Mexico’s N.A.A.F.I record label is changing club culture around the globe

Museo Jumex, the new spiky-roofed contemporary art museum in Mexico City, is a beacon for a global cultural capital. Nestled between billionaire Carlos Slim’s own glittery private-collection monument Museo Soumaya and rows of gleaming new condo towers, the space is analogous to L.A.’s Broad Museum.

For six months in 2015 and this year, it hosted the club-music weirdos of the Mexican record label N.A.A.F.I in a residency unlike anything else the crew had played before.

“We had to think deeper about the social implications of what we were doing,” said Alberto Bustamante, the N.A.A.F.I artist and DJ who performs as Mexican Jihad. “We got to use the experience to talk about things like sexism and the club as a safe space. Usually we only get to do that as a side discussion. But there, we were playing for people with children who would never have showed up at night.”

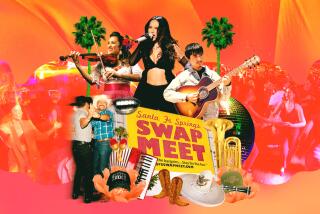

For N.A.A.F.I, it was a career-changing gig, one emblematic of its growing international audience — and the new question of what to do with it. Founded in 2010 by Tomas Davo (who performs as Fausto Bahia) with friends Bustamante, Lauro Robles and Paul Marmota, the crew will make its proper L.A. headlining debut on Saturday at La Transicion, a Red Bull Music Academy Radio mini-festival at downtown L.A.’s Pollution: Studios.

As N.A.A.F.I has grown from a misfit warehouse-party crew into perhaps the most visible group in Mexico’s underground-club-music scene, it has become a flash point for the city’s changing image abroad. Its members represent Mexico City’s growing cosmopolitan status, a role they embrace and resist in equal measure.

“There’s a crowd abroad that’s willing to open themselves to this music,” Davo said. But at the same time, he added, “Mexicans are really aware of their political situation,” and its centuries of resisting colonialism while absorbing outside influence.

While cities such as Berlin (or downtown L.A.) can change in the wake of a club-music renaissance, N.A.A.F.I takes a certain pride in how Mexico City remains a tough place for foreign dilettantes.

“Mexicans are very welcoming, but it’s a hard city to live in,” Bustamante said. “It’s getting comparisons to Brooklyn and Berlin, but it’s a huge city and not at that gentrification-impact yet. If you just come for the cheap rent, the city will chew you up and spit you out.”

They also sneer at the U.S. dance-music promoters who have lately taken to Mexico’s beaches — particularly the hippie-friendly enclaves around Tulum — to throw EDM festivals aimed at moneyed tourists.

“Tulum is a fantasy for Americans,” Davo said. “To Mexicans, [those festivals] all seem elitist. It’s a whole other economy just meant for white people.”

The sound of N.A.A.F.I (an acronym for a charmingly profane statement of commercial disinterest) is similarly defiant and hard to pin down. While the collective’s tracks hit hard in after-hours spaces, N.A.A.F.I has also embraced outre local Mexican styles such as Tribal (low-budget, fast-paced electropop) and a panopoly of Latin and western electronic genres, refracted through a modern Mexican lens.

That sensibility made N.A.A.F.I allies with other genre-busting electronic scenes such as L.A.’s Fade to Mind label, with which N.A.A.F.I threw a 2014 New Year’s Eve festival in Puerto Escondido that helped cement the label’s global reputation. While the artists have earned an international following online, they remain resolutely analog in person, preferring hand-painted murals and other extremely localized ways of getting word out for shows.

For Nacho Nava, the founder of the gay-centric, Latin-leaning Mustache Mondays party at the Lash in downtown L.A. (who consulted and collaborated on the Transicion showcase), L.A.’s current underground scene shares a scrappy sensibility, with which N.A.A.F.I will fit right in.

“I think the kids here really connect with N.A.A.F.I because of their punk mentality,” Nava said. “I live and work out of Boyle Heights and it’s interesting to see this new generation of ‘club kids’ and just how punk and DIY they are. Mexico City and Los Angeles nightlife share a lot of these same qualities. [It’s] just what we need.”

Of course, it’s no coincidence that commercial interests (like, say, an energy drink company) might look at N.A.A.F.I and see the future. As the crew figures out how to grow internationally, it will have to balance that new attention with everything that makes it fundamentally punk.

That includes resisting plans to box its sound into too-easy identity politics. N.A.A.F.I has seen some U.S. promoters send pitches that were overtly “pandering, where they want to make it all about being Latino and brown,” Bustamante said. At the same time, N.A.A.F.I has a testy relationship with the idea of “malinchismo,” or the sense that cosmopolitan Mexicans can sometimes look down on local culture.

For its members, N.A.A.F.I’s not just about representing Mexico. It’s about absorbing the rest of the world as well.

“The community around N.A.A.F.I takes it really personally. They’re proud that we’ve gotten this attention, but there is a side that does worry that maybe we’ll sell out,” he said. “We do want to reach out to the mainstream, or produce for pop artists.”

Bustamante laughed, confident in the sanctity of the project. “But Mexico City is extremely woke.”

Twitter: @AugustBrown

ALSO

Beyoncé’s ‘Lemonade’ up for four Emmys

Ain’t no mountain high enough: 5 times Diana Ross was a total boss

Alicia Keys, Beyonce and more on 23 everyday actions that got black people killed in America

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.