I grew up knowing that anything you create that becomes too famous is no longer yours, even your father and especially his music.

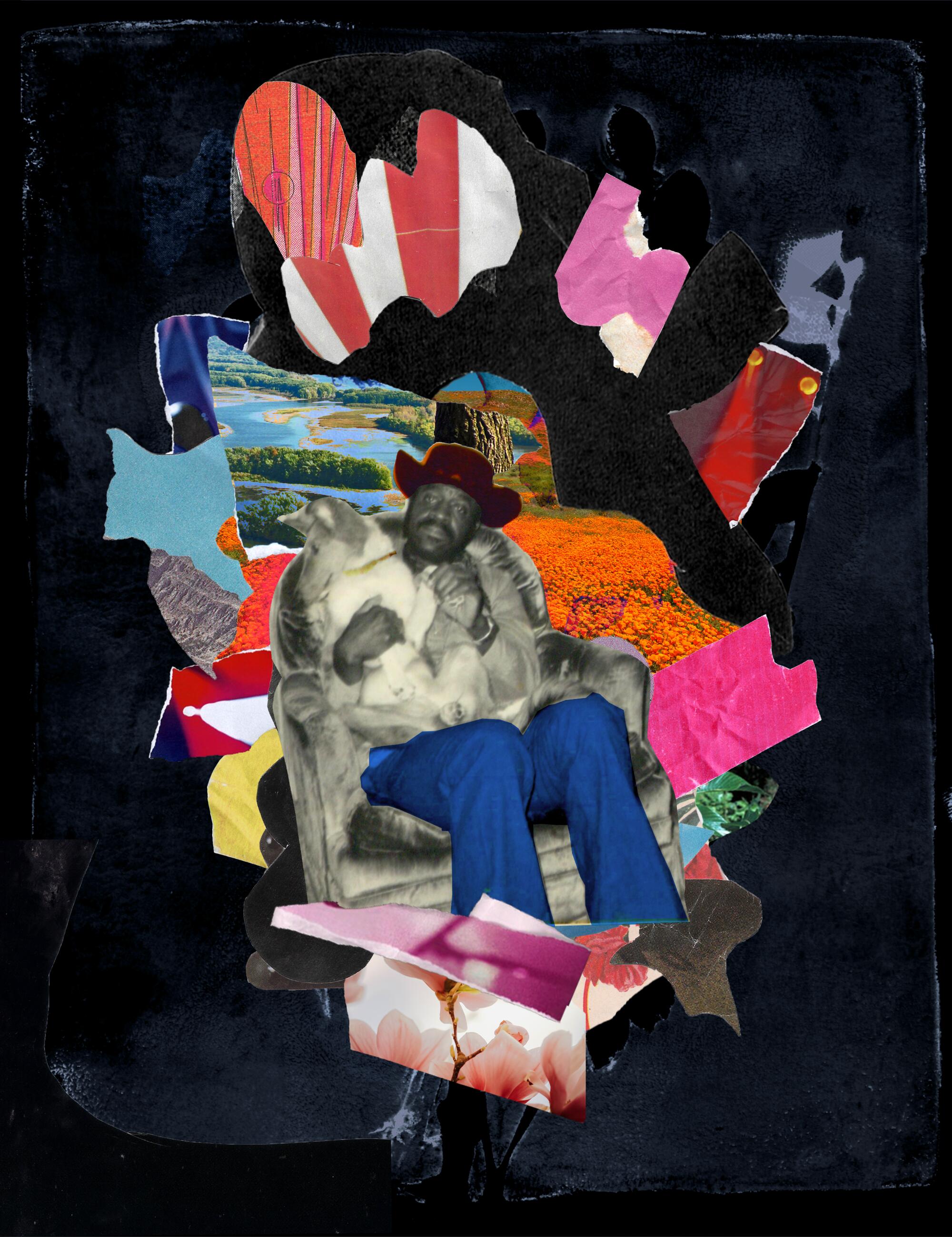

Jimmy Holiday was a Black cowboy-musician who migrated from the Mississippi Delta to New Orleans to Hollywood in the late 1950s. He was also my father. At the time he moved to Hollywood, it was one of the few coastal destinations that promised Southern Black sharecroppers like him, one generation away from chattel slavery, a chance at the so-called American dream they had been sold on the radio. Had it not been cast as a land of second chances in a state with an idyllic climate, Hollywood may have remained a splendid desolation of abandoned studio lots. Instead, it became home to those who were brave enough to audition for leading roles in their long-harbored fantasies.

Jimmy moved from place to place in the style of an unapologetic and relentless fugitive, trying to escape what he knew in order to do justice by it. There are lost years between his upbringing as a sharecropper in the Delta and his arrival at Ray Charles Enterprises in Los Angeles, and I invade those years with a remix of his own music and the Technicolor acoustics of films from the ’50s and ’60s, which is to say I occupy that absence with myths.

He didn’t discuss his past in detail, or wallow in the tedium of a come-up story, so I piece together a train ride here, a bad contract there. There were the work-for-hire recording dates that allowed him to pay train fare and rent rooms, smooth-talking label owners who approached him with more terrible contracts when his sides made the Billboard charts, or misspelled his name on purpose so he’d lose track of himself and his royalties — and the women who dictated those erroneous contracts aloud like love spells, restoring some of his professional agency in exchange for his affections. He was never taught to read. He could draw guns quickly and had a close call with a career as a welterweight boxer. Muscle, charm and stature compensated for literacy’s absence. His is the Southern Gothic Hollywood story of my dreams and nightmares that I inherit as legends and lyrics. One of his songs in particular, an ode to Hollywood, turned that mythic image of him cinematic and drastically literal.

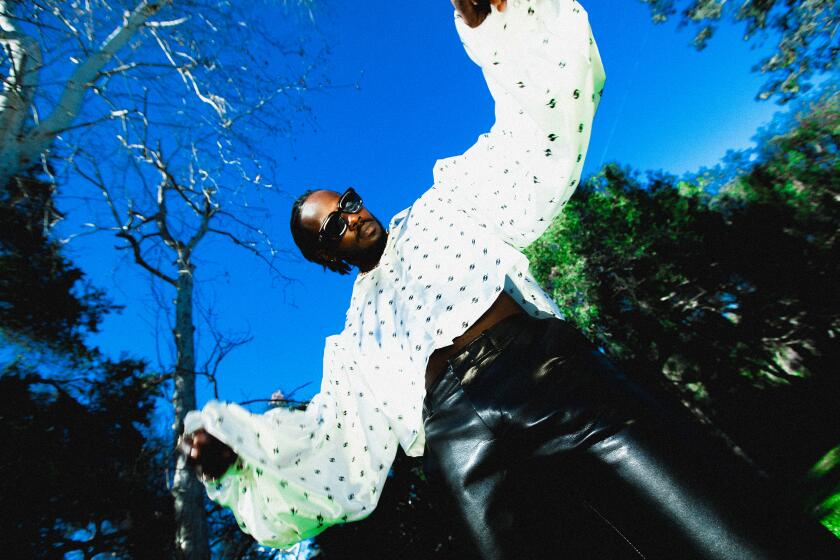

After half a century of hard living and hustle, the flamboyant storyteller from Pomona is learning to live with regrets and find peace.

Hollywood, California, wasn’t just a muse in the minds of residents in the Deep South where my father grew up; it was where you could self-exile from that destitution and turn work songs and praise songs into pop songs in exchange for access to the materialism that was at once owed and dreaded, glorious and taboo. My father fit the description; he was among those men and women who heard about Hollywood while working the field and refused to relent until he belonged to its star-making engine. Even the ability to retain such a fantasy was unspeakably bold at the time, but the gall to act on it is what made some of the first stars: Sam Cooke, Tina Turner, Sammy Davis Jr. and countless others. They were fearless, fearsomely exploited, vengeful and devoted to the image of them that could be sold. What mattered most is that they were there and had witnessed that other America. They had invented themselves in Hollywood, using the momentum of stubborn hope and daydreams, and they were the life of the party. Later, their sad parts were endlessly euphemized until they could be mistaken for happy endings.

In 1965, when he was signed to the Everest label, my father wrote and recorded an homage to “Ol’ Man River,” for which the B-side was the song “Hollywood,” a glorious entertainment-industry spiritual that projected all of his personal charisma onto the star map. I’m gonna save my money and take a very fast train/ and I’m not gonna leave until I have myself a name. I would leave this town today, if I only, only could. I can’t wait, I can’t wait to get to Hollywood, he declares in earnest. Hollywood survives on this longing for the idea of it in the minds of men exactly like my father, and one in a million of them make it there and then really make it once they arrive.

As a singer, my Jimmy Holiday embodies both the movie star and river man being carried by the momentum of hard labor. He plays the laborer and the free-spirited drifter who would never succumb to the burdens of economic hardship. He is Ol’ Man River Goes to Hollywood, a pulp fiction I unpack again and again until I can comprehend the lucid delirium he must have endured to live through those two opposing circumstances. He upholds a sense of dignity about working the fields, but no sense of disdain for his Ol’ Man River, who exposes how absurd it is to be exploited, and promises a future abdication of all that. “Hollywood” is that acquittal, that glorious quitting of sorrow in search of the pleasure boat. He sets out whimsically, I know there’s a place out West called Hollywood/ Where a guy with a lot of style could sure make good. He needs reprieve from his small Delta town, his natal occasion, but without undermining the soul and perspective it affords him. You have to take the singer’s word for it when he tells us he can’t wait because he sounds patient, methodical, like a suitor pining after the love of his life.

The L.A. artist taps into the ways in which God shows up, and how to honor that in real time.

Back home by the river, the cat don’t plant no cotton/ men like me that bled some/ are soon forgotten, he enjambs, inventing a foil for his lived experience. This was around the time many families from the region he grew up in survived on $400 a year. You and me/ we sweat and we strain/ bodies all aching and filled with pain. It’s an inverse work song, one that juxtaposes hard toil with a flow that cannot be interrupted by the frustrations of the proletariat. There are many identically titled odes to the soul of the Mississippi River. They create a universe that can only be understood as pre-“Mississippi Goddam” in sensibility. That is, before Nina Simone made militancy and nostalgia for home compatible, a hard task when one of the primary conditions of home is oppression. But back in the old world, Frank Sinatra was making a cameo singing here we all work while the white folk play, in his attempt at an “Ol’ Man River.” Double take. There is a lyrical blackface lurking in the American Songbook that implicates and disorients all of us. Hollywood paints it blue.

When I wasn’t preoccupied deciphering received narratives about my father’s experience navigating that land of appropriated lyricism, I could sense the mask he had to put on to survive it. He did take that train; he did arrive in Hollywood. He did make good on a rural interpretation of metropolitan glamour. His is the kind of story that is equal parts trauma and glory, that seduces someone like Frank Sinatra or the Rolling Stones into lyrical blackface.

Jimmy’s entry began with an invitation from Ray Charles after a week spent sitting in his office waiting room with a briefcase full of demos: “Let that n— in,” Ray instructed his secretary. And his idol became his collaborator. Nearly overnight, Jimmy went from an inconnu to welcome everywhere in town. He quickly developed a reputation for being a gun-toting, switchblade-carrying man on one hand and an impossibly tender soul who could write love songs with the facility of angels on the other. I’m told he would perform outlandish grand gestures that amplified the rumors about him. I’m gonna see my name in lights, like I always knew I would, he promised in “Hollywood.” He’d risk all that and go to a party at Sly Stone’s house and flip over a table full of cocaine in anger at witnessing his peers all using drugs, or so I’m told.

His recording catalog demonstrates his opposing gifts for hitmaking and staying true to soul and the blues, which didn’t always appease mainstream radio. It’s rich with love ballads, upbeat Northern soul originals and the hits he wrote for others, namely Jackie DeShannon and Ray Charles. Every once in a while, I’ll discover another artist I love has covered his most famous song, “Put a Little Love in Your Heart,” most recently the Isley Brothers. If it’s not his peers, it’s Coca-Cola or the U.S. government — like the time the song played unassumingly, ominously, as red and blue balloons fell like teardrops onto George Bush’s victory speech stage. The humiliation of the millennium, I thought then, making my dad an accomplice of the state. I tried calling the network in real time to demand they take it off. The phone remained limp in my palm for hours, teasing me with new routes to nowhere. I was just naive enough to be spared resentment and hesitation. I was just disillusioned enough to try out the involuntary optimism I’d inherited from my dad on anyone who violated the family name.

I had a keen awareness of how the famous songs usually aren’t the best ones and are often the easiest to co-opt. Relatability and mimic-ability are more valued than innovation on the airwaves. But fame has a way of upgrading your perception of everything it touches; it installs a gloss that no one likes to revoke — the illusion it supplies is too effective an opiate. We address the famous music and those who make it as if they’re infallible. We trust it at face value like seasoned melody junkies.

With a new EP and outlook on life, the L.A. artist is reaching toward his truest self.

I felt this a grave injustice as a kid, comparing my Jimmy’s popular songs to his best ones, negotiating with my own taste for compliance with mass cultural tastes and preferences. I didn’t like the fact that he belonged as much to his audience as to me when the pop songs came up in conversation, and how the industry seemed intent on diluting him into greeting-card soul music when he had made grimy and strange and irreducibly real tracks. Stubborn and forlorn about a legacy I couldn’t control, I learned to privilege the B-sides, both in the literal sense and in the narrative realm. I chased the fray. I uncovered the songs that never made the charts, scattered on dusty 45s on eBay, or in my friends’ crates, and I reclaimed those. Alongside them I reconstituted events out of fragments hushed and whispered by his nervous associates who seemed to fear my dad’s ghost as much as they had his person. I constructed a vulnerable, broken, villain-savior archetype out of a dead man.

Oh I get weary and sick of trying/ tired of living, in fear of dying, he surrenders, by the end of “Ol’ Man River.” I’m prodding, hold on, from the future. Spacious marching drums amplify his confession as he switches from lighthearted agony to Nat King Cole-style vocalese. By the final verse, he tidies it up and proposes overcoming his exhaustion, for the river. The man he was remains afield somewhere, still being mechanized for the textile industry, an estranged asset of another country masquerading as free. That private weariness caused him to recoil for long periods after his most outrageous escapades would get him sent to hospitals for electroshock therapy. But the anarchic spirit would return. He’d reclaim his Hollywood shine and be found driving the same car as O.J. Simpson in the Beverlywood neighborhood they both called home. They’d wave to one another in their matching red convertibles. Later, maybe that same day, Jimmy would be found holding a studio engineer in a chokehold for working too slow and running up his bill.

Devon Tsuno interviews Alan Nakagawa about forgotten stories of Japanese people in Mid City.

In 1968, he collapsed onstage while performing and needed heart surgery shortly after — all that work from the cotton field to the recording studio and all that travel he would never reveal much about had finally caught up with him. “Put a Little Love in Your Heart” was recorded the next year. It heralds “Ol’ Man River’s” heartbreak, the way enough time in Hollywood domesticates even the freest spirit into commercial relatability. It’s his capitulation to what he knew would sell mixed with his firm grasp on his prevailing value: that love is supreme and unassailable. That love wins even when it takes you under. The symmetrical singsongy cadence of “Put a Little Love in Your Heart” makes the offbeat hymnal nature of its composer almost unknowable; it banishes him from his own center stage somehow, so that an ideal can live past and exceed him.

As his daughter, inheritor of that decadent approach to love, that saccharine but beautiful popular song is a buffer that I use to protect the version of him that the song shrouds and resolves too easily. The proliferation of the popular songs allows him some secrets and hidden tracks that can never be co-opted — no American president wants to take a victory lap to “Ol’ Man River’s” casual tragedy. But all of them will clap offbeat to “Put a Little Love in Your Heart,” I solemnly swear.

Jimmy’s interpretation of Hollywood floating on the Mississippi River makes me feel safe that way and restores my esteem for both places. Not even Huck Finn would feel entitled to shepherd such a dreamer. Bye, bye, baby/ I’ll send for you/ Ain’t got much money right now/ I’ll come back a millionaire, he croons softly, loftily, at the end of “Hollywood.” The song is already fading out by then. You’d have to be up at 3 a.m. in huge headphones waiting for the parts that others will dismiss to catch it. It might feel like running to catch a train that never comes while realizing you’re already on it.