The rise and fall of a Sons of Iraq warrior

AMMAN, JORDAN — A year ago, Sunni Arab fighter Abu Abed led an improbable revolt against Al Qaeda in Iraq. As he killed its leaders and burned down hide-outs, he became a symbol of a new group called the Sons of Iraq -- the man who dared to stand up to the extremists in Baghdad when it still ranked as a suicidal act.

Today, Abu Abed is chain-smoking cigarettes in Amman, betrayed by his best friend, on the run from a murder investigation in his homeland. He once walked the streets of Baghdad wearing wraparound sunglasses and surrounded by a posse of men in matching fatigues like something out of “Reservoir Dogs,” but now he shouts futilely for speeding taxis to halt, a slight figure in jeans and a button-down short-sleeve shirt.

Abu Abed’s rise and fall encapsulates the complexities of the U.S.-funded Sons of Iraq program. Although the Shiite-led Iraqi government has regarded the Sons of Iraq as little more than a front for insurgent groups, the Sunni fighters’ war helped end the cycle of car bombings and reprisal killings by Shiite militias that had sent Baghdad headlong into civil war. America’s new friends also helped bring down the death rate of U.S. forces in Iraq.

The Defense Department’s report to Congress last week emphasized the vital nature of the program, saying, “The emergence of the Sons of Iraq to help secure local communities has been one of the most significant developments in the past 18 months in Iraq.”

Abu Abed’s flight into exile shines a light on a violent power struggle pitting upstart leaders like him against Iraq’s entrenched Sunni political elite and its Shiite-dominated government. The frictions could easily shatter the Sons of Iraq -- and open the door to Al Qaeda in Iraq’s resurgence.

Perhaps even more significantly, the charges against him belie the notion of an Iraqi government moving toward reconciliation among its Sunni and Shiite populations.

The man who served as Abu Abed’s U.S. advisor until January expressed complete confidence in the fighter. “Many times he had the opportunity to do the wrong thing and never did,” said Eric Cosper, a retired U.S. Army captain. “I have absolute faith in him.”

Medals and memories

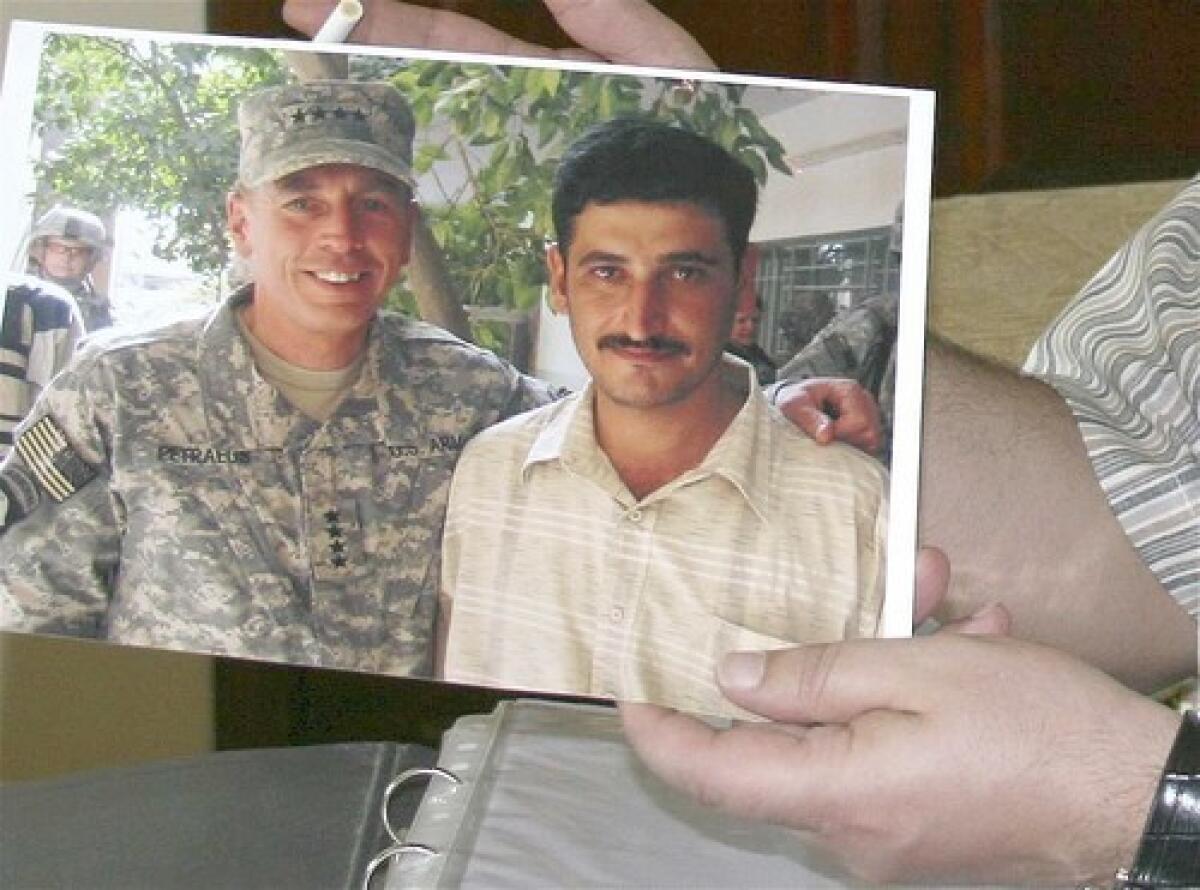

In the cramped Amman apartment he shares with his family, Abu Abed opens a folder with pictures of him and American officials -- Army Gen. David H. Petraeus and others. He holds up the medals they awarded him, the letters commending him.

But his eyes glaze over at a photo of Iraqi officials from a reconciliation conference he attended in mid-June. “They pat you on the back with one hand and stab you with the other,” he says bitingly.

Abu Abed doesn’t reveal his identity to people in Amman. He tells them he sells cars. His skin is grayer and his cheeks, once plump, are noticeably gaunt. The family has already moved once, after his 8-year-old son was handed a threatening letter at school.

He worries that his fate will serve as a warning to others who gambled their lives fighting Al Qaeda in Iraq. “Al Qaeda will come back and the government and Iraqi army will be helpless to defeat them. People will have lost their faith in the government because of the way they treated me and others.”

The government considers Abu Abed a former militant with blood on his hands.

“If he has done something, let the legal system take its course. It is not just with Abu Abed, but all the people,” said Tahseen Sheikhly, an Iraqi government spokesman for Baghdad military operations. “They were part of the major problem of violence in Iraq.”

Abu Abed’s defenders, including some U.S. military officers, suggest that the fighter earned enemies for upsetting Baghdad’s status quo as he brought former insurgents into an alliance with the Americans.

In recent months, Abu Abed had been organizing like-minded fighters around Baghdad and northern Iraq for provincial elections in the fall. U.S. officers believe his transition to politics could have proved the last straw for the government.

“Certainly you can draw the conclusion because he was getting involved in the political process to engage Sons of Iraq leaders to form a political party, the Iraqi government actively targeted him,” said a U.S. military officer, who declined to give his name because of the subject’s sensitivity. “I don’t know that I can say it outright, but it certainly does seem that way.”

Amid the political skirmishing, the committee set up to integrate U.S.-backed Sunni fighters into the security forces and public works jobs has stalled.

Iraqi officials have been cryptic about the reason. Sheikhly acknowledged that the committee’s efforts had slowed to a crawl, but said it was because the committee had shuffled members.

Others are more explicit. Sheik Fatih Kashif Ghitaa, a prominent Shiite who runs a think tank with close ties to the government, said Prime Minister Nouri Maliki had frozen the committee because of Shiite anger over America’s failure to act against fighters such as Abu Abed.

One Western official agreed that the government’s decision was deliberate.

“The coalition twisted Maliki’s arm on the committee,” the official said on condition of anonymity, referring to the prime minister’s decision to create the body last year. “And now he has decided, we don’t need it. As far as he is concerned, this is an American problem.”

A close call

The writing had been on the wall for Abu Abed since the end of April, when he stepped out of his vehicle on a quiet side street to attend the weekly council meeting in Amiriya, his Baghdad neighborhood. The normal guards weren’t outside.

An explosion threw him into the air. Shrapnel flew into his skull, face and chest and punctured his eardrum. In his Amman apartment, he whips out a picture of the suicide bomber’s charred leg.

In mid-May he arrived in Jordan for laser surgery. He planned to be away for a month. The government had invited him to attend a reconciliation conference in Sweden. Afterward, he would return home.

But in Sweden he learned that he was being investigated after the discovery of three corpses found buried in concrete in a house in Amiriya this month, the existence of an alleged execution room as well as the assassination of an Al Qaeda in Iraq member.

“This is political. They accuse me now of killing people and burying them. I am not taking any step outside of my office in Baghdad without 30 guards around me. These are false accusations,” Abu Abed said.

The Sunni fighter blamed the charges in part on long-simmering feuds with the Iraqi Islamic Party, the exiled Sunni group that came back after the 2003 invasion to dominate the sect’s politics until groups such as Abu Abed’s emerged.

For their part, Islamic Party members and supporters, speaking on condition of anonymity, depict him as a man who started out well but quickly became drunk on power and his ability to kill.

A top aide turns

Now that he is abroad, Abu Abed says, his enemies have moved quickly. An Iraqi army general, associated with the Islamic Party, ordered several raids against his properties in Baghdad, and Abu Abed’s younger brother was briefly detained by the general’s men before fleeing to Syria. But the deepest cut, he says, has been his betrayal by his top aide, Abu Ibrahim, who declared himself the new head of the Sons of Iraq in Amiriya.

He blames himself for trusting his friend too much. When they first started fighting Al Qaeda in Iraq a year ago, Abu Abed says Abu Ibrahim had abandoned him, leaving him to die in a mosque under siege with a handful of supporters. Afterward, when the battle was won, Abu Abed says, he forgave his friend and brought him back into the fold.

Every day, Abu Abed hears reports of how Abu Ibrahim has confiscated his weapons, clothes and motorcycles. He hears how his friends call him another Saddam Hussein.

His wife hands him an American flag and the red banner of the U.S. Army battalion he fought alongside in Baghdad. He opens them lovingly, and then refolds them, a remembrance of things past.

--

ned.parker@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.