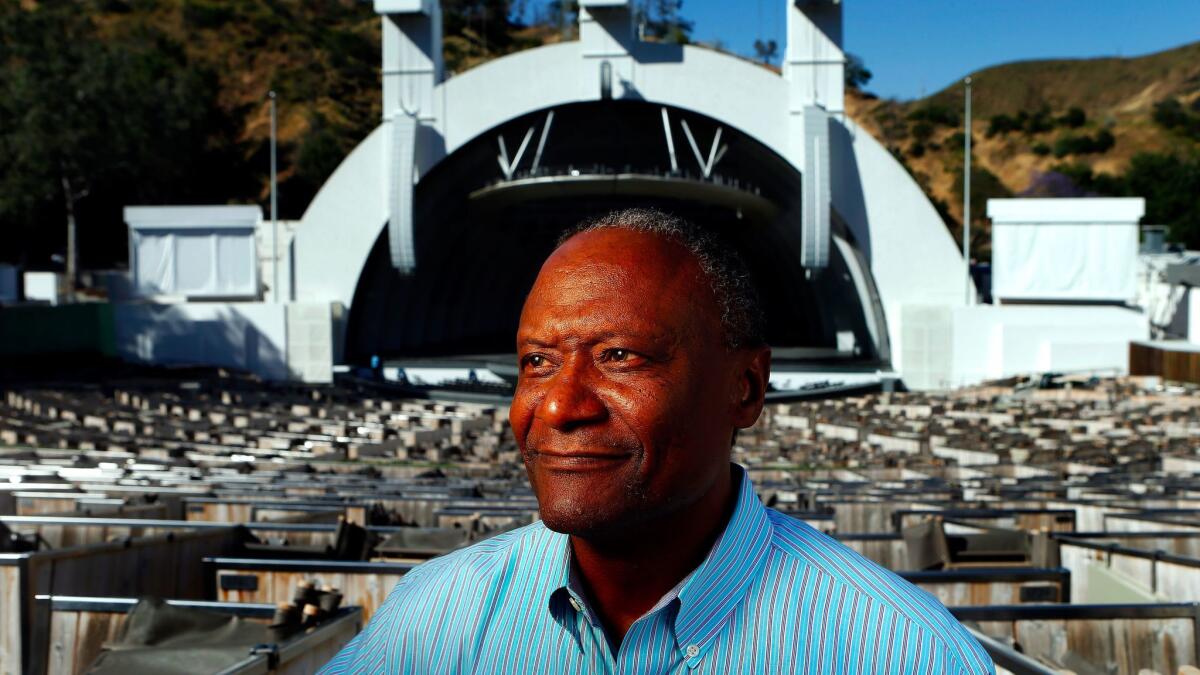

A professor and a comedian: Maestro Thomas Wilkins on why funny works at the Hollywood Bowl

Thomas Wilkins was clearly psyched to learn something new about his iPhone.

“There’s a do-not-disturb function?” the conductor asked when I sat down with him (and set up my phone to record our conversation) on a recent afternoon at the Hollywood Bowl. “Hot dang! You’ll have to show me where that is.”

You can’t blame him for occasionally wanting a little peace and quiet: In addition to his seasonal gig leading the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, which since 2008 has put him on the podium behind the likes of Stevie Wonder, Steely Dan and “Weird Al” Yankovic, Wilkins, 60, serves as the music director of the Omaha Symphony and holds an endowed chair with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Yet it’s precisely Wilkins’ focus — the sense he’d rather be nowhere else — that makes him a pleasure to encounter every summer at the Bowl. Flexing a performance style that’s equal parts maestro and master of ceremonies, he tells thoughtful stories about the music he’s conducting and jokes around with headliners in a way that breaks down the wall between pop act and classical orchestra.

Ahead of Saturday’s opening night concert featuring the Moody Blues, Wilkins discussed working with kids, working with control freaks — and whom he wants to work with more than anybody else.

You perform in venues all over the world. What distinguishes the Hollywood Bowl?

I love the fact that from one night to the next — or even in a given program — the music may not be the same. I’m a firm believer in no-labels music, and the Bowl is just like a giant version of how I live my life. We opened a couple of years ago with the Sacrificial Dance from “The Rite of Spring,” then we had John Legend and Stevie Wonder on. And the first thing Stevie said to me backstage was, “Man, that Stravinsky was rocking!”

Part of what makes those leaps work is the way you contextualize the music for the audience. How did you develop that approach?

I used to do the children’s sermons at my church — I had to learn how to take grown-up ideas and find the words that children could understand. Then it turns out that when I get my first professional orchestra job, one of my main responsibilities is to do young people’s concerts.

Do folks in your field want that job, or do they dread it?

When Boston came along later and asked if I’d be interested in doing it again, I thought, “I don’t want to get known as the guy who does kiddie concerts for a living.” But this was like eight years ago. My manager said, “Wait a minute. You have a job at the Hollywood Bowl, which is kind of pops. You have a music directorship in Omaha, which is classical. The only label people are going to put on you is versatility.” There are some nights when I’m a professor, and there are other nights when I’m a comedian. It really depends on what I think needs to happen at that moment.

You pull from your own life too. I’ve seen you talk about your daughters.

I think we conductors have always been afraid that people weren’t going to take us seriously if we were funny. In the classical music world, for example, because we operate in this primarily Western European tradition, we always thought it was great in America if our leadership had an accent — a European accent.

Because it’s thought to be more refined.

I had a friend who was British — we were both coming up together as conductors — and I said, “Dude, all you have to do is stand in front of an orchestra and say the word ‘perhaps,’ and you sound brilliant.” But guess what? We don’t have any authority that this music didn’t give us. So when you present yourself as a person who is privileged to be a part of something that’s so much bigger than we are, then the audience will receive anything.

Does your role change when the orchestra is playing with a pop artist? Now you’ve got more personalities in the mix — maybe there’s less space for you to do your thing.

Look, I serve at the pleasure of the guest. Nobody’s coming because it’s Tom Wilkins’ name on the marquee.

What about the musical direction of the show? I was surprised when Steely Dan agreed to play with the orchestra last year, given the band’s famous grip on their sound.

I flew to Chicago to meet Steely Dan before they got here. All of a sudden we’re adding 70 bodies to something they’re trying to control; I went to say, “It’s going to be OK — my guys aren’t afraid of the word ‘groove.’” One of the best parts of working at the Hollywood Bowl is we choose our own arrangers for the most part. So that mitigates a lot of that stuff. But there are times when it doesn’t work. The B-52’s did not want to play with the orchestra [in 2015]. They were afraid of their lack of control, or that it would put them in a box, whatever. Our guys talked them into three charts, I think, and then they got here and went, “Holy cow, this was a mistake! We should have had all our songs done.”

Do artists ever show up without much interest in what the orchestra’s going to do?

I don’t remember his name, fortunately, but I can recall one act we had where it was as if the orchestra wasn’t even onstage. I stayed pissed off all night long. It didn’t make any sense. Why are you even here if you’re not going to acknowledge the fact that these men and women are back here making your music sound better?

Who are you burning to play with that you haven’t gotten to yet?

James Taylor. He’s my all-time favorite artist in any genre.

What do you love about him?

I love the quality of his voice. I love his poetry. “Me and my flea, we were down by the water / Fell in a hole with Superman’s daughter.” Who thinks to say that? There’s a moment in a song called “Another Day” where he’s singing in his head, and just as he gets to the bottom of the line he’s in his chest — it’s one of my favorite moments in all of music. I also put the slow portion of the last movement of Mahler 1 in that category, by the way.

I feel like James Taylor with an orchestra is an attainable goal.

I feel like it is too, man! I’ve almost had the chance to work with him twice. He’s a big fan of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, so those guys are on high alert.

Or, you know, you could do it here.

Hmm. That’s not a bad idea.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

ALSO

The Beatles’ best album is really its worst. ‘Sgt. Pepper,’ we need to talk

What Chuck Berry's and Glen Campbell's final albums have to say about the end of the road

Steely Dan with strings at the Hollywood Bowl? 'For some reason we decided we were gonna do this'

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.