Greg Louganis dives into the spotlight with HBO’s ‘Back on Board’

He was perhaps the greatest diver in history but never made the cover of a Wheaties box. He was once one of the biggest names in sports, shaking hands with presidents, hanging out with Brooke Shields, co-writing a No. 1 bestselling memoir, posing nude for Playgirl.

But Greg Louganis says that these days he can’t even get a chance to strut his stuff on “Dancing With the Stars.” Things got so bad a couple of years back, his beloved cliff-side Malibu house was nearly lost to foreclosure (he ended up selling it instead).

The limelight now though seems to be swinging back to the four-time Olympic gold medalist — at least for a little while. The 55-year-old retired diving superstar is the subject of “Back on Board: Greg Louganis,” a documentary (premiering Tuesday at 10 p.m. on HBO) that examines his dizzying spiral to glory in the 1980s as well as his stunning professional and financial setbacks since. The film recounts the homophobia that he and others suspect played a role in stunting his career. With the cameras rolling, he pleads over the phone with a bank representative for mortgage relief that would allow him to keep his house.

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

Louganis doesn’t climb up on the springboard much anymore — he’s more into yoga and circuit training — but as a mentor to young athletes he shares his philosophy of the sport that made him a household name.

“A dive takes less than three seconds,” he said during a recent interview at his apartment in Beverly Hills, which he shares with his husband of two years, Johnny Chaillot, who works as a paralegal at a nearby Century City law firm.

“I tell the kids all the time, ‘Winning an Olympic gold medal, it’s not about perfection. You don’t have to be perfect. It’s usually the one who makes the least amounts of mistakes or the least visible mistakes [who wins]. It’s all about how successful you can be at that moment in time, in that three seconds.’”

Life lasts a lot longer, of course, and the rules can be a little different. But fame? That, Louganis discovered, can be nearly as fleeting as a back dive into a pool. And fame frequently takes, like a dive, a path straight down.

When “Back on Board” director Cheryl Furjanic approached Louganis about a biographical movie several years ago, she dangled the idea of rescuing his name from obscurity and presenting him as a pioneering openly gay athlete.

“She taught documentary filmmaking at NYU,” Louganis recalled. “She took a rather informal poll and found that kids under the age of 27 didn’t know who Greg Louganis was. She said, ‘I really want to change that because you’ve had such a tremendous impact on LGBT [issues], human rights, HIV education awareness, that people really should know that history. ... Are you game to change that?’ I said, ‘Sure, why not?’”

Louganis’ past and present proved much more complicated, however, than even the filmmakers realized when they started the project.

Price of success

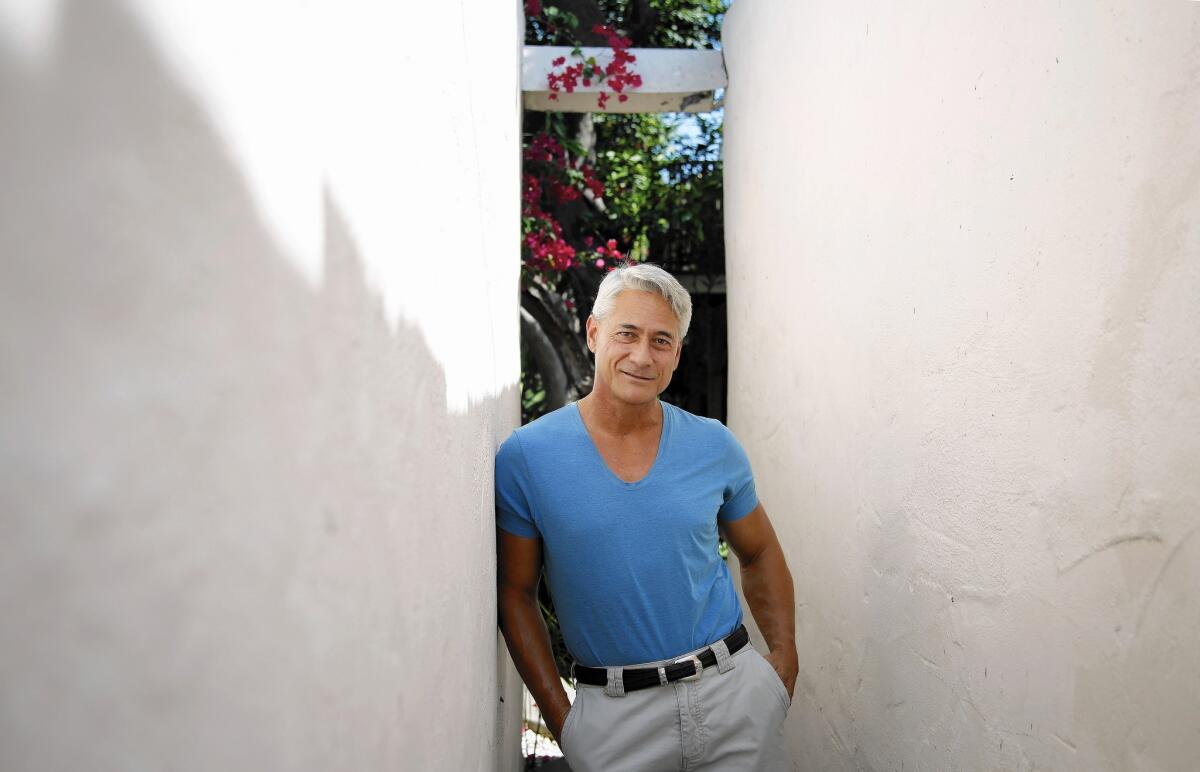

Louganis is still strikingly handsome, even boyish-looking, although his once-black hair grayed long ago and his tanned face is crossed with laugh lines. His 5-foot-9 frame (“two inches too tall” for ideal divers’ form, he recalled with a laugh) remains taut and muscular, with biceps the size of melons. Even well into middle age, he represents an impossible-to-attain physical ideal.

This was the form that captured the imagination of the world starting in 1984, when he won two gold medals at the Los Angeles Olympics for 3-meter springboard and 10-meter platform diving.

Sports experts say that he likely would have swept gold in 1980 as well had the U.S. not boycotted the Olympics because of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. He won his first world championship when he was just 18.

So dominant were his achievements that for many Americans, Louganis wasn’t just great at diving, he was diving. Nearly everyone knew his name; few could name even one of his competitors.

“Often the only question was not whether he was going to win, but rather whether he’d set a record or whether he’d already have the competition secured before his final dive,” said Andrew Billings, a sports media expert and professor at the University of Alabama who is researching a book on openly gay athletes.

“His name has become like a verb for ‘taking a dive,’” said Will Sweeney, the producer of “Back on Board.”

Success came early but not without cost. Born in El Cajon, Louganis was given up for adoption by teenage parents. His adoptive parents, Frances and Peter Louganis, splurged on plenty of dance and gymnastics classes for Greg, who was showing impressive athletic gifts by the time he was 3. But the boy soon locked horns with Peter, an Air Force veteran who according to Louganis could resort to physical abuse to achieve goals.

“He’d whip me until I’d do the dive that I was afraid to do,” Louganis said. “When I asked him about that [years later], he said, ‘Well, I saw this all this potential and I didn’t want you to throw it away.’ That was the only way that he felt he could get it out of me.” According to Louganis, the pair did not mend fences until Peter was dying of cancer and his Olympian son set aside time to help with his care.

Louganis found a surrogate dad of sorts in Ron O’Brien, the diving coach who helped guide him to world championships and Olympic triumph. In “Back on Board,” Louganis is filmed sitting with the now-elderly O’Brien and presenting him with one of his gold medals from the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Those were the games when Louganis had, in a rare technical error, slammed the back of his head on the springboard during the preliminary dives. He ended up winning anyway — and cementing his status as an international celebrity.

“I’m a firm believer you don’t achieve greatness on your own,” Louganis said. “It was my coach, Ron O’Brien … the training and the trust and the teamwork. We made a great team for 20 years.”

There was also a dark side to the diving team. In one particularly painful scene from “Back on Board,” Louganis talks with former diving teammates about a homophobic locker-room bullying campaign in the years leading to the Olympics. He wrote about being gay and HIV-positive in his bestselling 1995 memoir “Breaking the Surface,” becoming one of the first major athletes to come out.

“Kids today don’t know” about that history, he said. “They wanted to quarantine people living with HIV. They wanted to tattoo us. It was crazy. There was a lot of fear.”

A surprising boost

Sweeney and Furjanic, the producer and director of “Back on Board,” pieced together financing for the film from a Kickstarter campaign, nonprofit support and individual contributions. One major cost consisted of paying for rights to use the voluminous video footage of Louganis’ Olympic feats.

But then help came from a most unlikely source. After a screening at Outfest, an organization devoted to gay-themed films, Sweeney said he was approached by a familiar-looking man whose identity he could not quite place. The man said he wanted to have a screening at his house and invite his TV industry friends so that the film could get more exposure.

That stranger turned out to be Marc Cherry, the creator of “Desperate Housewives,” who is known neither for his professional interest in diving nor for nurturing documentaries. But Cherry was as good as his word. He set up a private showing for the movie; one of the attendees, Howard Rosenman, producer of such fare as “Father of the Bride,” in turn recommended “Back on Board” to HBO programming chief Michael Lombardo.

Sweeney believes homophobia played a role in curbing Louganis’ ability to profit from his stardom.

“There’s a direct causal relationship between his being open about his sexuality with his teammates and with the diving world, and his inability to get those marquee endorsements,” Sweeney said. “One of the moments that’s sort of striking in this film: He’s standing at the International Swimming Hall of Fame and they have an entire row of Wheaties boxes from divers and swimmers you’ve never heard of.”

Billings, the University of Alabama professor, agreed. “Clearly his being a gay athlete was a hindrance for his marketability,” Billings said. “Society has progressed for many of our modern openly gay athletes, yet the stories of people like Louganis are still too hidden.”

Louganis himself is philosophical about whether “Back on Board” will help change that.

He’s run diving camps and also helped mentor athletes at the 2012 Olympics; as it happened, he was in London when his Malibu house was nearly sold in a foreclosure auction. (He says he got behind in payments because of a botched rehab job from a contractor who claimed his house had mold.)

But he’s looked askance at a career in coaching. “Just because you can do something and do it well doesn’t necessarily mean you can teach it,” he said. Working in some sort of administrative capacity holds little appeal, either: “I have to question the motivation of a lot of people in power,” he said, adding that he has been turned off over the years by what he sees as conflicts of interest between Olympic officials and corporate sponsors.

He did find some work as a judge on the reality diving series “Splash,” which he says helped pay a lot of bills. But he would love to do “Dancing With the Stars,” which would seem a natural fit with his Olympic background and love of dance. But he says producers have rebuffed repeated appeals.

“Initially their response was that I had too much dance training,” he said. “As things evolved, there was — I don’t know, I didn’t fit the right profile. There were just all kinds of reasons.” ABC had no comment, but a source close to the show says Louganis was deemed not the right fit during previous seasons but is not out of the running in the future.

Louganis says he’s not the only athlete to suffer from a condition he calls “the post-Olympic blues.”

“A lot of Olympians, they don’t talk about that, about how after your Olympics are over and that if you’re successful, you have this high-high, but then you have this low-low,” he said. “Because it’s the question of, ‘Now what? Who am I? What worth do I have?’

“Then you don’t have your sport. And you thought you’d have your sport forever.”

ALSO:

Review: ‘Wet Hot American Summer,’ the series, on Netflix

TV Picks: ‘UnReal,’ ‘Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll,’ ‘Treehouse Masters’

Trevor Noah: Jon Stewart’s a white ‘Jewish guy’ from New Jersey; ‘I’m not’

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.