From Donna Summer to Tupac Shakur, Sunset Boulevard is the backdrop to a history of classic songs

- Share via

Music man Lou Adler lives a few miles north of the intersection of Sunset Boulevard and Pacific Coast Highway, where, on a recent afternoon, an anonymous musician had plugged his red Fender electric guitar into an amp and was jamming for cash as cars waited at the stoplight.

The ax-man could have been mistaken as a hired hand placed there for effect to mark the spot where one of the most consequential music boulevards in America ends at the beach.

For the record:

10:35 a.m. Aug. 25, 2017An earlier version of this story identified an Elliott Smith-themed business as being a coffee shop. It is a restaurant.

Raised in Boyle Heights, Adler, 83, has been a prime mover in the L.A. music business for nearly 60 years. He had welcomed a request to talk about his musical life while rolling up and down Sunset.

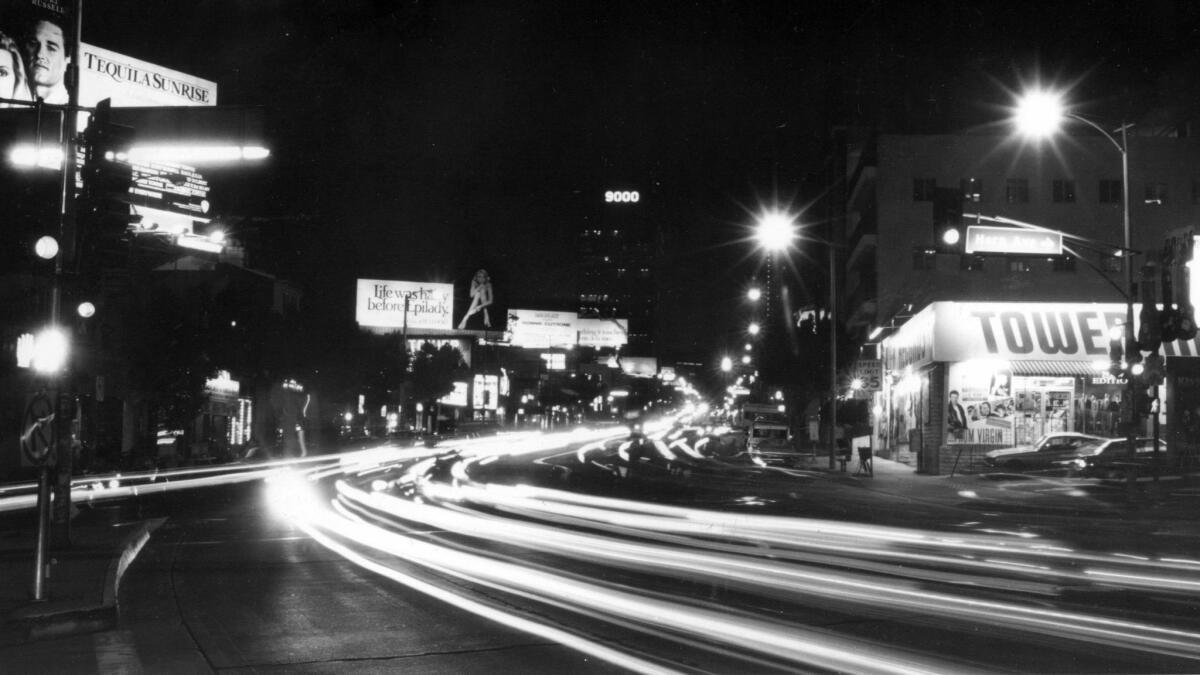

The boulevard, first recorded as Sunset in 1888, is indexed in virtually every book about Los Angeles and music, and is mentioned in hundreds of songs by artists — Steely Dan, Tupac Shakur, Donna Summer, Grant Lee Buffalo, to name but a few. It’s a symbol for a certain kind of sun-drenched spirit.

FULL COVERAGE: Mapping Sunset Boulevard’s musical history »

Given the proper guidance, it’s possible to glide westbound along Sunset’s 22 miles from downtown Los Angeles to the beach without once using your blinker and cruise past musical sites that have helped define pop culture.

“Drive west on Sunset to the sea,” sings Donald Fagan to open the Steely Dan song “Babylon Sisters.”

When Shakur raps on “To Live and Die in L.A.” that he’d “learn[ed] how to think ahead so I fight with my pen,” he jumps across town from Crenshaw Boulevard and MLK Boulevard to a “late night on Sunset.”

Adler started out as a song hustler and now owns a compound on the bluffs overlooking the ocean, evidence of a lifetime of success in the entertainment business that includes being a record producer/label head, film producer, festival promoter and club owner.

After relaying a few stories about his life marketing songs along Sunset, working in the publishing business and co-owning the historic music club the Roxy, as well as the Rainbow Bar and Grill, Adler pauses. Dressed in all-white casual, white Crocs and a flat hat turned backward, he looks every bit the king of something.

“As I’m talking, I didn’t realize just how much Sunset Boulevard has meant to me,” he says.

“A&M, which I eventually had Ode Records at, was right off Sunset Boulevard on La Brea. The first time I heard ‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand’ by the Beatles, I’ll never forget how much I thought, ‘Wow, this is it!’ Yeah, it was on Sunset.”

The first time I heard ‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand’ by the Beatles, I’ll never forget how much I thought, ‘Wow, this is it!’ Yeah, it was on Sunset.

— Lou Adler

The office where he helped launch the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967? That was on Sunset too, as was the first U.S. stage production of “The Rocky Horror Show,” the film adaptation of which Adler produced. So are the Roxy and the Rainbow, both of which he played a key role in opening.

Adler’s not the only one who has been shaped by Sunset’s vibrations. This town may be a gloriously sprawling mess of scenes and sounds, but for decades the boulevard has held some of the country’s most important music-related addresses.

“A constant stream of singers, musicians, friends and family flowed in and out of the recording studios along Sunset,” writes Carole King in her autobiography, “A Natural Woman.”

Since at least the 1940s, Sunset has held recording studios, record shops, rehearsal spaces, musical instrument stores, agents, publishing companies, clubs and record labels.

“It lays out in this brilliant way,” says filmmaker and longtime Los Angeles music insider Allison Anders, suggesting a guided tour would be “quite a nice music walk — and along the way you’d have the history of movies and and TV too.”

But for all its renown, Sunset has hit dusk when it comes to music. As with Whittier Boulevard and Central Avenue, both of which in their prime were music hubs, the era when a single road could define an ideal seems to be vanishing in the rearview mirror.

The boulevard’s record label scene is all but dead, having never recovered from a series of late-’90s layoffs that saw scores of former employees exiting offices and walking down Sunset with their boxes. The most prominent new players on the boulevard are media companies BuzzFeed and Netflix.

In May, the longtime Strip fixture Mario Maglieri, who co-owned the Whisky a Go Go and Rainbow Bar and Grill and managed the Roxy, died. Earlier this year the wrecking ball visited the House of Blues. Earlier this month a building proposal for the land currently occupied by Amoeba Music in Hollywood prompted renewed speculation that its days on Sunset are numbered.

The Silver Lake spot where Elliott Smith posed for the cover of “Figure 8” is now a Smith-themed restaurant. Any band that throws a TV out of a window at the hotel formerly known as the Riot Hyatt on the Strip — now the Andaz West Hollywood — would likely be arrested.

Lyrically speaking, contemporary Los Angeles has relocated south, where it runs to the rhythm of Kendrick Lamar, Snoop Dog and Dr. Dre’s Rosecrans Boulevard.

As it wends through various income brackets and hipster hoods downtown, through Echo Park, Silver Lake, Los Feliz, Hollywood, West Hollywood, Beverly Hills — watch out for Jan & Dean’s “Dead Man’s Curve” — Bel-Air and Pacific Palisades before washing into the surf just across Pacific Coast Highway, Sunset manifests a grand story about popular music and Los Angeles.

“It’s invisible now, but if you know it, you’ll still feel it,” Anders says.

For tips, records, snapshots and stories on Los Angeles music culture, follow Randall Roberts on Twitter and Instagram: @liledit. Email: randall.roberts@latimes.com.

ALSO:

Sunset Stories: Musicians ponder the power of L.A.’s musical boulevard

Music-making memories of Sunset Boulevard, from the Beach Boys to Vince Staples

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.