As drought worsens, tensions erupt over control of SoCal’s largest water supplier

- Share via

Southern California’s biggest water supplier has chosen a new general manager — but the selection isn’t yet final, and the fiercely contested vote is exposing deep disagreements within the powerful agency as a severe drought grips the region.

The Metropolitan Water District’s board of directors voted this month to select Adel Hagekhalil to lead the agency, The Times has learned, replacing longtime head honcho Jeff Kightlinger, who is retiring. Hagekhalil runs L.A.’s Bureau of Street Services and was previously second-in-command at the city’s sanitation department.

Metropolitan finds itself at a crossroads after 15 years under Kightlinger’s leadership. The agency delivers huge amounts of water from the Colorado River and Northern California, and has prided itself on hammering out complex deals to protect the region’s water rights and investments. But those far-flung resources are becoming less dependable as the planet heats up.

In Los Angeles, Hagekhalil has played a key role in Mayor Eric Garcetti’s plans to limit reliance on water imports by recycling sewage water and capturing stormwater before it reaches the ocean. His selection could mark at least a partial shift in focus for Metropolitan, and a fresh start for an agency that has been rocked by allegations of sexual harassment.

But the agency’s board needs to vote again to formally offer him a contract — and Hagekhalil’s supporters are worried there could be an effort to derail his candidacy by Kightlinger or board members who preferred another applicant.

Several directors who supported Hagekhalil have gotten calls from their colleagues questioning whether he’s really the best choice, according to multiple people familiar with the behind-the-scenes struggle. A memo distributed to the board by the agency’s human resources director after the vote referred to Hagekhalil only as the “leading candidate,” saying he still needed to go through a background check, a review of his references and a discussion about pay before an offer could be made.

Council President Nury Martinez requested a report on the city’s relationship with the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California after a Times article detailed a pattern of accusations from women who worked there.

Hagekhalil’s detractors see him as too inexperienced in Western water politics to lead an agency whose work makes life possible in Southern California, especially as climate change brings higher temperatures, more evaporation and diminished snowpack.

They’ve rallied around Pat Mulroy, a legendary figure in the Colorado River Basin. During her 20-plus years leading the Southern Nevada Water Authority, Mulroy helped the Las Vegas Valley grow substantially despite limited water rights by urging aggressive conservation and driving a hard bargain with surrounding states and the federal government.

She also at times championed a 300-mile pipeline to rural eastern Nevada that would have allowed Las Vegas to draw on remote groundwater reserves — the kind of sprawling water supply infrastructure that was built across the West in the 20th century, but which many environmentalists see as folly. The project was ultimately defeated.

Mulroy placed second among six candidates in the Metropolitan board’s vote, according to a confidential tally obtained by The Times. She actually won 18 votes compared to Hagekhalil’s 16. But under the agency’s weighted voting system — in which larger cities and water districts have a larger say — Hagekhalil won a 50.4% majority, compared to Mulroy’s 46.8%.

The vote took place in a non-public “closed session” on May 8, as allowed for hiring decisions under state law. An agency official announced afterward that the board “made a selection for general manager and provided direction on contract negotiation.”

Both of the top vote-getters declined to comment for this story, as did Kightlinger.

The Metropolitan Water District is relatively little known among Southern Californians. But it plays a crucial role in the lives and livelihoods of nearly 19 million people in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego and Ventura counties.

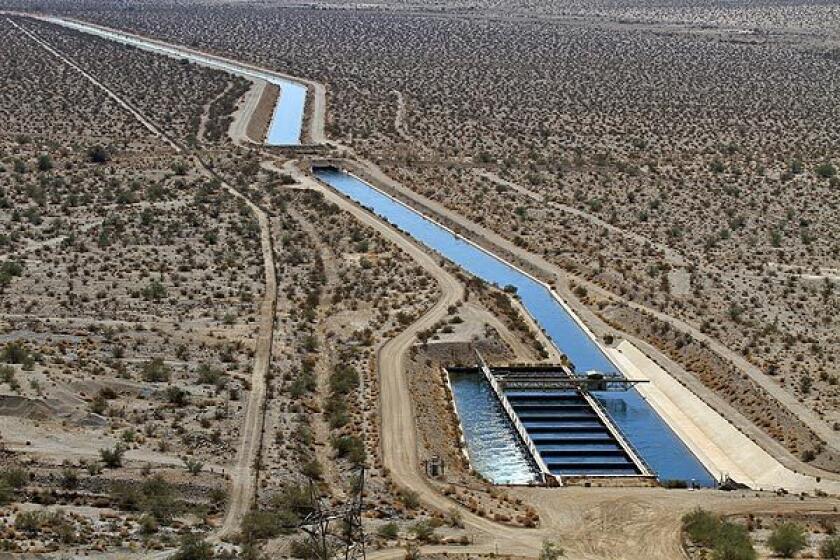

From its 12-story headquarters next door to Union Station in downtown L.A., the 1,800-employee agency operates the 242-mile Colorado River aqueduct, a thin blue strip through the desert that brings water to sinks, showerheads, swimming pools and golf courses. It’s a powerful player in state politics, buying much of the water that’s pumped south from Northern California rivers and lobbying aggressively for a controversial $16-billion tunnel near the Bay Area that would help keep that water flowing.

Your guide to our clean energy future

Get our Boiling Point newsletter for the latest on the power sector, water wars and more — and what they mean for California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Los Angeles is one of the agency’s largest customers, getting half of its water from Metropolitan on average in recent years. The city also imports water from the Owens Valley and Mono Basin through the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

But L.A. hopes to produce more water through recycling and stormwater capture, and to use that supply more efficiently. Garcetti set a goal of sourcing 70% of the city’s water locally by 2035, in part by cleaning and reusing 100% of its wastewater.

Hagekhalil’s supporters say they expect him to be a strong backer of those types of projects.

“From what I’ve heard about Adel, he seems really open to the environmental perspective and sustainable solutions. He said he wants to work with the community, he wants to work together with folks,” Sierra Club organizer Caty Wagner said.

Metropolitan has started moving in that direction under Kightlinger, paying Southern Californians to tear out their lawns and teaming up with Los Angeles County on plans to build one of the world’s largest sewage purification facilities.

The agency also supports the proposed “Delta Conveyance Project” beneath the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers. Kightlinger has argued the massive tunnel is needed to keep water flowing south as environmental rules limit pumping. Opponents say it would be ecologically devastating, and an expensive distraction from sustainable local supplies.

Conner Everts, executive director of the Southern California Watershed Alliance, said he supports Hagekhalil because Metropolitan needs a new perspective on “what a water agency is in this century, and how it works differently than it has in the past, when the focus was on bringing on supply.” The key challenges are shifting, he said, as per-person water use falls due to conservation, protecting biodiversity becomes more important and climate change intensifies the swings between drought and flood.

Lake Mead is just 39% full as critical negotiations between California and other Western states get underway.

Garcetti appointed five of Metropolitan’s 38 board members, more than any of the 25 other cities and water districts the agency serves. All five voted for Hagekhalil, although it wasn’t only Garcetti loyalists supporting him. He also received votes from board members representing Fullerton, Glendale, Long Beach, San Diego County, San Fernando, Santa Ana and Santa Monica.

Mulroy’s backers were concentrated in Orange County and the Inland Empire, with additional support coming from water providers in the San Gabriel Valley, Ventura County, Compton, Pasadena and Torrance. Her most high-profile supporter was Metropolitan Chairwoman Gloria Gray, who represents West Basin Municipal Water District in L.A. County.

Supporters see Mulroy as far more experienced than Hagekhalil in the hard-fought battles that are only getting tougher as climate change saps the Colorado River and the Sierra Nevada snowpack, which feeds California’s major rivers and reservoirs. She oversaw a 45% reduction in per-person water use in Southern Nevada between 2000 and 2014 and struck several deals to save water for dry times, in part by returning treated wastewater to Lake Mead that can then be retrieved later.

“She’s very well-spoken. She’s very articulate. She’s one of the ones who spoke most about climate change,” said a person familiar with the candidate selection process. With Hagekhalil, the person added, “there would be a very steep learning curve.”

Mulroy’s experience could be especially valuable as the seven states that draw on the Colorado gear up to renegotiate their century-old water-sharing pact ahead of a 2026 deadline, and as the water that can be sent south from California’s Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers is limited by environmental rules meant to protect salmon and other struggling fish.

Mulroy has already done work for Metropolitan since retiring from her job in Nevada. From March 2016 through February 2021, she consulted for the agency on federal policy, climate change, endangered species and other issues, according to contracts obtained by The Times. Her consulting firm was paid $10,000 per month, with the contracts approved by Kightlinger’s office.

Support our journalism

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

Hagekhalil’s skeptics have also raised concerns about lawsuits filed against L.A.’s sanitation bureau during his time at the agency.

One of the suits, involving sexual harassment, resulted in a multimillion-dollar jury verdict but didn’t name or implicate Hagekhalil. In another, filed last year, a city sanitation employee claims Hagekhalil and other officials retaliated against him for testifying in the first suit, and accuses Hagekhalil specifically of “systematic anti-Chicano racist promotional practices and policies.”

In a note distributed to the Metropolitan board two days after they voted for Hagekhalil, an L.A. deputy city attorney wrote that the retaliation suit “does not identify any interactions between the plaintiff and [Hagekhalil] whatsoever, much less any interactions that could be perceived as legally cognizable harassment,” and that the city plans to try to get the case dismissed.

Local 721 of the Service Employees International Union, which represents over 10,000 city workers, sent a letter to the water agency board calling Hagekhalil an “exemplary leader” who has “worked to build a culture of inclusion, respect, and fairness.”

Whoever gets the Metropolitan job, they’ll have their work cut out for them.

The California Department of Water Resources reported this week that Sierra Nevada snowpack is at just 2% of normal levels. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says the 12-month stretch ending April 30 was the driest such period on record in Arizona, Nevada and New Mexico, the second-driest in California and Utah, the third-driest in Wyoming and fourth-driest in Colorado.

Southern California is likely prepared to weather a few dry years, thanks in part to Metropolitan banking record amounts of water in reservoirs including Lake Mead and Diamond Valley Lake, and in underground aquifers. Those reserves were made possible by the agency’s diverse supplies from across the West, and its growing investments in conservation.

California has entered another drought. But depending on who you ask, the last one may have never really ended.

Even if Los Angeles and nearby cities are tremendously successful at recycling sewage water and cutting back on thirsty green lawns, they’ll still likely be heavily dependent on imported water for years to come. Likewise, even the biggest boosters of traditional water infrastructure projects acknowledge that conservation, recycling and capturing stormwater represent a big part of the region’s future. It’s just a question of how much is possible, and how fast.

“We know the pie’s shrinking, and we each have to take a little less,” Kightlinger told The Times last year. “But if there are even small ways we can grow the pie, that helps us all.”