Tablets: Downloadable classic books are in abundance

Let’s say you’re getting, or giving, a new tablet or an e-reader (iPad, Kobo, Nook or Kindle Fire) for the holidays. Here’s an idea for what to do with it: Load it first with free books. Thanks to Project Gutenberg, as well as the cultural gift known as public domain, you can build a library, as I have, with a variety of classic literature, gratis: Daniel Defoe’s “A Journal of the Plague Year,” Benjamin Franklin’s “Autobiography,” Kate Chopin’s “The Awakening.” It’s enough to make you believe in the free flow of ideas.

OK, OK, I’ll admit it: I’m a sucker for free books. They’re the gift that keeps on giving, a gift the culture gives itself. This makes for an interesting dynamic in a money-driven society such as ours. What is the value of books if they cost nothing? Are they worthless? Or priceless, a gift that literally knows no price?

I’ve wondered about this, on and off, since college, when I scoured used bookstores, bringing home grocery bags full of paperbacks — the building blocks of my own library. Back then, I could buy 30 books for three dollars, which inspired an indiscriminate serendipity.

Among my discoveries? An old hardcover of Thomas Wolfe’s “Of Time and the River”; Terry Southern’s “Flash and Filigree”; the collected works of Warren Miller, a novelist who died at 44 in 1966 and left behind seven books, including the spare and unsentimental urban novel “The Cool World” and “90 Miles From Home,” an impressionistic portrait of Castro’s Cuba, published in 1961. Miller, in particular, is almost entirely forgotten, as he was when I first stumbled across him in the 1980s. Is it too much to suggest here that the value (the gift, as it were) cuts both ways, that I might somehow help preserve him even as he enlarges me?

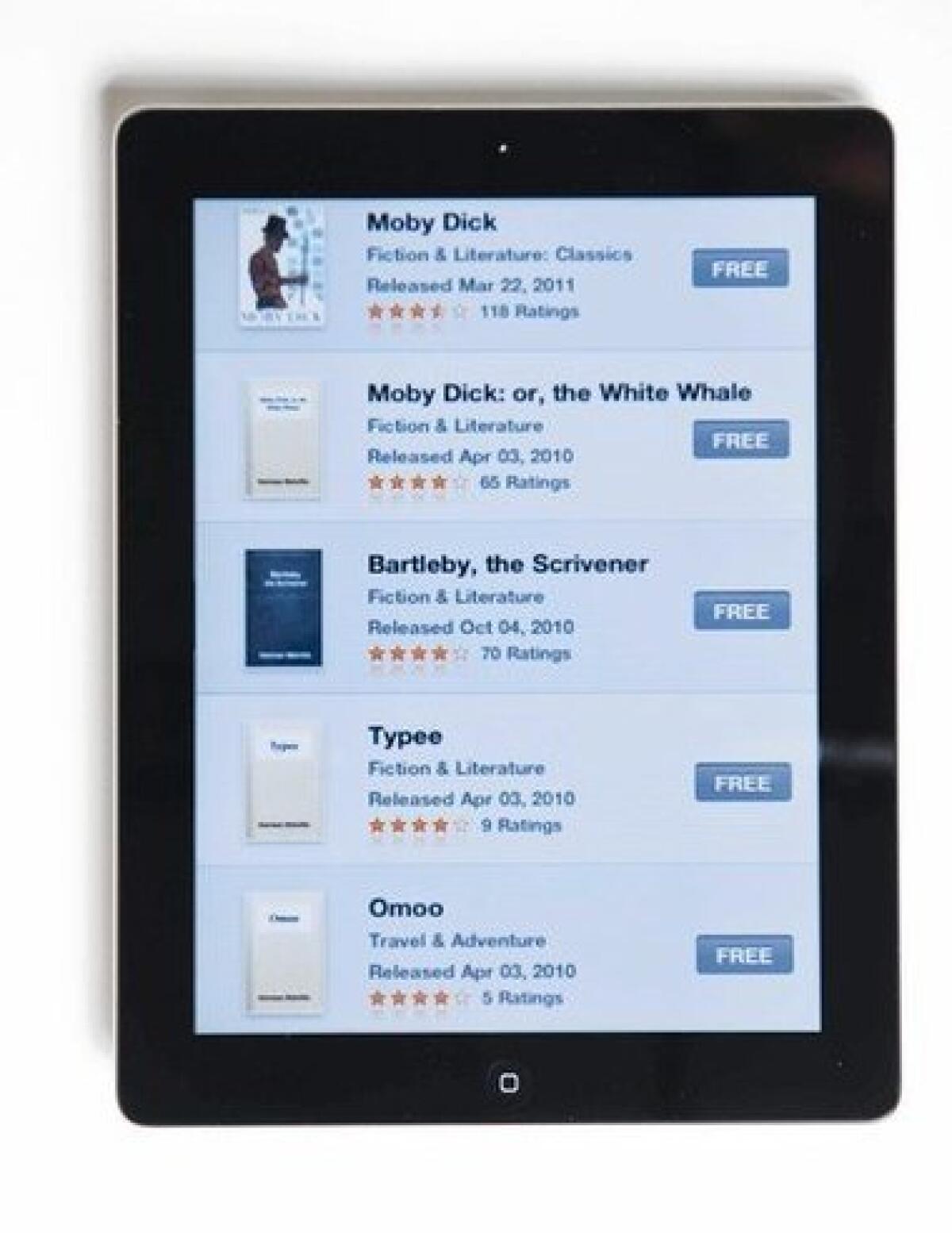

Miller’s books are not available digitally; they’re out of print and still in copyright, a literary limbo of the lost. Hundreds of thousands of other titles are available, however — both by leading figures such as Shakespeare, Dickens and Tolstoy and by those (George Gissing, for instance, or Sherwood Anderson) who could benefit from rediscovery. My iPad holds all that and more: Henry Fielding, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Friedrich Nietzsche staring into the void. It collects “Common Sense” and “The Federalist Papers,” as it’s useful to remember where we came from, if only to see how far we’ve strayed.

In a sense, this is a back-to-the-future situation, using 21st century technology to read 18th and 19th century books. They’re not interactive and they don’t address the current moment, except inasmuch as great writing always addresses the current moment because of its humanity. I’ve been reminded of this in recent weeks as I reread Herman Melville’s 1853 novella “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” with its subtitle “A Story of Wall-street” and its stirring refrain, “I would prefer not to”; the protagonist is a Wall Street law clerk who will only let himself be pushed so far. Is there a more appropriate literary antecedent, 158 years before the fact, for the Occupy Wall Street protests?

Not long ago, at a party, someone recommended Joseph Conrad’s “The Point of Honor,” a satire about two officers who engage (or try to) in a duel. When I got home, I downloaded the book, which I hadn’t known before. It’s not that “The Point of Honor” is obscure, particularly; there are any number of editions, some published under the title of “The Duel.” And yet, for me, that’s the, er, point precisely, the way the boundary between digital and print blurs.

What does it mean that we can read as easily, as fluidly, on the screen as on the page? What does is mean that we can now take them both for granted, that it’s not the form but the content with which we are concerned? What does it mean that the past becomes the future, that we do not lose but, in a way, regain the world? Only this: That, whatever else it offers, technology gives us the gift of returning us to an earlier version of ourselves.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.