- Share via

This story is part of Image Issue 14, “Elevation,” where we examine beauty as a state of being, a process of realization. Read the whole issue here.

The smog of mourning is thick, sometimes impossible to maneuver. So when Nate Dogg’s 1998 hit “Nobody Does It Better” empties from the speakers of a Lyft driving me north on Crenshaw, just two days after my grandmother’s funeral in August, I don’t immediately recognize it for what it is. I drift in and out of the notes, licorice-sweet, my mind wandering. Grief paralyzes — it weighs and rattles the mind, robs the senses of their natural logic. I forget that the song, very simply, is its own kind of prayer, a thing of unselfish beauty. Instead, I do what comes naturally. Under a blanket of blue sky, I ask for volume, more volume.

“Nobody Does It Better” is not Nate Dogg’s highest-charting release, but it remains, for me, his most celestial. It’s pure invocation. The key to its unlocking is all in Nate’s delivery, its controlled grace. Over a dreamy bed of keys, what was a masterly sample of Atlantic Starr’s 1982 slow-burn “Let’s Get Closer,” his satin-crisp baritone glides with unshowy self-possession. Like the most sterling of prayers, its first exhale is a passageway. It opens something up.

On the track, Nate sings about life as told in the rearview. Even then, at such an early juncture in his career, the song reads like a victory lap. My exhibition started back in ’93 / No one, nobody listenin’ but Warren and me / To all the nonbelievers, now I bet you see. Nate is patient and polished, careful not to overpower the beat, smooth as a pair of new Stacy Adamses. The tempo is unhurried and chilled but the feeling it gives is not: I am set alight. Something in me goes off.

Beauty unpins something deep within. To come into contact with it is to marvel at the nature of hope, and how it works. As I’ve matured into my 30s, I’ve tried to understand its many permutations. What I know is this: The great hope of beauty — because beauty always deals in possibility — is to awaken. Such awakenings are not always immense undertakings, though they can be. Beauty at its most refined is a subtle reminder. Beauty says, “I see you in me.”

The fact of Nate Dogg’s passing, in 2011 of heart failure, is suffused with crooked poetry. The music poured out of him, giving all of what he had, flowing into a world he knew all too well. When you lose someone like that, can that kind of hollowing out ever be filled? Is that kind of beauty possible again?

DJ Quik discusses legacy, L.A. music, Death Row records

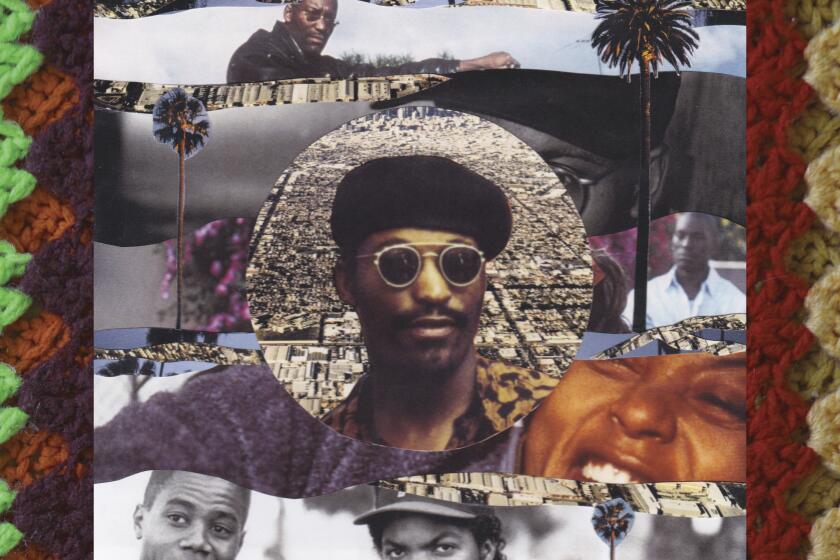

A soul barer and a tireless collaborator, Nate Dogg was the preeminent rap vocalist of the 1990s. He was raised in Long Beach in the tradition of our finest city-tellers — singing of the times that defined him, of the moments that made him. As the Smokey Robinson of hip-hop, he created a catalog that was defined by topographies: Across three solo albums and one joint record with his group 213, he mapped the wilderness of adulthood with a too-suave realism, graphing the fleeting thrills and terrors that came with being a Black man. He sang of a liberated Black romantic that diverged from social orthodoxy. Women and weed were often his cardinal texts.

Perhaps it all roots back to where he was raised. In many of his songs, there is a sense of caretaking, of admiration and respect for Long Beach, the city that molded him. It was an emphatic love that he carried for where he came from and what he believed others could find in its everyday lore, its domestic luxury and relatability.

If you grew up on SoCal radio anywhere between 1992 and 2004, a time of political turbulence and street fortune, Nate Dogg was a constant, the blunted bard of our blue summer days. On cuts like the 2Pac-assisted “Me and My Homies” and the melancholic “These Days,” he didn’t just give the ordinary meaning — he illuminated it with soul. He infused it with the kind of beauty that was surprising but inevitable. He decorated it in the tradition of the Black church and the boldness of rap, a bluesician with the instincts of a rare collector, making what was old new again.

By 1998, the year his solo album dropped, Nate Dogg had established himself as the reigning rap vocalist of the era, the embodiment and voice of the subgenre G-funk (naturally, the G stood for gangsta). So it was only appropriate that he christened his debut “G-Funk Classics, Vol. 1 & 2.” Outfitted with low-rider tough production and stabilized by his trademark syrup-thick vocals, the album outlines the spirit of the era in bold colors — its pleasure-seeking, its pathos.

“G-Funk Classics” was sheer sprawl. Totaling 31 songs and loaded with an all-star lineup of features that included Snoop Dogg, Daz Dillinger and Kurupt, Nate Dogg attempts to give legibility to the funk of life, detailing the horrors from which he and his boys arose and, in the end, the favor that would sustain them until their last days. He colored without embellishment.

The conflicted heart of Nate Dogg’s aesthetic project was about surviving a secular world with spiritual tools. His church upbringing was never far from his mind. One early-album cut — “First We Pray” — finds Nate summoning the grace he so deeply sought even as impossible realities befell him. First we pray, then we ride. The breezy refrain barely draws attention, but it was representative of the easy-to-miss beauty Nate made a hallmark of his career. It’s all there, between and beyond the layers: his vocal depth, the insistence on prayer for protection, the solidarity implied in his use of “we.” Coming from where Nate came, the funk of life was unabating. Banding together — sticking with and up for your people — was often the only remedy for survival.

More stories from Elevation

Rikkí Wright unpacks the beauty routine as a metaphor

Rembert Browne comes of age without a hairline

Devan Díaz takes on tweezing as self-care in our warped times

Dave Schilling investigates why the mullet is the haircut that refuses to die

The state of L.A. beauty in one zine

Of course, he survived until he couldn’t. He never fully escaped the jungle of adulthood, even as he sang about it with a knowing appreciation. The latter shades of his life were muddied by alcohol abuse, run-ins with the law, domestic quarrels and health issues.

I believe part of what makes beauty an object of collective want — what gives it allure — is its opposition, the ugliness on the other side. We covet beauty with abandon because the alternative is too nightmarish a thought. One gets the feeling that Nate Dogg chased the romance of life and the joy it afforded, a sometimes failed pursuit, because he knew just how ugly the other side was, and what was waiting for him there. He chose never to dress up his music, and the stories within, so much as greet them where they were. Converting the ordinary into the divine — that is what gave his music its holiness, its aura.

“I had the heart of rap but my style was to sing so that’s what I did,” Nate once said in an interview with Nina Bhadreshwar, recalling the motivation that fueled his early days. “What me and my homeboys are going through in life — that’s our reality, that’s what I sing about.”

The beauty, and irony, of Nate Dogg’s music was that the stories he told were sometimes not very beautiful at all. The academic Saidiya Hartman has said that beauty is “not a luxury” but instead “a way of creating possibility in the space of enclosure, a radical act of subsistence, an embrace of our terribleness, [and] a transfiguration of the given.” That was Nate’s gift, the glimmer of his music — from a place of enclosure, he embraced the ugliness, as well as the gratification, of our world.

From the jump, there was a naked awareness in his storytelling. He transformed the given into a thing of splendor. He made plain the storms of Black manhood even as he sailed through them. The 1994 single “One More Day,” his first as a solo artist, is about second chances and how scarce they were for Black men. A reality he was not unfamiliar with. On Warren G’s hood noir “Regulate,” released the same year, Nate trades bars with Warren, a kind of rap duet, recalling a story of retribution. Nate knew as much: The terribleness of the world could not be avoided, but it could be rendered with a gentleness.

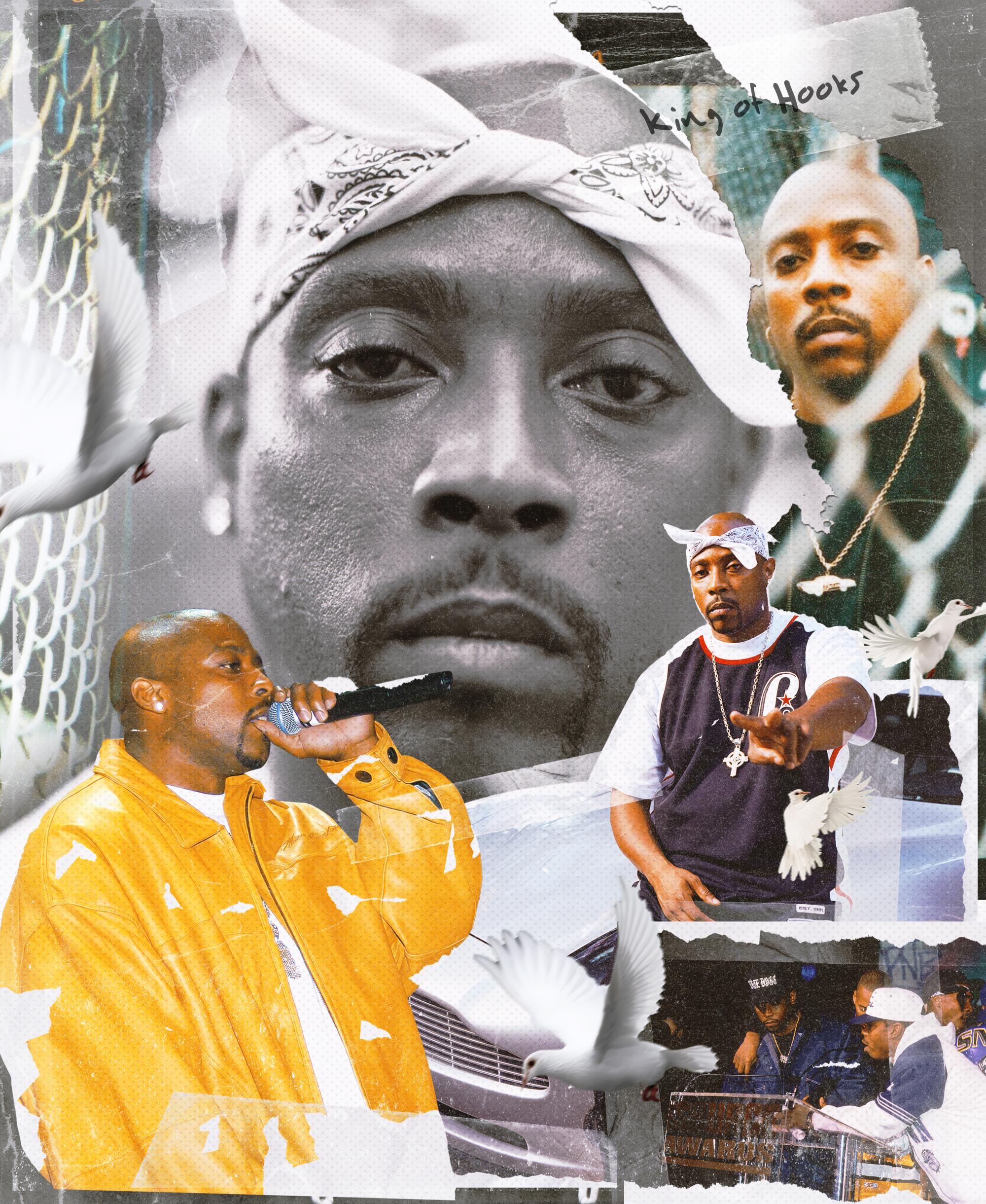

The filmmaker’s movies were hard and unflinching in their portrayal of Black Los Angeles but really what they are about is our fundamental human enterprise: the grace of feeling.

I have always believed it was that gentleness — steady, patient, assured — that influenced his music more than anything else, against the hard pragmatism of the era, during a moment when West Coast gangsta rap was defined by a poetics of fury. The cornerstone of the period was concerned with the durability of one’s exterior shell and shape. That particular hubris never completely left him. Nate Dogg was an unrelenting collaborator until his last breath, and many of his careerlong features convey that slick posturing, from Ludacris’ “Area Codes” to the bounce of Fabolous’ “Can’t Deny It.”

What the design of those songs fails to capture fully, however, is the duality of Nate’s vocation. Held within each of his songs, and the way he assembled them, was a particular chemistry. He presided over a unique middle terrain in rap songwriting where the punishing realities of what was being sung about were greeted with the compassion of the individual soul. Nate came up at a moment when the music industry was not so different from the roar and rumble of the Wild West during the early days of the American frontier, but he chose to confront it with a creative lightness. His voice was like a cradle, rocking the listener into a kind of submission as he buffed the edges of the stories foretold. The effect of his baritone was a deep marination. After all, everything goes down easier with a little seasoning. The purpose of his work, of what his voice bestowed, was unequivocal: Nate didn’t sing on tracks, he straight-up blessed them.

Where one begins and ends with Nate Dogg is the engine of his creativity, his voice. The architecture of it was no simple thing. Waiting to be set free over a hammering beat was a stratum of harmonies. Listening to him is a reminder: Beauty is not merely a visual practice; it is also, and perhaps more powerfully, an audible one.

Before Auto-Tune became a trendy requirement for chart dominance, Nate sang with a serene swagger. His was an unmistakable gentleness. All lungs and heart, his vocal range stretched from B♭1 (best distilled on Eminem’s “Never Enough”) to E5 (213’s “My Dirty Ho”). But it was in C4, hovering where he did so often over a beat from Dre or Daz, where the beauty of his singing was at its most intoxicating. Entering the final two minutes of Mista Grimm’s perennial 1993 bop “Indo Smoke,” Nate repeats the phrase — Are you high yet? — and builds on it with each repetition, elongating the words like fresh cursive, curling them just so. His pitch is controlled but gives the effect of a swell, the way a classic choir hymn does. The notes are like small crowns in his ever-expanding kingdom of harmony, each one more entrancing than the last.

Producers, promoters musicians, artists, DJs and others share their favorite L.A. party anthems, plus the memories surrounding them and their thoughts on what makes a party hit.

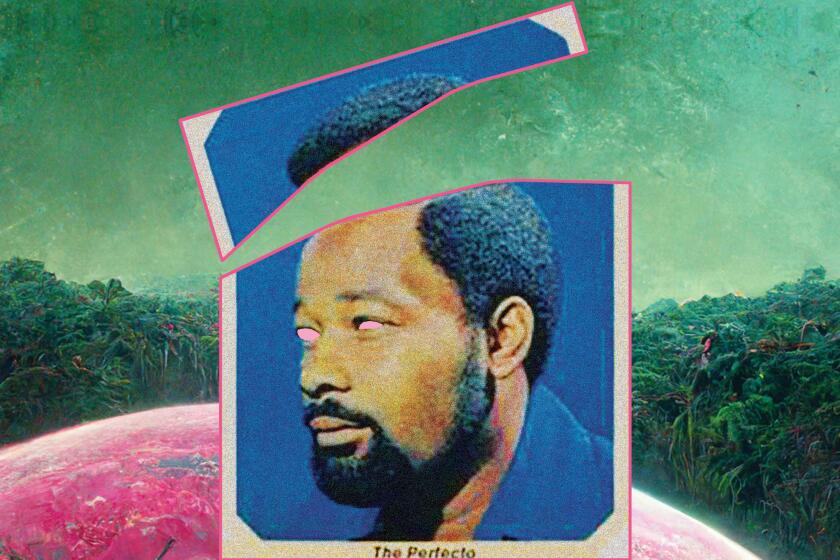

Like our greatest practitioners of the form, Aretha and Marvin and Whitney and so on, Nate’s voice was a bridge, scrubbing away the pain of life and making room for its simple sweetness. Because to render beauty audibly is to commune with a higher power, it is to understand life, its storms and sunrises, in a sacred way.

“It’s just me. I give them my music, and hopefully my music will explain who I am to people,” he said in an interview with Yahoo in 2001. “It’s like a releasing point. Without my music, there would be no me.”

That was the ultimate draw of Nate’s talent. A consummate hook man, he found a way to wrest comfort from hardship — has Smoke weed every day ever sounded so godly? — and perhaps, in the end, that’s what it was all about, stripping life of its artifice, removing the varnish that blinds us from what really matters. The pursuit of one’s purpose. The adrenaline of love. Family and friends, those here and those gone. More than the pure majesty of his voice, that was beauty for Nate Dogg. He discovered how to call it his own. He discovered how to name it. He saw it just as it was.

Jason Parham is a senior writer at Wired and a regular contributor to Image.

More stories from Image