Lankershim Boulevard rides to prominence in the Valley

- Share via

The momentum that has built up along much of Lankershim, especially in the North Hollywood Arts District, illustrates what can arise from a mass-transit network.

Click the blue mile markers above — or use the arrows — to take Christopher Hawthorne's guided tour of key sites along Lankershim Boulevard.

Dec., 22 2012

Twenty years ago, nobody would have included Lankershim Boulevard on a list of the most significant streets in the San Fernando Valley.

Passing the front gates of Universal Studios was pretty much its high point; beyond that, as it ran north for seven miles toward Sun Valley and Interstate 5, Lankershim was a grim parade of gas stations, windowless storage warehouses and rundown motels.

Today, the boulevard is emphatically on the rise, energized by a pair of Red Line subway stops, a rapid-bus route packed with riders and the flourishing North Hollywood Arts District. As Van Nuys Boulevard and other car-dominated routes endure a slow fade from their post-war prominence, the stretch of Lankershim between the Red Line stations now ranks as the most vital north-south corridor in the Valley.

Commuters stream through North Hollywood's Metro Red Line Station, the creation of which helped the arts district take off in a big way. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Its ascent makes clear that the hierarchy of Southern California boulevards is being reshuffled by the growth of the region's bus and rail network.

But there are obstacles in Lankershim's way, some of which suggest that Los Angeles is struggling to integrate new mass-transit lines into the life of the city — and still turning almost reflexively to outdated planning strategies that bow to the automobile.

Changing direction

In the L.A. Basin, boulevards tend to grow wealthier and more manicured as they move north. On the other side of the Santa Monica Mountains, in the San Fernando Valley, the opposite is true.

The hills are the city's equator, flipping the geographic relationships upside down. In the Valley, privilege is concentrated along the southern end of nearly every north-south boulevard.

That's certainly the case on Lankershim, named for the German immigrant Isaac Lankershim, who bought 60,000 acres of ranch land, essentially the southern half of what would become the San Fernando Valley, in 1869. The seller was Pio Pico, the last governor of Mexican-ruled California.

Today the boulevard's southern end is stuffed with history and signs of wealth. Directly across from Universal Studios but unknown to many Angelenos is the fenced-off site of the Campo de Cahuenga ranch house, unearthed during excavations for the Red Line in the 1990s. A treaty signed there in 1847 paved the way for the end of Mexican rule in California and the dawn of Anglo Los Angeles.

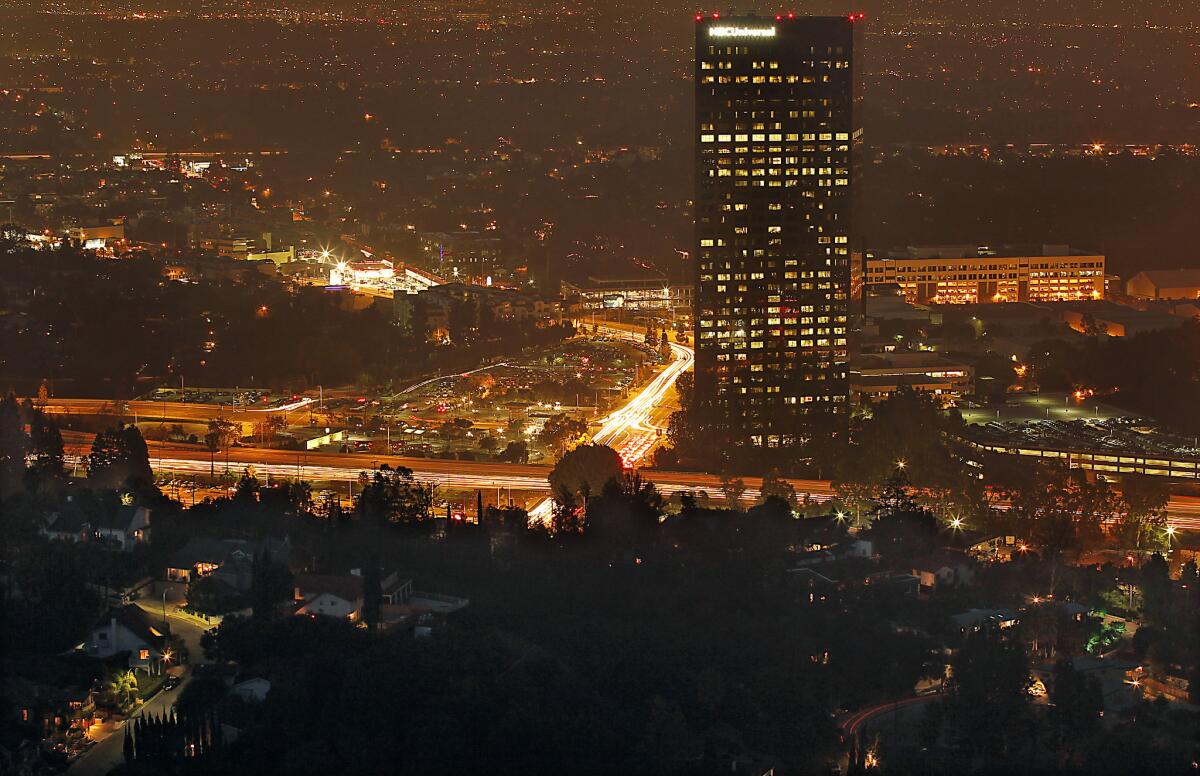

It's a half-hearted monument, to be sure, open just one day a month. Looming over it from the other side of the boulevard is a more conspicuous and more modern landmark: 10 Universal City Plaza, designed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill and finished in 1984. At 36 stories it is not only the tallest building in the Valley but among the more underrated skyscrapers in Los Angeles.

At the southern end of Lankershim stands Campo de Cahuenga, a rather half-hearted tribute to L.A.'s Mexican past that's open just once a month to the public. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Lankershim passes the Los Angeles River at one of the river's widest points before arriving at the St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church, where Bob Hope's funeral was held in a sunrise ceremony in summer 2003. Built in 1959 at the height of modern architecture's influence in Los Angeles and around the country, the church was designed by J. Earl Trudeau not simply to suggest the Spanish Colonial Revival; with its chunky, oversized ornament, it looks almost cartoonishly pre-modern.

A mile past the church lies the North Hollywood Arts District, an encouraging case study in the effect that new transit lines can have on a neighborhood. In the 1990s, the Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency, or CRA, began investing heavily in North Hollywood, financing real-estate development and subsidizing renovations by a number of theater companies along Lankershim.

With the 2000 extension of the Red Line into the Valley, with stops at Universal City and in North Hollywood, those investments began to pay off. A CRA-aided project called the NoHo Commons, begun in 2003, brought new shops and apartments within a few feet of the Red Line.

In 2005, the opening of the Orange Line rapid-bus route, running east-west across the Valley from Warner Center to the corner of Chandler and Lankershim, provided another boost. It carved out a 14-mile-long dedicated right of way, part of which once moved Southern Pacific trains and Red Car electric trolleys, for extra-long Metro Liner buses.

Extended over the summer north to Chatsworth, the Orange Line now carries 30,000 passengers on an average weekday, significantly outpacing early projections. Much cheaper to build than rail, the rapid-bus route is the clearest success story in the great Metro expansion of the last two decades.

Today the sidewalks in front of the new Laemmle movie house just south of the Orange Line-Red Line junction are often crowded. In the evenings so is the Federal Bar in a restored brick building across the boulevard. Actors mumbling their lines hurry to auditions as groups of martial-arts students spill out of karate and tae kwon do studios.

The underrated 10 Universal City Plaza, the tallest building in the Valley at 36 stories, looms over Lankershim Boulevard. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

"We've seen this little stretch of Lankershim really blossom," said Bill Brochtrup, co-artistic director of the Antaeus theater company, which moved into a 49-seat space in North Hollywood in 2007. "It's becoming a walking destination and a pedestrian zone. Five years ago I didn't see that as much. It was a little dicey."

Now that the Red Line runs until 2 a.m. on weekends and the Orange Line even later, Brochtrup added, theater and improv companies and comedy clubs can try out later curtain times. "Like Melrose, downtown, these other hipper neighborhoods, we can do these late-night events."

"I almost can't believe I'm saying that about Lankershim," he said. "But we're proud Valleyites now."

The recession and the recent demise of the state's redevelopment agencies have slowed some of the arts district's momentum. Development plans by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which owns 15 acres at Lankershim and Chandler, may give it fresh energy. Already the transit agency is moving forward with a plan to restore the 1896 Southern Pacific rail depot at the intersection, a low-slung building that is one of the oldest surviving structures in the Valley.

A trickier question is how to revive the unsettled northern stretches of the boulevard, where the foot traffic generated by the Red and Orange lines thins out and prostitutes pace the sidewalks before the sun goes down.

A dozen medical marijuana dispensaries have popped up on this part of Lankershim, slipping into low-rent storefronts and forgotten strip-mall corners. With their telltale green crosses and green-painted facades, the pot shops are a hardy, opportunistic strain that neighborhood groups have found almost impossible to stamp out.

At the same time, the dispensaries offer a clear if unorthodox lesson for cities interested in changing their boulevards quickly and cheaply.

The pot shops that dot the northern half of Lankershim have added their own bit of branding to the landscape, with bold graphics, green signage and those telltale crosses. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

It has taken the NoHo Arts District two decades and many millions of dollars to remake itself. The stretch of Lankershim two miles north has meanwhile reinvented itself, for better or worse, in a much shorter span, with the dispensaries creating a recognizable collective brand on the strength of some green paint and muscular graphic design.

Against the grain

Lankershim's lower half slices across the Valley at much the same angle that Broadway moves across Manhattan, from northwest to southeast. That sense of cutting against the grain has given Lankershim a personality distinct from the Valley's other north-south boulevards.

The growing popularity of the Red and Orange lines has thrown that difference into high relief. As nearby boulevards hold fast to their suburban, car-friendly roots — and to the sense of separation from the rest of L.A. that has always been at the heart of the Valley's appeal — Lankershim is reaching back even further, reconnecting with its century-old history as a transit crossroads.

L.A.'s transportation bureaucracies, however, seem determined to tamp down some of its emerging street life. Metro plans to build both a $22-million pedestrian tunnel to connect the Red and Orange lines in North Hollywood and a $20-million footbridge over Lankershim at the Universal City subway stop.

The strategy seems sensible enough on its face, aiming to protect pedestrians from racing car traffic and close gaps between Metro stations — and between those stations and the boulevard — that should never have existed in the first place.

The bridge to Universal Studios is the long-delayed product of a 1994 agreement between Metro and Universal's parent company at the time, MCA. Bob Hale, a partner in Rios Clementi Hale Studios, which is designing the bridge, said the existing crosswalk was simply insufficient to accommodate the estimated 2 million visitors who arrive at Universal Studios by subway every year.

"You have strollers, people not knowing where they're going," Hale said. "The first time a little kid or a family gets run over by an impatient driver, we're all going to look stupid if we don't address this."

The stretch of Lankershim Boulevard in North Hollywood that includes the Metro station and various theater companies and clubs has blossomed over the years. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

In North Hollywood, meanwhile, surging ridership on the Orange Line means that crowds of passengers transferring to the subway overwhelm Lankershim's crosswalks several times per hour. According to Metro figures, more than 70% of Orange Line riders getting off at Lankershim head directly for the Red Line.

But the safety issue turns out to be a straw man — and a particularly flimsy one at that. Recent studies have made clear that the more kinds of users crowd together along a boulevard, the more cautious drivers tend to be.

Putting pedestrians and drivers into separate silos of space, as the bridge-and-tunnel plan would do, isn't just a remnant of modernist urban-planning theories that have been widely discredited. It would send drivers a clear message that they're in control of the boulevard, free to drive even faster than they do now.

Simple and far cheaper solutions at both locations — widen the crosswalks, give people more time to get from one side to the other and ticket drivers who fail to yield — would have the benefit of smoothing the pedestrian flow and making the intersections safer at the same time.

Yet that approach has won little support from Metro, for one basic reason: What's driving the proposals to remove pedestrians from the boulevard is not just a concern for their safety. It's also a fear of traffic congestion along Lankershim, a worry that all those people on foot are proving an impediment to the free movement of cars.

In North Hollywood, said Metro's Aspet Davidian, the pedestrians crossing between the Orange and Red lines are increasingly "disrupting to traffic."

About the Universal City stop, Hale said, "What happens in this intersection ripples out across many, many other intersections and even to the freeway."

All types of signs dominate the landscape at the intersection of Lankershim, Ventura and Cahuenga boulevards in Studio City. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Given that Hale's firm is also at work on an ambitious master plan for the NBCUniversal campus, his comments may be predictable. But his eagerness to defend the bridge design is also a sign of a fitful, sometimes contradictory evolution in L.A.'s attitude toward the public realm.

Recent projects by Rios Clementi Hale include the polka-dotted Sunset Triangle Plaza in Silver Lake, Grand Park downtown and an ambitious redesign of the Century City streetscape. Those designs have challenged head-on the primacy of the car in Los Angeles and opened up new space for those on foot.

And in the Valley, along a boulevard that is otherwise showing the dramatic benefits of an expanding transit network for sidewalk activity and economic development? There the firm seems all too happy to mount an old-fashioned defense of car culture, producing in its footbridge design a conspicuous monument to the perceived vulnerability of the L.A. pedestrian.

Explore: Atlantic Boulevard, Crenshaw, Lankershim and Sunset Boulevard with Christopher Hawthorne Los Angeles Times Architecture Critic.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

Graphic credits: Lorena Iniguez Elebee | Graphics reporting: Julie Sheer | Programming: Anthony Pesce | Produced by: Lily Mihalik

Sources: ESRI, TeleAtlas