L.A.’s new water war: Keeping supply from Mono Lake flowing as critics want it cut off

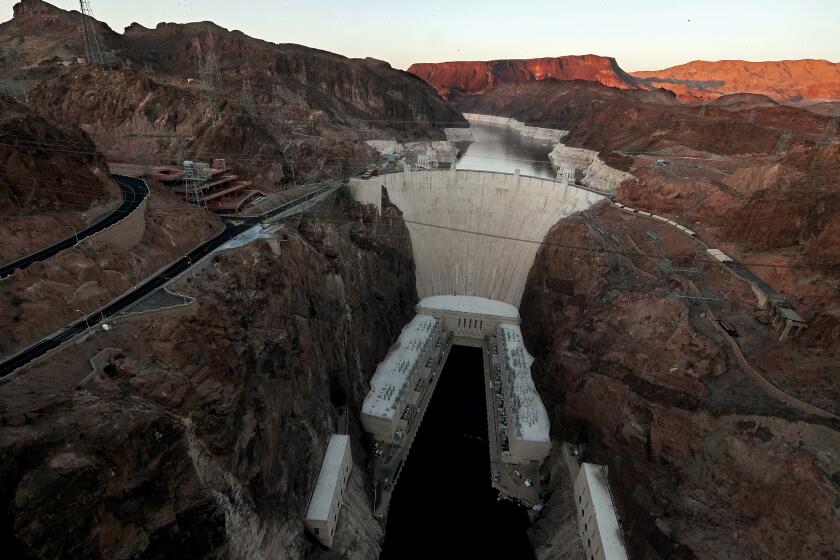

With its haunting rock spires and salt-crusted shores, Mono Lake is a Hollywood vision of the apocalypse. To the city of Los Angeles, however, this Eastern Sierra basin represents the very source of L.A.’s prosperity — the right to free water.

For decades, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power has relied on long-standing water rights to divert from the streams that feed this ancient lake as part of the city’s far-flung water empire. But in the face of global warming, drought and lawsuits from environmentalists, the DWP is now facing the previously unthinkable prospect of ending its diversions there.

In the coming months, the State Water Resources Control Board will decide whether Mono Lake’s declining water level — and the associated ecological impacts — constitute an emergency that outweighs L.A.’s right to divert up to 16,000 acre-feet of supplies each year.

The DWP currently exports 4,500 acre-feet of water from Mono Basin.

Although that is a relatively small quantity of water — about 1% of the city’s total annual supply — the stakes could not be higher for Los Angeles and the vast network of water providers in Southern California. They warn that taking emergency action to prohibit DWP diversions could significantly strain the careful balance of water sources throughout the state.

Adel Hagekhalil, general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, told the water board in a letter recently that were Los Angeles to lose supplies “for whatever reason,” the MWD would “have to draw a similar amount of water from its other imperiled sources to make up the difference.”

That wouldn’t be easy, he said, at a time when “key permitting issues remain unresolved in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, which supplies the State Water Project,” and the Colorado River has yet to reach a consensus on how to curtail water use.

Colorado River in Crisis is a series of stories, videos and podcasts in which Los Angeles Times journalists travel throughout the river’s watershed, from the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the river’s dry delta in Mexico.

For its part, the DWP says Mono Basin water is essential to serving up to 200,000 of its 4 million ratepayers — about half of them living in disadvantaged communities. Purchasing water to replace the lost supplies could cost ratepayers up to $44 million a year, they say.

“Los Angeles residents, and every Californian, have a human right to safe, clean, affordable and accessible water,” the agency said in a prepared statement. “The water from the Los Angeles Aqueduct is the city’s most cost-effective water supply and is the backbone of the city’s water system.”

The water dispute concerns a 1994 order by the State Water Board to restore the level of Mono Lake to 6,392 feet — about 14 feet above the current level.

At a recent water board workshop, environmentalists said L.A. water diversions need to stop until the lake rises at least five feet so that it can provide a drought buffer, reduce salinity levels and protect an island gull rookery from predators.

“Mono Lake is only 25% of the way to the required healthy lake level,” said Geoffrey McQuilkin, executive director of the Mono Lake Committee. “Yet LADWP has taken all the water that was allotted and more, and continues to divert.”

In making a final decision, the board must consider such factors as air quality, brine shrimp and alkali fly populations that feed vast numbers of gulls and migratory birds, recreational opportunities for visitors from around the world, and the spectacular scenery at the base of jagged Sierra Nevada peaks. They must also consider damage caused by Los Angeles to the Mono Lake Kutzadika’a tribe’s ancestral lands and cultural ties to the lake and the five creeks that feed it.

“Our tribal heritage and culture rely upon a lake that is healthy and strong,” Dean Tonenna, a spokesman for the tribe, told the board. “Yet our voice was never factored into any of the decisions having to do with Mono Lake. ... These injustices are exacerbated by climate change and complex water resources and watershed management processes.”

The tribe is also concerned about toxic dust clouds rising off swaths of exposed playa that continue to exceed federal and state law in frequency and magnitude, according to regional air quality officials.

Researchers say flooding from a 100-year storm could impact up to 1 million people in and around Los Angeles, 30 times more than previously estimated.

Anselmo Collins, senior assistant general manager for the DWP’s water system, however, dismissed that kind of talk, saying “there is no emergency at Mono Lake.”

He pointed out that the region’s snowpack is currently 230% above normal and expected to raise Mono Lake’s surface level by at least two feet, “ensuring the continued health of the Mono Basin ecosystem.”

If anything, he argued, conditions at Mono Lake are an example of how the DWP “is leading the state in meeting Gov. Newsom’s climate and conservation goals.”

At a time when lakes and reservoirs across the state are shrinking, he said, the lake’s surface level has held relatively steady, albeit far lower than the level called for by the water board 28 years ago.

The high-quality Mono Basin water that the agency has been diverting south to the city since 1941 through the Los Angeles Aqueduct, he said, “is the least energy-intensive and most cost-effective source of water in Los Angeles.”

That’s because the water is free, except for a $75 treatment cost, and generates hydropower along the way.

By way of comparison, the DWP pays $1,209 per acre-foot of treated water it buys from both the State Water Project and the Colorado River, officials said.

Phillip Kiddoo, air pollution control officer for the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District, agreed, up to a point.

Severe air-quality issues, for example, will persist until the lake level is high enough to permanently submerge a quarter mile of dusty salt flats marking how far the shoreline has retreated since the 1940s, Kiddoo said.

Much of the arguments and questions raised at the workshop focused on Mono Lake’s ecological viability.

Collins rejected claims that a “land bridge” has emerged near islands that host one of the world’s largest nesting populations of California gulls, allowing coyotes to pad across and feast on their eggs.

He presented recent photographic evidence that the gulls’ nesting islands are surrounded by enough water to protect them from coyotes. In addition, he said, the DWP has offered to help pay for barrier fences if necessary.

McQuilkin countered with evidence of his own. The DWP, he said, “asserts that there is no land bridge at Mono Lake, defying the existence of the 500-acre landscape feature I can see out the window.”

Numerous homes that underwent remediation have been left with lead concentrations in excess of state health standards, according to USC researchers.

The DWP’s position is supported by agencies and organizations including the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, the Southern California Water Coalition, the Las Virgenes Water District, the Upper San Gabriel Valley Municipal Water District, the city of Glendale and the Los Angeles County Business Federation.

But Peter Vorster, a hydrogeographer with more than 45 years’ experience in the eastern Sierra Nevada, suggested they’re missing the point.

“Sadly, DWP wants to ignore 40 years of court rulings and water board orders that repeatedly determined that its excessive diversions of cheap water are being extracted at a high cost to the Mono Basin environment,” he said.

Los Angeles’ diversions from Mono Lake’s tributaries resulted in a 45-foot decline in lake level between 1941 and 1982.

Formal protests began with a lawsuit that residents and environmental groups filed in Mono County Superior Court in 1979 against the DWP — an agency distrusted by many in the eastern Sierra Nevada since the turn of the 20th century, when Los Angeles agents posed as ranchers to buy land and water rights in the region.

The suit alleged violations of public trust and the creation of a public and private nuisance by exposing 14,700 acres of former lakebed. The declining water level uncovered a land bridge connecting an island rookery to the shore.

In 1983, the U.S. Supreme Court let stand a ruling that environmentalists had the right to challenge the amount of water Los Angeles was exporting from the tributaries. A decade later, the state water board set the minimum water level for Mono Lake.

Soon after, the lake level began to rise. The best available models at the time predicted the lake would achieve the target elevation in 20 years.

All that changed in 2012 with the onset of a severe five-year drought that caused the lake level to drop sharply. The dry cycle was followed by a snowpack-fueled deluge of runoff that added five feet of water to Mono Lake.

Overall, the lake has stubbornly fluctuated at about 10 to 15 feet below the target level, which environmentalists and air-quality officials believe may be evidence that conditions such as historic precipitation, groundwater flows and evaporation rates are significantly different from those state officials used in 1994.

After so much delay, an enforceable final decision is long overdue, said Felicia Marcus, Landreth Visiting Fellow at Stanford University’s Water in the West Program and a former state water board member.

“The scale of the water involved compared with the scale of the fight over it seems a mismatch,” she said. “But there are not many big water users who have given up water for the environment.”

“This may be an opportunity,” she added, “for Los Angeles to take credit for such a decision.”