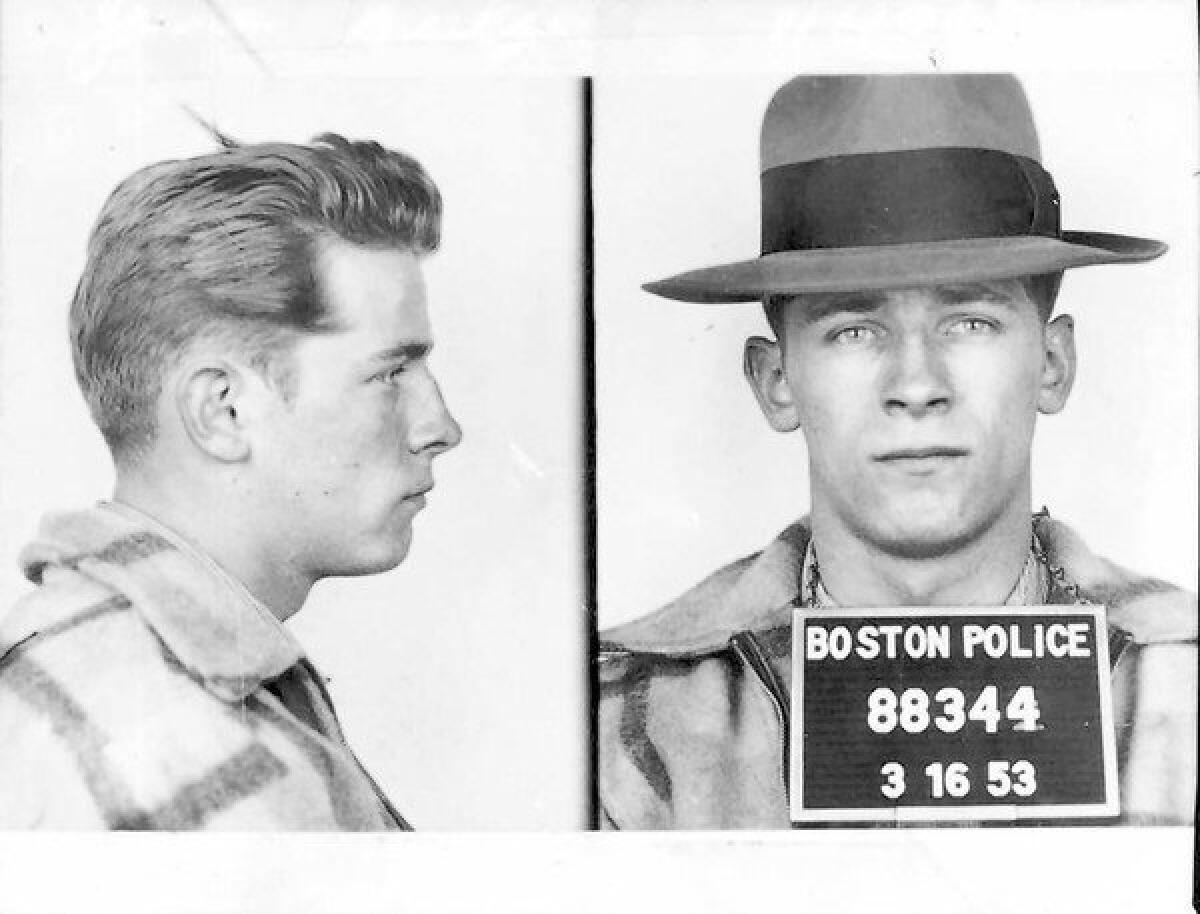

‘Whitey Bulger’ digs deep into a gangster’s tale

When Whitey Bulger was arrested in Santa Monica late on the afternoon of June 22, 2011, it brought to an end one of the longest, and strangest, manhunts in U.S. history. Nearly 82, Bulger had spent 15 years hiding in plain sight in an apartment complex near the Pacific with longtime girlfriend Cathy Greig.

In that time, he had literally reinvented himself: from a ruthless murderer and extortionist, who for more than a quarter century ruled South Boston, or Southie, to a grandfatherly figure, white-haired, bearded and nondescript.

“We were looking for a gangster, and that was part of the problem,” explains former Boston police detective Charles Fleming in Kevin Cullen and Shelley Murphy’s “Whitey Bulger: America’s Most Wanted Gangster and the Manhunt That Brought Him to Justice,” a definitive account of Bulger’s life and the city that helped create him. “He wasn’t a gangster anymore.”

That’s true, of course, although there is more to the story, since Bulger was nothing if not contradictory. How the man who inspired Jack Nicholson’s brutal mob boss Frank Costello in the Martin Scorsese film “The Departed” could simply walk away from a life of crime is an open question, but Bulger offers up a hint.

“She did what all the cops, prisons and courts couldn’t,” he wrote of Greig after his arrest. “Got me to live crime free for 16 years — for this they should give her a medal.”

“Whitey Bulger” is a portrait of its subject in all his complexity: devoted son and brother, vicious killer, neighborhood folk hero, anti-integration activist. (In 1975, he firebombed John F. Kennedy’s birthplace in Brookline, Mass., to protest Sen. Edward M. Kennedy’s support for enforced school busing, spray-painting the sidewalk in front of the house with the slogan “Bus Teddy.”)

It’s a terrific book — comprehensive, deeply reported, invested with an understanding of place and character, and the subtle, at times pernicious, ways they interact. This is hardly surprising; the authors, Polk Award-winning Boston Globe reporters (Cullen also has a Pulitzer), have been on the Bulger trail for nearly 30 years. Their expertise infuses “Whitey Bulger” with authority, a depth and an engagement that makes it less a work of true crime than a social history.

“[I]n his own bloody way,” Cullen and Murphy write, “Whitey Bulger’s life was fused with the modern history of the city. During his career he became one of its most recognizable icons. Boston is the city of John Adams, John Kennedy, and Ted Williams, but there are few names better known or more deeply associated with the city than Bulger’s. Certainly he is Boston’s most infamous criminal.”

That idea, of Boston as a city in which patrician elements are juxtaposed against a strong and rambunctious working class, resides at the heart of Cullen and Murphy’s investigation. And yet, as their book reveals, such borders are more fluid than they seem.

Bulger — who moved to South Boston in 1938 when he was 8, and grew up in public housing — may have learned that “[b]eing tough meant something in all of Southie, but especially the projects,” but his younger brother Bill went in a different direction, serving for many years as president of the Massachusetts State Senate and later president of the University of Massachusetts. The same was true of Bulger’s partner-in-crime Steve Flemmi, whose brother Michael was a Boston cop.

This porousness makes it difficult to establish clear lines between good and bad guys, to define, in any fixed way, right and wrong. Instead, as Cullen and Murphy make clear, everyone is complicit, from Bulger, who “considered himself more paternal than pathological, nothing like the other bad guys,” to “[t]wo accomplished men [who] assisted in this preening self-portrait: Bill Bulger, who could never fully face what a menace his brother was, and one of Bill’s protégés, FBI agent John Connolly.”

Connolly, as it turns out, became a central figure in the story, Bulger’s FBI minder, who “cast Whitey as an indispensible ally in the FBI’s war against the Mafia.” Yes, that’s right, ally; throughout his years in Boston’s underworld, Bulger was also an FBI informant, which allowed him a freedom, an immunity, he wouldn’t otherwise have had.

This might be the most disturbing element of “Whitey Bulger,” not because there ought to be honor among thieves but because it effectively removes any moral compass from the tale.

According to Cullen and Murphy, Bulger and Flemmi, despite having killed as many as 40 people, were not only protected but abetted by agents such as Connolly and his supervisor John Morris, who alerted them to threats and accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes and gifts. Connolly came from Southie and had looked up to Bulger as a child. The implication is chilling: that the bonds of neighborhood, of community, are stronger than those of ethics or legality, that in a city as insular as Boston, where you grow up trumps everything.

In that sense, Cullen and Murphy suggest, Bulger is a product of the streets he came from, although those streets are no longer what they were. “Southie was 98 percent white in 1970,” they write; “by 2000 it was 84 percent white, and by 2010 it was 79 percent white.”

Such changes echo shifts in the larger city, where “[t]he ethnic neighborhoods that had been home to the most prominent of the city’s organized crime groups — the Irish in Southie and Charlestown, the Italians in the North End — were gentrified throughout the 1980s and especially the 1990s.” Pointedly, they add: “If people wanted to gamble, they did so legally. The bookies were gone, replaced by state lottery machines.”

This is the final irony, that for all the torment Bulger caused, the state has provoked issues of its own. Cullen and Murphy make that explicit late in the book when they detail a run of wrongful death suits against the government by the families of Bulger’s victims, suits that were largely set aside.

“They talk about how arrogant Whitey Bulger was, how arrogant John Connolly was, how arrogant John Morris was?” says Tommy Donahue, whose father was killed in 1982 by Bulger, acting on a tip from Connolly. “What could be more arrogant than the FBI and the Justice Department never having the decency to apologize to my family?”

Whitey Bulger

America’s Most Wanted Gangster and the Manhunt That Brought Him to Justice

Kevin Cullen and Shelley Murphy

W.W. Norton: 496 pp., $26.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.