Charlie Huston channels his anger in ‘Skinner’

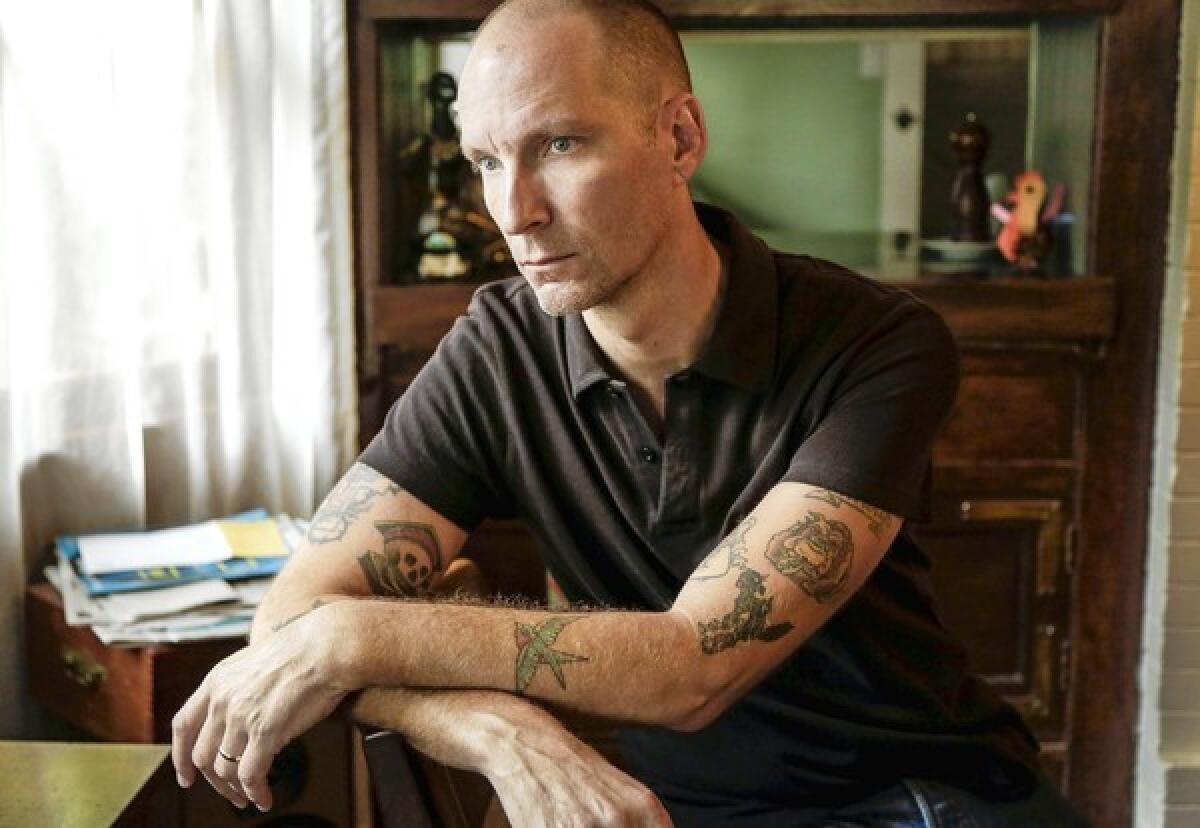

These things have happened in Charlie Huston’s novels: People are shot, strangled, bludgeoned, raped; a cat is tortured; brains are splattered. With his dark imagination, you might expect Huston to be a black-clad, moody goth, or a cigarette-smoking nihilist with a taste for the macabre. Instead, he’s soft-spoken, with a quiet manner and a careful, disciplined bearing.

Discipline is what enabled him to publish 11 novels in eight years, while also writing several Marvel comic books and major TV projects like the “All Signs of Death” pilot with Alan Ball.

Twice an Edgar Award finalist, Huston is known for writing modern, edgy pulp lined with black humor. His latest, “Skinner” (Mulholland, 400pp, $26), is a searingly contemporary, character-driven international thriller built around a mysterious cyber attack that has parallels in today’s news.

“With the NSA and Edward Snowden — I’ve been updating the manuscript as much as I could, but at a certain point I don’t have access to it anymore,” Huston says. “I’ve made jokes about this recently. If you want to write something that’s really on top of current events and have it retain the feel of immediacy, a novel is the worst possible medium in which to do it.”

Yet “Skinner” does seem of-the-moment, such as its mass demonstrations in unexpected cities (not Istanbul, Turkey, but close) and futuristic robotic devices and spy tactics. To deal with a kinetic cyber attack — “a cyber attack that has an actual physical result in the world that causes the loss of infrastructure and death,” Huston rattles off like a seasoned security industry pro — an international security firm calls in two former operatives, Jae, a brainy female hacker and Skinner, an emotionless male agent (read: assassin).

“Initially, he was just going to be this instrument for me to vent anxiety through violence on the page,” Huston says. “I had this idea of writing a grand guignol revenger fantasy.”

Some of this anxiety does come through. In one fight scene, Huston writes: “Skinner shoves several fingers into the man’s mouth, hooking them into his upper palate and pulling. His other hand is already at the left side of the man’s neck, shoving the curved #28 blade of the X-ACTO into his jugular and pulling it across his throat, a moment in which the man is double hinged, neck and mouth both wide open, and then Skinner lets him drop to the floor.” //

“The book was going to be page after page of catharsis,” Houston admits. “I was so angry at politicians, businesspeople, executives, bankers, 1-percenters. Seeing this constant reinforcement of inequity masked as an effort to keep people free and independent. It would fill me with this very visceral, I-want-to-hit-somebody-or-something anger.”

While “Skinner” has its share of bone-crunching fight scenes, Houston channeled that anger into a book with a highly complex picture of how people live at opposite ends of the economic spectrum, private plane-flying spymasters and slum-dwellers without electricity. He says he’s pulled back on the violence. “It’s more alluded to,” he says. “Which suits my sensibility these days.”

Huston works in the front room of the Echo Park Craftsman home he shares with his wife, actress Virginia Louise Smith, and their 5-year-old daughter. The walls are covered with homey artifacts, old photographs and vintage advertisements; his daughter’s room is painted a sweet lavender.

Being a father has led him to try new approaches. “I can’t afford to be pessimistic about the world,” he says. “If I were to let myself sink into despair, I’d be programming my daughter to be someone who can’t see a future for herself. And that’s obviously not an option.”

How parents program children is woven into the book. The character Skinner is so-called because his autistic scientist parents brought him up in a Skinner Box, the (popularly misunderstood) observation box created by psychologist B.F. Skinner. In the book, Huston uses halting language to explore how a person brought up in such unusual circumstances might connect to others and how he might be different from the boys around him.

“I became aware at a certain point in my writing that virtually all of my books feature a brotherly relationship that’s central to what’s going on,” Huston says. “I hadn’t realized it until my sixth, seventh, eighth book. I was like, what is this? I realized I was doing it over and over again.”

Huston explains that he lost his elder brother more than a decade ago. “At the time, it seemed young. Now it seems horribly, horribly young, for him to die at 32,” he says. His brother died in his sleep after struggling with drugs and alcohol.

The two grew up in a happy suburban family — his parents are still together — in Livermore, Calif. Their mother stayed home when they were young, later becoming a teacher and administrator. Their father was a Teamster who drove a forklift; eventually he opened his own motor sport business. Huston absorbed gearhead lessons — he describes the traffic outside his home as “buses and two-stroke motorbikes.”

As we’re sitting on his porch, he steps away to take a call from his agent. Where some writers agonize about the slings and arrows of Hollywood, Huston is exceptionally sanguine about it. “When I’m working on TV, it’s pretty easy to accept that is a collaborative process,” he says. “To some extent, it’s refreshing. I spend a lot of time alone, with no sounding board and no feedback while I’m working.” He’s collaborated with Ball as well as “24’s” Evan Katz and “Justified”’s Michael Dinner on projects that haven’t yet made it to screen.

“Los Angeles has been very good to me. I’m not sure I would have been as capable of redirecting my psychological cant in New York as I was — Los Angeles makes it a little bit easier, for me personally, to get into a way of thinking about the world that isn’t as bleak. There’s a sense of peace. There’s my daughter being born here. Having her makes all the difference.”

And, he says, “I get to write novels.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.