Deadly results as dramatic climate whiplash causes California’s aging levees to fail

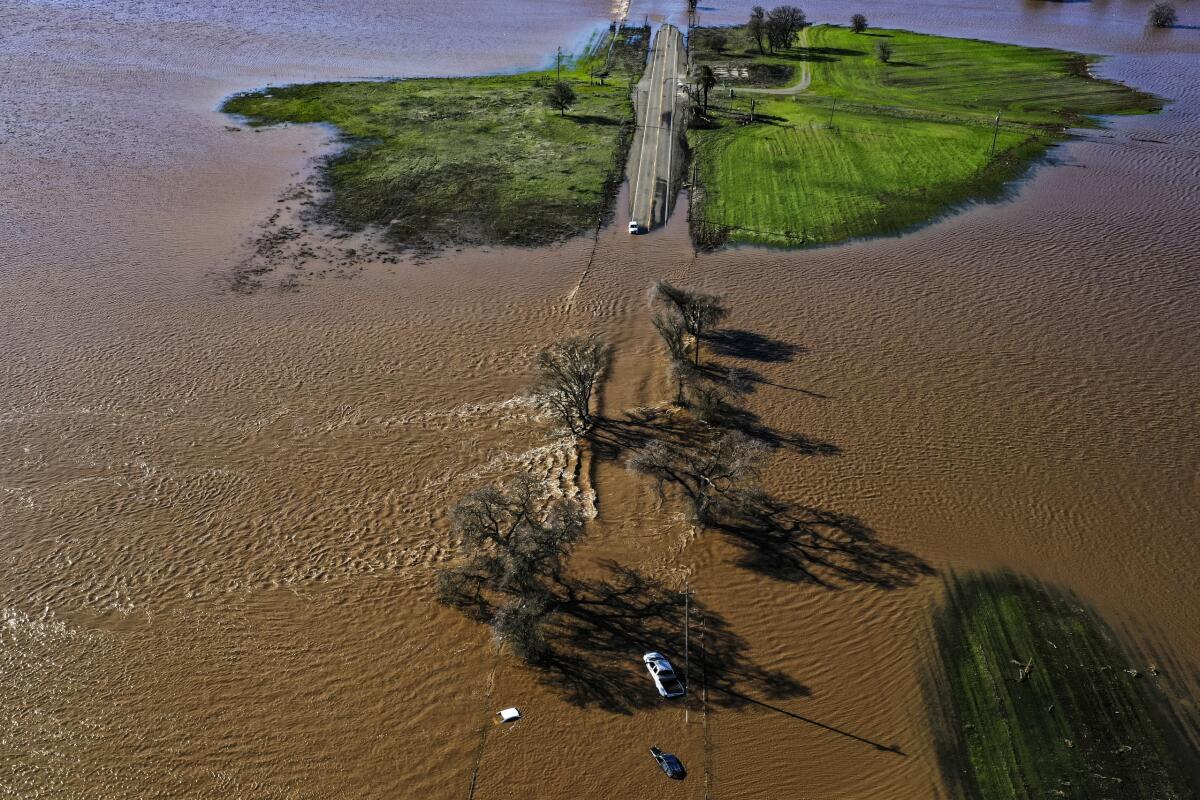

SACRAMENTO — The pounding rains of New Year’s Eve had ceased, but the pastures, freeways and neighborhoods surrounding the tiny community of Wilton continued to disappear beneath a vast, growing ocean of muddy water that left only the roofs of sunken vehicles visible to rescue helicopters.

It was a chilling vision of just how vulnerable California’s network of rural levees has become in an age of climate extremes. By Wednesday, nearly a dozen earthen embankments along the Cosumnes River near Sacramento had been breached, and three people had been found dead inside or next to submerged vehicles.

For the record:

7:03 p.m. Jan. 5, 2023An earlier version of this story said that a 200-year level of flood protection refers to a 2% probability of flooding in a given year. The probability is 0.5%.

Experts say such failures are all but inevitable as California’s aging levee system whipsaws between desiccating drought and intense downpours. Storm water has a nasty way of finding errors in infrastructure planning and design, said Jeffrey Mount, a geomorphologist and senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California.

“There are two kinds of levees: Those that have failed, and those that will fail,” said Mount.

As California was hit by yet another “brutal” storm system Wednesday, Mount and others warned that lack of maintenance and changing hydrology would increase flood risk in the coming years. At the same time, Department of Water Resources director Karla Nemeth warned that rural levees would be the “most vulnerable places in California,” largely because they are not required to meet the same standards as levees that protect more urban communities.

NASA satellite imagery from December 16, 2022 and January 1, 2023, shows floodwater inundating communities in North-Central California as a series of atmospheric river storms moved through the state.

For those tasked with maintaining levees, upkeep is an exercise in frustration.

Many reclamation districts in the state are charged with meeting requirements for 100-year or 200-year levels of flood protection, referring to a 1% or 0.5% probability of flooding in a given year. But some small rural districts with limited budgets can maintain the levees to only a 10-year flood standard.

“That is practically nothing, but at a budget of $500,000 a year, and 34 miles of levee, that’s about all we can do,” said Mark Hite, a board member of Reclamation District 800, which oversees a stretch of Cosumnes River levees between Wilton and Rancho Murieta.

“I’d like to think we’ve done a pretty damn good job, but we get some of these extraordinary events, like a 100-year or a 200-year event, and we’ve got problems,” he added.

Of three major breaks in his district, the largest is believed to span about 300 feet, although there’s still too much water in the area to say for sure, he said. All of the levee issues occurred on private land.

The intense downpours — coming after an earlier deluge days ago — pushed some rivers toward flood stage, prompting a string of evacuations from towns along the Russian River to communities in Santa Cruz County and beyond.

On Wednesday, Nemeth told reporters that the state and federal government are partway through construction of a $1.85-billion flood protection project that will help shore up some of the levees along the Sacramento and American rivers.

“We’re making good progress, but when we have these kinds of systems, it’s very easy for smaller communities to get overwhelmed,” she said. About 361 miles of urban and 120 miles of non-urban levees have been repaired or improved since 2007, according to the state’s Central Valley Flood Protection Plan.

But as the latest storm arrived, the Sacramento River churned angrily, brown with debris and roiling with white caps across its usually calm surface on Wednesday. In Clarksburg, along the river’s edge, residents have been without power since the previous storm on New Year’s Eve brought down dozens of power lines.

Susan Roork stopped by the area’s only open store. She said she and her husband are “keeping an eye on every agency website we can” to monitor the storm, the rising river and the strength of the levee.

The powerful storm that knocked out power, toppled trees — including one that killed a toddler — and flooded homes along the coast in Santa Cruz continued its march through the region.

Down the street, Sandy Adams Jr., the pastor of the Clarksburg Community Church, said he took comfort from knowing his local levee district had recently reinforced the berm. He worried more about the lack of power and flooding from torrential rain.

Concern over the viability of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta’s 1,100-mile maze of earthen levees has been percolating for years. In 2005, Mount published a paper that predicted a 2-in-3 chance that a major earthquake or storm would cause widespread levee failures in the delta over the next 50 years.

That forecast, combined with visceral images of the destruction caused by failed levees during Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans earlier that year, prompted federal legislation and local tax increases to generate funds needed to make critical improvements in certain areas.

But those upgrades, which far exceeded federal safety requirements at the time, Mount said, were not enough to keep pace with weather conditions changing at a rate that only a decade ago was unimaginable.

In the meantime, urban growth is bringing thousands of people closer to the vulnerable levee system.

California ‘storm train’ may rival notorious El Niño winter of 1997–98

Scientists and policymakers are looking warily at another trend: The whiplash effects of a heating planet, where increasing temperatures allow the atmosphere to absorb and store more and more moisture.

This phenomenon can result in either a massive release of water in the form of an atmospheric river or extreme drought and aridity.

“We know that climate change is supercharging this extreme weather,” California Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot said during Wednesday’s news conference. “We find ourselves in the third year of an intense drought — and in fact the last three years have been the driest three-year period in the state’s history. And at the same time, of course, now we navigate this series of atmospheric rivers.”

The Central Valley flood plan similarly notes that “thousands of miles of levees in the Central Valley were not designed, constructed or maintained to withstand extreme events.”

Mount added that part of the problem is that persistent drought conditions have “always made Californians forget about major storms and our deteriorating flood control systems.” He said there is growing concern that rising sea levels, deteriorating levees, ongoing subsidence and creeping urbanization are making it all but impossible to make the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta flood-proof and safe.

It all adds up to what he describes as “The Great Paradox”: The repairs needed to protect communities, farmland and a major source of drinking water for more than 20 million Californians could take decades to design, approve, fund and build.

By then, the damage and risks they aimed to reduce would have been surpassed by the likelihood of weather conditions unleashing a deluge as devastating as the Great Flood of 1862. In that event, 30 consecutive days of rain triggered massive flooding across much of the state.

When will California storms hit hardest and how long will they last?

A similar storm today, scientists say, would displace up to 10 million people, shut down major freeways such as Interstates 5 and 80 for months, and inundate Stockton, Fresno and portions of Los Angeles.

On Wednesday, officials were increasingly anxious about the incoming storm and the possibility that more will follow.

With much of the state on flood alert, water managers have been consulting with one another in daily teleconferences, and juggling what is flowing in and out of some reservoirs as part of an effort to absorb runoff from incoming storms.

“Are we prepared for this weather?” said Jay Lund, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at UC Davis. “Somewhat. But more than a thousand linear miles of levees in a sorry state, means there’s a lot more expensive preparation ahead of us.”