Hispanic Heritage Month gets justifiable criticism, but it’s still worth celebrating. Here’s why

It happens like clockwork: At least one corporation ends up apologizing during Hispanic Heritage Month because their campaign intended to celebrate Latinos ends up offending them. This year’s loser is Twitch.

The Amazon-owned live video streaming platform issued an apology within hours of launching its campaign last month after users called them out on Twitter for the design of their Hispanic Heritage Month-themed emotes, which employed stereotypical and racist depictions of what Latinos are like.

“These were not an appropriate representation of Hispanic and LatinX culture, and we’ve removed them.” Twitch wrote on Twitter.

These corporate blunders have left some Latinos skeptical of Hispanic Heritage Month. Others take issue with the sanitization and whitewashing of how it’s celebrated. Despite all the critiques, the 30-day celebration — it ends Oct. 15 — still serves as a perfect opportunity for Latinos to celebrate and learn more about their history.

Stephen Pitti, a history professor and director of the Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity and Transnational Migration at Yale University, said some of this distrust can be seen in other Latino-specific holidays or events.

“I hear plenty of similar cynicism about Cinco de Mayo celebrations as having been taken over by corporate sponsors, or Puerto Rican Day parade celebrations as being no longer connected to community priorities, community leadership,” Pitti said.

But before Disney and Barbie co-opted it to remind you which parts of their intellectual property have Spanish surnames, Hispanic Heritage Month was originally intended to be a recognition and celebration of the many contributions Latinos have made to the United States.

In June 1968, Rep. George E. Brown Jr., whose district included large portions of East Los Angeles, introduced House Joint Resolution 1299, which called for the week that included Sept. 15 and 16 (two dates that fall on the independence day of many Latin American nations, including Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Mexico) to be proclaimed by the president as “Hispanic Heritage Week.”

The resolution was co-sponsored by several legislators from California and the Southwest, including Edward R. Roybal (who made many other significant contributions to the Latino community in Los Angeles) and even future President George H.W. Bush.

On Sept. 17, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed it into law.

“The people of Hispanic descent are the heirs of missionaries, captains, soldiers, and farmers who were motivated by a young spirit of adventure, and a desire to settle freely in a free land,” Johnson declared. “This heritage is ours.”

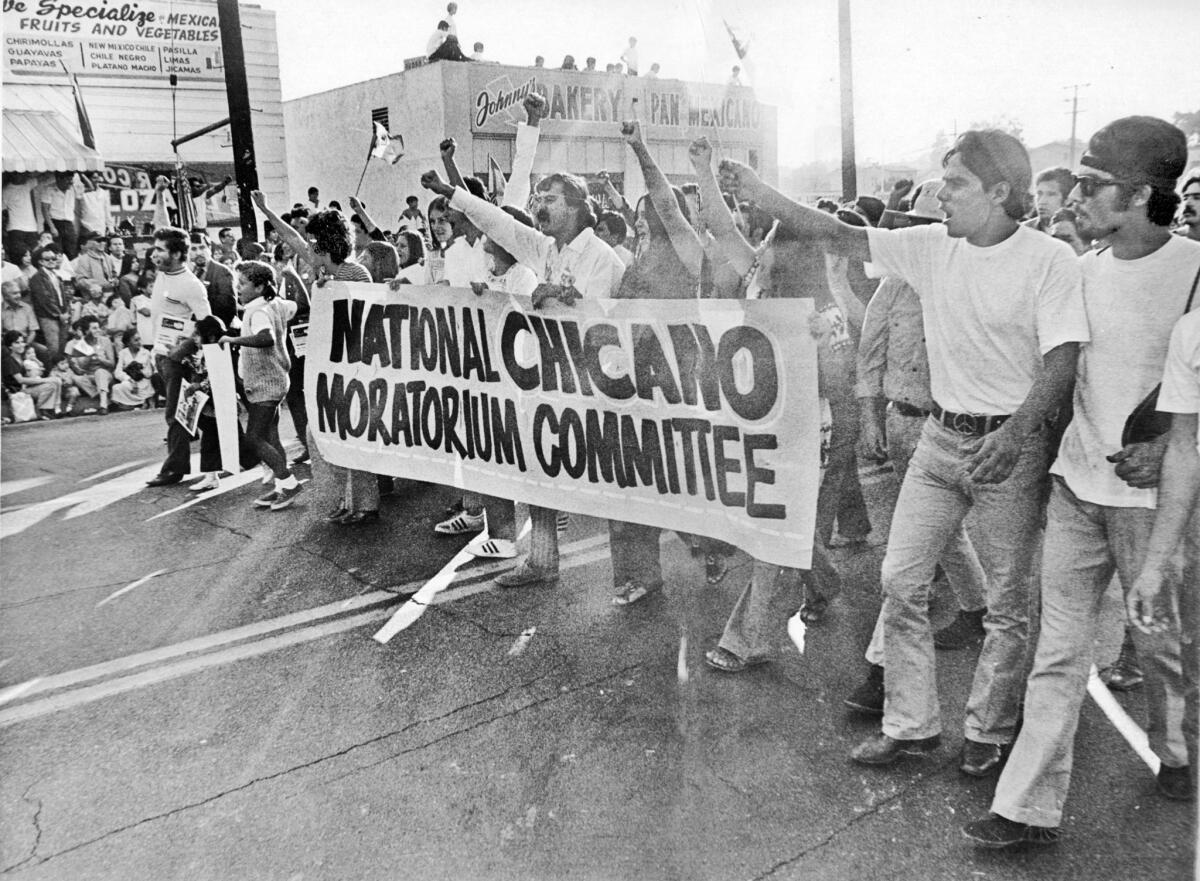

50 years ago, the Chicano Moratorium made an indelible impact on L.A. culture and civil rights. Explore the LA Times project.

That proclamation was significant because “it asserted that we are here and are part of this nation,” said G. Cristina Mora, associate professor of sociology at UC Berkeley and author of “Making Hispanics: How Activists, Bureaucrats, and Media Constructed a New American.”

“We’re not just bystanders and immigrants, but part and parcel and have created the history of the U.S.”

Twenty years later, new legislation expanded Hispanic Heritage Week to a month, keeping Sept. 15 as the start date and ending on Oct. 15. Robert Lopez, a former Times journalist and current executive director for communications and public affairs at Cal State Los Angeles, worked as an intern for the Congressional Hispanic Caucus in summer 1988, and was tasked with getting endorsements for the bill that was eventually signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

Lopez recalls how he learned more about the accomplishments of Latinos from the Congressional Research Service than from his formal education.

“I went to Azusa High, where there were many Latinos but there were no Latino or Chicano studies” classes, Lopez said. “I never learned about the contributions of my community because it was never taught to us. We were taught a version of history that didn’t include us.”

Working to expand a week into Hispanic Heritage Month “made me real proud, that we were doing a good thing,” he said.

In the summer of 1983, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Latino community.

Despite the good intentions behind Hispanic Heritage Month and its precursor, concerns about it remain and go beyond complaints of corporate “hispandering.”

The word “Hispanic,” which comes from the Spanish word “Hispano” (individuals whose cultural traditions originate from Spain), centers European whiteness. In contrast, the term “Latino” roots people’s origin in Latin America. (The Times style guide prefers “Latino” over “Hispanic.”)

“I don’t hear people talking too much about Black Hispanics,” Pitti said. “People talk instead about Afro Latinos or Black Latinos. The term ‘Hispanic’ overwhelmingly positions people as just descendants of Spain, and it doesn’t offer a lot of space for the recognition of indigenous and Black communities. The problem with that is that it’s historically dishonest.”

More enslaved people from Africa were taken to the Caribbean and Latin America than to the United States, Pitti noted. The focus on the Spanish side of Latinidad can be alienating to Latinos who don’t identify as white, leading some to reject it outright.

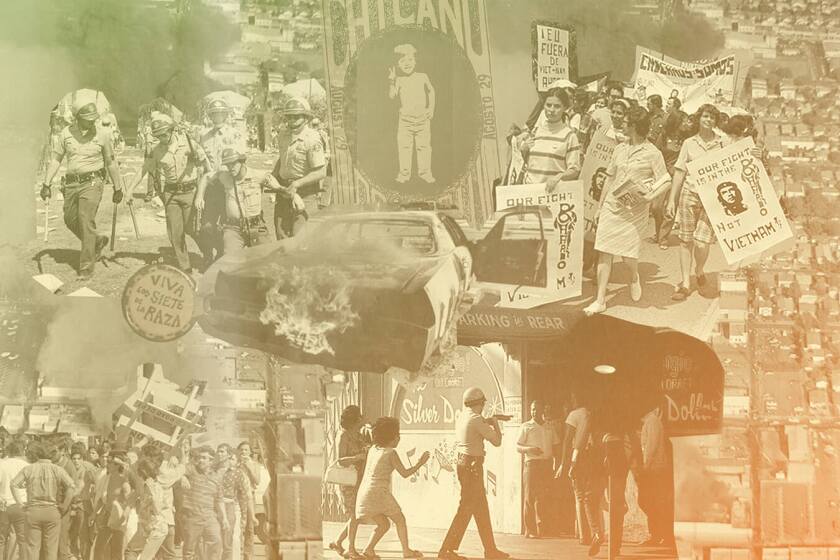

Another critique of Hispanic Heritage Month is that it sanitizes the actual history of Latinos in the U.S. every year, the accomplishments of people like Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, Sandra Cisneros and Roberto Clemente are touted in public service announcements on television. Less so are historical events like the Zoot Suit Riot, the lynchings of Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest, or the United States claiming Puerto Rico as a territory after Spain surrendered in the 1898 Spanish-American War.

“It’s a kind of whitewashing of the Hispanic experience in the way that it’s portrayed by corporate and governmental interests,” said Mario T. Garcia, professor of Chicana and Chicano Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “There’s no racism. There’s no conquest.”

But cynicism and shortcomings aside, Hispanic Heritage Month is an opportunity for Latinos to learn their history, the good and the bad.

“It’s not just an opportunity to celebrate what’s on the Latino food aisle, but to think of what it has meant that Latino suffering has been central in the way our community has developed and how that relates to the patterns we see today,” Mora said, pointing to how the vilification of Latino immigrants isn’t a new phenomenon, but rather part of an ongoing narrative that goes back centuries.

“The very names of our cities and our mountain ranges and our rivers,” Garcia added, “I say to my students, ‘Those names didn’t come with the Mayflower.’”

Still, he said despite the fact that there have been many contributions to the study of Latinos in academia, very little of that history has made its way into K-12 curriculums. That likely won’t change soon in California: On Wednesday, Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill that would require high schoolers in the state to take a course in ethnic studies in order to graduate.

That knowledge “hasn’t seeped down, so we may as well use Hispanic Heritage Month to correct that,” Mora said.

So with that in mind, and with plenty of time to still celebrate, here’s a list of books to help you learn more about Latino history:

“An African American and Latinx History of the United States,” by Paul Ortiz. Published in 2018, historian Paul Ortiz’s book retells the history of the United States by centering and contextualizing the role that Black and Latinx Americans played in its formation.

“The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas,” by Monica Muñoz Martinez. Muñoz Martinez’s book focuses on an untold part of history: the state-sanctioned lynchings of Mexican Americans carried out by groups of vigilantes and the Texas Rangers in the early part of the 20th century. A historian at Brown, Muñoz Martinez is also one of the co-founders of Refusing to Forget, a nonprofit organization that has helped put on museum exhibits on this very topic.

“War Against All Puerto Ricans,” by Nelson Antonio Denis. In 1950, the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party unsuccessfully tried to declare Puerto Rico’s independence with a series of armed protests. Denis’ book tells the story of an event which resulted in the only time in history in which the United States bombed its own citizens.

“Making Hispanics: How Activists, Bureaucrats, and Media Constructed a New American,” by G. Cristina Mora. The Latino community is not a monolith. It is formed from people with different countries of origin, of different races and even different languages. And yet, it’s largely understood that they share a history and other characteristics. Mora’s book chronicles how the broader idea of the “Hispanic” came to be.

“Blowout!: Sal Castro and the Chicano Struggle for Educational Justice,” by Mario T. Garcia. Garcia is considered one of the foremost scholars on the Chicano movement — he was recently cited in Los Angeles Times reporting on the 50th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium. “Blowout!” is an oral history of the 1968 East L.A. walkouts, a series of student protests that became a flash point for the Chicano Movement, as told by Sal Castro, a former teacher and an organizer of the walkouts.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.