The industrial food supply will be the last bastion of the luxury economy, and we might mirror the cannibals in doomsday movies before we cede our idiosyncratic eating habits to austerity.

Capitalism is amazing because it inspires unrelenting competition between brands and the branding of items that should be generic — organized and categorized by which boasts the best flavor, the most sustainably sourced ingredients, or fastest-ripening produce whose side effects might include the leaching of toxic chemicals into municipal food and water supplies. Then, these same brands dutifully patent an expensive snake oil antidote for poisoning you. The side effects of the contaminants might reveal themselves in the body as mineral depletion, heavy metal overload or lethargy (chronic fatigue, leaky gut, hyperactivity, dissociation, anhedonia). Luckily, the same system that instigated mass disease and physical and psychic atrophy can invent a market for “clean eating,” the branded backlash against factory farming’s poisoning and genetic modification of your food and soil and water and air.

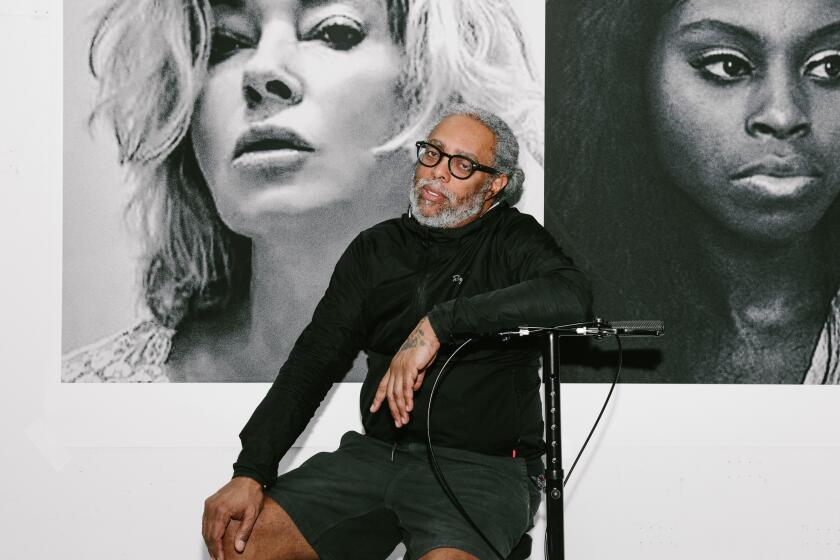

“Black Twitter: A People’s History” traces the path that Black Twitter took in becoming an arbiter of cultural shifts time and again.

What makes late capitalism even more special is that it can short-circuit just well enough that the so-called clean or whole foods deter most of society from examining where their food comes from and how it reaches them. What is a farm? What is a supply chain? Who are the farmers harvesting your food and the truckers driving it on interstates to you? Do they earn a living wage? Do you? What is topsoil? What is a supermarket? A muse for Allen Ginsberg, whose ecstatic litany of a poem “A Supermarket in California” captures the orgy of too many and just enough options, the numbness of excess. We forget that litany of questions under the fluorescent beams. Such are our funeral parlors for food, where mechanical reproduction haunts nourishment and we eat from the giant slot machines of industry. What is a supermarket?

In Memphis, Tenn., circa 1916, Piggly Wiggly opened its doors, offering the first self-service grocery vendor. Customers used carts and handheld baskets and ambled the aisles with their lists and often those lists expanded because there were so many products. Branding became essential to the differentiation that would earn the easy recognition and loyalty of customers, though labels about the purity of contents or lack thereof didn’t matter in this former landscape. What is called “Big Food” was born in the same region of the consumer temperament that brought us Elvis. By the 1950s and ’60s, middle-class and bourgeoisie America had a casual sense of access to meals and snacks and radio hits as if all were ready-mades built into their cities and suburbs like parts of a set. Personal fridges were stocked as well as the early markets but now there were more “processed foods” — frozen meals for lunch or dinner, an infinite variety of chips and dips for grazing. And the American teenager had enough disposable income to spend on frivolous quick food to accompany lighthearted music and lifestyles. The result is that we now have as many supermarket chains as we have categories of food product in those hallowed minor warehouses.

Before the self-service grocery, outlets required patrons to show up with detailed lists of items they needed and hand those lists to a clerk who would gather the items, which were either loose in bins or in flimsy generic packaging with no ingredients or labels. Today, this feels a step above state-sanctioned rations. At the same time, there’s a new niche market for containerless, “zero-waste,” grocery stores such as Re_Grocery in Los Angeles. And what these elite, boutique shops don’t necessarily realize is that they’re turning wellness into a luxury for the elite and those who replicate elitism for clout. It’s a sinister mode of decadence — decadent minimalism, where overt virtue signaling meets seemingly neurotic purity fantasies, where customers dance in the glow of the glare on bulk bins.

I remember supermarket parking lots from my childhood most vividly. There were times when my mom, my dad and I would make a trip for a jug of milk and my mom would go inside while we waited in the car. One such night my dad asked if we should leave her and drive away, as if to suggest before she owned us forever like the market. I returned a monotone no. The supermarket gave him a premonition of something sinister to come. In suburban San Diego, an area called Carlsbad, we’d call him from supermarket payphones as he sat in jail. His paranoia had been confirmed. And after he died and we moved to L.A., my mother went on her inevitable health kick-slash-healing journey. She hired a meditation coach who introduced her to Enya and a ’90s health-food chain called Mrs. Gooch’s. This store boasted muted neutral bins and amber-toned aisles, a drastic contrast from the buzzing neons of the popular chains. Instead of brand names like Fruit Roll-Ups, Mrs. Gooch’s carried fruit leather, made with real fruit, and it was tofu or other soy stuffed into the inner filet of the hot dogs instead of insinuations of pork. You could buy freshly pressed juices in glass bottles. On the way home, we’d stop for shots of wheatgrass. During her bouts of depression, she’d leave money on her nightstand and we’d walk ourselves to Vons or Ralphs and buy anything we wanted. At home, we had books on raw veganism by Dick Gregory and grape cures and detox methods and healing music. We had stakes in every market. We’d turned grocery shopping into a therapeutic symbol of semi-functional American family life, and of agency over our own lives. We were part of the group unknowingly beta testing the conflation of health, vitality and luxury shopping.

With two upcoming shows, one at Gladstone Gallery and another at 52 Walker, Jafa reflects on what it means to get a big break as an artist.

Whole Foods replaced Mrs. Gooch’s, but after being deracinated by Amazon, it became passé, less and less a signifier of status. Around the same time, terms like food desert went mainstream, defining the regions within cities where the only available food was the kind that is addictive and might kill you a little quicker. The newfound concern wasn’t accompanied by any remedy. The ability to articulate the struggle for decent food became another vain virtue signal.

And then came the rise of Erewhon, an upscale health food market that derives its name from the anagramic spelling of the word nowhere. It takes its name from a novel by Samuel Butler, in which ill health is a crime and citizens have to stay vital or risk incarceration — dark, with a little radiant grain of truth in depicting the persistent crisis of faith in the food supply. The market first opened in Boston in 1966, then reemerged in 2011 after a couple bought it from its original owner. Today a private equity firm — the Stripes Group — owns a minority stake, and the chain is expanding to every upscale neighborhood in Los Angeles. Thanks to the internet, its reputation transcends L.A. and has come to signify luxury eating nationwide. Tourists make pilgrimages to try its Hailey Bieber smoothie, replete with obscure superfoods and priced around $22. This is a typical price of an Erewhon smoothie. Everything in the store is organic, and local produce is prioritized. The aisles are sepia-toned and filled with everything from bone broth to raw fermented crackers to dried fruits (unadulterated by sulfur dioxide) to organic hygiene products to every brand of specialty water that exists in the world.

The prominence of Erewhon is the temporary response to the deterioration of Whole Foods, but its increasing popularity is also a reaction to the food scarcity trauma that 2020 instigated and the way we self-soothed with bougier tastes in food and wellness. It is no longer enough to wear designer- or even label-free “quiet luxury” clothing; the new way to indicate class is to shop Erewhon with no regard for cost and bypass the genetically modified, aggressively low-quality gut-busting food the U.S. is now renowned for. Celebrities shop at Erewhon and call paparazzi to photograph them there. Kim Kardashian collaborated with Balenciaga and carried a brown paper Erewhon shopping bag designed by the questionable brand to an outdoor L.A. fashion show. It was tacky. Influencers make TikToks and YouTubes taste-testing Erewhon smoothies and prepared foods mukbang-style. The satiety can be felt through the camera, its satisfaction with luxuriating in something so pure, so clean. And many of us have had slow evenings where we head there with a friend just to feel something. Erewhon is expanding to so many locations that the chain is bound to suffer the fate of Whole Foods and be replaced by a new, more conscientious iteration of the clean-eating superfood movement.

In the meantime, this aggressively revisionist supermarket, as indicated in Butler’s novel, has become part pharmacy, part a site of repentance for past consumption. We can’t see the farm from Nowhere. We are running on the energy of farmers’ labor and transmuting it into fetish object, and it feels almost beautiful on set in Los Angeles.

We’re in a game of survival of the fittest, where surviving itself feels akin to luxuriating in what should be hostile territory, mastering an environment we have come together to ravage. The next phase, of course, is making everything we consume from scratch like the tradwives and supermodels-turned-influencers. But you can’t buy their affect from Nowhere. It’s part Nara Smith, the German and South African supermodel who is now TikTok-famous for her gorgeous, tedious recipes for everything from gum to chips to real meals, and part Gwyneth Paltrow, who preaches her style of eating and sells it in batches that can be shipped direct to your doorstep, as if by a deity of celebrity fitness.

In the 1950s, he quickly developed a reputation for being a gun-toting, switchblade-carrying man on one hand and an impossibly tender soul who could write love songs with the facility of angels on the other.

Smith began making her food from scratch after being diagnosed with lupus and eczema. As a model and mother of three married to model Lucky Blue Smith, she has become the embodiment of luxury fashion meeting its lifestyle counterpart, with only a glint of moralizing. This family is almost perfect in its All American-meets-New American mode, like they were dreamed up in the Erewhon origin novel, with beauty as their alias, so you’d never know there are underlying health issues inspiring their commitment to clean living. Nara Smith is idolized and also ridiculed, but the unbothered serenity she channels in every video is eerily effective. She manages to be vulnerable, venerable, semi-transparent and entirely opaque, like any of the great gurus. “Do as I do, but you can’t because you’re you and I am the embodiment of pure luxury” could be her slogan. You just wanna try the lifestyle out, slow down, buy a mortar and pestle, marry a devout model, and see if living that way is akin to falling in love, becoming a teenager again, sharing a sugarless homemade soda over whitewashed doo-wop while the wars cold and hot proliferate abroad.

There is rampant spiritual sickness pervading the West, and what is called luxury, in every area of life, seems to soothe its symptoms. When it comes to food — shopping for food like our lives depend on it, but casually, in refined and enchanting micro-climates — the spirit seems to swell with optimism at the thrill we feel when we pay more for the false security of organic, non-GMO, seed oil-free, Nara Smith-approved groceries. My mother, widowed but loyal to the lifestyle market as if it would protect her from the alienation of child rearing, was onto something. This is where the elite go to abandon and redeem themselves, where the almost elite go to feel like what they may never be and claim a lifestyle just beyond their reach, for now. Who could blame them?