Column: Meet John Curtis, the Utah Republican who cares about climate change

Solving climate change would be a hell of a lot easier if the Republican Party would get on board.

Can John Curtis make it happen?

I’ve been reading about the Utah Republican since 2021, when he founded the Conservative Climate Caucus in the U.S. House of Representatives and began making the case that the GOP should take global warming seriously. When he announced this month that he’s running for the Senate, my curiosity finally got the better of me: Should I be taking this guy seriously?

So I reached out to his office and set up an interview.

You're reading Boiling Point

Sammy Roth gets you up to speed on climate change, energy and the environment. Sign up to get it in your inbox twice a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

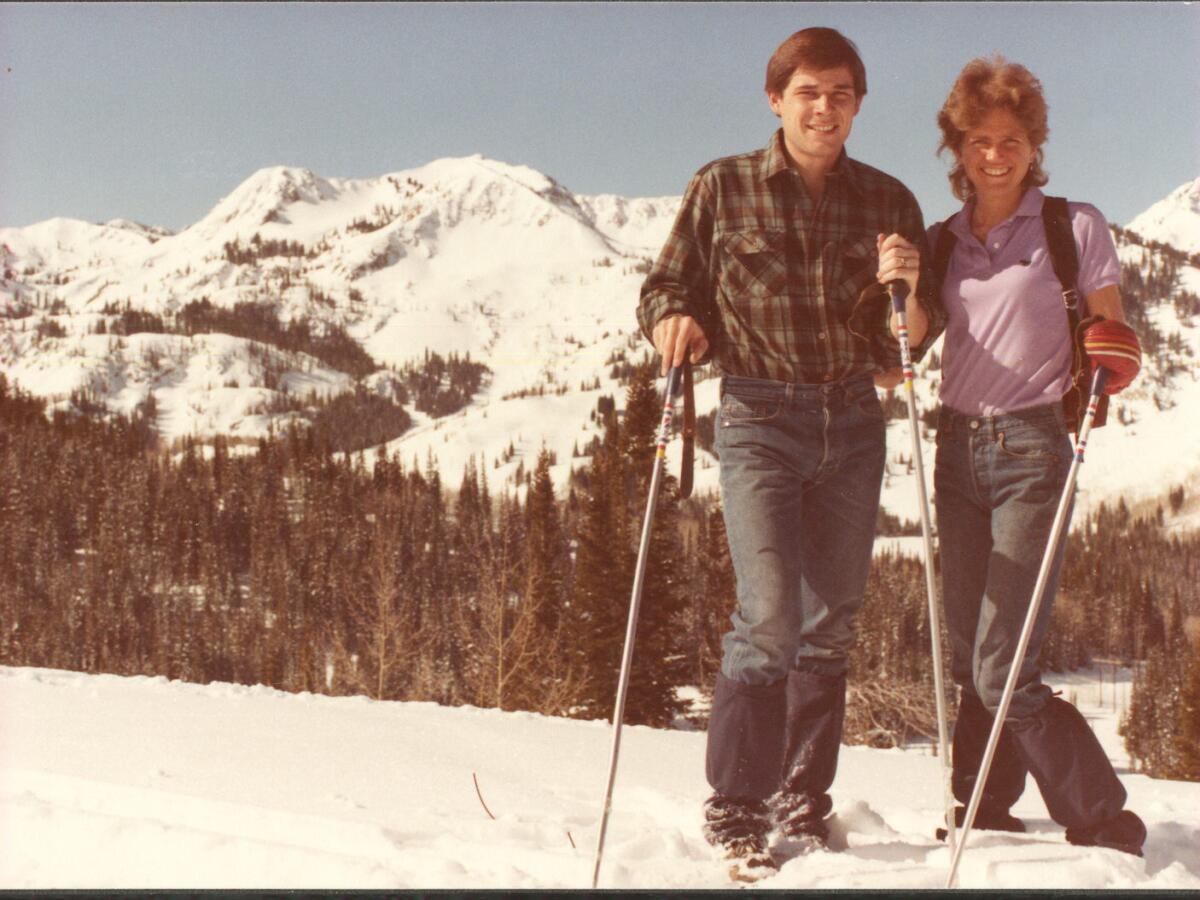

Curtis was gracious with his time, spending more than 45 minutes on the phone answering my questions and explaining how he’d chosen to make the climate crisis a focus of his political life. He started off telling me how he grew up hiking in the Uinta Mountains and learning to love the great outdoors. He described Provo — where he served as mayor before being elected to the House in 2017 — as “one of the most beautiful cities on the planet.”

“On a morning like today, you’d wake up and see snowcapped mountains with the blue sky and the sun,” he said. “If you’re not drawn to nature by that, you have no hope, nothing in you that is decent.”

When he arrived in Washington, D.C., he said, he was “confronted face to face with this reputation that somehow Republicans didn’t care, that they denied the science and somehow didn’t want to pass on a better Earth.”

Although that reputation is, in my own view, well-earned — more on that in a minute — Curtis said it “really disturbed” him. So he founded the Conservative Climate Caucus, which today has 81 members — more than one-third of House Republicans.

The caucus is centered on the idea that “climate is changing, and man’s had some influence on it,” Curtis told me. That’s better than climate denial, but it’s also a dramatic understatement, with NASA describing human activity as the “principal cause” of the “unprecedented” warming we’re already experiencing.

And even endorsing Curtis’ weak language isn’t required for caucus members.

“I’m very non-judgmental. I don’t have a litmus test for who gets to be in the caucus,” he said. “If you want to be part of it, I don’t ask you if you can swear to the tenets. I’m just glad you’re coming and learning.”

Skeptical, I brought up the Republican presidential primary debate in August during which just one of eight candidates onstage raised a hand when asked if global warming is caused by humans. Why should anybody take the GOP seriously on climate, given that response?

Curtis’ answer intrigued me.

He started off by saying he’s “not naïve” and knows he has “a lot of work to do.” But he has also seen a shift in the way Republicans talk about climate. If the topic came up in a House committee hearing six years ago, he said, the conversation “quickly moved to a debate about the science.” Today, it “quickly moves to a debate about methods” — i.e., possible solutions.

And as for the presidential candidates refusing to acknowledge the science? Curtis offered the analogy of a timeshare sales pitch where “you have somebody across the table from you who is highly compensated to get you to do something that’s probably not in your best interest.” If the salesperson were to ask him whether he loves his kids, Curtis told me, he would say he doesn’t, “because I know the next question is, ‘Well then why won’t you buy this timeshare?’”

Republican politicians, he said, are similarly conditioned to be “oversensitive” to the climate science question, because “it feels like if you say yes, then the next question is, ‘Well then why won’t you embrace the Green New Deal?’”

It makes sense — but is it really a good excuse?

On the one hand, I’m sympathetic to the idea that Republican leaders need to be brought along gently on climate, given how polarized the issue has become. It’s not hard to understand why so many conservative officials are reticent to be seen as championing a cause long associated with Democrats. Even for Republican politicians who may genuinely accept climate change as an urgent problem, saying so on the campaign trail could lead to defeat by a primary challenger.

On the other hand, it’s at least partly the Republican Party’s fault that climate change is so politically polarized.

Yes, fossil fuel industry campaign contributions have played a big role. So have Fox News and other bombastic media outlets, which spread misinformation about climate and clean energy and punish conservatives who don’t toe the party line.

But rather than push back against those forces, Republicans leaders have embraced and encouraged them.

See James Inhofe, the former GOP senator from Oklahoma who brought a snowball to the Senate floor in an attempt to disprove climate science. Or Rob Bishop, the Utah Republican who previously served with Curtis in the House and once ate a hamburger at a news conference to draw attention to his (false) claim that the Green New Deal would outlaw meat. Or former President Trump, who won the Iowa caucuses this week and continues to tell wild lies about renewable energy.

So yes, there are some Republican politicians ready to talk climate solutions. And that’s great.

But America’s handful of conservative climate champions have been claiming for years that the party is finally shifting toward taking global warming seriously — and so far, it hasn’t happened. Not a single Republican in Congress voted for the Inflation Reduction Act, the landmark climate bill signed by President Biden. And it’s overwhelmingly likely that the party’s next candidate for president will dismiss the climate crisis as either a hoax or a trifle.

Let’s get back to Curtis, though, and what he might be able to accomplish.

To his credit, he really does wants to persuade his fellow Republicans there are clean energy solutions they can feel good about supporting. Those solutions include “emerging technologies” such as hydrogen fuel that doesn’t produce planet-warming carbon emissions when burned, and “direct air capture” machines that pull carbon from the atmosphere. Curtis is also optimistic about startups working to develop small nuclear reactors that would help keep the lights on 24 hours a day.

He even sees a bright future for solar and wind power.

“Republicans don’t have any problems with renewables,” he said.

I’m not so sure about that, given the renewable-bashing lies spewed by Trump and other prominent Republicans — many of whom falsely claimed that wind turbines caused the terrible blackouts three years ago in Texas, for instance.

I was similarly skeptical of Curtis’ argument that fossil fuels can help solve the climate crisis.

When I asked him what he makes of in-depth studies concluding the U.S. can power its economy without fossil fuels — or with small amounts of oil and gas supplementing solar, wind and other clean energy sources — he said government shouldn’t be in the business of “predetermining” how we tackle climate change. Fossil fuel companies, he said, should have an opportunity to compete, by figuring out ways to capture and bury carbon emissions before they reach the atmosphere.

“Do you hate emissions, or do you hate fossil fuels?” Curtis asked.

It’s a reasonable question — or it would be if climate change were our only problem.

Power plants fueled by coal and natural gas, and cars that run on oil, don’t just emit heat-trapping carbon dioxide and methane gas. They also spew air pollutants that damage our hearts and lungs, especially in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. Fossil fuels can leak from pipelines into the ocean, harm wildlife at drilling sites and foul our drinking water.

And even if we could look beyond those harms, trusting fossil fuel companies to clean up their carbon act would be risky.

For decades, Exxon Mobil and some of its peers funded campaigns to convince the public that climate change wasn’t real, even as their own scientists helped prove that it was. That’s a big reason why global carbon pollution has continued to rise, 36 years after scientist James Hansen famously warned Congress that global warming had begun.

If not for the fossil fuel industry’s profit-driven intransigence, we wouldn’t be faced with the daunting task of cutting emissions 43% over the next six years, which scientists say is necessary to avoid the worst consequences of the climate crisis.

Given that history, should we really trust coal, oil and gas companies to develop affordable carbon-capture devices fast enough to stem the climate threat? If we let them keep operating as usual instead of replacing their products with clean energy as quickly as possible, isn’t there a strong chance that a decade from now we’ll have blown through our carbon budget and locked in a world of wildfires, heat waves, droughts, storms and floods even deadlier and more destructive than the ones we know today?

I posed those questions to Curtis.

“Those are fair thoughts. And my response to that would be, let’s debate,” he said. “Let’s have these conversations.”

It’s a noble sentiment: informed debate, based on science and reason. I’d love to believe it’s possible.

“Instead of Democrats standing back and saying, ‘You’re not sincere,’ or Republicans standing back and saying, ‘This isn’t a problem,’ what we need is to be at the table with sleeves rolled up having this debate,” Curtis said.

Again, it would be a hell of a lot easier to solve climate change with GOP support. Even a handful of the party’s votes in Congress would go a long way toward easing the path to much-needed additional funding for clean energy initiatives.

Curtis is right that there are areas where Democrats and Republicans might see eye to eye — at least some Democrats and some Republicans. Those areas include carbon capture, next-generation nuclear reactors and hydrogen, as well as “permitting reform” that makes it easier to get approval for solar farms and wind turbines on public lands.

Those strategies are controversial among climate activists. But they could become grounds for bipartisan compromise.

“This is what I’m all about, is helping Republicans understand that there are options out there that you can can feel very comfortable with,” Curtis said.

That’s hardly a recipe for keeping global warming under control. Not when time is so short, or the stakes so high.

It is, however, a worthwhile step. A small step, and 36 years too late. But a step nonetheless.

I’m not endorsing all of Curtis’ ideas. A decade of reporting on energy has convinced me that fossil fuels won’t save the day.

But I found myself nodding along as Curtis told me about the coal-dependent communities in his district, including the appropriately named Carbon County. He talked about the coal-mining jobs that have sustained families for generations. About how demeaned those families feel when they hear out-of-town politicians talk about retraining them for new occupations.

“They are the same people who for decades sacrificed their safety and their health so that all of us could walk over to a wall and flip a switch and turn the lights on, or turn the heat to 70, or win a world war,” Curtis said.

The people of Carbon County “see where the market is going,” he added. And although they’ll fight to protect their fossil-fueled way of life if there are no alternatives, they’re willing to consider alternatives. There’s “not a coal town in the world that wouldn’t leap to replace their coal plant with a nuclear facility, because it’s much higher-paying jobs,” Curtis said.

Now the groups and politicians working to accelerate the energy transition need to bring those towns into the conversation.

“So much of what they have heard from the environmental movement is that they are bad people,” Curtis said.

That kind of rhetoric needs to end. Coal miners are just trying to keep their jobs. Climate change isn’t their fault.

It’s not China’s fault either, by the way — at least not entirely. As much as Republicans like to suggest that the U.S. bears little responsibility for cutting climate pollution until China stops building so many coal plants — a tactic Curtis used in our interview — the reality is that America has emitted more carbon dioxide over the years than any other nation. Absolutely, China needs to stop building coal plants. But the U.S. should be leading the world on climate, even as we push other countries to keep up.

As our interview came to a close, I asked Curtis one more time about the presidential election. If his party nominates a candidate who insists that climate change isn’t real — or that we don’t have to worry about it — how will he respond?

“The best answer I can give you is, I’m going to mobilize House Republicans to do it right. That’s what I have control over,” he said. “I can’t control the candidate you’re talking about. As a matter of fact, the more I would try, the less successful I would be.”

I wasn’t satisfied by that answer, but I understood it. Curtis is playing the long game. I hope he succeeds.

But until then, waiting for the Republican Party to join the climate fight is a losing proposition.

On that note, here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

The Biden administration has for the first time given tentative approval for an oil company to capture and store carbon emissions underground in California. Is it time we embrace carbon storage? Or is this just an excuse for oil companies to keep polluting? My L.A. Times colleague Tony Briscoe addresses those questions in his story, which focuses on carbon-capture efforts in Kern County, the heavily polluted heart of California oil country. The Times’ Erika D. Smith, meanwhile, has a column asking a related question: What good is winning the fight for racial equality if climate change delivers misery to everyone, people of color most of all? There’s a new L.A. radio station making the case that environmental justice is racial justice, Erika writes.

With California facing a huge budget deficit, Gov. Gavin Newsom wants to cut several billion dollars in climate spending. My colleague Hayley Smith broke down which climate programs Newsom has proposed for cuts. Ironically, one reason the state finds itself so short on cash is the growing intensity of storms and floods worsened by global warming, as noted here by Times columnist Anita Chabria. Also in Sacramento, a progressive California lawmaker has divested her personal finances from Big Oil after an L.A. Times investigation spotlighted her fossil fuel investments. Details here from Mackenzie Mays.

It’s official: 2023 was Earth’s warmest year on record, ending with seven months of record-breaking heat. We’re drawing ever closer to 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming, Hayley Smith reports. For more startling numbers, check out this story from Yale Climate Connections, which notes there were just 51 daily record lows in the contiguous U.S. last month — compared with 3,408 record highs. And even though much of the United States has been freezing the last few days while other nations bake, the cold spell is probably climate change at work, as the Associated Press’ Seth Borenstein explains.

WATER IN THE WEST

It’s not just the American Southwest losing snow as the planet warms — although we’ve endured some of the biggest losses so far. A new study sheds light on one of the most significant harms from climate change, finding that snowpack across the Northern Hemisphere has shrunk significantly over the last 40 years, threatening water supplies for millions of people, The Times’ Hayley Smith writes. We definitely need to consume less water. But is California asking cities to conserve more than they can reasonably afford, while letting farmers — who use much more water — get off easy? My colleague Ian James takes a look.

Water is flowing freely again through the Klamath River along the California-Oregon border, as several aging dams begin to come down. The San Francisco Chronicle’s Kurtis Alexander wrote about the latest progress along the waterway, describing it as “the culmination of a decades-long push by Native Americans, environmentalists and fishermen to bring the 250-mile Klamath River back to its natural state.” In Colorado, meanwhile, a town has appointed two legal guardians to protect a beloved creek. It’s the first time humans will serve as legal guardians for nature in the U.S., Katie Surma reports for Inside Climate News.

A new study finds that bottled water contains a lot more plastic particles than previously thought — and most of them are “nanoplastics” so small they can cross the blood-brain barrier. If that’s not horrifying, I don’t know what is. Details here from The Times’ Corinne Purtill and Susanne Rust, if you can stomach them. For a bit of a pick-me-up, my colleague Carly Olson wrote about a company that will help you dispose of your hard-to-recycle trash. In other good news, wine and liquor bottles are now redeemable at California recycling centers, Jeremy Childs reports.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

Yes, President Biden broke his campaign promise to end oil and gas drilling on federal lands — but that doesn’t diminish his strong record on climate, Western environmental journalist Jonathan P. Thompson says. I enjoy Thompson’s Land Desk newsletter and found this edition to be thoughtful and provocative. Biden continued his climate work last week with a proposal for the first-ever federal price on carbon pollution. Oil and gas companies will be charged for excess methane emissions, as the New York Times’ Lisa Friedman reports. The Biden administration is also handing out nearly $1 billion for electric school buses, and hundreds of millions more for electric vehicle chargers — including money for fast chargers at Northern California libraries.

A campaign to force Los Angeles to add more bike lanes, bus lanes and wider sidewalks is ramping up. Voters will have a chance to decide at the ballot box on March 5, per my L.A. Times colleague Rachel Uranga. State officials, meanwhile, are asking technology companies to propose strategies for using artificial intelligence to reduce traffic congestion, road deaths and climate pollution, Queenie Wong reports. Some experts are skeptical, with one saying to The Times’ Ryan Fonseca, “You’re telling me we need advanced AI to figure out that it doesn’t do much good to widen the f—ing road?”

Cynthia McClain-Hill has resigned as president of the L.A. Department of Water and Power, amid ethics concerns. Here’s the story from my colleague Dakota Smith, who previously wrote about the ethics concerns with fellow Times journalist Richard Winton. DWP’s next president, to be chosen by Mayor Karen Bass, will help determine whether Los Angeles achieves its goal of 100% clean energy by 2035 — as will Bass’ choice for DWP’s next general manger. That search is ongoing, as I wrote last month.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

California already has some of the nation’s worst roads. As drivers switch to electric cars, how will the state keep paying for road repairs, which have long been funded by gasoline taxes? The Times’ Russ Mitchell tackled that question in his latest story, looking at proposals to charge drivers based on miles traveled. This is definitely a good problem to have. But as great as it is that more people are driving electric vehicles, auto companies are also selling so many SUVs that the average fuel efficiency of new U.S. vehicles is barely improving, the Washington Post’s Nicolás Rivero reports. In other bad news for clean transit, rental car company Hertz is backtracking on its electric vehicles goals, making plans to sell off 20,000 EVs — and use some of the proceeds to buy more gasoline-powered cars, Bloomberg’s David Welch and Richard Clough report.

New buildings in California that use natural gas will no longer receive any subsidies from utility companies. That’s the result of a recent vote by the California Public Utilities Commission, part of the state’s efforts to shift homes and businesses to electric heating and cooking, Utility Dive’s Ysabelle Kempe reports. Not long after that vote, though, the commission rejected a proposal from Southern California Edison to charge its customers about $700 million to support the installation of electric heat pumps in low-income homes, saying the plan would raise electricity bills too much, Politico’s Camille von Kaenel reports.

Battery storage on the U.S. electric grid is projected to grow by another 80% this year, after doubling the last two years and tripling the year before that. That is some crazy growth, detailed here by Canary Media’s Julian Spector and Maria Virginia Olano. In other good news for renewable energy, Emma Foehringer Merchant wrote for Latitude Media about new technologies — some of which use artificial intelligence — that could help bring down the “soft costs” of building solar farms.

AROUND THE WEST

Uranium mining is getting started 10 miles south of the Grand Canyon, within the boundaries of a national monument — and thanks to the General Mining Act of 1872, there’s nothing Native American tribes or other critics can do to stop it. The Arizona Republic’s Debra Utacia Krol has the story, which to environmentalists is the latest sign that the 152-year-old law needs to be updated. In Idaho, meanwhile, a proposed antimony mine could help fuel the batteries needed to support clean energy — and also pollute sacred waterways where salmon are already struggling, the Arizona Republic’s Brandon Loomis reports.

Mexico has broken ground on a wastewater treatment plant in Baja California that should lead to fewer raw sewage flows shutting down San Diego County beaches. It’s a long-awaited victory in the struggle to reduce cross-border pollution, per the San Diego Union-Tribune’s Tammy Murga. In another pollution battle a few hundred miles north, the Biden administration will study the air-quality impacts from a planned highway expansion in California’s heavily polluted San Joaquin Valley, in the wake of great reporting from Fresnoland’s Gregory Weaver highlighting what critics see as failures by state officials.

“I’ve been running cameras for just over five years in southern Arizona and in the deserts hoping maybe one day I’d find a jaguar. It finally happened.” It’s always cool when a jaguar makes its way north across the U.S.-Mexico border, and the latest one is no exception. It’s the eighth jaguar spotted in the wild in the U.S. since the 1990s, my colleague Andrew J. Campa reports.

ONE MORE THING

Thanks much to everyone who came out to the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures for last weekend’s screening of “The Wave,” followed by my discussion with the Surfrider Foundation’s Chad Nelsen about how climate change is portrayed on screen.

The museum’s natural disaster film series continues tonight (Thursday) with “The Day After Tomorrow,” after which my colleague Rosanna Xia will talk with UCLA climate scientist Alex Hall. I’m discussing “Deep Impact” this Saturday night with UCLA’s Stephanie Pincetl, and The Times’ Hayley Smith will chat with earthquake expert Lucy Jones after “San Andreas” on Friday, Jan. 26.

Again, you can get your tickets here.

This column is the latest edition of Boiling Point, an email newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. You can sign up for Boiling Point here. And for more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on X.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.