Walter Becker, co-founder of Steely Dan, dies at 67

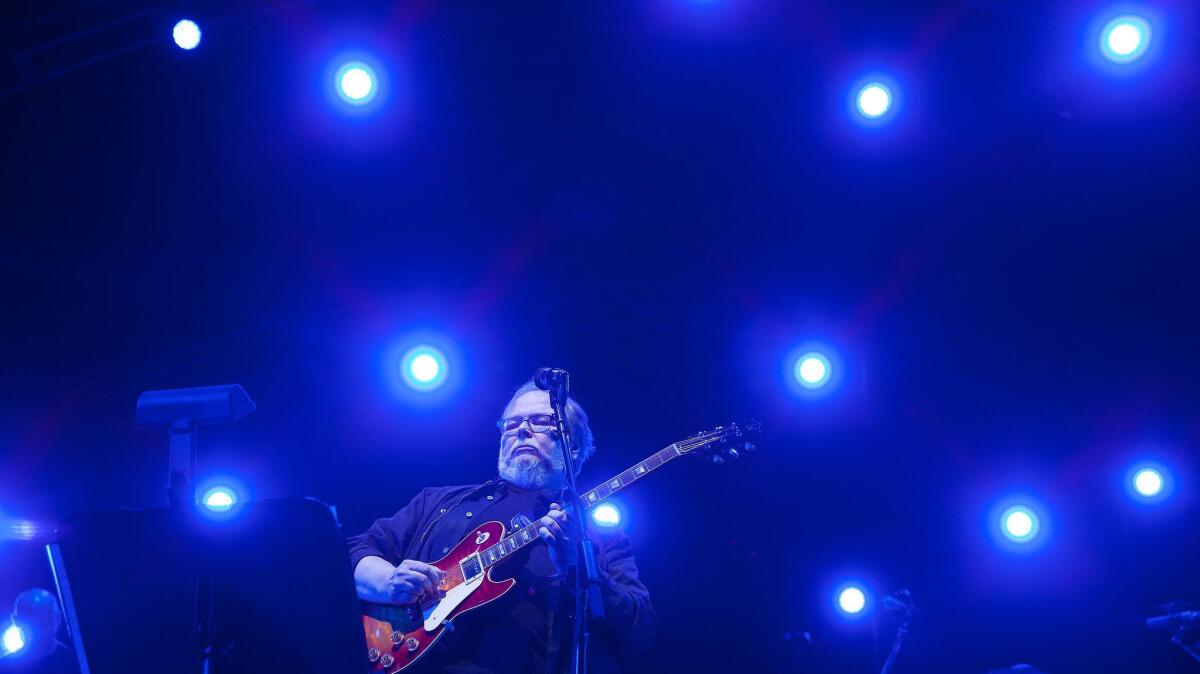

Walter Becker, the co-founder of Steely Dan who was known for his acerbic wit and his proficient work with the guitar, has died. He was 67.

As one of the key architects of Steely Dan, Becker and longtime musical partner Donald Fagen were responsible for numerous hit songs and albums throughout the band’s 1970s heyday. Often low-key and influenced by jazz or R&B, Steely Dan’s patiently calm arrangements contrasted with the band’s dark sense of humor and heavily poetic lyrics — word puzzles that were often caked in cynicism and subtle perversity.

No cause of death was given, and Becker’s death was first announced by the artist’s official website early Sunday. Shortly after, Fagen released a statement through a publicist in which he pledged to keep Steely Dan’s music alive and praised his collaborator as “smart as a whip, an excellent guitarist and a great songwriter.”

“He was cynical about human nature, including his own, and hysterically funny,” Fagen wrote. “Like a lot of kids from fractured families, he had the knack of creative mimicry, reading people’s hidden psychology and transforming what he saw into bubbly, incisive art.”

Becker had recently missed the band’s July performances in Los Angeles and New York as part of the Classic West and Classic East festivals. “He took ill shortly before he was to come to California,” Fagen said on stage at Dodger Stadium on July 15. “We wish him a speedy recovery.”

Steely Dan, named after a William Burroughs term for a marital aid in his book “Naked Lunch,” formed in the early ’70s, years after Becker and Fagen met at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y. The act was known for heady songs full of unexpected sonic detours, and the band’s ornately and painstakingly produced albums, such as 1974’s “Pretzel Logic” and 1977’s “Aja,” are today considered signature works of the decade.

“Pretzel Logic” became the band’s first album to reach the top 10 in the U.S., its success fueled heavily by the single “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” a tune that documents an overly confident, arguably delusional and likely ill-advised romantic pursuit. The song broadcast Steely Dan’s love of jazz, as it pulled its riff from pianist Horace Silver’s light-stepping, Brazilian-tinged staple “Song for My Father.”

Becker and Fagen were essentially the only constants of Steely Dan, which by the mid-’70s had ceased touring and increasingly relied upon a revolving cast of ace musicians. For 1975’s “Katy Lied,” for instance, the act underwent significant lineup shifts and the work was the first to highlight Michael McDonald, who would later go on to fame with the Doobie Brothers, as a vocalist on a Steely Dan album.

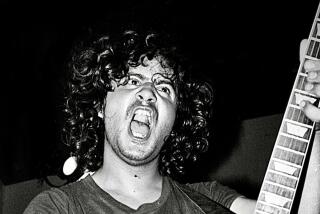

Becker and Fagen were often a study in contrasts themselves. Fagen, wrote former Times music writer Richard Cromelin, “always seemed the more human half of Steely Dan — his sarcasm was downright benign next to Walter Becker, a baby-faced sadist who delighted in turning interviewers into whimpering wrecks.”

The Steely Dan creation myth often notes that Becker and Fagen were drawn to each other via a mutual disdain of hippie culture as well as an adoration for jazz, comedy, science fiction and writers such as Vladimir Nabokov and Kurt Vonnegut. In the late ’60s, the two worked with pop act Jay and the Americans before heading to Los Angeles to work as songwriters and eventually embarking on a career with themselves at the forefront as Steely Dan.

Early on, Becker largely played bass, and he said he was encouraged to focus on the guitar by Fagen. In time, he developed a languid and loose style that could seamlessly drift among jazz, blues and rock — a proficient and reassuring sound that tempered his off-stage or between song satirical incisiveness.

“Donald wanted me to play guitar because he felt that we’d end up with something weirder and more interesting if I did it,” Becker told The Times in 1994. “A lot of times, we’d get somebody to come in and try something and we’d listen to it, and it would be too ordinary or [the guitarist] wouldn’t understand it in any unusual tonal way. That was the problem we had a lot of time back then.”

The band drifted after the release of 1980’s “Gaucho,” regularly citing fatigue, personal disagreements and drug abuse, but reunited in 1993. In 2000, the act released its first studio album in two decades with “Two Against Nature.” The album would eventually win the Grammy Award for album of the year and help Steely Dan remain a touring force well into its fifth decade.

Becker was born Feb. 20, 1950, in Queens, N.Y., and in the early ’80s he retreated to Hawaii to focus on living a cleaner lifestyle. During Steely Dan’s hiatus, Becker stayed out of the spotlight, occasionally working as a producer for such artists as Rickie Lee Jones and China Crisis, but not releasing his debut solo album until 1994 with “11 Tracks of Whack.”

Though it leaned, albeit slightly, a little more rock ’n’ roll than some of Steely Dan’s material, it showed Becker hadn’t lost any of his edge.

“I came up with that title when I realized that a lot of the songs I wrote were not motivated by my love of my fellow man,” he once told The Times. “As much as anything else, they rank on people or are lashing out or, in some cases, are about people who are dead.”

Yet Becker and Fagen proved far more potent together than separate, and after returning as a touring entity in 1993, Steely Dan slowly returned to active recording duty. In 2003, the band released its second album since reuniting, “Everything Must Go,” and in 2015 Steely Dan represented the classic rock set at the youth-focused Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival.

Shortly after that appearance, Becker spoke to The Times about the balance of staying artistically challenged while recognizing the audience’s penchant for nostalgia.

“I don’t think we deny it,” he said of respecting the crowd’s desire to reminisce. “We don’t go out of our way to make a big deal out of it or to put it at the forefront of what’s happening. But it’s there; it can’t not be there.

“And to the extent that it is there, I think it’s satisfying for the audience — and it’s satisfying for us too. It’s satisfying to make the connection with people, especially given that we may not be the most socially affiliative people in the world.”

There was no information immediately available on Becker’s survivors.

Twitter: @Toddmartens

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.