Activists wield bolt cutters in a tense L.A. neighborhood as poor families seize empty homes

Weary after months of sleeping on other peoples’ couches, Martha Escudero walked through the broken door of an empty home in El Sereno and started bringing it back to life.

She fixed the garbage disposal, turned the garage into a classroom for her 11- and 8-year-old daughters and harvested squash and sweet potatoes from a vegetable garden she planted.

Her homesteading, part of an organized effort by tenant activists in March, was illegal, but it worked. The L.A. Housing Authority this fall granted occupancy rights to the family of Escudero and others who had seized numerous homes that the state acquired as part of now-abandoned plans to extend the 710 Freeway.

“I feel like it was the best decision of my life,” said Escudero, 41, who works as a caregiver for seniors. “Everyone deserves this.”

Other families agree and are willing to trample the legal niceties. Aided by activists armed with bolt cutters and drills, some have descended again and again on vacant homes in El Sereno, most notably on the day before Thanksgiving when clashes erupted between California Highway Patrol officers and people trying to take 19 more houses.

These days an uneasy calm hangs over the community. Some residents have confronted the activists and hung signs outside their homes saying, “Squatting is not the answer.” Would-be occupiers, meanwhile, continue eyeing the houses, which are owned by the California Department of Transportation. Police and private security stand guard in driveways, ready to drive them off.

“The first time around it was very shocking,” said Marie Salas, who lives across the street from the house Escudero occupied. “But the audacity, the carelessness, the I-don’t-care attitude about the neighborhood to say, ‘We’re going to break in again?’ It’s just disgraceful.”

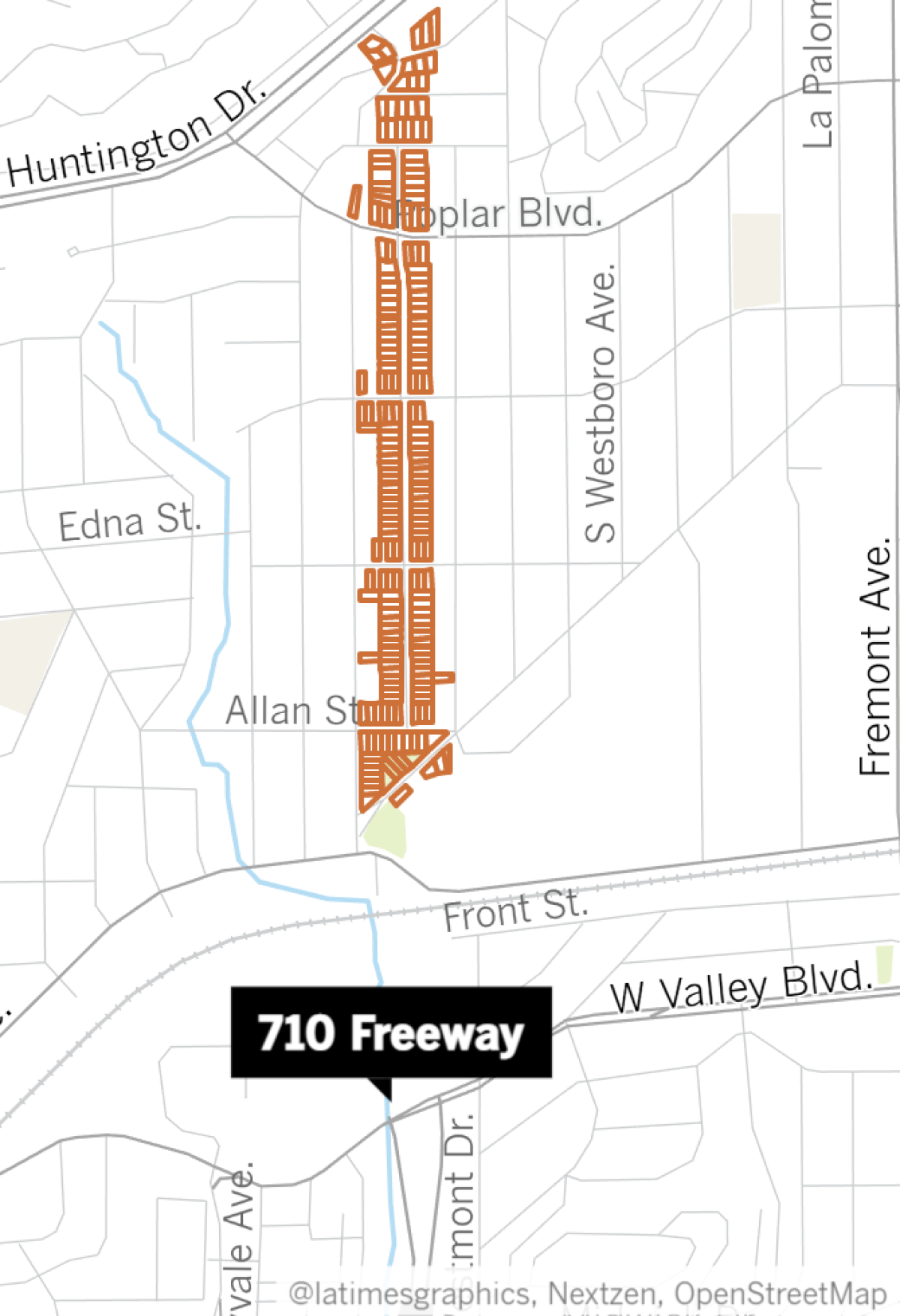

The story of how the state transportation agency came to own over 400 properties — including more than 80 now-vacant single-family homes — is decades old and newly urgent. Caltrans began acquiring the properties in El Sereno, Pasadena and South Pasadena in the 1960s as part of efforts to expand the 710 Freeway, but protests and lawsuits delayed the project and it was officially killed two years ago.

Caltrans now holds a real estate portfolio of modest bungalows, Craftsman mansions and, most famously, the Pasadena childhood home of chef Julia Child, which has been empty for 35 years.

While Caltrans has rented out homes for some time — Salas has been a Caltrans tenant since 1997 — the agency has let many deteriorate.

But the dilapidated conditions are no deterrent to families pummeled by the once-in-a-century global health pandemic and housing affordability crisis.

The spark for the El Sereno takeovers actually came from Northern California, where a group of impoverished Black mothers in November 2019 seized a vacant corporate-owned home in Oakland. The occupation, done with the help of a statewide tenants group, made national news. Public pressure led Gov. Gavin Newsom to help broker a deal to sell the house to a community-led organization.

El Sereno activists, also assisted by the tenants group, the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment, mounted 13 home seizures in March, just as government officials issued their first pandemic stay-at-home orders. To leave Escudero less vulnerable to arrest, supporters — Escudero says she doesn’t know exactly who — broke into the house beforehand so she could just walk inside without incident.

Caltrans allowed those who seized the homes to stay. The effort ultimately led to the Los Angeles housing authority agreeing to lease 25 homes for use as temporary housing. Eight families, including Escudero’s, are living in the homes now; the others are being repaired. Escudero began paying rent this month.

As for the remaining vacant homes and apartments, which number at least 120, there’s little indication they’ll be filled any time soon.

Agency officials say these properties, which suffer from electrical, flooring and plumbing problems, are unsafe and uninhabitable. And Caltrans must comply with a lengthy and complicated legal process to sell them, with former owners and current tenants given the first chance to buy. Only 10 have been sold thus far. State legislation aimed at speeding the sales failed earlier this year.

Why Caltrans decided not to remove those illegally occupying homes in March isn’t clear, but some people interpreted the move as a green light.

One day in early August, an unemployed hair stylist decided she had waited long enough.

With the help of some friends who jimmied the back door, Sasha Atkins, 31, walked into an empty home in El Sereno with plans to stay.

Atkins was inspired by the initial occupations. She’d been staying in motels with her 9-year-old son for a few months after losing her job. Pandemic health fears had limited her ability to double up with friends and family, as she had been doing over the past three years.

After five hours in the Caltrans house, police found Atkins and she left the property.

She tried again the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, picking a lock to force her way into a duplex. She spent the night but left the next afternoon as officers prepared to enter the building.

She said the daily pressures of trying to keep a roof over her head made her do something she otherwise wouldn’t.

“I have to stress on educating my kid. I have to stress on where my kid’s going to sleep. If we had a home, it’d be so different,” Atkins said.

Multiple activist groups have organized the mass home seizures, adding to the confusion as neighbors worry about unknown outsiders descending on their community and government officials struggle to determine with whom to negotiate. In March, those behind the occupations called themselves Reclaiming Our Homes. A separate group called Reclaim and Rebuild Our Community emerged later and arranged the attempted takeovers over Thanksgiving.

Unlike Atkins, others who occupied houses over Thanksgiving didn’t leave so peacefully. Videos showed police, clad in riot gear, using battering rams to enter properties and handcuff and drag out the occupants as crowds spilled into the streets. By Thanksgiving night, more than 60 people had been arrested, officers said.

Neighbors in the community of well-maintained properties in the $675,000 range express mixed feelings about the escalating tension. Some support the effort to sell or rent the homes to needy families, but strongly oppose the methods of the families and their activist allies.

After hanging a banner protesting the home seizures on her fence, Salas said she has had rocks and empty beer cans thrown in her frontyard. Another neighbor, Aaron Mauricio, said drill-wielding activists shoved him while he was trying to stop them from getting inside a vacant home on his street.

“There’s families here. There’s kids here. They were breaking the law and they had no right to do what they were doing,” said Mauricio, 48, a middle-school teacher.

Some in the community question whether the people seizing the homes truly need them the most. Maria Elena Durazo, a Democratic state senator who represents the area, said everyone arrested as part of the Thanksgiving protests gave police a permanent address, and that occupiers declined hotel room vouchers that would have provided immediate shelter.

“The particulars here were not about homeless people wanting a place to stay,” Durazo said.

Atkins bristled at the suggestion that her years of bouncing between friends and family’s homes and motels meant she didn’t need a permanent place to live.

“Right now, I’m sitting outside of a motel with my son who is doing his homework,” she said. “I am homeless.”

For now, Caltrans has once again boarded up the vacant homes after the attempted Thanksgiving occupations. While Durazo has introduced a new state bill to speed property sales, it wouldn’t require the transportation agency to act until mid-2022.

Activists, meanwhile, are adopting more subtle ways to keep up the pressure. They have raised more than $58,000 as of Tuesday in support of their efforts. And on Monday night, a bouquet of flowers alight with Christmas ornaments appeared in front of vacant homes. In a tweet, Reclaim and Rebuild Our Community said the flowers were an “offering” for the homes they could be living in over the holidays.

Atkins isn’t sure if activists will try to seize more properties. But she’s ready.

“If someone was to say, ‘Let’s try again,’” Atkins said, “my bag’s already packed.”

Times staff writers Laura J. Nelson and Sarah Parvini contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.