L.A.’s streetwear shops took a big hit. Now owners want to rebuild, reunite

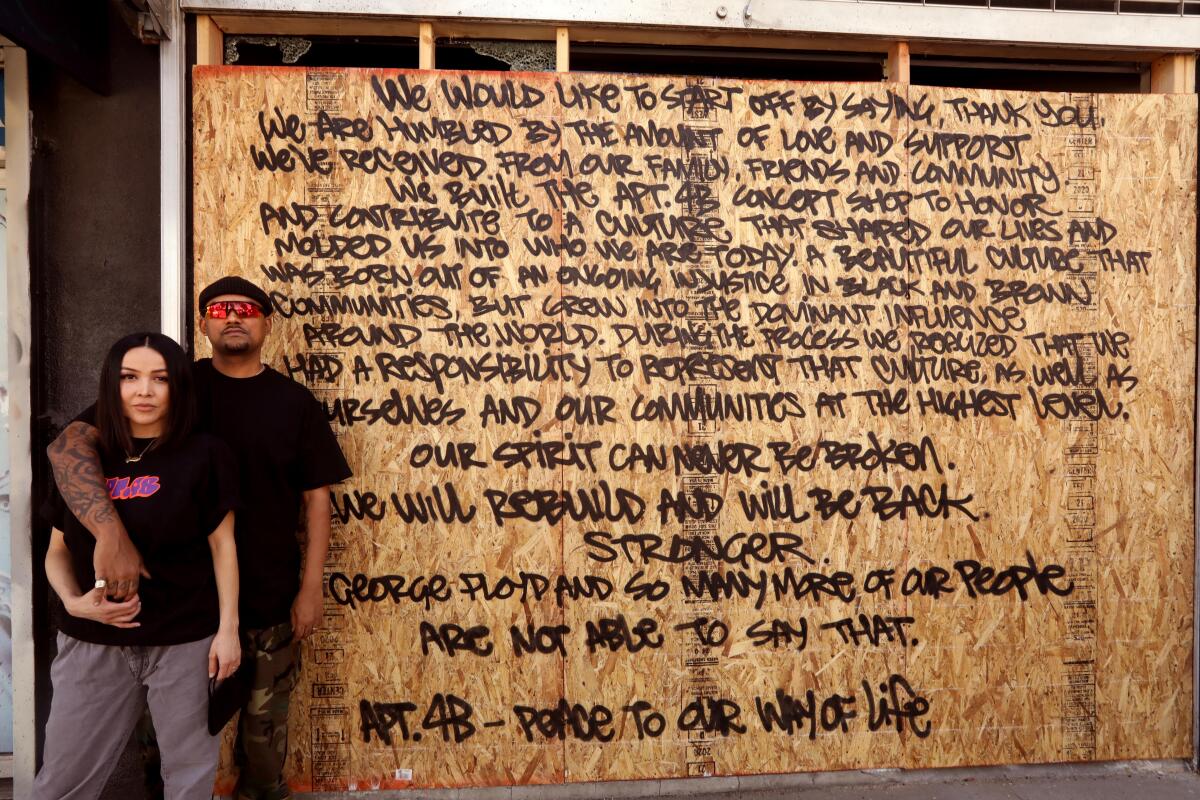

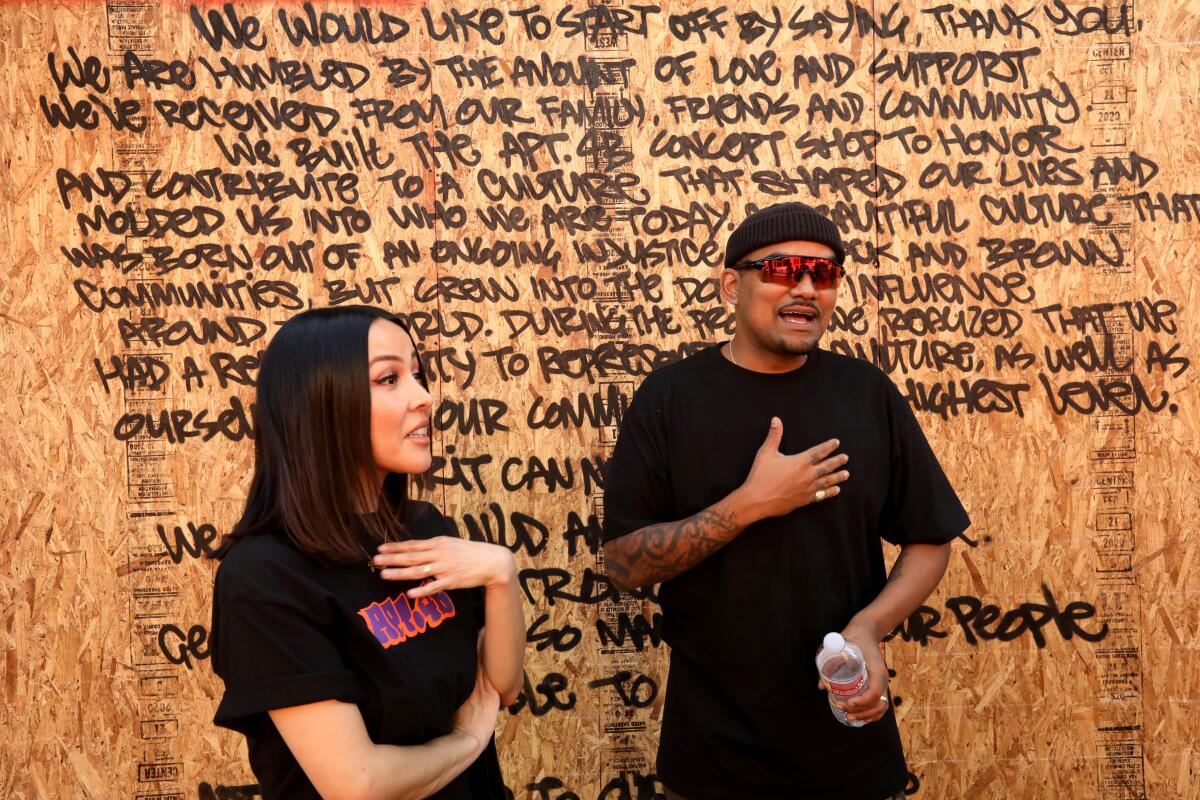

Less than a week after their retail concept shop was burglarized on Fairfax Avenue, Apt. 4B co-owners Moon and Monique Moronta stood in front of their devastated storefront as graffiti artist Josh Geisler, a.k.a. Self Uno, spray-painted a message of unity onto wooden panels covering the shop that opened in 2015.

Apt. 4B, which sells original streetwear apparel, was designed to look like a golden-era hip-hop apartment in New York, where Moon is originally from.

The message was the couple’s statement to their community in the aftermath of the late-May uprisings in the Fairfax District and other parts of the city, and it ended with the words, “We will rebuild and will be back. Stronger. George Floyd and so many more of our people are not able to say that.”

As coronavirus restrictions lift, firms are getting back to business and hoping for your support. Here’s a list.

Apt. 4B was just one of the many stores burglarized in the Fairfax District during the last weekend in May on the heels of peaceful protests following the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police on Memorial Day.

Now, shop owners, many of whom are people of color, are dealing with the aftermath of the break-ins and grappling with their own feelings about racism in this country.

Bobby Kim, co-founder of the Hundreds on Fairfax Avenue

Kim’s L.A. store, which opened in 2007 and sells a range of streetwear clothes featuring an animated bomb logo, still sits mostly unharmed at the corner of Fairfax and Rosewood avenues. A few tags on the building have already been buffed, except for one on the boards covering the front of the store that reads “BLM,” short for Black Lives Matter, in red. Kim decided to leave it.

Kim, author of “This Is Not a T-Shirt,” said the Hundreds is not his only source of income. However, because he works in an industry that runs on selling capitalist ideals to young people, he felt the need to speak up.

“That’s really how a lot of streetwear business is conducted,” Kim, 40, said. “It’s marketing and convincing young people that they need something that they really don’t need. ... We are at the same time teaching and training these young people to believe that they are of lesser value if they don’t have this brand — if they don’t have this pair of shoes — that they are not as worthy. They are not as full without wearing this hat on their heads.”

In a lengthy caption on Instagram, Kim took a strong stance in solidarity with protesters, writing, “Even if you bring the fire to my doorstep, I will stand in it with you.” A fire was set on May 30 on a corner near Kim’s store where police had created a barricade.

“I’m so much more angered and upset about racism in this country and police brutality,” Kim told The Times last week. “It’s temporary, some of this stuff.”

Kim, a second-generation Korean American, attended Black Panther rallies as a teenager. Although he doesn’t condone theft, he said, “No great significant civil-rights change has occurred without being on the heels of looting in some capacity.”

As Kim sees it, “This is not destruction and rioting and pillaging. This is people just trying to survive and be heard.” At the same time, he acknowledged that the situation is a complicated one, and he’s trying to hold space for conflicting feelings.

“Guess what? We can have both of those thoughts at the same time,” Kim said. “That’s why this is hard. There are no clear answers.” Chris Gibbs, co-owner of Union Los Angeles on La Brea Avenue

Because of streetwear’s roots in counterculture, Gibbs believes the community has a distinct perspective on this situation.

“Streetwear is a movement and a community that was started by young people in the ’90s [who] didn’t feel like they had a voice in fashion,” Gibbs said. “It’s a group of misfits. And by default that group of misfits is largely minorities, people of color, black and brown people.”

Gibbs posted his own message in support of peaceful protesters on Instagram on May 31, encouraging followers to focus on the genesis of the protests — black lives and police brutality — instead of breaking into stores. His post included images of Union’s metal roll-up gate, which deterred people in late May from vandalizing his La Brea Avenue store, known for its selection of up-and-coming streetwear designers and high-end brands from around the globe.

The gate recently featured a freshly painted mural, which read, “Stop Killing Us!” That was an idea conceived by Gibb’s wife, Beth Birkett, co-owner and creative director of Union and founder of the label Bephies Beauty Supply.

Gibbs tapped graffiti artist Yanta to execute Birkett’s vision the morning after break-ins had rocked the streetwear community, and it ended up serving as a crystal-clear message in unity.

“As a black man in America, [this] has been happening my whole life,” Gibbs, 44, said. “I’m excited that there’s some energy and people talking about the real issues. And I guess that’s what I want the conversation to continue to be.”

Gibbs believes many people who vandalized L.A. stores on May 30 had nothing to do with the Black Lives Matter movement and may have been targeting the area for more than a year. Although he doesn’t have concrete proof, he’s “almost positive” after speaking to fellow store owners. That’s another reason why he chose to shift the attention from the burglaries back to the protesters’ message.

Jimmy Williams and his son Logan are black owners of a popular Silver Lake nursery that sells organic vegetable plants and builds gardens for the rich and famous, but that didn’t stop the police from pulling them over in their work van one day, saying, ‘We’ve had several robberies in the area.’

Still, he recognizes that it’s a layered situation for many store owners, and he’s trying to show understanding for those who’ve reacted hastily as a result.

“I think for the most part this community is sad because the police are still killing innocent black people,” Gibbs said. “There’s [also] a certain part of it that’s like, ‘Yeah, our community has always been supporting these movements. So why target us?’ ... There’s anger, and that anger comes from both places. ... To not admit that would be lying.”Virgil Abloh, men’s artistic director for Louis Vuitton, founder of Off-White and cofounder of RSVP Gallery

Abloh, one of the first black designers to lead a French heritage house, got some heat after rebuking those who burglarized two of Sean Wotherspoon’s Round Two L.A. stores as well as Abloh’s RSVP Gallery store in downtown L.A.

“This disgusts me,” Abloh wrote under Wotherspoon’s Instagram post showing the trashed Melrose Avenue Round Two store, which sells vintage sneakers and clothing. “To the kids that ransacked his store and RSVP DTLA, and all our stores in our scene just know, that product staring at you in your home/apartment right now is tainted and a reminder of a person I hope you aren’t.”

After receiving a wave of backlash for his take on the situation and saying he also only donated $50 to a protesters’ bail fund — which he later clarified was part of a matching donation — Abloh posted a seven-page apology, detailing his own experiences of racism as “a dark black man. Like dark-dark.” Attempts to reach Abloh were unsuccessful.

In contrast, Golf Wang, the cult brand by music and fashion phenom Tyler, the Creator, posted this message in the comment section of one of the label’s Instagram posts, “[T]he store is fine, but even if it wasnt [sic], this is bigger than getting some glass fixed and buffing spray paint off, understand what really needs to be fixed out here. ...”

Moon and Monique Moronta, owners of Apt. 4B on Fairfax Avenue

When business owners found out a protest was scheduled to start May 30 at Pan Pacific Park — just a few blocks from the Fairfax District — some of them spent the day preparing for potential break-ins by boarding up their storefronts, adding signs to indicate that they were black- or minority-owned and, in some cases, stationing security guards.

Moon Moronta wasn’t one of them. He didn’t think he had anything to worry about.

14 California artists share their reactions to the protests over police brutality and injustice.

“Quite honestly, I did not think that it was going to come up past Beverly [Boulevard],” he said. “I felt really confident. I was like, ‘Naw, [the] LAPD is not going to let protests come up Fairfax toward these neighborhoods.’”

However, on the night of the protest, the Morontas anxiously watched the news and security footage from their phones as a mass of people inched toward Apt. 4B. Within minutes, the store’s security chain was broken and glass at the front of the shop shattered. Most of Apt. 4B’s clothing and hip-hop memorabilia was taken.

“We felt helpless,” Moon Moronta said. “We felt violated. It’s our baby for sure, and we couldn’t do anything to stop it.”

The Morontas, who live in downtown Los Angeles, arrived as quickly as they could to salvage what was left. Thieves had taken all but photography on the walls and a few cassette tapes.

The morning after the incident, large groups of volunteers cleaned up the remnants of the destruction throughout the Fairfax District.

Before the Morontas got to their store, their neighbors had already coordinated getting the shop boarded up. The following day, the Morontas got a call from marketing maven Karen Civil connecting them with rapper Russ, who donated $25,000 to them as part of a larger effort to help small, black-owned businesses affected by vandalism and theft. The couple also received a donation from a GoFundMe page, which has since been disabled. That effort was put together by Diane Abapo, a local photographer and magazine editor.

Breonna Taylor, 26, Tony McDade, 38, and many others didn’t live to see their 40th birthdays. They were killed by police.

“No one’s ever done that for us,” Moon said last week. “It’s incredible. My friend joked that we’re insured by the culture. That’s why … when people talk about ‘streetwear this and streetwear that,’ they’re disconnected in some way because that’s not what’s happening. … This is the community getting together.”

Although they were still grieving the recent loss, the generosity from the community has softened the blow for the Morontas and allowed them to look at the bigger picture: standing in solidarity with black lives.

What now?

Some shop owners, including Kim and Gibbs, are using the situation as an opportunity to do some reflection on their industry.

“We’re trying to put together some kind of coalition that addresses the issue,” Gibbs said of a process that’s in its early stages. “The issue is not our stores being burglarized or the looting. The issue is trying to stop police brutality. That’s what’s coming out of this, which I think is really beautiful.”

Kim has turned inward and is trying to understand his own responsibility in the matter. “When it comes to breaking people down into who’s good [and] bad ... and, ‘Oh, are looters bad?’ Am I not bad?‘” he said. “We taught these people to value clothing over culture. We taught these people to value sneakers over community. ... I’m partly to blame. … I take ownership in that.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.