- Share via

Lauren Soriente’s grandfather told her that he expected her to pay for her younger sister’s college tuition. When he was growing up in the Philippines, the oldest sibling paid for their younger siblings’ tuitions, he said.

Soriente’s mother, meanwhile, has been unclear about what financial support her parents expect from her — and unwilling to have a serious conversation about it. Years ago, the 27-year-old felt pushed by her family into pursuing accounting. It’s a field that offers financial stability, but it’s not something the Northern Virginia resident is passionate about.

“I guess looking back now, I realize, did they make me do this so I would be their retirement fund?” she said.

The possibility that she might have to financially provide for her family adds to the existing stressors she faces, with student loans, wage stagnation and inflation.

Soriente’s experience is common among Filipino Americans, who place a high value on looking after their families. The indebtedness Soriente feels and the expectations her family has are rooted in the cultural value of utang na loob, which translates to “debt of gratitude.” It refers to reciprocity and doing what’s good for the collective. In a listening session with 16 Filipino Americans from across the U.S., the majority of participants shared similar experiences about the pressure of putting family first as a common source of tension.

Christine Catipon, a senior staff psychologist at the UC Irvine Counseling Center, sees the effect of utang na loob in almost all her Filipino students. They often feel pressured not only to pay their parents back for all they’ve done but also to support them for the rest of their lives. For Soriente, she attributes the indebtedness she feels for her family to a strong sense of duty and close connection to family members. Also to the expectations they have of her, in part because they’ve fulfilled her basic needs.

This is a collection of articles about mental health in the Filipino American community and the factors that influence it.

What’s known about the nuances of Filipino American mental health is limited by a dearth of resources and researchers dedicated to studying it. One 1995 study found that 27% of Filipino American respondents had a major depressive episode or clinical depression of varying severity, more than three times that of the general U.S. population. Another study, published in 2017, found that Filipino American youths were at higher risk of depressive symptoms during adolescence and young adulthood compared with their Chinese American peers.

Dr. Joyce Javier, a pediatrician and researcher at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and an associate professor of clinical pediatrics at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, has conducted research on suicidal ideation in Filipina American teens. She said the group has been shown to have higher rates of suicidal ideation compared to other ethnicities.

Despite the fact that much is unknown, Catipon said a good place to start is understanding the role cultural values play when it comes to mental health.

Kevin Nadal, a professor of psychology at the City University of New York and author of “Filipino American Psychology,” cited four main cultural values that may affect Filipino Americans’ mental health. In addition to utang na loob, there are:

- kapwa, a sense of connectedness with one another.

- pakikisama, the idea of social conformity, the need to be accepted and for there to be peace and harmony among others.

- hiya, shame, which is “governed by the notion that the goal of the individual is to represent oneself or one’s family in the most honorable way,” Nadal writes in “Filipino American Psychology.”

“It’s so important to acknowledge that these values are generally good and positive values, and that they are the reasons why we have a strong sense of community, why Filipinos generally are a collective,” Nadal said. “They put others before themselves, are kind, hardworking and all these other things.

“And at the same time, these values might contribute to the nuanced reasons why some Filipino Americans may have difficulty navigating mental health issues.”

Catipon said that these values, which are familiar in the Philippines, might not be as obvious in Filipino Americans who were raised in the U.S., but they are often internalized.

Kapwa could prevent someone from seeking therapy, Nadal said, particularly if it involves going to a hospital or an area where a family member works. It’s a value that’s related to hiya. There is still a stigma attached to admitting you are having mental health issues, and this can lead people to avoid seeking therapy for fear of bringing shame to the family, community and themselves.

“It’s also the shame that people might feel that leads to things like depression,” Nadal said. “So if you feel shame that you didn’t graduate from college, or if you feel shame that you didn’t get married before you had a kid or you haven’t gotten married and you’re 40 years old, there might be lots of mental health issues that are attached to that.

“But maybe people aren’t connecting to those things or talking about those things because they just don’t want to admit to that — because talking about shame is hard and painful.”

If a family situation benefits the collective but causes an individual pain or suffering, that person might choose not to say anything because it might be received negatively by the entire group, Nadal said. This is related to the value of social harmony, or pakikisama.

He added that a person who does talk about it could be punished and be questioned about why they are causing trouble.

“This is why some Filipinos might internalize a lot of problems — because they don’t want to cause problems for others and their families or in their communities,” Nadal said.

The value of utang na loob, feeling indebted to others, can also contribute to suicidal ideation, Catipon said.

“There’s this inherent, ‘I did this for you, you owe me’ kind of feeling,” she said. “And if that’s your purpose, if you can’t pay them back, then what value does your life have?”

Javier said it’s difficult to pinpoint specific causes for high rates of suicidal ideation among Filipino Americans, but she cited three risk factors associated with it: depression, academic strain and family conflict.

“That’s a really important one, because family conflict can be a risk factor. But on the flip side, family closeness is a protective factor,” she said. “So there’s a lot of things that we can do to really help address suicide.”

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

Michelle Binoya, 33, a resident of Palmdale, was 15 when she first recognized she had depression. She also deals with suicidal ideation daily. She has often had to put the needs of her family before her own, including caring for her dad, who has schizophrenia. That came at a large cost to her and her family: Her mom wasn’t able to finish school and didn’t learn how to drive. Meanwhile, Binoya has repeatedly delayed graduating from college and doesn’t see herself getting married or having kids because she has prioritized attending to her father.

“I’ve always known that part of my issue with my mental health is my family,” she said. “And I don’t know how to love my family and maintain my wellness. And that’s the hard truth.”

She said her therapist has told her she should move out of the home she shares with her parents. Yet even with all the challenges that come with a parent who has episodes that can become violent, she’s determined to make her living situation work.

“At the end of the day, that core value [of family] is super important to me. I don’t know how it stuck with me, but it did. And I’m happy. There is a part of me that’s super happy and proud that I stuck it through.”

Catipon said many of her Filipino American clients withhold their mental health concerns from their parents because being “crazy” might make their parents feel like they’ve done a bad job of raising them.

Many participants in the focus group said they were taught to keep their emotions to themselves and not show others when they were struggling. Some also had their feelings dismissed growing up or didn’t talk about feelings.

That may prevent people from talking about suicidal ideation, Nadal said. Suicide is often so taboo that people won’t even label it as such, he said.

“Suicide among Filipino families — especially in the Philippines — tends to be covered up or hidden due to the stigma,” he said. “In fact, the Philippines generally reports a lower incidence than other Western countries, probably due mostly to the stigma leading to underreporting.”

Another part of the stigma of suicide stems from a misconception that Catholicism — which teaches that believers “should not despair of the eternal salvation of persons who have taken their own lives” — considers death by suicide a sin that without exception bars entry into Heaven. This can also contribute to people’s fear of discussing it.

Southern California mental health resources for Filipino Americans

SIPA (Search to Involve Pilipino Americans)

(213) 382-1819, Ext. 125

Center for the Pacific Asian Family

(800) 339-3940

APAIT Health Center

(213) 375-3830 (L.A. office)

(714) 636-1349 (Orange County office)

OCAPICA (Orange County Asian Pacific Islander Community Alliance)

(714) 636-9095

Pacific Asian Counseling Services

(310) 337-1550

Change Your Algorithm

(323) 663-8882

In an effort to reduce suicidal ideation, Javier partnered with community organizations, schools, churches, community members and local officials 11 years ago to create the Filipino Family Health Initiative, a culturally responsive solution to address Filipino American mental health. It does so by teaching parents how to build stronger parent-child relationships and pass down positive cultural values to their children, among other things. The organization runs workshops on effective communication, special time with children, and social and emotional coaching.

She also said that research shows that a child’s or teen’s pride in their culture and ethnicity is associated with more positive mental health outcomes.

“So if someone can associate being Filipino as something positive, then that is very protective for their mental health,” she said.

Catipon said younger generations of Filipino Americans appear more willing to seek therapy compared with a decade ago. It allows them to learn healthy ways of communicating and expressing their feelings, which reduces some of the shame around it.

Videos: Talking about Filipino American mental health

- Share via

Tess Paras talks about filmmaking, mental health and her Filipino American family

7:20

Christine Catipon talks about why it can be hard for Filipino Americans to talk about mental health.

2:26

Clinical psychologist Christine Catipon explains what "smiling depression" is.

1:30

Christine Catipon talks about why it can be hard for Filipino Americans to talk about mental health.

2:26

Clinical psychologist Christine Catipon talks about where to start with self-care.

1:28

Clinical psychologist Christine Catipon has advice for people who are called "too sensitive.”

1:43

“Even if they might not be able to express this with their family, they can at least not take responsibility for the ways that other people are going to choose to respond to them,” she said. “My clients are all about, ‘I want to learn how to take responsibility for my stuff and to recognize what’s not my stuff. [My family’s] doing the best that they can, but I’m learning how to do better.’”

Soriente said she experiences both negative and positive aspects of her cultural values on her mental health. She feels she’ll never fully meet her family’s expectations of her, but she’s working on accepting that.

At the same time, she acknowledges that it’s utang na loob that keeps her family strongly connected. She loves talking to her family about Filipino culture and food. She has also started learning Tagalog. She chats with her grandfather about her classes, and her mom helps her with her homework.

“I was raised by my grandparents, and I’ve always felt like their house is something I can always come back to,” she said. “Like, no matter what happens, I’ll always have my room in their house. I’ll always be able to go there for dinner.”

The impact of the value placed on Eurocentric features, such as lighter skin, in the Filipino community is one of the most prominent examples of the impact of the Philippines’ colonial history on Filipino American mental health.

More to Read

About this story

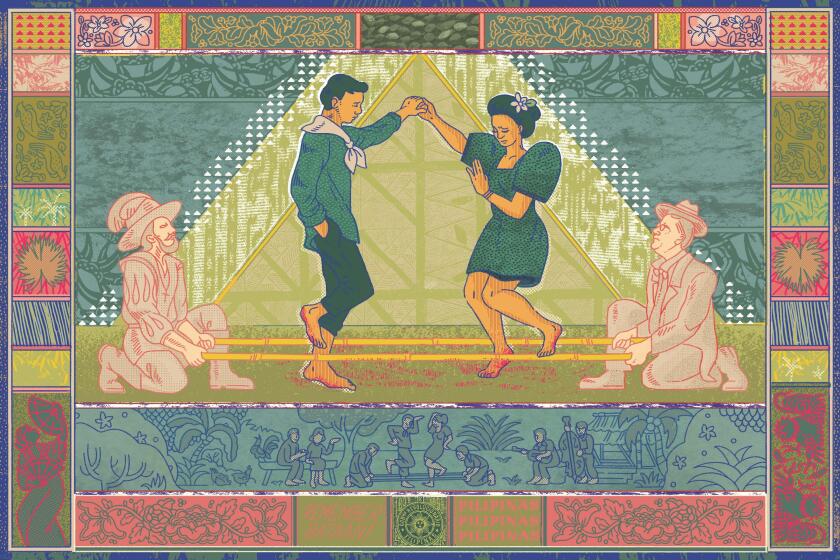

Illustration by Angelica Alzona. Art direction by Micah Fluellen. Videos produced, shot and edited Albert Brave Tiger Lee, with Utility Journalism assistant editor Ada Tseng and senior editor Robert Meeks. Additional camera by Jessica Q. Chen. Listening sessions facilitated by Constante, Tseng, Danielle Fox and Karen Garcia.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.