Review: PBS’ ‘Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth’ honors a singular life

- Share via

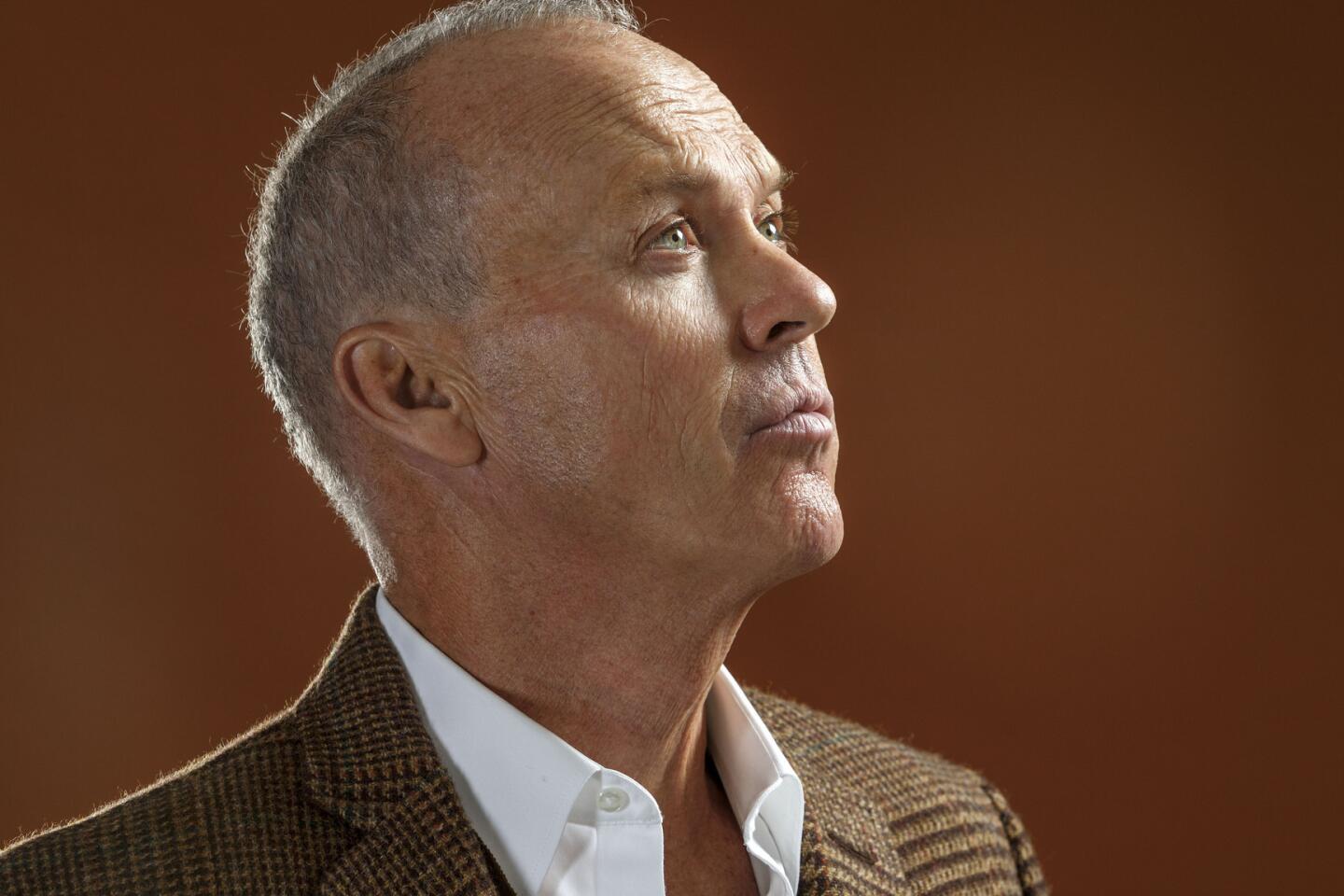

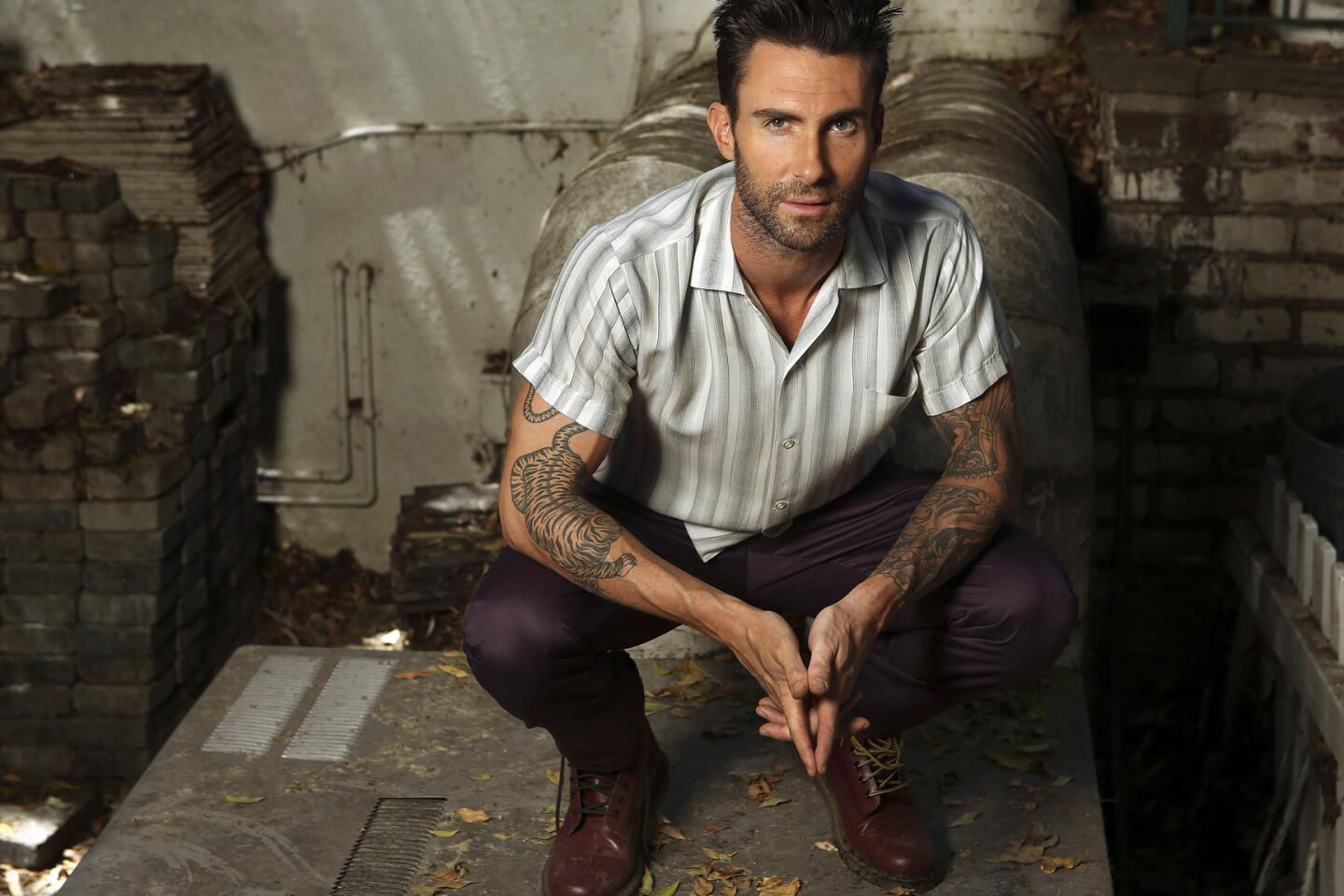

As the title of this episode of “American Masters” suggests, “Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth” is a lovely and lyrical tribute to the great American writer and activist who turns 70 on Sunday, two days after the film airs on PBS.

February is, of course, Black History Month, which makes the non-birthday aspect of the timing dispiriting. Surely it shouldn’t require an African American-themed event to warrant a tribute to Walker. And yet it is also reaffirming as well since it looks like Black History Month remains a very good idea.

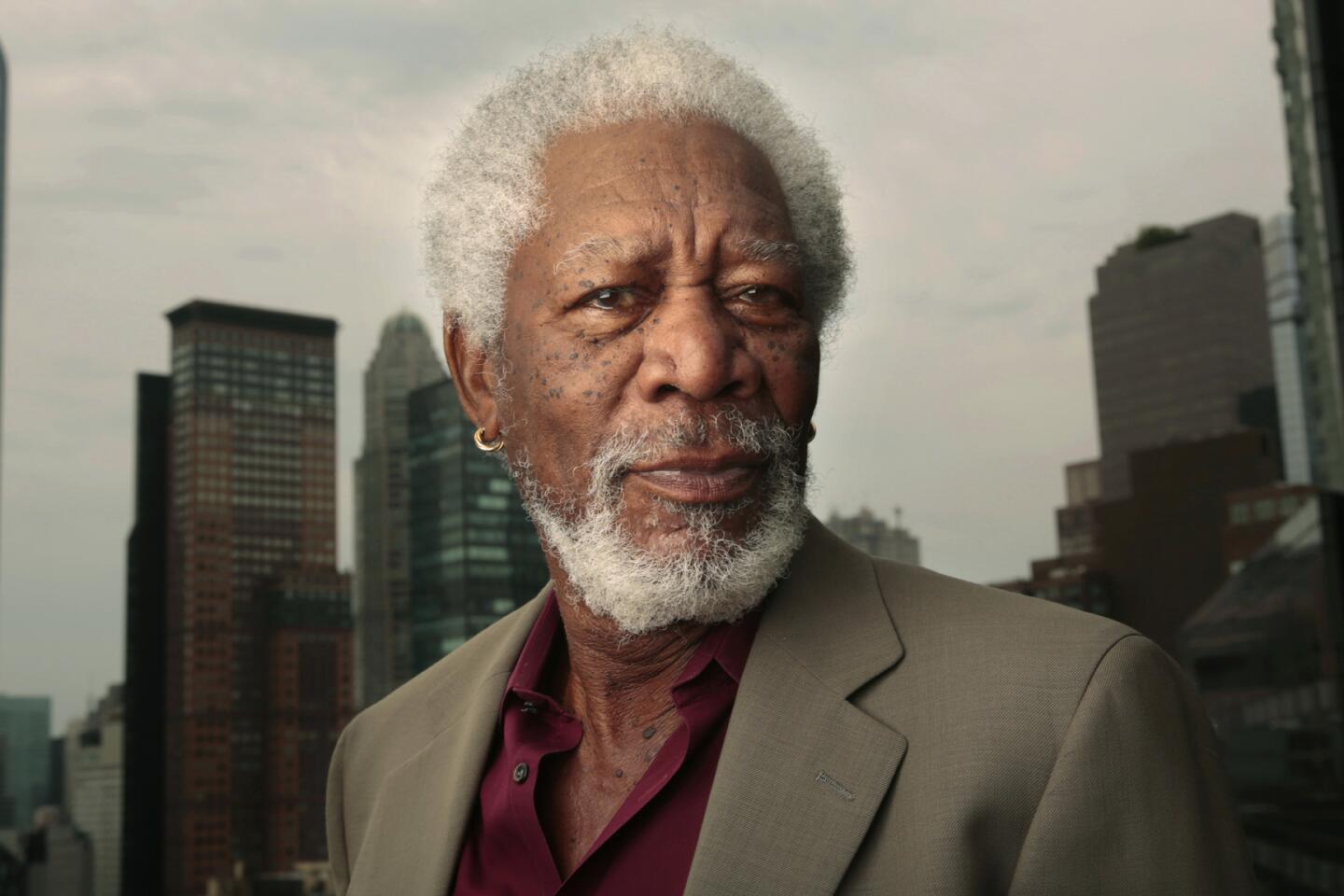

From filmmaker Pratibha Parmar, who first worked with Walker on the 1993 documentary about female circumcision “Warrior Marks,” “Beauty in Truth” reminds us how singular and extraordinary Walker’s life and work remain. She is a woman who speaks softly, writes beautifully, draws strength from nature and regularly empowers and infuriates large groups of people.

BEST TV OF 2013 Lloyd | McNamara

“People really had a problem with my disinterest in submission,” she says early on in the film. “They had a problem with my intellect, and they had a problem with my choice of lovers. They had a problem with my choice of everything.”

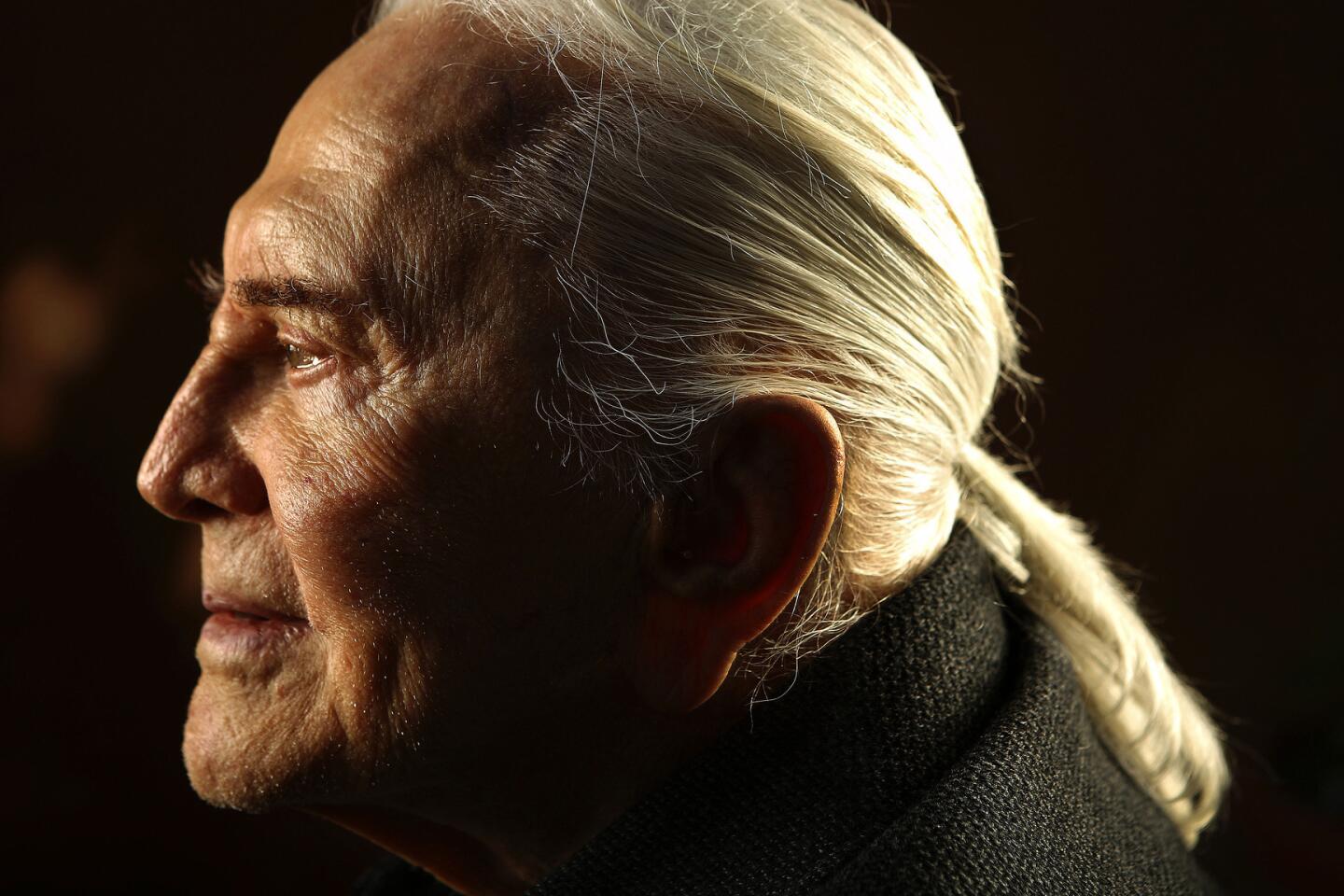

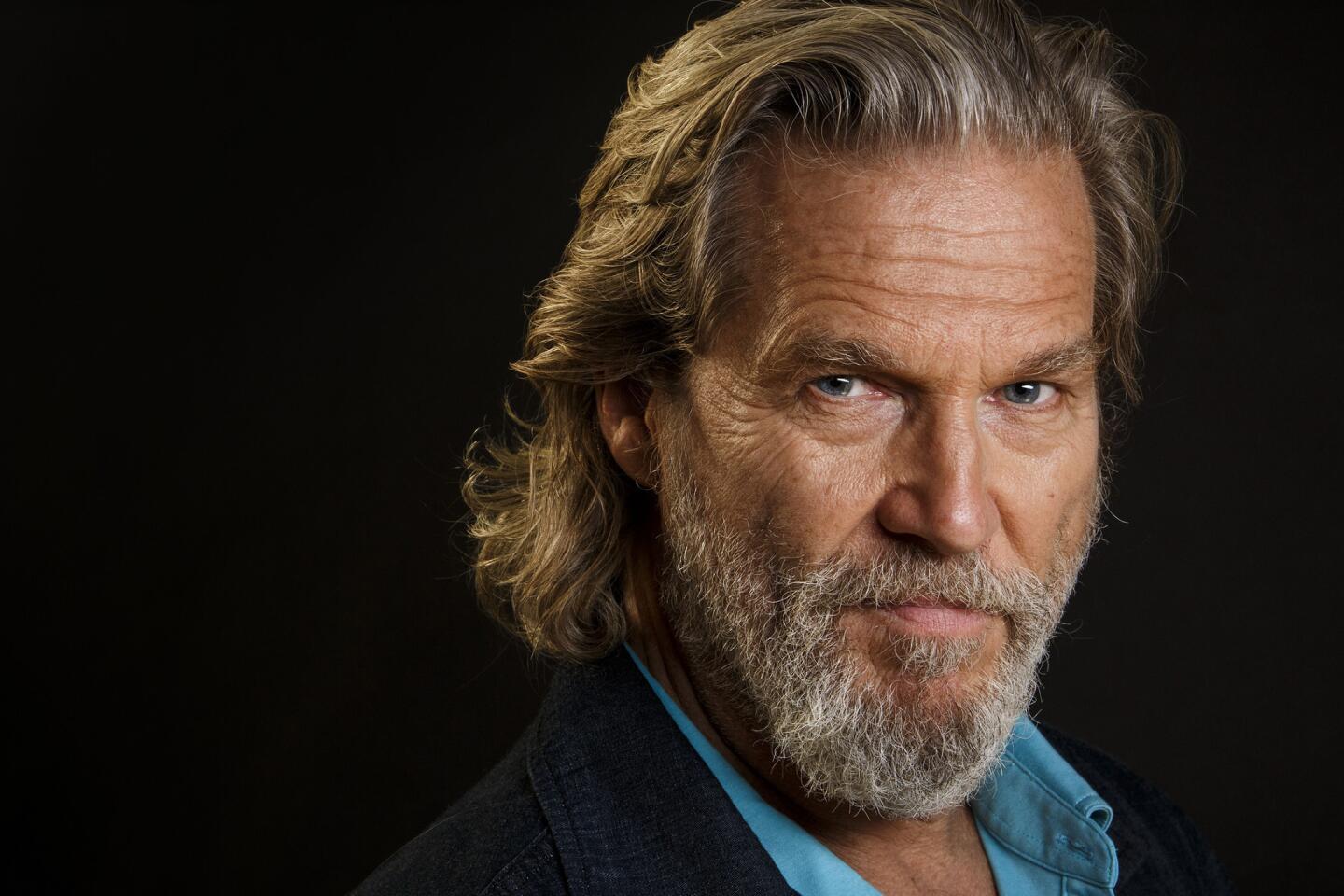

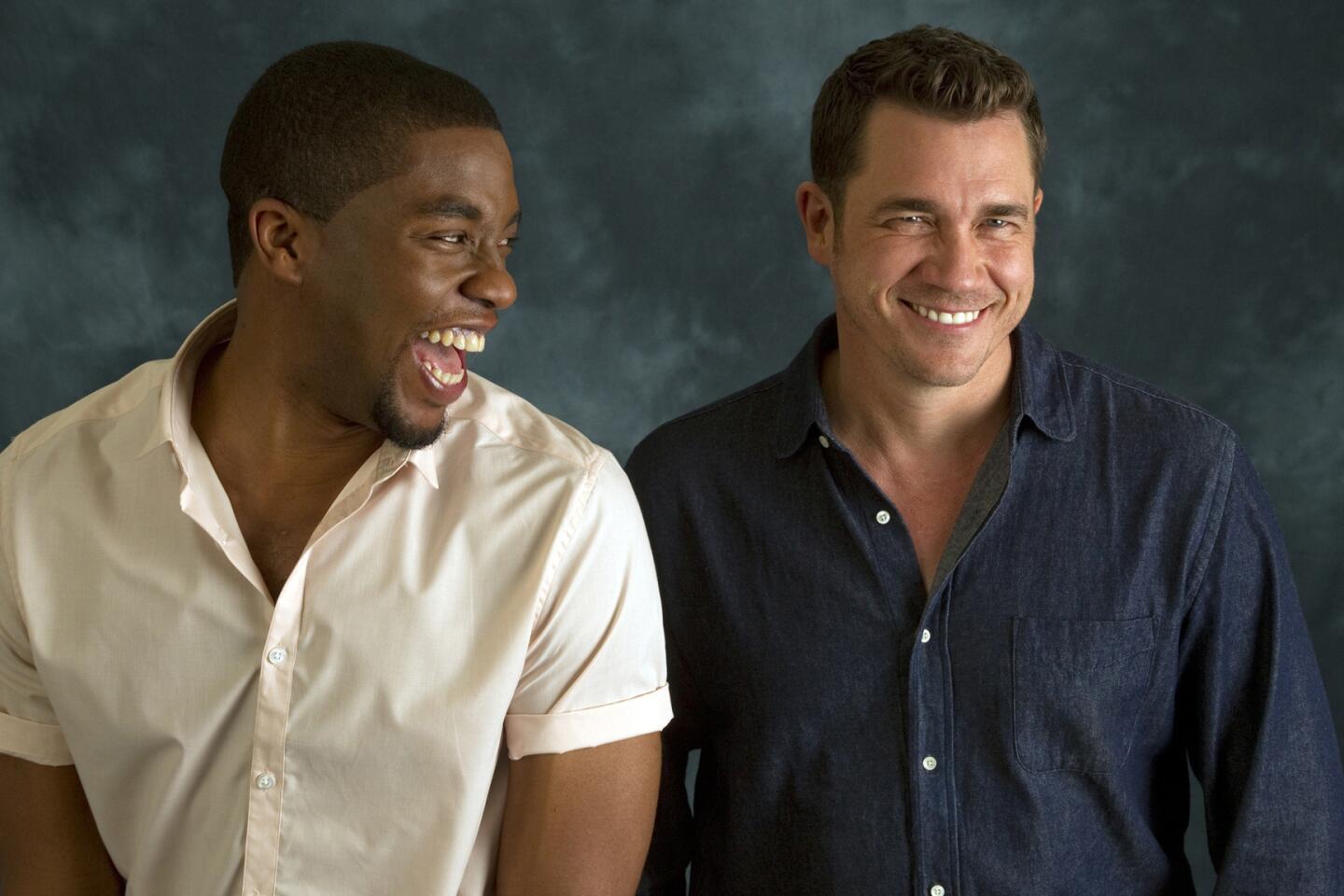

Sharecroppers descended from slaves, Walker’s parents had ambitions for their children that extended beyond the cotton fields of Georgia, and from the time she was a teenager, Walker knew two things: That she was a writer, and that life in the South was unfair. At Spelman College she met the great educator and activist Howard Zinn (seen here in one of the last interviews of his life) and joined the civil rights movement.

But even within those ranks, she went her own way, marrying a white lawyer, Melvyn Leventhal, at a time when such a marriage was illegal in many states. The two had a daughter, Rebecca, but the marriage could not survive the changing times.

PHOTOS: Faces to watch 2014 | TV

As Walker rose to prominence as a poet and novelist, certain factions of the civil rights movement became increasingly exclusionary — Leventhal says he no longer felt welcome at his wife’s readings, and eventually they ended the marriage.

“I felt it would be better for her,” says Leventhal, who speaks at length, and with great fondness, about Walker here.

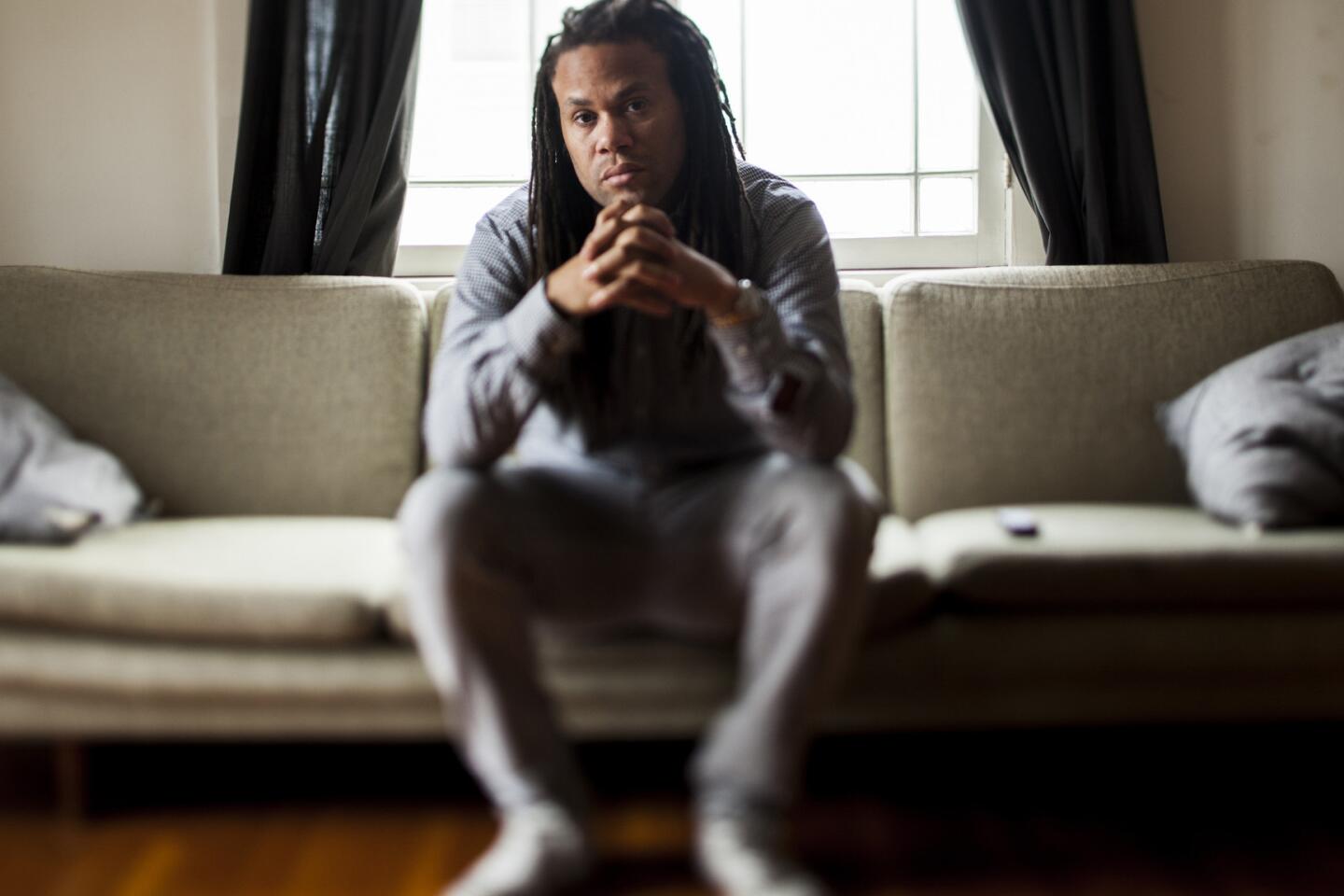

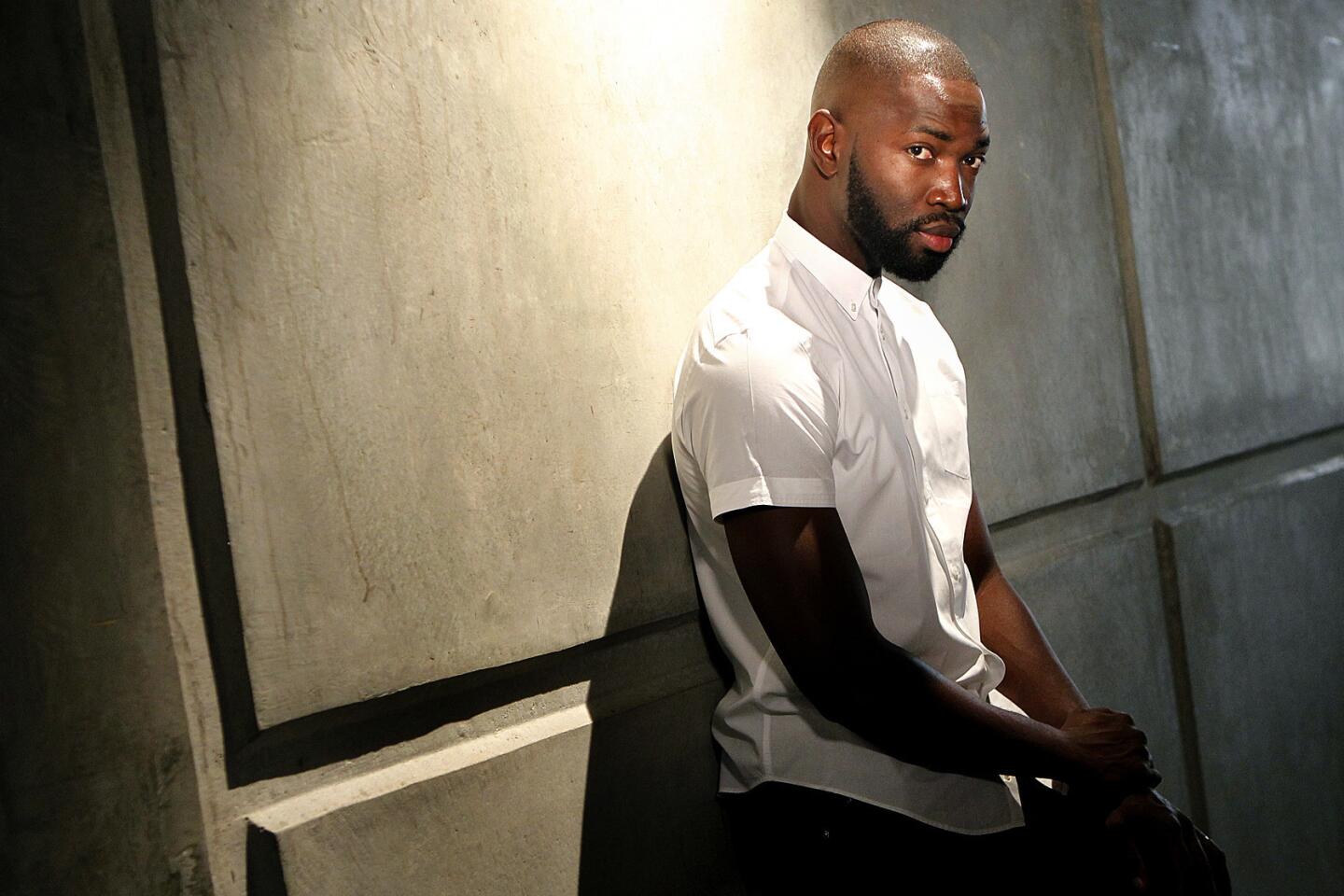

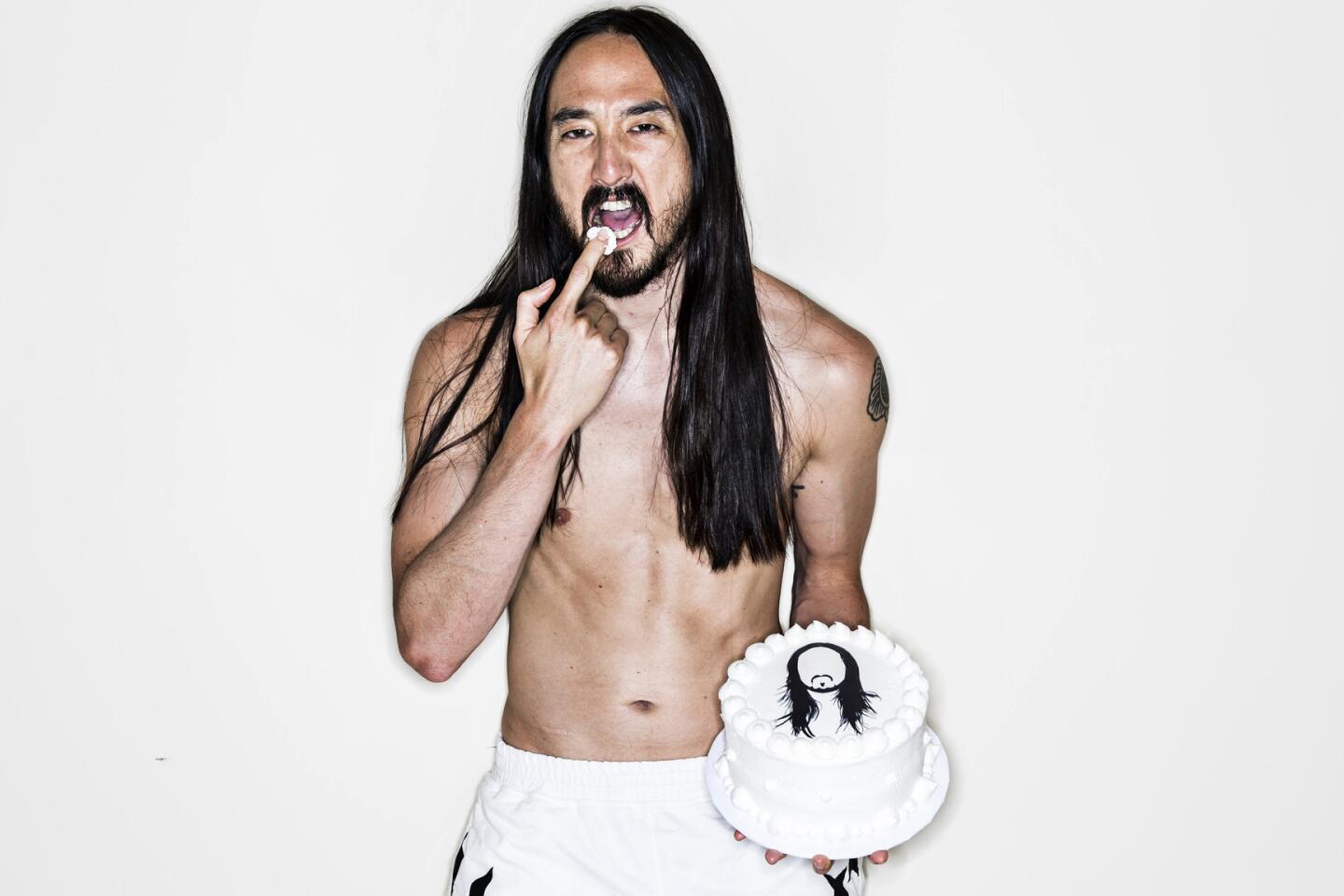

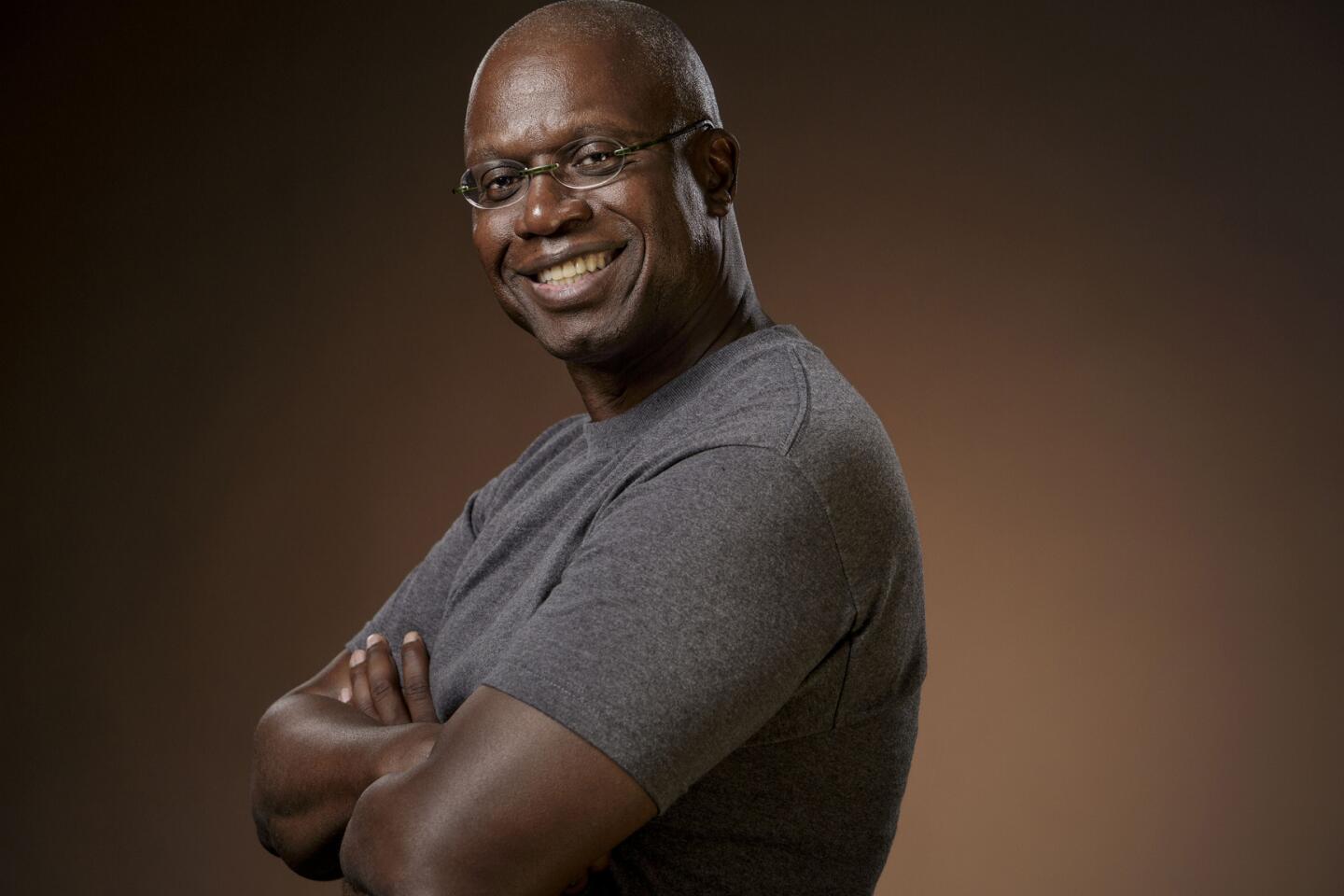

Indeed, everyone speaks with great fondness about Walker in “Beauty in Truth,” including Gloria Steinem, Danny Glover, Angela Davis, Sapphire and Steven Spielberg. This, of course, was not the case when she was making a name for herself, writing novels that gave voice to black women who were too often treated as second-class citizens by both the feminist and civil rights movements.

WINTER TV PREVIEW: Full coverage of the season’s shows

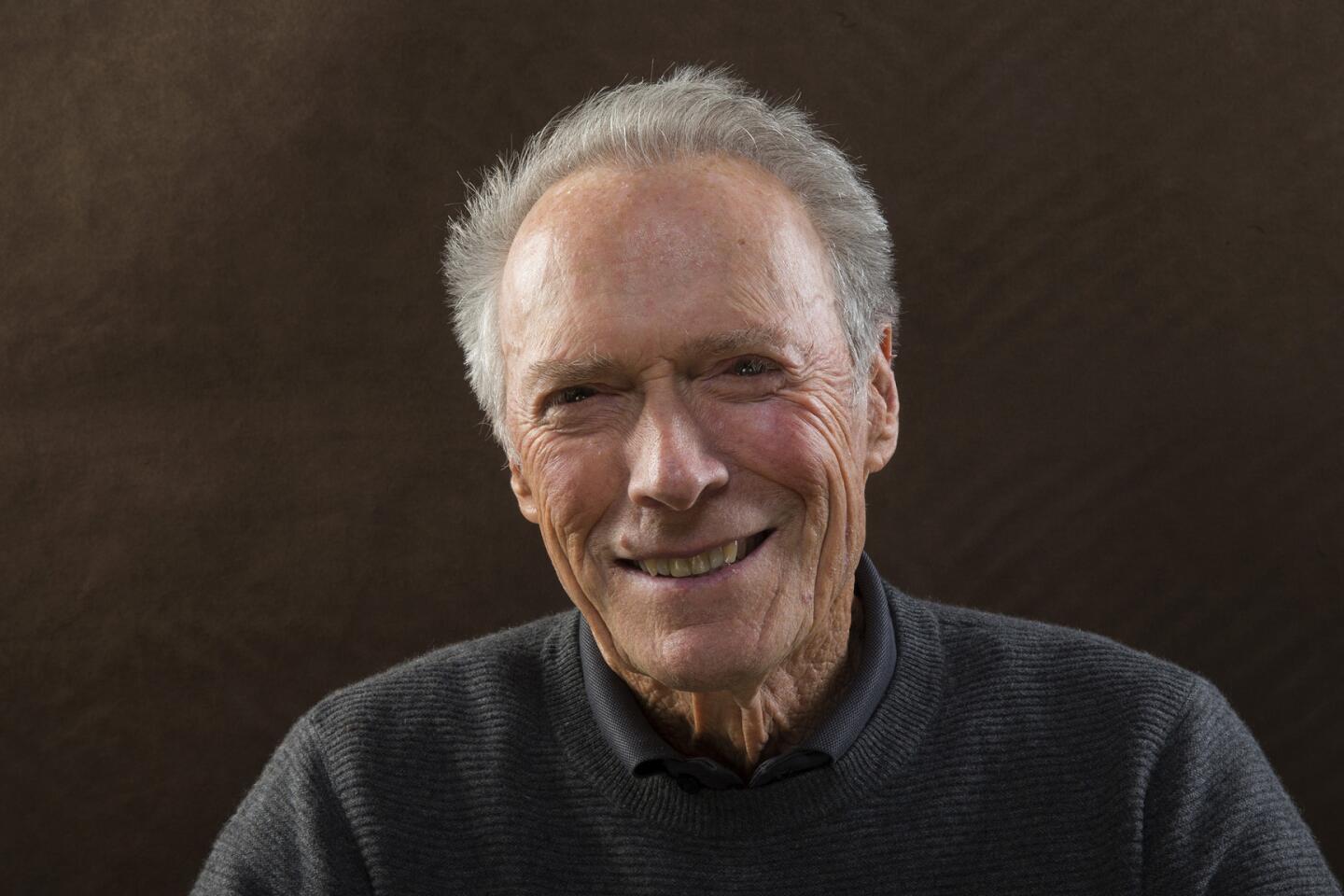

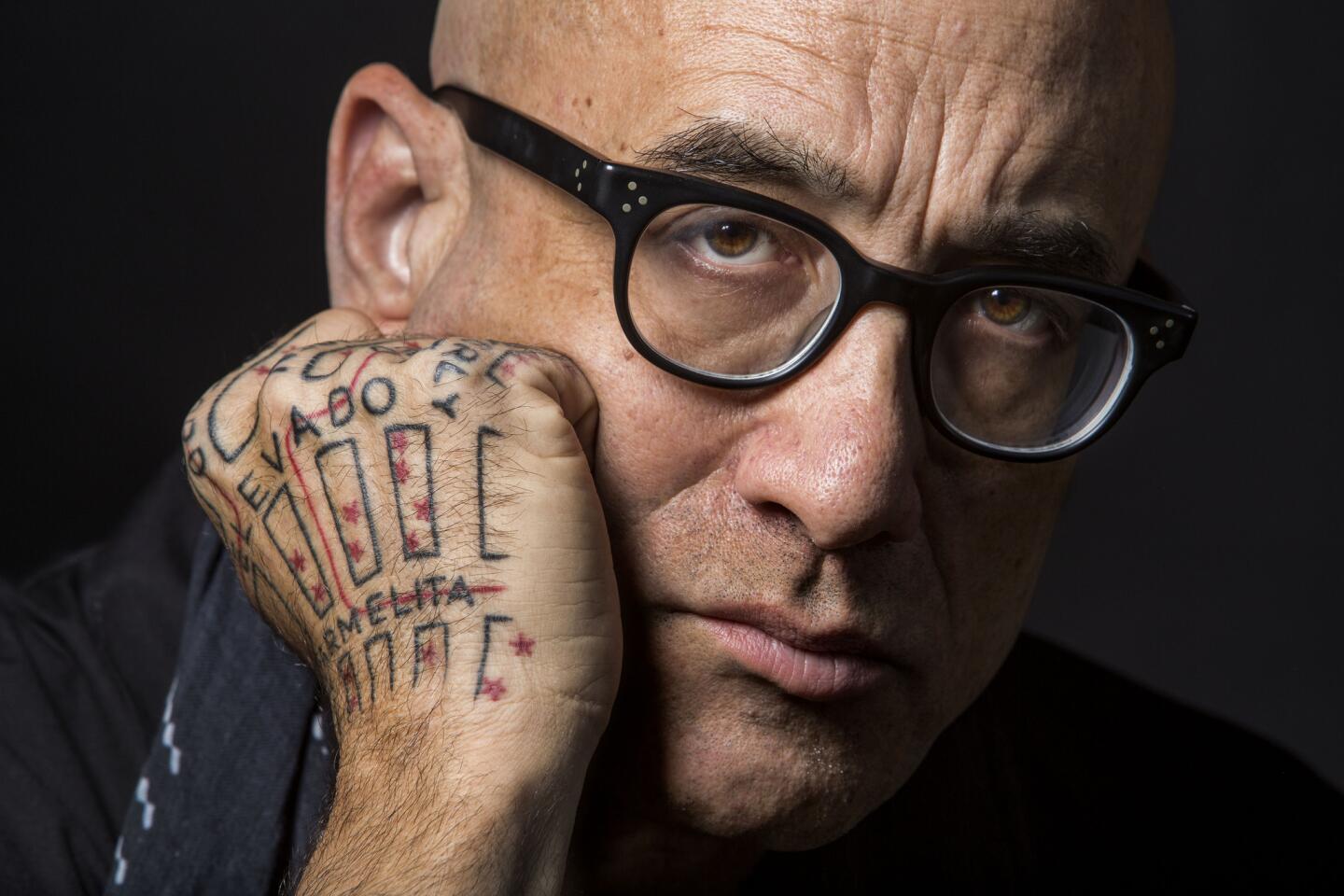

In doing so Walker was embraced by some as a visionary and rejected by others as a firebrand, as her most famous novel, “The Color Purple,” made abundantly clear. The book, which centers around the abuse the protagonist suffers at the hands of her father and then husband before finding love with a woman, won the Pulitzer and National Book Award. But the film on which it was based was condemned by many as a racist depiction of black men and black families.

Walker’s subsequent condemnation of female circumcision in Africa likewise drew as much criticism as it did praise, as has her more recent work on behalf of Palestinian rights. Her personal life, which has included relationships with men and women, only increased her image as someone who refuses to be categorized, drawing champions and detractors including, in the second camp, her own daughter.

In 2008, Rebecca Walker publicly denounced her mother, writing a piece for the Daily Mail in which she accused Walker of neglect and excoriated feminism as anti-motherhood. In “Beauty in Truth,” Walker speaks of having “lost” her daughter; as of the film’s completion, she had not met her grandchild.

All of this is chronicled with remarkable lightness of touch amid glowing praise for Walker’s work and the tranquil beauty of her home. Surrounded by trees and gardens in which Walker finds peace, Walker’s life now presents both sharp contrast and surprising similarities to the images of her familial house in Georgia, where the poverty is clear, but also the natural beauty and the hope.

Hope is what fuels Walker’s work, and what bridges the gap between truth and beauty. Parmar has clearly come to praise Walker, and no doubt there are many other sides to the issues addressed here (Walker’s daughter, for instance, declined to participate.)

The praise is more than due, and it isn’t often we get to spend time with a person of such conviction under whose hands words bloom with both beauty and power. But then there really isn’t another person like this. There’s only Alice Walker.

-------------------------------

‘American Masters’

Where: KOCE

When: 9 p.m. Friday

Rating: TV-PG-L (may be unsuitable for young children with an advisory for coarse language)

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.