Hearst’s Mount Vernon West

A big splash. That’s what media mogul William Randolph Hearst made when he finished his Santa Monica beach house in 1931. Its gilded rooms and swimming pools impressed the neighbors, but Hearst had it built to impress the nation.

From the end of the Civil War through a Depression caused by speculator greed, America turned to its Colonial past for guidance. The Founding Fathers had survived battles and economic busts. They had founded democratic institutions for the public good and built sturdy white houses that were model American homes.

George and Martha Washington’s Mount Vernon stood proudly on the banks of the Potomac River. A women’s organization had saved it as a symbol of our endurance. To broadcast their faith in the American way, Hearst and his generation built modern Mount Vernons of their own.

Hearst was heir to a Californian mining fortune and the son of Phoebe Hearst, the first regent from California on Mount Vernon’s managing board. Her Harvard-educated son assembled a publishing empire that included Harper’s Bazaar, Cosmopolitan and the Los Angeles Examiner.

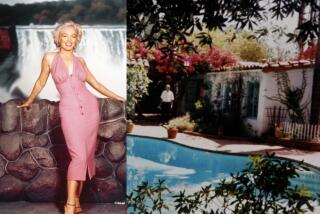

Known as the Chief, Hearst lived large until his death in 1951. He was married with kids. His girlfriend was actress Marion Davies. Together, Hearst and his star entertained Hollywood and Washington at the San Simeon castle designed by California architect Julia Morgan. Davies had a house in Beverly Hills, but Hearst wanted a place at the beach.

In 1926, he began construction at 415 Ocean Front, today’s Pacific Coast Highway. His powerful neighbors included producer Irving Thalberg, studio head Jack Warner and movie star Harold Lloyd.

At the time, Hearst had considered a run for president and was championing isolationists who argued against the League of Nations and entanglements with foreign governments. America had fought hard for independence, so why go meddling in the affairs of other countries?

These nationalist sentiments influenced Hearst as he guided his architects, set designer William E. Flannery and Morgan.

The Chief’s house faced the Pacific on a 750-foot stretch of oceanfront land. It had palatial rooms decorated with imported fireplaces, English antiques and portraits of Davies in leading roles. The decoration was good taste; the architecture was good politics.

A curved drive from the highway led to a semicircular porch that had a White House South Portico feeling. The front door opened to a double staircase inspired by the stairs at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, where colonists had adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

The ocean side of the house had 18 columns supporting a two-story porch. On the roof were windowed cupolas. The swimming pool, parallel to the house, was more Olympian than Virginian. Hearst adjusted its length several times and installed an arching bridge. He built a second pool in front of Morgan’s guest house along the estate’s western boundary.

A publicity innovator, Hearst used photo spreads to promote his agenda. Oceanside parties were effective propaganda. In July 1938, he celebrated his 75th birthday at the house. The theme was all-American. Celebrity guests arrived decked out as generals, Southern belles and Native Americans. On the oceanfront porch, draped with patriotic red, white and blue bunting, Hearst welcomed faithful Hearstlings. He was dressed as James Madison, the nation’s fourth president and an advocate of individual rights. The evening was a hail to the Chief at Mount Vernon West.

Hearst and Davies partied in Santa Monica in the 1940sand then sold their colonial manor to a developer. It became the Ocean House Hotel before being razed in 1956. The guest house and main swimming pool survived demolition.

This July 4, the nation is back at war and coping with economic collapse after more Wall Street excess. Once again the old Hearst property reflects the national tenor. Largely funded by TV Guide heiress Wallis Annenberg’s Annenberg Foundation, the city of Santa Monica has restored the Morgan building and pool as part of a public beach complex wedged into millionaire’s row. Where the Hearst-Davies house stood is a concrete, modernist pavilion designed by the L.A. firm Frederick Fisher and Partners. A white colonnade along the beachfront is a ghostly reminder of a time when George Washington’s Mount Vernon stood for the American dream.

For Watters’ past columns on L.A.’s lost homes and gardens, go to latimes.com/lostla. Send comments to home@latimes.com.