Word has been out for some time now: A freeway is anything but free. If you don’t believe the literature or the FasTrak tolls, believe your eyes. Visually, whether in the movies (think “La La Land”) or on your morning commute, the freeway is a creation that tells on itself. It can only carry you so high. A marvel of 20th century design, it is a form of conveyance limited as much by engineering and politics as by its own promise: efficiency. “If only we had more lanes, bro.” The memes always contain at least a grain of truth beneath the hilarity. If the freeway can’t deliver what it says, give it more of your efforts and more resources until it works as it was designed.

Admittedly, it can be difficult to envision a better way when such a solid structure — never mind the cracks in the infrastructure’s armor that politicians fear but won’t fix — is blocking your line of sight. The talk about what needs to happen can go on forever, which is why we decided maybe it’s time for a little show not tell. We asked several artists — William Camargo, 3B Collective, Patrisse Cullors and Devon Tsuno — if they were game to work their magic. The prompt? Press the delete button on their freeway of choice. They obliged, did their history, mined their lived experience and pulled from the vast troves of source material to liberate the freeways from themselves. Their genius works are an open call to keep the good times rolling. If we said when you woke up tomorrow that you could vanish the freeways — be it the 10, the 91, the 118 or even the East L.A. Interchange — would you dare to commit? The call is coming from inside the house to free the freeways and look directly at the brave new world. — The Editors

William Camargo, California 91

I’ve always lived adjacent to the 91 Freeway. It’s literally separated by a wall. It’s also the freeway that I drive the most on and that my family grew up driving on to visit relatives in L.A. The area where it’s located, in Anaheim, is one of the densest places in the neighborhood. There’s this little park, and growing up, I thought it was a pretty big park; it wasn’t until I went to other cities that I realized it’s actually a tiny park that’s between the 91 and the neighborhood. So I’ve been thinking about the possibilities of having more space — having something to replace the freeway, something better, that the community can use — dogs, pets, families, everyone.

In my art, I’m known for my signage work. The name of the series in which I started using signage is called “Possibilities.” Borrowing from Afrofuturism, I’m always thinking about what is the possibility of the future. For this piece I’m thinking of spaces that can be used for businesses, but also for leisure and playtime. One of the ideas that came to mind was an outdoor swap meet I miss that we used to have near Angel Stadium. On weekends, that was something that we used to do as a family — spend two, three hours there, buy some tacos, some nachos, and sometimes leave without buying anything, or just with tennis balls to play with in the neighborhood. And the other thing is green space — more park areas, especially noticing that there were a lot of kids in my neighborhood that had asthma. I myself have sleep apnea — I don’t know where I got it from, but I’ve noticed that when I’m in greener areas my sleep apnea kind of dissipates. I grew up around cars most of the time, and just constant noise. I can’t sleep sometimes now without that buzzing freeway sound.

I’m an adjunct professor at three universities, so I’m constantly on the freeway. But if I had the option to take public transportation, get work done on the train and not waste too much time sitting there, just staring into the massive traffic that we have, I would, which taps into the mental exhaustion spent on the freeway. I’m used to the exhaust, the gas, the pollution — it’s always lingering with me when I go somewhere else. I still smell it.

Architecturally, freeways are kind of ugly; there’s always construction going on, especially in California, which is always trying to expand the freeways. What if we did the opposite? What if we got rid of them, and what could be replaced?

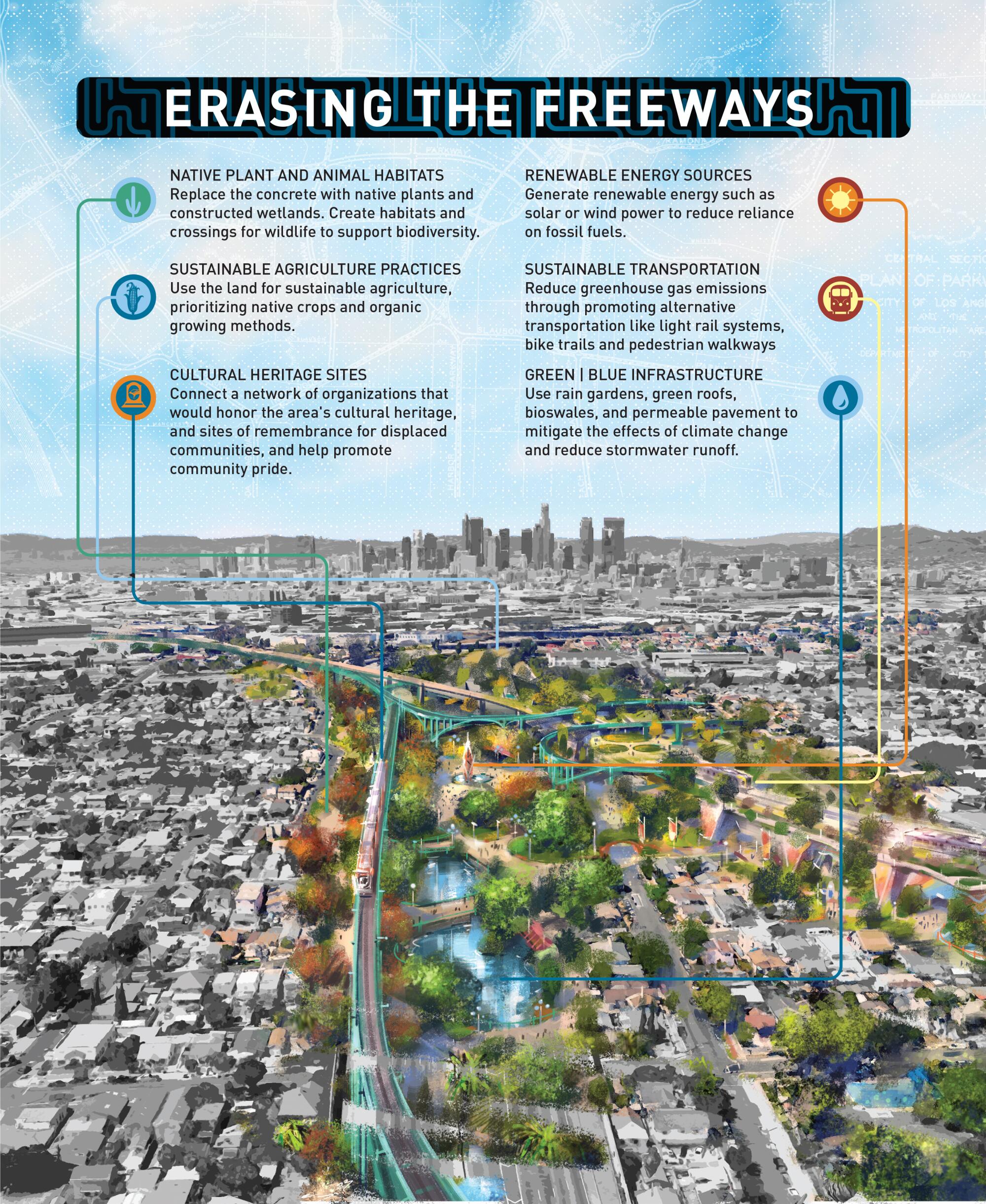

3B Collective, the East L.A. Interchange

Why the East L.A. Interchange? For the last few years, we’ve been working on an idea that began with a show in San Diego called “By Way Of,” centered around the freeway connections from L.A. to San Diego. From physical and psychological health effects to environmental impact, we wanted to draw attention to the effects of these massive interchanges. As we delved deeper into the impacts of freeways, the East L.A. Interchange quickly became the most significant interchange we could find in Los Angeles because of the vast amount of people and communities it has affected.

We continued this with our exhibition “Highways & Byways” at Residency in Inglewood and most recently with our mural “Aguas” at UC San Diego, where we again highlighted the massive barriers so we can start to reimagine land use, especially land that is currently taken up by freeways.

The question is, what would we do with all this land? Our approach is different from the typical Western way of thinking, which often prioritizes development over sustainability. We’re looking to make something sustainable to minimize the effects of carbon, carcinogens and other environmental pollutants. Our approach includes capturing rainwater, using different plants to help clean the soil and investing in public transportation, rather than massive infrastructure projects prioritizing individual modes of transportation. It’s important to note that there’s already a clear path toward sustainability. The science is there, the information is there.

These changes are not imaginary or impossible to implement. We already have a clear example up in Chico, Calif. There is a brewery that is almost zero-waste on site, thanks to their innovative use of rainwater and natural resources. We believe that we should move away from Western thought and instead focus on Indigenous ways of thinking that use natural resources to promote sustainability.

Part of what has influenced us greatly is the story of the South Central Farm, where developers and communities clashed over land use. How do we bring people together? How do we learn about natural remedies, including plants, and pass that knowledge on from one generation to the next? All of this was very clear within the South Central Farm, which was ultimately wiped away and bulldozed. We hope that some of that spirit can be brought back to the community, and the land that freeways occupy could be the key. Instead of them being barriers, we could pull them apart and bring the communities on separate sides of these walls back together.

Patrisse Cullors, California 118

In this work, I’m disappearing the 118 Freeway. It’s also known as the Ronald Reagan Freeway. It’s the freeway that we took frequently to visit my great-grandmother who lived first in Pacoima, and then moved to Lake View Terrace. She moved to Lake View Terrace after the 118 Freeway disappeared her home and disappeared Pacoima, which was a redlined community, and it was mostly, if not all, Black people in this community. There’s also a deep irony that I’m disappearing a freeway named after Ronald Reagan. While he’s not alive, he is probably the president who single-handedly created the infrastructure for mass incarceration and overpolicing in communities across the country, specifically in Pacoima area and the communities that I grew up in Los Angeles.

I’ve been doing a ton of research on the history of Pacoima, prior to my family living there. Before the Spanish colonizers came to Pacoima, it was called Pacoinga, which was a Tongva name. The community that lived there precolonization was a Tongva community that resided in these really beautiful dome-like structures. Before Hansen Dam, the Indigenous community said that there were these waterways that would run through Pacoima, right below the mountain ridge, so they were able to use water — the water was so available and resilient.

I’m developing a village that is a visual landscape using mud cloth — which is a textile material that I’ve been using from the Mali people — with yarn and cowrie shells that’s creating the landscape. It’s essentially one of the Tongva homes and then my grandmother’s home, so it’s this Black and Indigenous village. Living in Los Angeles, the Black and Indigenous connection — sometimes folks call it the Black and Latinx connection — is so important and visible, and I just thought it would be beautiful to imagine what it would have looked like to have this Black and Indigenous community live hand in hand with each other if colonization didn’t happen, if the redlining of communities didn’t happen.

My work in activism started as an organizer for climate justice. One of the big moments that you have when you’re a climate justice person living in Los Angeles is the role of the car and its impact on climate and greenhouse gases — how much freeway lobbyists are in favor of not stopping climate change because auto has been such a lucrative business and the freeway is the engine that continues to allow that business to thrive. Part of the many demands of growing up in Los Angeles as a climate justice organizer was to challenge the auto industry and the lobbyists who focus on the highway versus a first-class bus system in L.A. I used to organize the bus riders’ union, and that was one of our biggest demands: Let’s make a first-class bus system, so we don’t have to rely on the auto here in Los Angeles. This project, for me, is really special. It feels like it’s tying back not just to my roots and my family, but also the roots of my organizing in which the disappearing of a freeway is a literal demand of many people.

Devon Tsuno, Interstate 10

I feel like freeways are a negative thing that tear us apart from our communities, because we have to spend so much time on it. To be really honest, the freeways — and the ability to move from one place to another — are a function of capitalism. Anywhere that’s within an hour of where you live, there’s an expectation that you should be considering the freeway for school, work or whatever.

I was an adjunct professor for about a decade, driving all over Southern California. I spent so much money on gas and time in the car — like 300 miles a week. For me, that distance has been really traumatizing. Really exhausting.

My dream was always to work in the neighborhood I grew up in, [have] my kids [go to] school in the neighborhood I grew up in — to do things like in the neighborhood I grew up in. My mom’s family, my grandma, my parents, they live in Jefferson Park and went to Dorsey High School. I went to one of the original four L.A. charter schools, in the Palisades. My parents and aunts and uncles thought I would get a better education if I hopped on the bus and was taken to a more affluent area with more resources — that kind of thing. And I hated it. I hated leaving the neighborhood. I hated not going to school with people I grew up with in my neighborhood. I became further and further disconnected from my childhood, and the people in my own space, because I had to wake up at 6 every morning, hop on the bus, go all the way out to the Palisades for high school.

You spend so much time playing connect the dots to survive in the city.

I decided I would like to disappear the 10 Freeway and turn it into a major waterway, a water highway for nature. Nature is the thing that I’m always searching for. Being in the car on the freeway is such a function of being an Angeleno in that you’re a commuter in that space. So I turned that commuter space into the space that I desire — a natural space, a river, a native space, where it’s a highway, not just for us to destroy the environment, but a highway in which animals could thrive. You know, restore an element of what the space used to be when Indigenous people were true protectors of this land. That’s a fantasy that will never happen, sadly. This year, we had record rainfall, and all that water just went into the L.A. River and got dumped right out to the ocean; it wasn’t recaptured. But if there was a natural waterway, where water was recaptured by nature, that will be even cooler than recapturing it for us, for human development. Capturing the water for native animals and restoring that native landscape would be even more of a fantasy. So that’s what I did.

I did a water painting, thinking about those ideas, thinking about the color and energy that exists in thinking about that disruption and the struggle and hate that goes along with the freeway. I put it into this narrow rubric of abstraction that interests me, a very cerebral space. I was working in that space, actually constructing the water out of the pain. I thought that would make more sense for me. Then I had a photograph taken. We photographed from Crenshaw, going over the 10 Freeway all the way downtown with the foothills in the background. Photography has always been part of my practice, and overlaying photographs on top of my paintings — a collage on top of the paintings digitally — I’ve been doing for a while. That’s what I thought would be cool: to put that photograph we created and then make it black and white, bringing it over the painting. Then photoshopping and deleting the freeway, so you can see the painting through the photograph. Eating away at the freeway, literally.