Rodney King gets award of $3.8 million

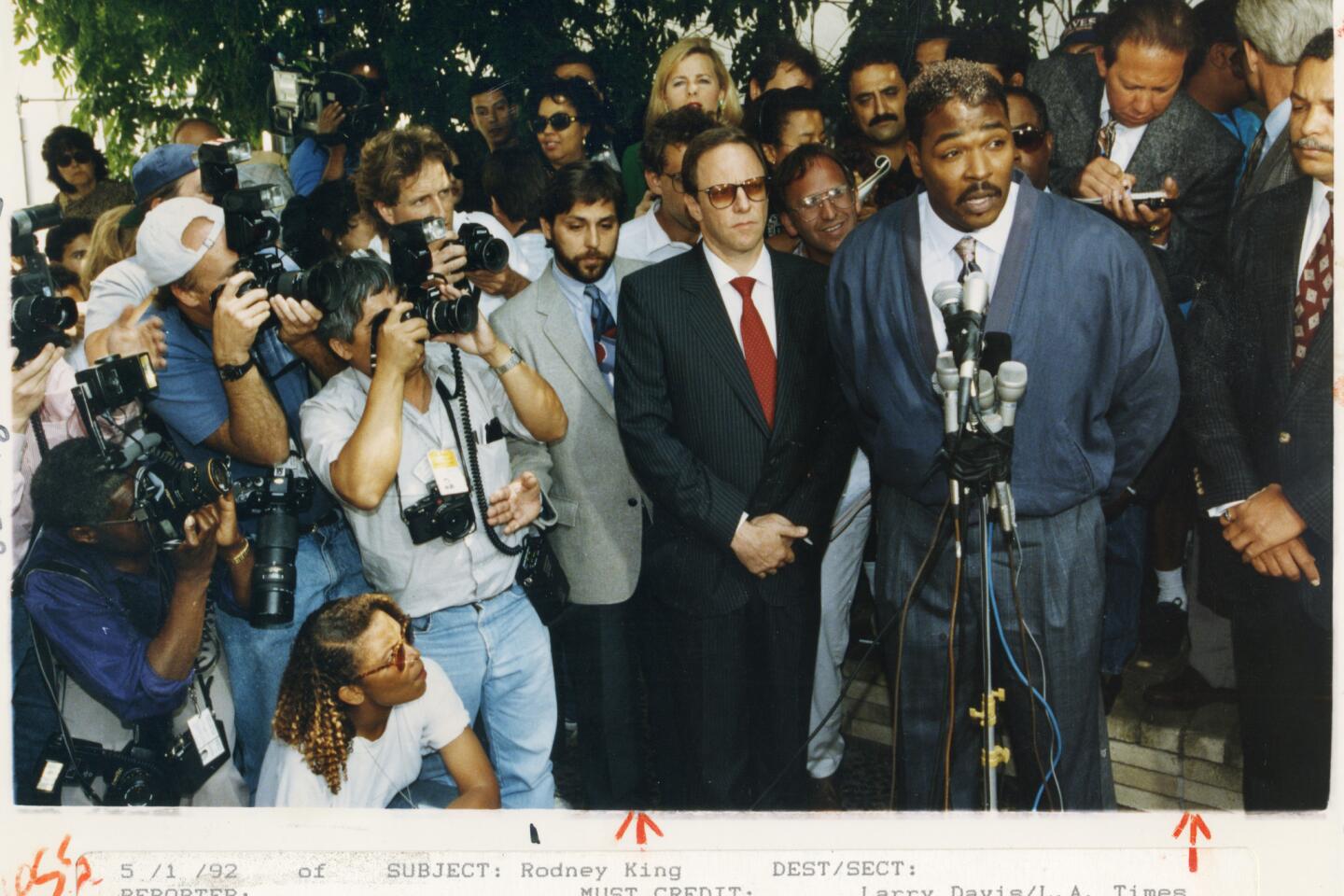

Steven Lerman, attorney for Rodney King, displays a photo of his client during a press conference at his office in Beverly Hills on March 8, 1991. King’s doctor outlined the extent of the man’s injuries for reporters during the meeting.

Three years after the 1991 beating that made him a national symbol of police brutality, Rodney G. King on Tuesday was awarded more than $3.8 million in damages from the city of Los Angeles.

The federal court jury award, which came on the fourth day of deliberations, was substantially less than the $15 million King’s lawyers had sought, but well above the $800,000 the city had offered initially.

“I was expecting, and I was hopeful, that Mr. King’s recovery would be greater than the $3.8 million,” said Milton Grimes, King’s attorney. “But I’m not dissatisfied.”

Mayor Richard Riordan had little comment about the amount, except to say that “the City Council will now review the jury’s award and study the city’s options.

“Now that (the jurors) have acted, we can hopefully put this chapter behind us,” Riordan added.

King was not in the courtroom for the reading of the verdict, although his lawyer said he was “somewhat pleased” with the award.

I felt like I had been raped. . . . I felt like a cow that was waiting to be slaughtered, just like a piece of meat.

— Rodney King

During the trial, King had graphically described the pain and humiliation he felt on the night he was beaten by Los Angeles police officers in the San Fernando Valley, telling jurors: “I felt like I had been raped. . . . I felt like a cow that was waiting to be slaughtered, just like a piece of meat.”

The compensatory damages awarded are intended to pay King’s medical expenses and lost income--for which only the city was held liable.

In the wake of the verdict, some questioned whether the award had been too large.

“I don’t think Rodney King’s injuries are worth $3.8 million. I don’t think Rodney King is worth $3.8 million in terms of his ability to make that much money in his lifetime,” said former Police Chief Daryl F. Gates, who resigned under pressure after 1992 riots that followed not guilty verdicts in the first trial of four officers accused in the beating.

Councilman Hal Bernson, who represents the San Fernando Valley, said: “Here’s somebody who was fleeing the law. . . . I wouldn’t have voted a nickel for him.”

But several council members said they doubt the city will appeal the case, and Councilman Zev Yaroslavsky, chairman of the City Council’s Finance and Revenue Committee, who two years ago blocked efforts to settle the case for $5.9 million, said he was frankly relieved that the jury had not been more generous.

“All in all, while I would have preferred a lower verdict, I think, to be candid with you, I was fearing a much higher verdict,” Yaroslavsky said. “Any time you go to a jury . . . you’re rolling the dice with the taxpayers’ money. We could never have settled this case at $3.8 million.”

Yaroslavsky said King’s attorneys had been unwilling to settle for that amount. But with court costs and punitive damages yet to be determined, the city could end up paying substantially more.

Meanwhile, legal scholars and civil rights advocates hailed the award--which for reasons that remain unclear was made in the exact amount of $3,816,535.45.

“I think it’s a verdict well within reason,” said Loyola University law professor and former federal prosecutor Laurie L. Levinson. “It sounds like what the jury did--because the number was down to the penny--was calculated very specifically (as) the actual damages suffered by King.”

Joseph Duff, president of the Los Angeles branch of the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People, added: “It shows the jury has rejected the argument that King is not permanently injured and accurately and compassionately reflects the pain and suffering from the beating itself.”

The awarding of the compensatory damages in King’s case ends the first of two phases of the civil trial. In the second, which will begin Thursday, the jury is to determine punitive damages and try to assign blame to individual defendants.

There is no way of knowing how much money--if any--the jury will award in this phase, which is aimed at punishing individuals who contributed to the violation of King’s civil rights.

Lawyers for King told U.S. District Judge John G. Davies that they plan to call 31 witnesses during the punitive damages phase, and defense attorneys estimate that they will put 45 people on the stand.

Fourteen individual defendants have been named, including Gates and the four former Los Angeles police officers originally charged in King’s case--Stacey C. Koon, Laurence M. Powell, Timothy E. Wind and Theodore J. Briseno. All are current or former city employees, and on Tuesday, City Council members expressed concern about whether taxpayers should pick up the tab if damages are assessed against the individual officers.

“Punitive damages may end up being substantial,” Councilman Nate Holden said. “I’m not prepared to say I’m going to cut a guy loose and let him lose everything. . . . As a practice, the city has always indemnified employees.”

However, Councilman Mark Ridley-Thomas said it would teach a lesson to rogue officers if the city forced them to take financial responsibility for their misdeeds.

Officers, he said, should “bear responsibility for their own behavior rather than passing it on against taxpayers.”

The civil trial is the third court proceeding since the March 3, 1991, beating was caught on videotape and broadcast on television, setting the stage for the worst urban riots in a century.

The first trial, a state criminal proceeding against the four officers charged in the case, ended with not guilty verdicts on all but one count--in which a mistrial was declared--in April, 1992. The verdicts, returned by a Simi Valley jury, touched off rioting that lasted three days and left at least 52 people dead in Los Angeles.

A year later, a federal civil rights trial of the same officers resulted in the convictions of two of them. Koon and Powell are serving 30-month sentences for violating King’s civil rights.

In 1994, for the third April in as many years, the case was before a jury again, with a new set of jurors asked to place a dollar value on King’s injuries, pain, suffering and loss of employment potential.

In closing arguments, his lawyers argued for the $15 million; the city argued that $800,000 was a fairer amount. But earlier, King had offered to settle for $9.6 million. Negotiations stalled after the city countered that offer with $1.25 million.

Throughout the three-week trial, the city has admitted liability, but its lawyers and medical experts sought to downplay King’s injuries and any permanent impairment or brain damage they might have caused. Meanwhile, the city emphasized King’s troubled past, eliciting testimony about a robbery conviction, his use of alcohol and drugs and his involvement with a transvestite prostitute.

King’s lawyers, meanwhile, portrayed him as the victim of a racist police force, a man who was brutally beaten for no reason other than that he was black. In fact, during King’s testimony--the most graphic account yet from the 29-year-old man--he told the jury that he could hear the police chanting racial epithets as they kicked him and struck him with their batons.

The question of whether racial epithets were uttered has been hotly disputed. Shortly after his arrest in 1991, King said he did not believe that the beating was racially motivated. Later, however, he said he had heard officers make racially derogatory remarks, and blamed his inconsistency on memory loss.

King testified that on the night of the beating, he had been celebrating with friends. Having been recently released from prison, where he had served time for robbery, King said he was feeling proud that night because he had managed to win back his job with a construction company.

But he had too much to drink, he told the jury, and when he saw police in his rearview mirror, he panicked. He was afraid, he said, that he would be sent back to prison and decided to make a run for it.

Although police had testified that King led officers on a long, high-speed car chase, King said that he tried to elude officers only for about 12 blocks before deciding it made little sense to run.

King said that after stopping, he did not resist and tried to comply with officers’ commands, adding that he did not strike out or attack the officers who beat him, acting only in self-defense.

Eventually, he said, he followed orders to lie down on the pavement, but when he did, an officer struck him with his baton.

“I felt like I had lost half my face,” he said, but he told the officer that he “felt fine” because he “didn’t want to give him the satisfaction of knowing that it really hurt.”

The beating--which police defended by noting that, in their eyes, King was a violent, defiant suspect who had not been searched for a weapon--was captured on videotape by a resident of an apartment building across the street.

Excerpts were aired around the world, serving as a flash point for racial tensions as the grainy image of the cowering King was shown to billions of viewers.

“I could hear my bones crunching every time the baton hit me,” King testified. “It sounded like throwing an egg and hearing the shell crack. . . . I was just so scared. I felt like I was going to die.”

King’s medical experts said his injuries have left him with permanent brain damage, chronic headaches and an inability to focus his thoughts or concentrate. Meanwhile, his lawyers said, his notoriety has made him fearful and so paranoid that he wears a bulletproof vest on the rare occasions when he ventures out in public.

It is unclear how much of the jury award King will end up keeping. Although he is expected to retain the bulk of the money, one of his former lawyers, Steven Lerman, has a lien against his judgment for $780,000 worth of unpaid legal services.

Moreover, King has nine attorneys on his current legal team, none of whom have been paid. Grimes, who took over the case when Lerman was fired in 1992, also has been lending King an estimated $5,000 to $10,000 a month to help him meet his living expenses during the court proceedings. King will almost certainly be expected to repay those expenses from his award.

The legal fees, however, will not necessarily come out of King’s pocket. In police brutality cases, attorneys may apply to the judge at the trial’s end to have defendants pay fees and court costs. That means the city of Los Angeles may eventually have to pay King’s lawyers, in addition to King.

Times staff writers Bettina Boxall, Edward J. Boyer, Richard Simon and John Hurst contributed to this story.

City Settlements

Here is a list of settlements and jury awards of $1 million or more paid by the city of Los Angeles in police-related legal cases from fiscal year 1988-89 to December, 1993:

* PLAINTIFF: Benny Powell and Clarence Chance

Case: They were imprisoned for a murder they did not commit.

Outcome: Settled for $7 million ($3.5 million each).

* PLAINTIFF: Alicia Diaz

Case: Diaz’s teen-age daughter was molested by an officer at her parents’ home in 1989.

Outcome: $6.3 million awarded; the convicted officer was ordered to pay an additional $3.1 million in punitive damages.

* PLAINTIFF: Adelaido Altamirano

Case: The Coliseum groundskeeper was shot by an off-duty officer and left paralyzed in 1987.

Outcome: Settled for $5.5 million.

* PLAINTIFF: Onie Palmer

Case: Home was damaged during drug raids on Dalton Avenue in 1988.

Outcome: Settled for $3.2 million.

* PLAINTIFF: Service Employees International

Case: A confrontation among union janitors, the national union and police in Century City in 1990.

Outcome: Settled for $2.35 million.

* PLAINTIFF: Murphy and Katie Pierson

Case: Wrongful shooting by police officers in 1985.

Outcome: Settled for $1.8 million.

* PLAINTIFF: James Thomas Mincey Jr.

Case: Mincey died after a chokehold was applied by police after his arrest in 1982.

Outcome: Settled for $1.6 million.

* PLAINTIFF: Gilbert Amescua

Case: Injured in a suicide attempt while in custody in 1987.

Outcome: Settled for $1.5 million.

* PLAINTIFF: Ronnie Melgar

Case: Burglary suspect suffered brain damage after being shot while fleeing police in 1981.

Outcome: Settled for $1.45 million.

* PLAINTIFF: Erik Davis

Case: Suspected car stripper was shot by police in 1990.

Outcome: Settled for $1.4 million.

* PLAINTIFF: Ardeshir Asgari

Case: Suspect spent seven months in jail in 1987 after being wrongly arrested by a narcotics officer.

Outcome: $1.3 million awarded.

* PLAINTIFF: John L. Daniels Jr.

Case: The tow-truck driver was fatally shot by an officer while trying to drive away from a service station in 1992.

Outcome: Settled for $1.2 million.

* PLAINTIFF: George Carpenter

Case: Theater manager was critically shot in 1985. Police had learned about a threat to kill him but never warned him.

Outcome: Settled for $1.2 million.

* PLAINTIFF: Tracy Mayberry

Case: Suspect hogtied by police died in 1990.

Outcome: Settled for $700,000.

Source: City attorney’s office

Compiled by CECILIA RASMUSSEN / Los Angeles Times

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.