goes, “white famous.”

When Common was invited to read poetry at the White House in 2011 upon invitation from then First Lady Michelle Obama, Sarah Palin seized upon the moment. On Fox News, she questioned why an artist who glorified killing cops (he didn’t) would be invited to the president’s home.

“I was more surprised by the fact she knew who I was,” Common said and laughed. “It’s the political game that people play, though…. A [month before] they had me talking about the community work I’ve done. Then it’s like, ‘This guy is the vilest rapper.’ ”

Today such a flap would be laughable in an era when “Hamilton” swept the Tonys, “Atlanta” the Emmys, and Jay-Z and Beyonce are not just music stars but business icons.

Common — the son of an educator and ABA basketball player — came of age with hip-hop, entering his teens when N.W.A was shocking parents and moral crusaders with songs such as “… tha Police.”

His debut album, 1992’s “Can I Borrow a Dollar,” made small waves throughout the underground rap world for its low-key, introspective approach. Throughout the decade, his style ran counter to the gangsta rap that was climbing the charts and causing panic among parents in white suburbs.

Common rapped in a style closer to spoken word, over a sound many would later dub neo soul. Essentially, jazz and R&B influences from an earlier time. By the time Common’s two major-label albums — “Like Water for Chocolate” and “Electric Circus” — were released in 2000 and 2002, their inspiring nature hit a nerve with audiences who were tired of the violence that had taken some of hip-hop’s brightest stars. Common’s career took off as hip-hop continued to break down major color and cultural barriers.

I felt a responsibility to be a voice for the people of Chicago, to represent their humanity.

— Common

“Hip-hop has endorsed from the beginning, ‘Be yourself,’ ” says Common. “You could talk the way you want to talk. People who were successful in hip-hop could go into a corporate office and still talk in a language they talk,” he adds. “Movies put a hip-hop artist in there because of the flair and the energy they bring. They had talent and character that Hollywood hadn’t seen. Now a lot of these networks and streaming services are allowing the voices to come through. And nobody is saying ‘No, this is too black.’ ”

“The Chi” weaves music of local Chicago artists such as Chance the Rapper, NoName and B.J. the Chicago Kid throughout the series, as well as other forms of music. It’s a combination that reflects the wider appeal of the critically acclaimed series.

But it is hip-hop specifically that brought Common to a place where he had the power and influence to sell and promote a narrative about the place in which he and Waithe grew up. A place that’s rarely had the chance to define itself in the media.

“I felt a responsibility to be a voice for the people of Chicago, to represent their humanity,” says Common. “We are human beings and that’s something many people don’t get to experience or witness because they hear about Chicago through its violence. And that is exploited by political leaders like [Donald] Trump or other people who’ve used it as an example of why we should have federal marshal laws that are tough on crime. But we have a duty to make sure we tell the stories of these human beings.”

And as Common points out, it’s unlikely a show like “The Chi” would have ever seen the light of day if hip-hop hadn’t bridged racial — and musical — divides.

“We broke through and it’s a new day, a new time,” he says. “America is better for it. And so am I.”

https://twitter.com/lorraineali

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.