Your lawn will suffer amid the megadrought. Save money and put it out of its misery

It’s going to be a summer of brown grass and hard choices for Southern California lawn owners facing the Metropolitan Water District’s one-day-a-week watering restrictions starting June 1.

With just eight minutes of water once a week, the recommended amount people should use with traditional sprinklers, you can’t keep a lawn green. Period.

“Most lawns are going to go dormant, and depending on the grass, some will be a total loss,” said Jim Baird, a turf grass specialist at UC Riverside’s Turfgrass Research Facility.

The preferred variety in Southern California, fescue lawns, are used to getting water multiple times a week. The water-thirsty fescue will be hard-pressed to stay alive in communities facing water restrictions, which include about 6 million people in Los Angeles, Ventura and San Bernardino counties. And that’s just fine with people who believe ornamental or “nonfunctional” lawns are a colossal waste of precious resources in Southern California.

“If you’re playing soccer on it or using it for picnics with the family, fine,” said Evan Meyer, director of the Theodore Payne Foundation, which grows, sells and preserves California native plants. “But if your lawn is just ornamental, it’s indefensible given the reality of our water situation here.”

Rebecca Kimitch, a Metropolitan Water District spokesperson, put it more bluntly: “‘As we always say, ‘If you’re only on your grass to mow it, then get rid of it.’”

But turf advocates like Baird see the demise of Southern California lawns as short-sighted. Lawns provide a valuable service here because they reduce dust, sequester carbon and keep communities significantly cooler while making neighborhoods more desirable, he said.

For the last decade Baird has been trying to educate government officials and lawn owners about the most water-efficient ways to grow traditional lawns in this region. He suggests:

- Planting warm-season grasses such as Bermuda, Kikuyu and buffalo grass, which use at least 20% to 50% less water than the tall fescue varieties that make up the majority of SoCal lawns. (The downside: Warm-season grasses go brown and dormant in the cold winter months, especially in inland areas.)

- Not irrigating during the cooler winter months.

- Watering at night or early morning up to three times a week during the hottest months for two minutes at a time over several hours, so the water has a chance to soak in and not run off into the street. For example, a 14-minute watering session would be stretched out over seven hours from, say, midnight to 7 a.m. with the sprinklers staying on just two minutes at a time for each hour.

To his frustration, however, that’s not what people do. “Most people don’t even know how their automatic sprinkler systems work,” Baird said. “They just ask their gardeners ... to set the [sprinkler] clocks so the grass stays green, and the gardeners set the clocks to overwater so they don’t lose their jobs. I see people’s irrigation running every night and it’s so sad, because now the lawns will suffer because people waste water and faulty irrigation systems waste water. It’s not the grass wasting water.”

Water suppliers in parts of Southern California were ordered to impose severe water restrictions. Details of the new rules are starting to take shape.

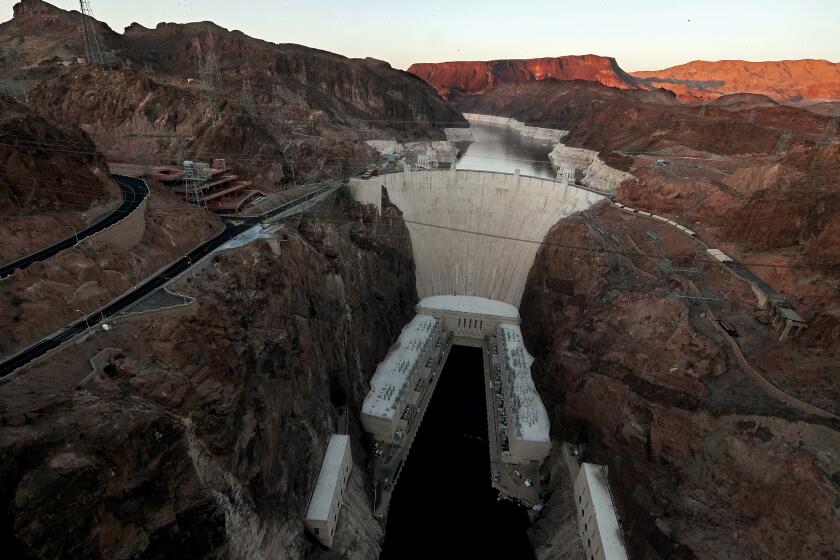

The stringent watering rules apply only to the MWD’s customers who rely on water from the severely depleted State Water Project, which historically collects about 3 million acre-feet of water over a three-year period, on average, but has collected only 600,000 acre-feet of water over the last three years, Kimitch said.

MWD also collects water from the Colorado River Aqueduct, as well as local sources such as groundwater supplies and recycled water, but customers in the crisis zone can’t get that water because their pipes are connected only to State Water Project supplies. It’s basically a distribution issue that affects about a third of MWD’s Southern California customers, Kimitch said. Meanwhile, other communities have more water available — at least for now — so you may see a patchwork of green lawns around L.A. as you contemplate tearing yours out.

Which is not to say that other Californians can just water with abandon. The ongoing megadrought, now entering its third year, is affecting the entire state, and every consumer needs to be reducing water use by 20%, Kimitch said.

“You may not be experiencing an acute crisis now, but you could be in four or five years,” she said. “When the crisis does happen, instead of watching your lawn die, you can be watching your beautiful California native garden thriving.”

So now is the time for affected lawn owners (and even the unaffected whose time with their turf may be short) to consider how to proceed when June 1 rolls around. Will you try to keep your lawn alive by weaning it off water in coming weeks or will you stop watering completely and start planning what to plant there instead?

You can get money for letting your lawn die, if you have a plan

The Metropolitan Water District’s Turf Replacement Program pays $2 a square foot for up to 5,000 square feet of lawn converted to approved “water-wise” uses in residential front or back yards (or up to 50,000 square feet of commercial landscaping), and some local agencies offer an additional rebate on top of that, which could mean a bigger payout once your work is completed and approved.

In recognition of the water crisis, MWD has extended the deadline to get lawns removed and new water-wise plants installed, Kimitch said. In the past, such programs typically required the work be completed within 90 days, but the deadline has been extended to six months for people who have already applied to remove their lawns and up to a year for new applicants.

Get paid to tear out your lawn

That means people can let their lawns die this summer, she said, and then start planting in the fall or winter, when cooler temperatures and (fingers crossed) seasonal rains make it easier for plants to settle into their new surroundings.

Most drought-tolerant plants, including California natives, do best when planted in fall and winter, when temperatures are cooler, but there are exceptions, said Tim Becker, horticulture director for the Theodore Payne Foundation. Some warm-season native grasses, such as blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), do best if they’re planted in the summer.

These grasses are “really, really drought-tolerant,” Becker said, and require little mowing, maybe two or three times a year, if people want to create a meadow area in their yards.

Becker recommends other native plants as lawn substitutes too, such as:

- Two varieties of sedge, sand dune sedge (Carex pansa) and clustered field sedge (Carex praegracilis), which use significantly less water than traditional lawns and don’t need mowing

- Bent grass (Agrostis pallens)

These grasses grow 6 to 12 inches tall and can be mowed infrequently to rejuvenate them, he said. But frequent mowing means they’ll need more water to fuel their regrowth, he said.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Under the rebate rules, synthetic turf is forbidden because the district is trying to promote surfaces that allow rainwater to permeate into the soil, according to the district’s website.

Traditional overhead sprinkling also will not be permitted, so your new plantings will have to be watered by hand or drip irrigation. That’s one of the reasons replacing a fescue lawn with a more drought-tolerant turf grass like Bermuda won’t qualify for the rebate, said Krista Guerrero, water efficiency specialist for the Metropolitan Water District. It’s also hard for inspectors to tell the difference between water-thirsty turf grasses and their more drought-tolerant cousins, she said.

Baird, the turf specialist, thinks that’s unfair. Many golf courses and commercial turf users have switched to Bermuda and other turf grasses bred to be more drought-resistant, and he thinks homeowners should be rewarded with rebates for doing the same. But Guerrero said the rebates are designed to encourage more water-efficient landscapes, and “even low-water-use turf grasses still use more water than other types of drought-tolerant plants.”

As Southern California’s drought conditions worsen, Los Angeles gardeners can keep their vegetables growing amid water restrictions with these tips.

Reduce the size of your lawn and focus water on the area you want to save

Consider a compromise. Mark out a green area where children and pets can play and then remove the rest of the grass to create planting areas for vegetables, fruit trees and drought-tolerant plants. (There are ways to efficiently water vegetables and trees during a drought.)

Native elderberry trees grow quickly, providing shade as well as food and shelter for birds and other creatures. A garden of drought-tolerant herbs, such as rosemary, oregano, marjoram and sage, adds color and fragrance to a sunny section of yard, as do lavender bushes and native plants such as Cleveland sage, matilija poppies, California buckwheat and hummingbird sage.

For inspiration, planning guides and resources check out:

- The California Native Plant Society’s Bloom California website and CalScape database.

- The Theodore Payne Foundation’s photos of its Native Plant Garden Tours, where at least 50% of the landscape must include California native plants.

- The Metropolitan Water District’s bewaterwise.com website, which includes planting guides for Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego and Ventura counties.

Help the trees in your yard by removing at least four feet of grass around their trunks. This will allow you to create a reservoir around the tree for deep watering once a week — running a hose on low for about 20 minutes — and provide an area to put a finely screened bark mulch to retain water. Just be sure to keep the mulch a good four inches from the tree trunk to reduce the risk of rot.

Drought-resistant plants like hummingbird sage and rosemary are the ideal addition to Southern California gardens.

If you try to keep your lawn, be prepared for a bleak summer

Baird believes every lawn owner should be reducing water use because of the drought, regardless of whether they live in water-restriction areas. He typically stops watering his Bermuda lawn between November and March (usually California’s rainy season) and then slowly begins watering one day a week and up to three days a week during the hottest months between July and September.

He’s been “deficit watering” this spring for just 16 minutes one day a week because the temperatures have been fairly cool, “and my lawn looks pretty rough,” he said. He couldn’t think of any type of grass that will look like you’re used to with watering just eight minutes a week. “It may not kill it all, but it’s going to look like it’s killed.”

Southern California officials have declared a water shortage emergency. Here’s how to keep gardening dreams alive while still restricting water use.

With that in mind, here are his tips for trying to keep your lawn at least somewhat alive under MWD’s water restrictions:

- Don’t wait until June 1 to switch to eight-minute-a-week watering, especially if you now water your lawn multiple times a week. Obviously your grass will go brown, but it could survive this stressful dormant period depending on how much it gets baked by the sun.

- Try adding a wetting agent this month, such as Scott’s Every Drop Water Maximizer, to improve water retention in the soil.

- If you want to fertilize, do it immediately and water it in well so your lawn will be less stressed going into its low-water period. If you try to add fertilizer a week before the water restrictions go into effect, you could be doing more harm than good. Nitrogen fertilizers, the only kind Baird recommends for a lawn, are a kind of salt and must be watered in well.

- Make sure the mower used on your lawn has sharp blades. Dull blades basically shred the grass, making it more vulnerable to water loss.

- If you live in a water-restriction area, stop mowing entirely after June 1. “Mowing will just stress it out even more,” Baird said. “As the grass starts to thin out, some weeds could pop up, but if you’re watering just eight minutes a week, there won’t be much growing.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.