Smallpox stockpile could be destroyed; a look at what the virus wrought

International health officials are expected to decide this week whether to hold on to the last remaining stockpiles of smallpox, one of the deadliest diseases in history – or to proceed with their destruction.

The U.S. argues that scientists need access to the virus for just a while longer -- saying they need more time to develop antiviral drugs and vaccines in preparation for a potential terrorist attack that everyone hopes never comes. The Wall Street Journal explains the U.S. position, while also pointing out that other countries are convinced the risk of an accidental release isn’t worth taking.

At stake in the discussion – taking place at an annual meeting of the World Health Organization – are stockpiles at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta and at a Russian government laboratory.

As international health officials ponder the future of a still-terrifying virus, the rest of us might want to ponder its history.

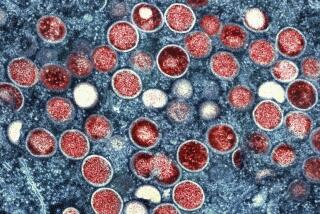

Smallpox, caused by the variola virus, infected – and killed -- people for thousands of years, as the World Health Organization reports:

“For centuries, repeated epidemics swept across continents, decimating populations and changing the course of history.

“In some ancient cultures, smallpox was such a major killer of infants that custom forbade the naming of a newborn until the infant had caught the disease and proved it would survive.

“Smallpox killed Queen Mary II of England, Emperor Joseph I of Austria, King Luis I of Spain, Czar Peter II of Russia, Queen Ulrika Elenora of Sweden and King Louis XV of France.”

The disease left many survivors blind or pockmarked. According to a Q&A on the disease from the CDC:

“The symptoms of smallpox begin with high fever, head and body aches and sometimes vomiting. A rash follows that spreads and progresses to raised bumps and pus-filled blisters that crust, scab, and fall off after about three weeks, leaving a pitted scar.”

Smallpox was fatal in up to 30% cases. In the 18th century, about one in 10 children in Sweden and France died of smallpox, according to the World Health Organization.

The development of the smallpox vaccine changed the tide. After hearing folklore that milkmaids who had contracted cowpox wouldn’t get smallpox, English surgeon Edward Jenner” href=”https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1200696/” target=”_blank”>Edward Jenner inoculated a boy with cowpox in 1796. Months later, Jenner demonstrated the boy was immune to smallpox (though others before Jenner had also discovered vaccination). News of the vaccine, and the vaccine itself, quickly spread through England, Europe and the United States.

The last U.S. case of smallpox was in 1949, according to the CDC, but some 50 million smallpox cases still occurred worldwide each year in the early 1950’s, according to the World Health Organization, which launched a plan in 1967 a plan to eradicate the disease. The last natural case in the world was in Somalia in 1977, and one last case—fatal—was contracted in a laboratory in the U.K. in 1978. The disease was declared eradicated in 1980.

Still, the U.S. holds onto the virus. The CDC explains in an emergency preparedness Q&A:

“In the aftermath of the events of September and October, 2001, the U.S. government is taking precautions to be ready to deal with a bioterrorist attack using smallpox as a weapon.”

The CDC even outlines its response plan—including how to use the remaining stockpiles to vaccinate the country’s population.

healthkey@tribune.com

RELATED: More news from HealthKey