2022 tied for the fifth-hottest year on record, NASA says

In what has become a grim annual tradition, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced Thursday that 2022 was one of the warmest years in modern recorded history.

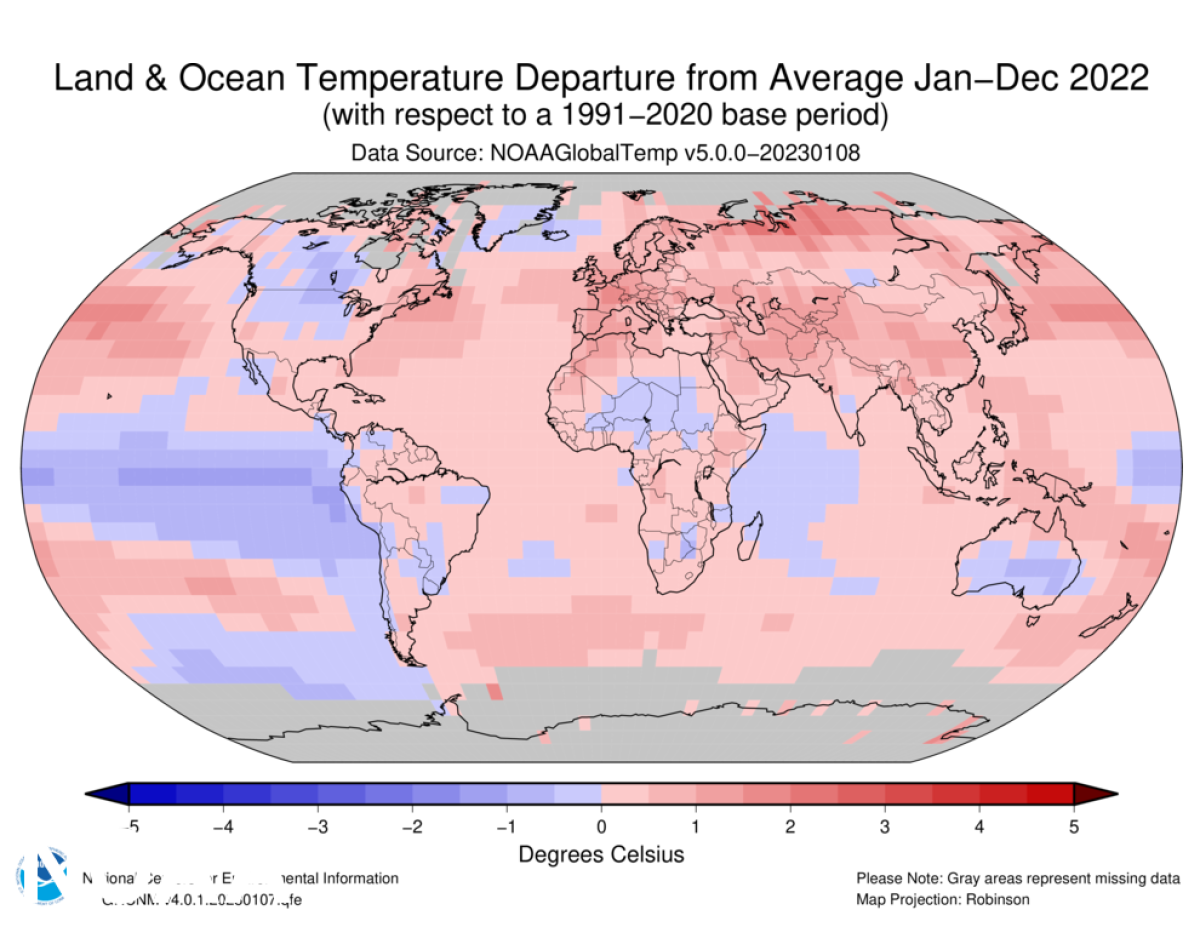

According to NOAA’s measurements of global temperature data, 2022 ranked as the planet’s sixth-warmest year on record. By NASA’s slightly different accounting it tied for the fifth-hottest year, sharing that “alarming distinction” with 2015, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said.

“That’s pretty alarming,” Nelson said. “And that’s a trend that is growing in magnitude.”

The data for 2022 confirm that nine of the last 10 years have been the warmest since 1880, when the government began keeping records. This was despite the ongoing La Niña event, which typically has a cooling effect on the globe.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Without La Niña’s cooling influence, 2022 would have been the second-warmest year on record, said NASA climatologist Gavin Schmidt.

NOAA said the planet’s average global temperature last year was just 0.4 of a degree Fahrenheit higher than the year before. But it was more than 1.5 degrees warmer than the average for the entire 20th century.

NOAA doesn’t include Antarctica and the Arctic in its calculations. If it did, it would have agreed with NASA that 2022 qualified as the fifth-warmest year, NOAA said.

The agencies’ reports are just the latest confirmation of a global climate trend that manages to be at once astonishing and dismally predictable.

The European Union’s climate change service also confirmed this week that last summer was Europe’s hottest ever, breaking the record set in 2021. With the exception of Iceland, the continent as a whole experienced its second-hottest year in 2022, with many Western European nations recording their warmest ever years.

Russell Vose, chief of climate monitoring for the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, gave 2022 a “99% chance” of ranking in the 10 warmest years on record when releasing last year’s report from his agency.

He was right. Not only did 2022 easily make the top 10, it was the 46th consecutive year of global temperatures that exceeded the 20th century average. The planet hasn’t had a colder-than-average year since Gerald Ford was president.

The European climate service described 2022 as the planet’s fifth-warmest year since its records began, behind 2016, 2020, 2019 and 2017. The average temperature last year was nearly 2.2 degrees higher than the preindustrial period of 1850 to 1900, before humanity began emitting heat-trapping greenhouse gases at a furious rate. It was even 0.54 of a degree higher than average for the already warm decades between 1991 and 2020.

Europe is facing one of its worst droughts ever, as rivers dry up, farms go fallow and vineyards roast.

China experienced the most severe heat wave in its modern recorded history last summer, with more than 900 million people subjected to temperatures above 104 degrees for more than 70 days.

India and Pakistan weathered debilitating heat in March and April, followed by record-breaking rainfall in July and August. The subsequent floods displaced 33 million people in Pakistan and killed 1,700.

And here in California, a September heat wave shattered temperature records across the state and nearly broke the power grid.

“What we’re seeing is our warming climate, it’s warning all of us,” Nelson said. “Forest fires are intensifying. Hurricanes are getting stronger. Droughts are wreaking havoc. Sea levels are rising. Extreme weather patterns threaten our well-being across this planet.”

As sweaty as it was on the most populated continents, the world’s biggest temperature surges were at the poles.

Parts of Antarctica on Friday hit 70 degrees warmer than normal.

Extreme heat swept Antarctica in March, sending temperatures above the continent’s eastern ice sheet soaring 50 to 90 degrees above normal. At Vostok Station, where the coldest temperature on Earth was recorded in 1983, the temperature hit 0.4 degrees on March 18 — chilly, yes, but still a full 27 degrees higher than the next-warmest March day to date.

A similar story played out on the planet’s other side.

The Arctic is warming three times faster than the central part of the globe, Schmidt said Thursday. Last year saw a 10% decrease in peak Arctic sea ice and a 40% decrease in sea ice cover in the warmer month of September. Ice around the North Pole neared or reached its melting point at a time once considered unthinkably early.

“They are opposite seasons. You don’t see the North and the South [poles] both melting at the same time,” ice scientist Walt Meier of the National Snow and Ice Data Center said last year when the Antarctic heat wave was underway. “It’s definitely an unusual occurrence.”

The world’s glaciers are shrinking and disappearing faster than scientists thought, but limiting global warming by even a little would help save them.

The temperature of the world’s oceans hit a record high in 2022. Changes in the ocean occur over centuries, Vose said Thursday, so the seas haven’t heated as quickly as the atmosphere, even though they’ve absorbed more heat.

The oceans absorbed roughly 10 additional zettajoules of energy between 2021 and 2022, a recent study found. To get an idea of just how much heat that is, consider that the entire world generated about 0.5 of a zettajoule of electricity in 2021.

“If it wasn’t for the large storage capacity of the ocean, the atmosphere would have warmed more already,” Vose said. Ocean heat doesn’t really fluctuate year to year, he added: “It just keeps stacking up.”

Read all of our coverage about how California is neglecting the climate threat posed by extreme heat.

Last year was also the third-costliest year for climate disasters in U.S. history, with damage from floods, storms, heat and other extreme events costing more than $165 billion, said Sarah Kapnick, NOAA’s chief scientist.

For climate scientists, the agencies’ news was disheartening, if expected.

“None of this comes as a surprise in our bumpy ride uphill to a warmer world,” UC Merced climatologist John Abatzoglou said.

“Global climate is like a symphony,” he said, and “factors like El Niño and human-caused cumulative emissions are instruments in the symphony. La Niña years are low notes, but the drum of human-caused climate change continues to beat louder and louder.”

The drum of human-caused climate change continues to beat louder and louder.

— UC Merced climatologist John Abatzoglou

The warming is a direct result of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, the NOAA and NASA researchers agreed.

Preliminary data released Tuesday by the research firm Rhodium Group show that U.S. greenhouse gas emissions were 1.3% higher in 2022 than in 2021. The country looks increasingly unlikely to meet the goal set in the Paris climate accord to reduce its emissions 50% to 52% below 2005 levels by 2030.

But future warming is not a foregone conclusion, Schmidt said. A reduction in greenhouse gas emissions would probably result in lower temperatures.

“It’s never going to be too late to make better decisions. ... As a society, collectively, we still have agency,” Schmidt said. “If we continue emitting at the rate we are now, we are going to continue to warm.”

Vose wrapped up his presentation by sharing a graph of climate records collected by four major agencies — NASA, NOAA, the Hadley Center and Berkeley Earth — going all the way back to 1880. Different methodologies led to minute differences in years such as 2022, he noted, but for the most part the records are in lockstep and moving inexorably upward.

It takes “a heck of a lot of good work to do things in slightly different ways to get the same answer,” he said. “We all tell basically the same story. ... We wish we could tell a different story.”